Queensland University of Technology Law and Justice Journal

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

Queensland University of Technology Law and Justice Journal |

|

Chris

Geller[*]

A

number of theories seek to explain how increases in women’s participation

in job markets relate to decreases in women’s

wages.[1] While not contesting the

general observation that as more women enter an employment field, wages tend to

decrease in that field,

this paper addresses a rather more restricted result. A

decrease in relative wages can lead to women entering a field. Certainly,

women

are not attracted to low salaries per se. Rather, as a salary is

suppressed below market rates, employers in that field must increase other

benefits in order to maintain

their employment

levels.[2] It is possible that these

increased benefits may be relatively more attractive to women than to men. I

propose that Australian

academia, especially in the areas with a high paid

professional private sector, is just such a case. I look specifically at law,

and ask the question: Is this a problem, or an opportunity? Should this

phenomenon be opposed or used?

A university

administrator[3] recently noted to me

that the professoriate in my faculty will become more balanced by gender because

men want higher pay and women

appreciate the hours. When pressed, she explained

that although there is pressure for increased “efficiency” and

regular

hours, she does not think that movement will succeed. Likewise, while

I was calling universities to get general information about

academic law in

Australia, a head of school discussed this topic with me. He thought that

academic law should particularly suit

women with small children: “If there

is no baby sitter, stay home”. He expressed three concerns with

employees: publications,

teaching quality, and availability to students. Given

the state of electronic communication, he considered availability to be easily

maintained. Thus, academic faculty should be able to function from home if they

wished. He claimed to have no interest in controlling

academic staff

members’ time, although one would suspect that he would like the school to

have significant input in scheduling

of units. He did acknowledge that certain

of his superiors do want academic staff to be on campus for regular work

hours.[4]

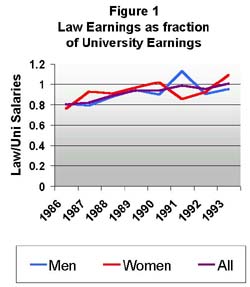

Academic salaries have not risen as much as legal salaries recently. For

example, consider the years between 1986 and 1993, the most

recent years with

consistent data available. In 1986 lawyers earned an average of about 80

percent of average academic salaries.

By 1993, law salaries had risen to equal

academic salaries.[5] See figure 1.

During the 1990s the government tightened university funding and loosened

regulations on the private sector, therefore

it is likely that this trend

continued in kind if not degree.

Becker contrasted her experience practicing law and serving as an

associate dean with “being a regular faculty

member”.[6] While her

observations are not quantified, they are convincing. Three of her comparisons

are particularly telling on the issue

of working hours. In administration and

practice she “had to keep track of vacation and sick days”,

“worked a

good portion of most weekends” and “had to be

physically present at work many more hours than any brand of pantyhose

would

comfortably accommodate.”

Few Australian women professionals in

private legal practice take their full entitlement of parental leave due to

pressure to maintain

their careers.[7]

Hunter and McKelvie document that barristers face particular constraints imposed

by court schedules, solicitor contracts, and the

premium placed on continuous

practice. These constraints limit barristers’ ability to adjust work

schedules around other needs.[8]

Personally, my wife and I have found it much easier to adjust academic schedules

around child rearing needs than to adjust law practice

schedules.

Universities and academic staff both care about wages and staff control

of work schedules. Of course, they do not precisely agree.

Universities would

prefer to pay lower salaries for any given quality of employee, and to have more

control over work schedules.

