Melbourne University Law Review

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

Melbourne University Law Review |

|

TERRY HUTCHINSON[*]

[This article explores the development of tertiary legal research skills education in Australia in the underlying context of Australian legal education and the transformation of legal research resulting from advances in information technology. It argues that legal research is a fundamental skill for lawyers and that research training in a law degree must cater for the vocational needs of the individual student whether their ultimate focus is practice or higher degree research. It argues that the traditional doctrinal paradigm of legal research is no longer sufficient for modern lawyers and that exposure to additional methodologies needs to be included in research training units. This article argues that while legal research skills education has changed, it must continue to develop in order to better cater for the needs of students, the profession and the academy in the contemporary legal environment.]

CONTENTS

Legal research skills training in Australia has undergone a revolution in the last two decades. A research paradigm shift has occurred, driven by the communications technology revolution, economic globalisation and corresponding changes within tertiary education, the legal profession and the legal education sector. These changes have prompted self‑questioning within the legal academy about the nature of legal education, the nature of legal research and the methodologies involved. The questions have revolved around two issues: ‘what is the nature and meaning of “legal research”?’ and ‘how is research training best achieved?’. In turn, these two very simple issues have prompted other questions such as ‘what methodologies are most effective in achieving the aims of legal research?’[1]

Because the legal research agenda in universities has historically been practitioner‑driven, the nature of legal research has been defined narrowly and largely confined to doctrinal research.[2] This typifies the legal practitioner model of research. However, legal research encompasses a wider concept than mere doctrinal research skills, especially if a legal academic scholarship model rather than a legal practitioner model is considered. Lawyers have tended to conflate the doctrinal methodology with the overarching paradigm, demonstrated both in praxis and in the dialogues on the issue.[3]

Consequently, legal research has been perceived as being limited to doctrinal research. The prevailing assumption has been that undergraduate and postgraduate students do not need much research training beyond a basic introduction to legal sources. This assumption arises from a belief that research is so intrinsic to the underlying legal doctrinal paradigm practiced by all lawyers that the skills would be picked up by a process akin to osmosis.[4] This approach to teaching legal research skills lacked explication and clarity. Explicit research training is required and the optimum way to accomplish this is through gradual layers of training directed towards specific student needs.

This article begins with a historical examination of legal research in Australia and highlights the main features of the changing environment affecting legal research. Major changes in the last two decades have forced dynamic shifts. These changes include the pervasive power of information technology, the re‑examination of research imperatives in the tertiary sector prompted by Australian government funding policies, the impetus to improve university teaching through acknowledgement of educational theory, and the increasing trade in professional legal services which is paving the way for the emergence of the transnational lawyer. Legal research skills have always been considered to be important for both academic and practising lawyers.[5] These new forces are encouraging a changed legal research paradigm and emphasising the need for enhanced research training in the law curriculum.

These major contextual forces make it imperative that there be a transformation in legal research training. In the present day, there must be an emphasis on research process rather than simply a study of research sources, the use of a broader range of research methodologies apart from a simple doctrinal approach and the integration of research and writing processes so that writing genres become a part of the research curriculum. More recognition needs to be given to the benefits of a ‘point of need’ approach to research training, and also to the various vocational outcomes of research training for both legal academic scholarship and legal practice.

Historically, the legal profession in Australia comprised either of those admitted to the legal profession in the United Kingdom, or those who had ‘passed examinations conducted by professional training authorities and (in the case of solicitors) undertaken articles in Australia.’[6] The change to university‑based education for lawyers gradually encouraged the growth of a class of full‑time legal academics who had more time and opportunity to pursue research interests.

Academics in the United States and Canada had already begun exploring the definitions, quality, nature and role of legal research, and the steps necessary to encourage legal research in the 1950s. However, it was not until the Australian Law Schools: A Discipline Assessment for the Commonwealth Tertiary Education Commission report (‘Pearce Report’) in 1987 that any formal public consideration was given to defining legal research in Australia.[7] The Pearce Committee adopted the Australian Law Deans’ definition of research as encompassing:

1 doctrinal research — ‘research which provides a systematic exposition of the rules governing a particular legal category, analyses the relationship between rules, explains areas of difficulty and, perhaps, predicts future developments’;

2 reform‑oriented research — ‘research which intensively evaluates the adequacy of existing rules and which recommends changes to any rules found wanting’; and

3 theoretical research — ‘research which fosters a more complete understanding of the conceptual bases of legal principles and of the combined effects of a range of rules and procedures that touch on a particular area of activity’.[8]

The Law and Learning: Report to the Social Sciences and the Humanities Research Council of Canada by the Consultative Group on Research and Education in Law (‘Arthurs Report’) — an earlier 1982 landmark study on the state of legal research and scholarship in Canada — had included a fourth category, but this was missing from the Pearce Report description. This other category, ‘fundamental research’, covers the study of law as a social phenomenon:

fundamental Research — research designed to secure a deeper understanding of law as a social phenomenon, including research on the historical, philosophical, linguistic, economic, social or political implications of law.[9]

This very important category had received more attention from the Arthurs Report in Canada than the Pearce Report in Australia and it is this category which is becoming more prevalent in current research agendas. It encourages an interdisciplinary perspective and the use of methodologies borrowed from the social sciences to study the law in operation.

In the late 1990s, the Australian Standard Research Classification (‘ASRC’)[10] scheme began to be used to classify research undertaken in Australia in order to enhance statistical data collection on research and development. This statistical data was stratified according to type of activity, research fields, courses and disciplines, and socioeconomic objectives. These types of activity were reflected in the Australian Research Council’s (‘ARC’) definitions including:

• pure basic research, being experimental or theoretical work undertaken primarily to acquire new knowledge without a specific application in view. It is carried out without looking for long‑term economic or social benefits other than the advancement of knowledge and includes most humanities research;

• strategic basic research, being experimental or theoretical work undertaken primarily to acquire new knowledge without a specific application in view, and is directed into specific broad areas in the expectation of useful discoveries. It provides the broad base of knowledge necessary for the solution of recognised practical problems;

• applied research, being original work undertaken to acquire new knowledge with a specific practical application in view. Its aim is to determine possible uses for the findings of basic research or to determine new methods or ways of achieving some specific and pre‑determined objective;

• experimental development, being systematic work, using existing knowledge gained from research and/or practical experience, for creating new or improved materials, products, devices, processes or services. In the social sciences, experimental development may be defined as the process of transferring knowledge gained through research into operational programs.[11]

The Pearce Committee’s theoretical research category would mainly be included in the ‘pure basic’ category. Most legal research has traditionally been directed towards legal practice and has thus tended to fall into the third category of ‘applied research’.

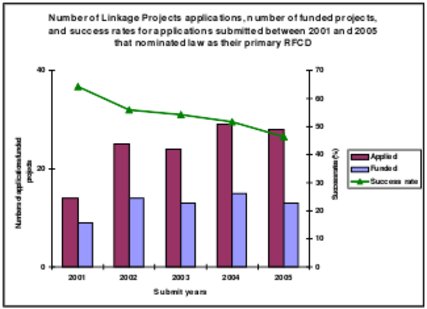

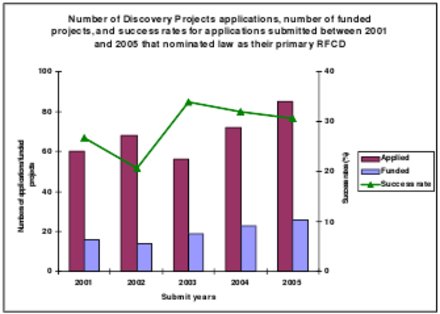

This emphasis on applied legal research aligns well with the current governmental focus on practical outcomes and the popularity of publicly funded ARC Linkage Grants which encourage academic researchers to join with private industry in pursuing mutually beneficial projects. An examination of ARC Linkage Grants Projects submitted from 2001–05 that stipulated law as their primary area shows an increasing number of applications. The actual application numbers dropped in 2007 and only seven were funded. This was the lowest result since the inception of the National Competitive Grants Program. The numbers of ARC Discovery Grants applications for law are higher overall. There were 73 in 2007. However, only 15 were funded.[12] The National Program has funded approximately 11 157 projects from all disciplines in the period between 2002 and 2008 (not including the new projects announced recently for funding commencing in 2009).[13] These figures demonstrate the importance of research training, and also suggest that enhanced research methodologies training may be required for legal researchers.

Figure 1: Number of Linkage Projects Applications, Number of Funded Projects and Success Rates for Applications Submitted between 2001 and 2005 That Nominated Law as Their Primary RFCD

Figure 2: Number of Discovery Projects Applications, Number of Funded Projects and Success Rates for Applications Submitted between 2001 and

2005 That Nominated Law as Their Primary RFCD[14]

The Australian government is intensely interested in the quality of research. In 2005, the release of the issues paper Research Quality Framework: Assessing the Quality and Impact of Research in Australia (‘RQF Paper’) led to further questioning of the way lawyers research.[15] The paper raised two main points — how the quality and impact of research should be recognised and measured, and who should assess the quality and impact of research in Australia.[16] The new federal government elected in November 2007 put an end to this project. The Minister for Innovation, Industry, Science and Research, Kim Carr, announced a new system — the Excellence for Research in Australia (‘ERA’) scheme.[17] In addition, the Minister for Education Julia Gillard announced a review of higher education to be conducted by Professor Denise Bradley.[18] The House of Representatives Standing Committee on Industry, Science and Innovation is currently conducting public hearings across Australia as part of its inquiry into research training and research workforce issues in universities,[19] and Dr Terry Cutler is chairing a Panel on the Review of the National Innovation System.[20] These developments, the impetus towards competitive research grants, an environment directed towards ensuring research quality and a renewed interest in research training have prompted a number of questions directly affecting law faculty funding, legal scholarship and legal research training. These questions include:

• what is the nature and meaning of ‘legal research’?

• what is ‘different’ about how lawyers research?

The underlying purpose of processes such as the Research Quality Framework (‘RQF’) and the ERA is to identify excellence in and create incentives for quality research.[21] If legal researchers cannot establish quality and impact factors as successfully as those from other disciplines, then public funds are less likely to be directed towards their projects.

In their submission in response to the RQF Paper, the Council of Australian Law Deans (‘CALD’) tried to address some of the basic definitional issues raised in the earlier research reports and still considered fundamental to the main arguments. They stipulated that:

The breadth of the idea of fundamental legal research illustrates the point about overlapping categories. Legal research today may be thought to be considerably broader than the tripartite classification of the Pearce Report, as it embraces empirical research (resonating with the social sciences), historical research (resonating with the humanities), comparative research (permeating all categories), research into the institutions and processes of the law, and interdisciplinary research (especially, though by no means exclusively, research into law and society). The Pearce Report did not really capture these extended elements of legal research, yet in some ways they are not so much new categories as new or newly‑emphasised perspectives or methodologies. They highlight law as an intellectual endeavour rather than as a professional pursuit, though the latter is undoubtedly enriched by the former.[22]

The submission attempted to delineate the existing categories of legal research but admitted that this was too difficult: ‘the flavour of the richness and diversity of legal research in Australia today may best be sampled by actually perusing collected outputs.’[23]

Government examination of higher education and research agendas continues and in this process the recognition of the panorama of legal research has extended significantly since the Pearce Report. When published legal research is reviewed, there are definitely signs of change and it seems clear that the law is beginning to escape from the confines of old doctrinal paradigms, but at varying rates throughout the sector. It is not one holistic methodology, but rather a range of methodologies — many of which have been borrowed from the social sciences — which are being combined to provide a more complete answer to research questions. There are signs that, on the whole, legal research is becoming more complex and sophisticated in its approach to investigating answers to issues that confront citizens today. Legal research and scholarship therefore must not only be viewed through the prism of history, but also of its modern context. However, this conclusion then raises the question as to how this changed context is affecting skills training in legal research.

This Part will describe some recent developments which have prompted a change in emphasis for research skills training. It demonstrates how the Australian legal research context in 2008 is entirely different from that of 20 years ago. Technology has been a dominant factor in the change. It has revolutionised communications. It has broadened research markets and research audiences and potential research impacts. Australian government funding policies for research have prompted the universities to re‑examine how they approach research and research training. Tertiary education theory has underscored the importance of teaching and active learning, and the old source‑based training programs have been largely discarded in favour of ones using more educationally sound techniques. Economic globalisation and trade agreements in services have opened up new markets and forced competition and rationalisation. Increasingly, these are leading to a new breed of ‘transnational’ lawyer. All these changes have impacted upon legal scholarship and practice and are revolutionising legal research.

Lawyers in the 19th and 20th centuries were avid users of printing and publishing communication technologies. Case decisions and reports were printed and stored, forming the basis of legal precedents and the common law. As the amount of material became too unwieldy, editors decided which cases were most important and of lasting value, measured by the principles they espoused, the calibre of the judicial reasoning demonstrated and the skills of the reporting. Legal digests were compiled providing indexed materials summarised under the main legal principles in order to simplify access to the wealth of information. Intricate systems of cross‑referencing helped users access peripheral material and delve deeper into their subjects.[24]

Due to the pervasive importance of the common law and precedent in the Australian legal system, publishing houses in the 20th century thus sought ways to track case law and legislation so as to enable lawyers to use the primary materials of the law most effectively. The published reference tools they produced aspired to be authoritative, well‑indexed and updated with reasonable frequency. These tools included primary materials — legislation, law reports, and relevant parliamentary or extrinsic materials — accompanied by indexes and digests of case law. Annotations of legislation which linked relevant case law were also added. Another layer of reference aid were case citators providing information on judicial consideration of important decisions, and a very limited range of journal indexes and legal encyclopedias were available. Gradually looseleaf services provided faster access to the cases and legislative changes as well as some more commentary. These tools were not easy to use, often because they had been organised by editors and publishers rather than lawyers. Librarians were often the main users, and lawyers needed to be trained in how to use their tools of trade in order to enable them to update and find the law.