Staff members desire the opposite: higher wages

and more staff control over their work schedules (flexibility). In large, free

and well-informed markets, employers and employees find a mutually agreeable

(tolerable) balance. In this balance, both employees

and employers

“trade” lower wages for more flexibility and vice versa. In

this trade-off, women tend to emphasise control over work schedules more than do

men.[9] There are many biological,

cultural, and social reasons for this difference. These reasons centre on, but

are not limited to, caring

for young

children.[10] For example, part-time

solicitors in large Australian law firms were primarily women with young

children.[11]

Consider a

colleague’s experience in her first private practice position. Katherine

(not her real name) was called for an interview

with a small but high-pressure

litigation practice. She wanted to work for this firm, but did not want to work

the normal 70 to

80 hours per week. In her second interview she proposed a

billable hours target of 1800 hours per year and a salary 20 percent lower

than

advertised. They accepted her reduction in hours – although they

subsequently still tried to get her to work more hours

– and rather than

reducing her salary, they acknowledged that she was not on a track for

partnership until she removed her

hours cap.

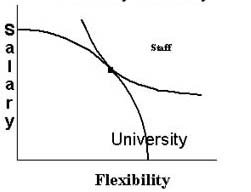

One way to organise this

information about willingness to trade salary for control over work-times is to

draw it in a diagram. Consider

figure 2. The curve labelled

“University” shows all the combinations of salary and control over

staff work-times that

the university’s representatives consider equally

satisfactory. The curve labelled “Staff” indicates all the

combinations

of salary and work-time control that a standardised staff member

would consider equally satisfactory. Since equally satisfactory

points are

linked, these are called indifference curves (IC).

The indifference

curve for the university slopes down to the right indicating that the university

would be willing to surrender control

over time to academic staff – a

movement to the right – if there is also a decrease in wage – a

movement downward.

As staff control over time increases, the slope of the curve

increases. This shows that when academic staff have high levels of

flexibility,

the university would be increasingly unwilling to give yet more control to the

staff. Likewise, when the university

already has considerable control over

staff time (areas on the left of the diagram) the university would concede some

flexibility

for relatively small reductions in wage.

The staff members

would also be indifferent to a loss of control over work-time only if it came

with an increase in salary. Thus,

the indifference curve for the staff members

also slopes downward to the right. However, unlike the university, at lower

levels

of staff control of work-time, staff members would require greater

increases in compensation to remain indifferent to further reductions

in control

over their time. Expressed differently, when the employer controls work-times

closely, a bit of freedom is very valuable

(steep slope) to the employee.

Conversely, when employees can work whenever they like, being able to at least

set one meeting time

and require everyone to be there may be very valuable

(steep slope) to an employer.

These diagrams also illustrate an

additional element of choice. Staff members do not take jobs below and to the

left of the indifference

curves because of alternate opportunities. The

placement of the curves shows, in effect, the next best job available to the

potential

employee.[12] A job to the

lower left has lower pay and less work-time autonomy. We will refer to

the employee’s curves as indifference/offer curves (IOCs).

In

this simplified diagram, all staff members have the same preferences and the

university acts as a unified whole. Allowing preferences

to differ between

individuals and within the university makes the diagram fuzzy, but does not

substantially change the results.

There are a few other core assumptions that

drive this diagram, and they are worth reviewing explicitly. First,

universities desire

lower salaries for academic staff and desire higher levels

of control over work schedules. Second, as university control over staff

members’ time decreases, the remaining control is increasingly valuable to

the university. Third, academic staff prefer higher

wages and more autonomy

over their time. Fourth, as staff members’ control over their time

decreases, the remaining control

is increasingly valuable to the staff members.

Fifth, potential staff members are informed about alternative employment. The

diagram

is useful and relevant only to the degree that these assumptions apply

to any given situation.

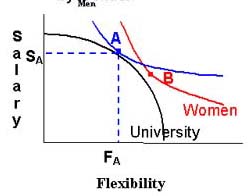

The diagram can be modified to illustrate gender

differences in values of control over work-times. A steeper slope means a

higher

value of control over work-time. That is, a steeper slope means that a

greater increase in salary would be required to compensate

for lost work

flexibility. Now suppose we add a sixth assumption that women value flexibility

more than men do. Therefore, women’s

indifference curves are steeper than

men’s at all levels of control over work-times. See figure 3.