Given lawyers’ history of using printing press technology and their need for data access, it is not surprising that they were quick to adopt newer technology. Legal data was ripe for transfer to full text databases, and information technology solved a problem for lawyers by making the sources easier to access and use. LexisNexis, a large US‑based company, was quick to recognise this potential and created an online electronic database which allowed lawyers to use research systems themselves, rather than depend on an intermediary such as a law librarian. The adoption of that system by the profession in Australia was hampered by the cost of the US service along with the paucity of local material being offered on the US system. However, Australian governments, universities and the main publishers all worked towards making current legislation and case law available electronically.[25]

There is now more information being generated, of which more is being made publicly accessible in electronic form: databases of secondary sources and journal indexes — such as the Attorney-General’s Information Service (‘AGIS’) — converted from their print equivalents; collection of court judgments at all levels; and increasing electronic access to new Acts and amendments, with reprints of amended legislation also becoming available in a timely fashion. At first, data sets of material which had previously been available only in hard copy were uploaded. Gradually, the publishers worked to transmute the datasets into new electronic products. For example, FirstPoint is a database which includes the Australian Digest and the Australian Case Citator, as well as basic hard copy sources in the old environment. It is an example of this new generation of offerings which will gradually replace the old ‘print clone’ datasets.

The internet makes a broader range of legal materials — including international and comparative law — available for searching and browsing. Parliamentary information and debates, government department websites, and updated legislation and commentary are all freely and easily accessible. While providing free access to a wealth of information, the internet also removes the assurance of quality provided by the publishers’ editorial control. This therefore requires users to be skilled in critique in order to deal with the sites they are using.[26]

These new research technologies pose challenges for the research curriculum and have several consequences for research training. In particular, there is a greater need for training in effective reading, critique, analysis and electronic searching skills. Research training needs to promote independent research skills so that graduates are able to work in dynamic web‑based legal environments. In addition, graduates need a thorough grounding in research ethics especially with regard to plagiarism and the ethical use of research sources.

Technology has directly affected training methods. Our Universities: Backing Australia’s Future, the 2003 report on tertiary education by former federal Minister for Education, Brendan Nelson, underlined the importance of information technology in establishing global networks for research and education.[27] E‑learning has affected the traditional lecture, tutorial and seminar system of teaching. Online teaching sites allow students to access basic course outlines, study guides, readings and links, all of which provide temporal and spatial flexibility. Online tutorials and noticeboards allow information to be passed effectively between students and academics.[28] This provides an additional opportunity for students to be enrolled transnationally via virtual classrooms.[29] Such development affects not only the research tools but also the opportunities for changing methods of research training, particularly postgraduate research training. For instance, research supervision in cyberspace is more feasible. Postgraduate research students can communicate with their supervisors via email, videolink and inexpensive internet‑based audio programs. They can post project timelines and literature reviews on the web to be simultaneously accessed by their supervisors.[30] Such web‑based tools are effective for providing feedback on student progress as they provide students with opportunities to organise, implement, report and then critically reflect on their research progress. These tools also provide the means to police the ethical use of sources through the use of commercial software which check documents for plagiarism.

The Australian higher education sector has been the subject of government intervention in recent years. There was a growth in the number of university law faculties under the Dawkins reforms,[31] which has meant more choice and competition in the market, but has also resulted in resources being allocated according to government‑driven policy and incentives. Some examples of government policy include the passage of the Higher Education Support Act 2003 (Cth)[32] implementing policies from Nelson’s report[33] and the establishment of the Australian Learning and Teaching Council (formerly known as the Carrick Institute for Learning and Teaching in Higher Education).[34]

Theresa Shanahan noted in 2006 that in Canada,

[o]ver the last 20 years there has been a shift in Canadian social policy, and thus higher education policy, away from a Keynesian welfare state towards global capitalism that reflects a neo‑liberal economic approach. This approach is characterized in the literature as championing the principles of market primacy, free trade, privatization, deregulation, decreased government intervention in the economy and social welfare, and increased community and non‑governmental organization involvement in social welfare to fill the gap.[35]

She has argued that these policies have had a flow‑on effect in higher education policy and research. She summarises research by Connie Backhouse, who pointed to

15 transformative factors in Canadian legal education as follows: reductions in university budgets; government demands for accountability and reporting; privatization of funding; hierarchical ranking of law schools; consumerism; marketing and competitiveness; internationalization; rapid change in the legal profession; technological change; demographic change; inclusion in the university academy; increased pace of academic work; tension between law faculty members; leadership; tensions between law schools and university administrators; and local factors unique to each law school.[36]

This discord in the university sector has also been documented in the research carried out by Margaret Thornton in Australia.[37]

These policy developments in Australia have led to increased subject specialisation through faculty‑ and university‑wide research strategies and centres, some of which focus on particular areas of law. These centres of excellence are being provided with more extensive funding, attract more PhD students and therefore have more opportunity to extend the research methodologies used than was previously the case.[38] Of course, foremost in these developments is the move towards government funding based on the perceived quality of the research taking place in the universities. This is measured in terms of research higher degree completions, peer reviewed publications in highly ranked journals and external research grants. Researchers are encouraged to plan their projects and schedules to maximise financial rewards from central‑ and government‑funded incentive schemes. There is more emphasis on interdisciplinary work (and a corresponding acceptance of the need for social science methodologies) along with the need for practical outcomes designed to foster strategic links with industry.[39]

There has also been more general recognition of an important link between research, knowledge, globalisation and a healthy economy. This has partly promoted the ‘vocationalist shift’ in the tertiary sector.[40] Thus the professional doctorate, more aligned with applied research primarily focused on industry objectives, has gained acceptance.

Erica McWilliam has pointed to other factors that have led to diversity, particularly within the postgraduate cohorts. These factors include: pressure for shorter completion times; increased marketing of programs in response to increased competition for students; and the call for greater access for ‘non‑typical’ cohorts — whilst still retaining the emphasis on quality.[41] Legal education has in turn been forced to react to these external demands. Research training has been affected as the focus has reverted to being more practitioner‑centred as at undergraduate level, rather than the pure academic research traditionally encountered in the PhD.

Modern educational theory is prompting teachers to adopt innovative approaches to teaching at the tertiary level. These educational approaches such as student‑centred learning and lifelong learning[42] set new challenges for legal research training.

Two of the best known authors in this area are Paul Ramsden and John Biggs. Ramsden’s work encouraged tertiary teachers to consider ‘[t]he idea of learning as a qualitative change in a person’s view of reality’ and to look at ‘deep learning’ rather than ‘surface learning’ approaches in their classes.[43] Biggs established that environmental factors such as increasing class sizes, student diversity and fees have placed additional pressures on tertiary teachers, requiring them to take a ‘fresh look’ at the teaching process.[44] He also suggested that ‘good teaching is getting most students to use the higher cognitive level processes that the more academic students use spontaneously’,[45] and particularly encouraged the use of reflective practice to address this issue.[46] These views are consistent with suggestions that educators develop an environment which emphasises the student’s role in the ongoing learning process and enables students to take a deeper approach to learning. Behaviourist theory, social cognition and experiential learning have all been recognised as having a role in developing more effective legal research training units.[47]

Both the Pearce Report in 1987 and the subsequent Australian Law Schools after the 1987 Pearce Report (‘McInnis and Marginson Report’)[48] in 1994 observed that the movement towards skills development within law schools had been slow prior to the Pearce Report. Research suggested that discipline knowledge was only one of a broader set of components that influence the success of a university graduate in their chosen profession.[49] The reports established that it was graduate attributes — the qualities, skills and understandings developed during the tertiary education process — that determined success in the workforce.[50] In the same vein, the Australian Law Reform Commission in its report on managing justice called for legal education to focus on what lawyers need to be able to do rather than remaining anchored around restrictive and outdated notions of what lawyers need to know.[51] This gave recognition to the fact that the traditional content‑based approach of the law school curricula was not adequately preparing graduates for changing workplaces.[52] The 2007 Educating Lawyers: Preparation for the Profession of Law report (‘Carnegie Report’) also acknowledged these concerns and advocated Cognitive Apprenticeship as a better educational framework than the Socratic Method or ‘case‑dialogue teaching’.[53] The Cognitive Apprenticeship approach advocates embedding ‘learning in activity’ and making ‘deliberate use of the social and physical context’.[54]

By 2003, the ‘stocktake’ of legal education in Australia commissioned by the Australian Universities Teaching Committee found that the largest change in law school curricula over the past decade had been the ‘infusion of skills education and training into LLB programs’.[55] In addition to the vocational aspect, Avrom Sherr noted that the inclusion of skills accords with ‘best practice’ in teaching and provides context to undergraduate legal problem‑solving resulting in a more ‘holistic approach’ to teaching.[56]

Legal research forms part of information literacy — a major graduate attribute.[57] Information literacy has been defined as ‘the ability to locate, evaluate, manage and use information from a range of sources for problem solving, decision making and research.’[58] The concept includes ‘computer skills, information technology literacy, … knowledge of database structures, library and research skills, problem‑solving, critical analysis skills, oral communication [and] written communication’.[59] In 2003, Natalie Cuffe developed an outline for undergraduate legal research units using information literacy as a conceptual framework.[60] She suggested that legal research incorporated two main components — information technology literacy and legal research skills.[61] The model Cuffe developed had three undergraduate legal research levels of achievement.[62] These theories formed another step in bolstering a reformed legal research training agenda.

Finally, there has been an increasing emphasis on quality assurance in education and research. It has been recognised that ‘[r]esearch postgraduate training is unique among academic responsibilities in providing a direct linkage between teaching and learning activities and research.’[63] Improved legal research training in both the undergraduate degree and at the postgraduate level are central to promoting quality research. The quality of outputs within the university will be improved by acknowledging and promoting this link. Therefore, modern educational theory has bolstered the theoretical underpinnings of the skills training process taking place in the law schools, which has added a new professionalism to the educational aspect of research skills training.

Australian trade in legal services is burgeoning. The General Agreement on Trade in Services[64] and the Australia–United States Free Trade Agreement[65] are opening up opportunities for law graduates to practice beyond Australia and for foreign lawyers to practice in Australia. Since 1994, when the General Agreement on Trade in Services was concluded, there has been provision for the liberalisation of the service industry and consequently an increase in export opportunities for professional services.[66] The last 10 years have thus witnessed much more cross‑jurisdictional work between the Australian states and territories with many more legal firms organised on a national basis. These changes have heralded a new environment of increased competition between universities and law schools, as well as a desire to make legal education more nationally and internationally relevant. This in turn is affecting the legal research paradigm because law schools now need to ensure graduates are skilled not only at researching the law in their own jurisdiction but also in international and comparative law.

In response, Australian law schools have been endeavouring to ‘internationalise’ their profiles and curricula.[67] The International Legal Education and Training Committee (‘Legal Education Committee’) of the International Legal Services Advisory Council (‘ILSAC’) looked at these issues in its 2004 report. The ILSAC report noted that law schools were taking many approaches to this issue. These included: ‘internationalising’ core subjects by integrating international and comparative materials; introducing new combined degree programs; instituting international exchange agreements and internships; arranging study tours to relevant international jurisdictions such as China; establishing Asian Law specialist centres; encouraging visits and lectures by international academics; cultivating an international network of alumni; marketing the law school’s program overseas; and offering postgraduate programs that specialise in international and comparative law.[68]

Such a study of international and comparative law is central to the new environment which requires transnational graduates with transferable research skills which enable them to work in the legal arena of foreign jurisdictions. The content of legal scholarship is changing to cater for the world view rather than simply the local law of one jurisdiction: for example, legal academics are publishing in international journals. Such a transition to a transnational agenda make legal research skills training even more necessary, as research is a practical legal skill required of modern lawyers in the global legal world.

All of these developments — information technology, government policy, new education theory and the trade in legal services — have challenged the old views of legal research. These developments build on changes that were taking place in the last two decades: Australia’s revised ‘sense of place in the world’ and its own rich national legal heritage; Britain becoming part of the European community; the increasing trade with the Association of South East Asian Nations countries; the ‘transformation of most of our populous neighbours to the north from subject peoples of European powers to independent nation states’; ‘the new nationhood of so many small Pacific Island states and our own position of relative importance to them both economically and in other ways’; and the end of the Cold War.[69]

Such a dramatically changed environment should be affecting the emphasis within legal research training. There are new electronic sources, and an impetus to provide quality, industry‑linked outcomes, with an emphasis on globalised research skills. The teaching methods need to match university aspirations of providing quality outcomes for graduates including the inculcation of university‑mandated graduate attributes. The emphasis on British sources and precedent has waned because of Britain’s alignment with the European Union, and the importance of exposure to Asian and Pacific legal research sources has increased. All of these forces have inspired the need for a revised legal research paradigm.