This figure shows an industry with predominantly male employment. By

altering the employer’s preferences (lower and wider IC)

we can easily

illustrate an industry with predominantly female

employment.[13] In figure 3, the

university can reach the men’s IOC with the relatively high wage and low

flexibility point A (flexibility

of FA, salary of SA).

In order for the university to hire women, given their preferences for

time-control and wages, the university would have to provide

a package at point

B. Since B lies outside of the IC with A, the university prefers A. Given this

configuration of preferences,

academic staff would be predominantly

men.

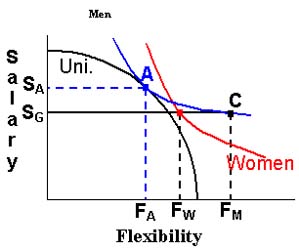

The results change dramatically when a wage lower than SA

is imposed on the university. See figure 4. Suppose that the government

imposes wage SG on the universities, possibly through low funding.

In order to hire men at the imposed wage, universities would have to reach point

C, providing flexibility at FM. Counter-intuitively, women are

willing to work at a lower level of flexibility FW than are men at

this low wage. The deeper intuition behind this is that men do not value

additional flexibility much at high levels,

and so must receive large amounts of

it to be indifferent to a wage reduction. The result is that the university

provides the imposed

wage and flexibility at FW, and university

employment becomes increasingly feminine.

If one accepts the assumptions

behind the diagrams, then one should consider that it is likely that lowered

salaries are a force for

feminisation of the legal academic workplace. Further,

this force is not simply that men have surrendered the field, leaving it

to be

passively filled by women, as Strober’s relative attractiveness theory

would have it.[14] Rather, women and

men both compare salary to flexibility, and feminization occurs through a

comparative

attractiveness.[15] In this

comparative attractiveness, both genders compare the attractiveness of various

goods (flexibility and salary). However,

the comparative attractiveness concept

does not imply that women are on an equal footing with men in labour markets.

The comparative

attractiveness of flexibility and salary across genders is built

upon alternatives in employment and considerations of family care.

Each of

these foundations may arise from external constraints imposed upon women. What

comparative attractiveness contributes is

a suggestion of potential opportunity,

placed on equal footing with disadvantage in the labour sector.

Although realistic assumptions and direct logic yield an interesting

result, it is expedient to check observations. Gender distributions

in

employment between associate lecturer, lecturer, and senior lecturer in

Australian Schools of Law are consistent with the theoretical

result above. If

women are entering law more now than in the recent past, one would expect

relatively more men among senior lecturers

and relatively more women among at

entry level, either associate lecturer or lecturer. Twenty Australian Schools

of Law identify

their staff by academic rank on their web-sites and gender can

be identified for nearly all of these academicians by personal name

or

photographs. Seventeen of these 20 law schools indeed have relatively more

women in the junior ranks than at senior

lecturer.[16] This result is

consistent with the theory developed above. However, other factors such as

discrimination could also lead the same

observation. A more complete empirical

analysis would require data on experience, publications, teaching, service, and

other work

related characteristics for academicians in law. Yet even with more

thorough data and analysis, discrimination could not be precluded

as a cause for

women constituting relatively more of junior staff. Currently, the author is

content that real world observations

do not contradict expectations and that

colleagues recognise that the forces described here fit their experiences and

their observations

of their universities. Since theory, personal experiences,

and observations match well, perhaps the next step should not be detailed

statistical analysis of the obvious, but rather a political decision.

What should be done? Is this feminisation that is driven by low relative

wages a problem to solve or an opportunity to grasp? Should

this author be part

of the process of these decisions and actions, or should he go on to other

theoretical work and request to be

informed about developments? Please E-mail

your thoughts and word of any actions to

cgeller@deakin.edu.au.

Figure 1

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics, Distribution and Composition of

Employee Earnings and Hours—Australia (various years).