The challenge to elucidate the underlying paradigm is confronting as (unfortunately) the doctrinal legal research paradigm has been under‑theorised. It is based on assumptions which are so strong that they have not been properly questioned or examined.

Paradigms are shared world views, which determine what topics are ‘suitable’ to study, what methodologies are acceptable and what criteria may be used to judge success. John Jones’s definition of paradigms as ‘taken‑for‑granted mindsets’ presents a more tangible description.[70] According to this view, socialisation into the discipline is instrumental in ensuring that practitioners and academics adopt certain ‘ways of knowing’,[71] such as ‘thinking like a lawyer’.

The questions which emerge are ‘has legal research ever had an accepted paradigm?’ and, if so, ‘are contextual changes spurring a change in the paradigm?’ It has previously been suggested that one of the main difficulties facing legal scholars is the lack of a legal research paradigm.[72] Without a paradigm, Peter Ziegler warns that all factors may seem equally relevant. All research, including every exploration of case law or legislation, may be equally random and equally valid. This can lead to ‘neological seduction’ — the seduction of the new or the latest theoretical fashion.[73] Thus, it could be argued that legal research has been plagued by a lack of cohesion in terms of the projects undertaken and the development of research depth. Individuals have taken up the bandwagon on certain issues, developed the ideas within a pragmatic, practice‑driven agenda, but have then been diverted away from their topic, often because of a lack of resources, a lack of team management skills, and the need for multi‑disciplinary methodologies and knowledge. The accepted paradigm for lawyers has been doctrinal research.

The term has not been defined or categorised in relation to other research methods.[74] The new electronic sources and modern research contexts require legal researchers to engage in more than a restrictive doctrinal research methodology. This in turn requires that a legal research skills training framework be developed which meets that need. This includes:

• placing an emphasis on the research process rather than research sources when teaching research;

• recognising the need to move outside the narrow ‘black letter’ doctrinal methodology research box[75] to a broader paradigm for law that involves interdisciplinary work and a range of methodologies borrowed from the social sciences and humanities;

• integrating the research and writing processes so that legal writing genres become an integral part of the research curriculum;

• enhancing gradually research knowledge and abilities by following a ‘point of need’ approach to training;[76] and

• emphasising the different pathways available for research skills training, in particular the legal academic scholarship model in conjunction with the traditional legal practitioner model.

There is currently a need for an evolving paradigm which includes a more outward‑looking focus encompassing interdisciplinary methodologies. Internationalisation, globalisation and economic rationalism — all inspiring transnational and certainly more cosmopolitan views — are therefore forcing a less cloistered or parochial approach to legal problems. This needs to be reflected in the research training in law schools.

The standard legal research texts in Australia and the common law jurisdictions are evidence of an old paradigm. They have been written on the basis that there is only one legal research methodology — the doctrinal method — and that this methodology requires no explanation or description. For these texts, all that is required is an explanation of how to use legal research reference books and research sources.[77] This is termed a ‘bibliographic approach’ to teaching the doctrinal legal research methodology.[78]

The better approach to teaching legal research is by asking the student to track and reflect on their ‘research process’. This more recent approach builds on the ideas put forward in the US by Christopher Wren and Jill Wren, but very much applies to the Australian tertiary context.[79] Wren and Wren proposed

an instructional method that focuses on the legal research process ([that is], gathering and analyzing facts, identifying and organizing legal issues, finding legal authorities, reading and synthesizing authorities, and determining whether the law is still valid) …[80]

They explained that

[t]hrough process‑oriented instruction, students acquire not a narrow conception of how to use law books, but a broad understanding of how to draw creatively and comprehensively on various law books in developing a problem‑solving strategy.[81]

In doing this they highlighted the importance of identifying a research methodology and process rather than simply focusing on an ability to use the legal research sources.

Law has had a research paradigm based predominantly in the doctrinal methodology. It has been based in liberal theory and positivism, and a framework of tracing common law precedent and legislative interpretation. Included within the legal doctrinal paradigm umbrella are some expanded and well‑accepted legal research frameworks, namely legal theory research, law reform research and public policy research. These categories have tended to challenge the frontiers and boundaries of legal development, with the first two identified in the Pearce Report and all three in the Arthurs Report.[82] These are all established extensions to the doctrinal method and are widely used by legal researchers.

The theoretical research methodology examines the historical development of the theory of law itself and frequently uses theory as a springboard to critique existing law, legal reform and practice. The model for reform research is based on the research methodologies used within the law reform commissions to provide advice on changes to existing law. While public policy research has many common aspects with law reform research, it emanates from within government and hence tends to have a more pragmatic approach.[83] These expanded frameworks often incorporate empirical research methodologies into traditional doctrinal methodologies, at least to some extent.

Today’s lawyers are moving into a new research world in which it is necessary to know, use and be able to critique the results of a whole variety of methodologies in addition to the known doctrinal methodology. These other methodologies include qualitative and quantitative methods taken from the social sciences, and also comparative research, case studies, benchmarking and content analysis, all of which are particularly suited to legal research. The new legal research environment thus includes:

• new methodologies borrowed from the social sciences;

• interdisciplinary perspectives blending law and medicine and the ‘hard’ sciences;

• team approaches to research;

• doctoral and post‑doctoral academic perspectives alongside the dominant practical and professional perspectives;

• a firm acknowledgement of the importance of underlying theory in explaining law, including both social theory and the philosophy of the law;

• an acknowledgement of individual differences in the intellectual framework for research including functional and theoretical perspectives on law;

• a sensitive and methodologically sound approach to comparative law and research; and

• an acceptance of the substantial impact of international law on national agendas.

The crucial importance of empirical research to law was recognised in the UK in 2004 when the Nuffield Foundation funded a major inquiry into the ‘UK’s capacity to carry out empirical research on how law works in the real world’.[84] The recommendations included the following:

xii We recommend that all law departments should consider enhancing the undergraduate curriculum by offering an option on law in society, or offering options with a significant empirical content. … This would better equip students to deal with a world in which there is an increasing demand for assembling and analysing social data and where, indeed, legal practice requires a wide range of research skills in addition to those of the doctrinal lawyer. Such students should also acquire the technical skills needed to analyse data.[85]

No doubt it is impossible to include any depth of research training for all the possible methodologies within a law curriculum, but opportunities for such training within the law degree are currently very limited. Some Australian law students enter law school with prior studies including research methods units. Some enrol in combined degree courses that include interdisciplinary research training. Some of the first year law context‑directed core units may include very basic social science research methods training or exposure. Some law degrees make provision for students to take research electives from other disciplines. A 2002 survey of Australian law teachers asked ‘whether social science or empirical methodologies were covered in the research units’. Only five respondents reported that these methodologies were taught within the undergraduate degree units. Three said that there were separate elective units covering these issues. Only two of the postgraduate units had this training included.[86] In March 2008, an examination of 29 Australian law school websites demonstrated that very few courses explicitly included empirical training in their law degrees. The research units that did feature tended to be divided into three categories — Law and Psychology, Law and Justice/Criminology, and Law and Socio‑Legal Research.

Anecdotally, there seems to be limited empirical research being carried out by students within undergraduate law degrees in Australia and only a modicum of empirical methodologies being used at law schools at the Masters coursework level. Many law courses have a research project elective in the undergraduate degree, but very few students undertake empirical work for these because the projects tend to be limited to one semester. This is also true for the Masters research project units. One semester of 13 weeks does not provide sufficient time to carry out an ethics application and draft even a simple survey, let alone administer that survey, analyse the results and report on the outcomes. Few professional doctoral students in law would undertake an empirical study and surprisingly few PhD students. However, increasingly successful academic competitive grant applications include empirical methodologies, providing a strong argument in support of changing the legal training emphasis to a focus on empirical methods. We need to close the gap between research training and academic research career expectations.

Robert Ellickson’s study of legal scholarship trends in the US from 1982–96 demonstrates that empirical research is increasing in that jurisdiction.[87] Shanahan’s study of legal scholarship in Canada in 2001 is also pertinent.[88] Her study shows that legal academic researchers want to use empirical methodologies rather than undertake purely doctrinal research methodologies. In some cases the academics do use these methodologies, but in many cases their research demonstrates that they require more expertise and training in empirical methodologies to use them effectively. Shanahan comments that

[i]t is apparent from both the survey data and interview findings that interdisciplinary research has increased in the past 20 years, as have the range of subject areas, and the geographic, ideological and theoretical orientation of legal research. However it appears as if law professors are still methodologically limited in their range of approaches, and especially in their use of empirical research. The findings suggest that law professors’ range of activities continues to be narrow and lacks the sophisticated qualitative and quantitative research techniques found in the social sciences. As was the case 20 years ago, empirical research methods are still seldom used and few professors generate empirical data according to the findings (3% of the research projects reported). At the time of the Law and Learning Report the prevalence of doctrinal analysis in law professors’ research was reported. The findings from the interviews in this study suggest that doctrinal analysis is decreasing, disfavoured and even denigrated in the academy. By contrast the survey data showed doctrinal research as the second most common approach used in research projects described by law professors, employed in 25% of the reported projects. Legal theory was the most frequent theoretical framework adopted in almost one third of the research projects reported by the participants of the study.

The study showed law professors using multiple theories and methods in their projects. Unsupported by research training this may indicate that they are dabbling lightly in various methods and perhaps with some confusion. For example, the data revealed almost 10% of survey participants reported “theory” as their research methodology suggesting they did not clearly understand the difference between one’s research method and one’s theoretical framework. However, the survey data suggests increasing levels of cross‑disciplinary appointments, and interdisciplinary research conducted by law professors — perhaps evidence that law professors are becoming increasingly integrated into the university and becoming influenced by other forms of scholarship.[89]

These developments in research scholarship which anecdotally are also occurring in the Australian legal academy underscore the need to introduce basic empirical research methodology training at the undergraduate level. An ability to understand, appreciate and critique methodologies (other than doctrinal methodologies) is now fundamental to good legal scholarship. This may be an exercise as simple as critiquing a survey or its results, or being introduced to the variety of research methodologies and their basic components. In this way, law students will at least graduate with an understanding of the range of research methodologies and theoretical frameworks, which will be useful for them whether they practice, teach or research the law.

The changed agenda means that legal research currently has an opportunity to be liberated from the chains of its previous narrow doctrinal framework. This constitutes a blossoming of the legal research environment and a move away from a constrained and outdated paradigm. At the very least, law students need to graduate with knowledge of the full range of methodologies available to researchers in addition to the doctrinal method. More importantly, they need to have the skills and knowledge to be able to critique non‑doctrinal methods effectively. This can be accomplished most successfully by introducing non‑doctrinal methodologies in compulsory first year units and then following up with a wider choice of electives later in the degree for those minded to indulge in a more academic and critical view of the law.

Good communication skills are inextricably linked to research skills — what is the use in researching the law if the results cannot be effectively communicated to an interested audience and applied in deepening public understanding of the effectiveness of legal rules in society? This vital nexus needs formal acknowledgement in the research curriculum.

As each step in the educative process occurs, pertinent new writing genres should be introduced. By their final undergraduate law units, students should know how to research and have the writing skills necessary for practical lawyering, in pieces such as assignments, case notes, client‑focused emails, letters to clients, research memoranda, barristers’ opinions and solicitors’ firm newsletter articles. For instance, having the ability to write a clear letter to a client or a research memorandum to a senior partner in a law firm would show students that they should be aware of the difference in style and content between these two. Capstone or final year research units provide an opportunity to introduce students to the importance of being able to write a clear descriptive article for a firm newsletter for clients. These are all very practical skills.

Extensions can also be made to practice‑oriented research communication skills during the legal practice courses. Most legal writing genres will be covered during the undergraduate years — including assignments, letters, research memoranda and law firm’s client newsletter articles. Students might also look at the requirements for a useful barrister’s opinion as a precursor to their work experience. Emphasis must be placed on the context of communication, as good communication tools are fundamental to relaying information to facilitate transnational practice where so much work is done by proxy — by letter, email, and telephone.

Other writing genres are better suited to postgraduate development and academia. Some of these writing genres such as research papers are developed generally in the early years of the undergraduate curriculum but must be revisited and extended at upper level undergraduate and postgraduate levels. The ability to write a cohesive research proposal and a thorough literature review are intrinsic to higher degree research. Some of the writing genres specifically required for legal scholarship in academia are research proposals, literature reviews, journal articles, grant applications and theses.

The overarching importance of good legal writing has a strong hold on the US legal education sector as is evident by the title of the research and writing programs and associations.[90] There is no need for tension between the relative importance of research and writing pursuits within programs. These two are tightly linked and this needs to be firmly acknowledged within the curriculum.