Figure 2

Willingness to Trade Flexibility for Salary

Figure 3

Willingness to Trade Flexibility for Salary

by

Gender

Figure 4

Flexibility and Fixed Salary

by Gender

[*] School of Economics, Faculty of Business and Law, Deakin University. I appreciate comments by K Lee Adams, participants at F-Law 2001 (Feminist Legal Academic Workshop) Brisbane, 14-16 February 2001 and an anonymous reviewer.

[1] O Ashenfelter and T Hannan,

‘Sex discrimination and product market competition: the case of the

banking industry’ (1986) 101 Quarterly Journal of Economics

149-173. K Bayard, ‘New evidence of sex segregation and sex differences

in wages from matched employee-employer data’ (1998)

University of

Michigan Econometrics and Economic Theory Paper No 9801. M Carter and S Boslego

Carter, ‘Women’s recent

progress in the professions or, women get a

ticket to ride after the gravy train has left the station’ (1981) 7

Feminist Studies 476-504. D MacPherson and B Hirsch, ‘Wages and

gender composition: Why do women’s jobs pay less?’ (1995) 13

Journal of Labor Economics 426-471. B Reskin and P Roos, Job Queues,

Gender Queues, Explaining Women’s Inroads into Male Occupations 1990.

E Sorensen, ‘Measuring the effect of occupational sex and race composition

on earnings,’ in R T Michael, H I Hartmenn

and B O’Farrell (eds)

Pay Equity: Empirical Inquiries 1989.

[2] Two key assumptions underlie

this conclusion. First, previous wage rates were balanced relative to other

markets and non-wage working

conditions. Second, individuals may enter or leave

the field of employment. Note that the time for entrance and exit would

contribute

to the length of time taken to adjust other

benefits.

[3] Individuals will

remain unidentified beyond role and

gender.

[4] Rather than actually

increasing flexibility, universities may lag behind the private sector in a

broad drive toward greater employer

control. This position presented in this

paper addresses the difference in flexibility between universities and the

private sector,

rather than absolute levels of

flexibility.

[5] Australian Bureau

of Statistics, Distribution and Composition of Employee Earnings and

Hours—Australia (various

years).

[6] S Becker,

‘Thanks, But I’m Just Looking: Or, Why I Don’t Want to Be a

Dean’ (1999) 49 Journal of Legal Education

595.

[7] C Sherry,

‘Parenting and the legal profession’ [1999] LawIJV 26; (1999) 73 Law Institute

Journal 58-59.

[8] R Hunter

and H McKelvie, ‘Balancing Work and Family Responsibilities at the

Bar’ (1999) 12 Australian Journal of Labour Law 167-192.

[9] K Arnold, Lives of Promise; What Becomes of High School Valedictorians: A Fourteen-year Study of Achievement and Life Choices 1995. R Easterlin, ‘Preferences and prices in choice of career, the switch to business, 1972-87’ (1995) 27 Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 1-34. ‘Why women managers are bailing out’ Fortune August 18, 1986, 16-23.

[10] See for example M Thornton,

Dissonance and Distrust: Women and the Legal Profession 1996,

139-165.

[11] M Martin,

‘Working nine to five: Not a way to make a living if you’re bringing

up young children’ (1992) 66 Law Institute Journal

286-287.

[12] This diagram can

thus also show the impact to employment from changes in discrimination,

technology, etc in the economy as a

whole.

[13] It may be

interesting to note that gender-balanced results are much more restricted in

their configuration.

[14] M

Strober, ‘The relative attractiveness theory of gender segregation: the

case of physicians’ (1992) Proceedings of the 44th Annual

Meetings of the Industrial and Labor Relations Association at 42-50.

[15] This is a parallel to

comparative advantage, which compares two producers’ trade-off between

producing two goods. Although

I do not know of “comparative

attractiveness” being used before, the close parallel comparative

advantage makes it unlikely

that the former was coined

here.

[16] Documented using

links from Macquarie University’s fine central resource Jurist Australia

at

<http://jurist.law.mq.edu.au/lawschl.htm>

on 21 and 22 July 2001.

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/QUTLawJJl/2001/16.html