As mentioned earlier, there are two principal results‑driven models for research training, constituting two divergent vocational streams. These two paths represent the hybrid nature of the law school, made up of a blending of the ‘historic community of practitioners’ and the ‘modern research university’, a dual heritage identified in the 2007 Carnegie Report.[91]

The two streams result in two separate types of research endeavour. First, there is academic research and specific training required to bolster the progression towards academic scholarship. Secondly, there is practitioner research and specific training for praxis. These differences in levels and objects in the curriculum are often conflated.[92] The first is an academic scholarship‑driven research model. The second model is a legal practitioner‑driven model of research training. This requires acknowledgement that the research that takes place in law faculties is not simply the same kind of research that law firms do ‘only with more countries and a longer timeframe.’[93]

Mary Keyes and Richard Johnstone have pointed to the assumption that ‘the dominant purpose of legal education is preparation for legal practice’ as one that has prevented progress in legal education.[94] Thus, perhaps too frequently in Australia, the practitioner‑driven model of research training based in the old doctrinal paradigm has predominated, and insufficient planning has been directed to developing research skills more suited to academic research. This of course is best developed during the later year undergraduate and postgraduate levels.

Undergraduate and Postgraduate Research Training

Legal Practitioner Model

Practice

Academic Legal Scholarship Model

Academy

Figure 3

Research training at its most basic level is similar for each purpose. Both the academic and practitioner streams need to have a thorough grounding in Australian legal structures and to be able to research Australian and the main common law jurisdictions. Both need proficiency in the doctrinal research method. Both streams need to have initial training in writing assignments. However, most practitioners will not need to write a research proposal or undertake a full literature review. They will have little need to actually formulate a research problem. They may never have to conduct a survey or take part in interdisciplinary research. While these skills are normally only requirements for academic research, practitioners will need to have some awareness and ability to critique the interdisciplinary and group research which they may access in preparation of cases for their clients.

On the other hand, academic researchers will almost always need solid practical legal research training. This is because academics are often called upon to research aspects of the law in practice. There is an abiding nexus with information flowing from the academy back to inform practice. Therefore an academic scholarship‑driven research model is necessarily an extension of the basic practical research training, and that model is likely to be focused on a smaller undergraduate student cohort who will be aiming to further their studies at the postgraduate level.

There are several opportunities within the law curriculum for progressing research education including targeted undergraduate first year and later year research units, elective research project units for upper year levels, the legal practice units, postgraduate research training units, mooting units and also extra training for research assistants’ positions. For example, research mentoring of ‘honours’ students by faculty through enhanced training in research assistant positions can be a particularly effective training mechanism.[95]

Legal research must be introduced gradually at the ‘point of need’.[96] If information and skills training is provided when it is intrinsically necessary for the student, these skills are more likely to be practised and the knowledge retained. In the undergraduate degree, students need an initial introduction in first year, to be followed by an enhancement and compounding of the basic skills in the later years. Additional depth and skill is required when the students attempt assignments and more again is required to complement advanced activities such as advocacy and mooting. This incremental approach to skills development throughout the degree stands in comparison with ‘the “one shot” or inoculation model of teaching … characterised by having one skills unit at the beginning of the course and a “booster” unit/shot at the end’.[97]

Legal research training needs to be developed around this ‘point of need’ approach. Undergraduate students need basic research training according to their course requirements, whilst postgraduate students need a different focus and level of training. There are a variety of programs through which students progress including legal practice courses, Masters by coursework, Masters by research thesis, PhD research and the SJD or professional doctoral program research. All of these stages have specific and differing objectives, and the research education the cohorts are offered should be incrementally more advanced, building on prior knowledge.

Research training needs to be mandatory in the first year of the law degree. At this point, students require a broad introduction to the range of research methodologies available to them as well as a more focused doctrinal training. Focusing on the doctrinal method, law students at this point need an introduction to the local state legal system and research strategies for the federal jurisdiction. Public international law and the access and use of treaties need to be introduced at a relatively early stage. Before graduating, this international knowledge should be reinforced.

Students also require a solid grounding in electronic searching techniques, basic legal writing genres and legal citation. There has been much debate on whether this training should occur as a separate compulsory unit, as part of another substantive unit or as part of a law in context unit.[98] Should there be a basic introduction in the first weeks of semester followed by an assessed follow‑up unit later in the first year? These issues would seem to depend on resource implications based on student numbers, staff numbers and physical resources in the library and computer laboratories. However, this introductory unit needs to be compulsory and assessed, so that it is taken seriously by the student cohort.

Figure 4

Undergraduate Research Project Units

First Year Research Unit

Development of Research Skills in Substantive Units

Research Assistants’ Positions and Mentoring Programs

Moots, Legal Theory, Interdisciplinary Research Units

Legal Practice Course

Postgraduate Courses:

LLM, SJD, PHD

Final Year Research Unit

Opportunities for Developing Research Skills

Substantive units throughout the degree can reinforce and update basic research training, but there can be challenges in introducing research skills in substantive core units. These include: the likelihood that content will take precedence over skills in terms of teaching time and assessment; the likelihood that the teaching staff will not themselves be fully cognisant of the skills or how to teach them; the time, goodwill and cost involved in ensuring substantive staff are trained and adhering to the requirements of the skills program; and the additional marking involved in assessing skills. A simple option is to embed a research component within an assessed assignment for at least one core unit at each level of the degree. It is in these assignments that students should encounter law from comparative Australian jurisdictions. Students will have been introduced to their own state law, Commonwealth law and public international research in first year, but the next skills levels need to include a research comparison with other states in Australia. Such written and oral assignments, advocacy or moot assignments ensure students have practice in critique, citation and writing skills.

Moots and theory units are standard vehicles for introducing research training. In both units, the students are required to move beyond the texts and read, critique, analyse and communicate research outcomes. Other elective units that have an intrinsic research component are the supervised research project units and interdisciplinary elective units such as those from other schools — for example, criminology or justice studies. This group of elective units are those most useful to students intending to undertake further study because they focus on training students in academic scholarship through additional methodologies training and the individual supervision provided by academic mentors. The research projects are also an introduction to research proposal formulation and academic scholarship writing standards.

A final year ‘capstone’ research unit provides an opportunity to ensure that these skills have been developed to a required standard for legal practice purposes. It also provides an opportunity for students to update their database research skills — that is, their electronic research skills. It is an opportunity to update students’ research knowledge by extending doctrinal research into different jurisdictions in their final year. It also provides an opportunity to introduce students more thoroughly to researching comparative jurisdictions such as the US, Canada and the European Union. This broader world view inspired by comparative and international research is part of the new transnational paradigm, not the least because it ‘confronts students with the non‑inevitability of the law of their own country.’[99] A ‘capstone’ unit fosters the ability to deal with several mixed issues by giving students interrelated subject content problems.

Furthermore, research assignments only assess law students on one subject. Later year students should be able to confront problems that span two or three areas so that they experience ‘real world’ rather than closed book, problem‑based learning. This also allows students to update their knowledge of major substantive areas of law studied in first and second years — areas where major changes in legislation and case law are likely to have occurred in the interim. These later year units are an opportunity to introduce students to additional practical legal writing genres, such as letters to clients and research memoranda to senior partners. In this way, students may progress to the workplace with finely tuned research and communication skills.

Figure 5: Research Training Continuum — A Jurisdictional Approach for a Local State Jurisdiction

Federal Jurisdiction

Public International Law

Civil Law Basics

Other State Jurisdictions in Australia

United Kingdom

Canada

United States

European Union

New Zealand

South Pacific

India and Asia

Four Year Degree Program

Research assistant positions offer more focused students another opportunity for individually mentored research instruction, and there are a myriad of positive outcomes for students who undertake these positions. Some of the tasks these students will experience model the academic research process, including the writing of literature reviews, the organisation of located research sources, the use of personal research databases, additional methodologies training such as ‘sampling and data collection techniques, … ethical research conduct (and safety practices), … [and] the development of a good knowledge of interlibrary loan procedures’.[100]

Legal practice units are another opportunity to update students with research in the legal practitioner model. This will include an introduction or update on sources more applicable for practice such as forms and precedents. It will also include research strategies for situations where it is important to provide the right answer quickly and succinctly. This is another opportunity to reinforce practical writing genres.

Postgraduate academic research training develops all the skills from the undergraduate level but specifically focuses on the academic legal scholarship model. There are stages of development at postgraduate level but the advanced research units form a skills basis.[101] The PhD provides the pinnacle of postgraduate research training. Coursework Masters units provide opportunities for smaller supervised projects and coursework research assignments. A coursework Masters research unit may provide the first step in guiding students towards this ultimate focus. The research unit inculcates skills such as preparing research proposals, writing literature reviews, and managing and progressing extended research projects. It provides researchers with experience in achieving originality in their work and experience in moving beyond a purely descriptive analysis of the law. A basic postgraduate research unit will provide the student with experience in structuring complex writing projects and following through on legal arguments, while also providing vital experience in presenting research projects to a group of peers and supervisors. All are excellent ‘baby steps’ towards more extensive supervised projects.

Thus, research skills need to be developed at different stages of education and practice. In one sense, this training and development never has an end point. There is an ever‑present need to update skills so that lawyer‑researchers can become lifelong learners, able to function in ever‑changing practice and academic research environments where new law and new endeavours prevail.[102]

Legal research is now taking place in an expanding paradigm built on interdisciplinary perspectives, broader research objectives, enhanced writing requirements and an extensive choice of methodologies. Increased focus and financial imperatives at both the national and international level have ensured that there is a need for thought and planning to be directed to pertinent training. This is an exciting time for legal researchers: the methodological choice is broadening, whilst at the same time originality and the possibility of an international arena are enhancing the scope and applicability of research endeavours and the requirements for solid legal research training.

Legal research training units are a fundamental key for the new transnational era. Enhancing research units is an important first step in finding solutions to the research issues facing the modern profession.[103] Legal research training can no longer be wrapped within a narrow doctrinal methodology and bound to a stagnant practice‑focused paradigm. Legal research is a threshold skill, whether the researcher’s focus is praxis or academic publication. Legal research training must be brought into line with the current context for lawyers. The traditional, under‑theorised doctrinal paradigm of legal research is no longer sufficient for modern lawyers, and exposure to additional methodologies must be included in research training units. Legal research skills education has changed, but it must continue to develop in order to more fully meet the needs of students, the profession and the academy in the contemporary legal environment.

[*] BA, LLB (UQ), DipLib (UNSW), MLP (QUT), PhD (Griffith); Senior Lecturer, Faculty of Law, Queensland University of Technology.

[1] Faculty of Law, Queensland University of Technology, Legal Research Profile (1992). See also Council of Australian Law Deans (‘CALD’), The Research Quality Framework (RQF): Responses to the Issues Paper (2005) <http://www.dest.gov.au/NR/rdonlyres/62C38170-6F41-45F1-9180-D0065FB33089/6011/RQF010117CALD.pdf> .

[2] Dennis Pearce, Enid Campbell and Don Harding (‘Pearce Committee’), Australian Law Schools: A Discipline Assessment for the Commonwealth Tertiary Education Commission (1987) 307–8.

[3] Sue Milne and Kay Tucker, A Practical Guide to Legal Research (2008) 1. See also CALD, Statement on the Nature of Legal Research (2005) <http://www.cald.asn.au/docs/cald%20

statement%20on%20the%20nature%20of%20legal%20research%20-%202005.pdf>.

[4] It was reported in a 1991 survey that only two faculties in the respondent group had no formal courses in legal research. Nine schools had separate research subjects and seven taught legal research as a component of another subject, invariably the first year ‘Introduction to Law’ unit: Terry Hutchinson, ‘Legal Research Courses: The 1991 Survey’ (1992) 110 Australian Law Librarians Group Newsletter 87, 88. See also Robert C Berring and Kathleen Vanden Heuvel, ‘Legal Research: Should Students Learn It or Wing It?’ (1989) 81 Law Library Journal 431; Sharon Christensen and Sally Kift, ‘Graduate Attributes and Legal Skills: Integration or Disintegration?’ (2000) 11 Legal Education Review 207, 213.

[5] See generally Terry Hutchinson, Legal Research in Law Firms (1994) 28–49; MSJ Keys Young, Legal Research and Information Needs of Legal Practitioners: Discussion Paper (1992); Avrom Sherr, Solicitors and Their Skills: A Study of the Viability of Different Research Methods for Collating and Categorising the Skills Solicitors Utilise in Their Professional Work (1991); Kim Economides and Jeff Smallcombe, Preparatory Skills Training for Trainee Solicitors (1991); Christopher Roper, Senior Solicitors and Their Participation in Continuing Legal Education (1993); Deedra Benthall‑Nietzel, ‘An Empirical Investigation of the Relationship between Lawyering Skills and Legal Education’ (1975) 63 Kentucky Law Journal 373; Robert A D Schwartz, ‘The Relative Importance of Skills Used by Attorneys’ (1973) 3 Golden Gate Law Review 321; Gerard Nash, ‘How Best to Refresh Our Legal Knowledge’ (Paper presented at the 7th Commonwealth Law Conference, Hong Kong, 18–23 September 1983) 222–3; John K de Groot, Producing a Competent Lawyer: Alternative Available (1995) 2–3; J A Smillie, ‘Results of a Survey of Otago Law Graduates 1971–1981’ [1983] OtaLawRw 6; (1983) 5 Otago Law Review 442, 450; Frances Kahn Zemans and Victor Rosenblum, ‘Preparation for the Practice of Law — The Views of the Practicing Bar’ (1980) 1 American Bar Foundation Research Journal 1, 5; Leonard L Baird, ‘A Survey of the Relevance of Legal Training to Law School Graduates’ (1978) 29 Journal of Legal Education 264, 273–4; The Committee on the Future of the Legal Profession (‘The Marre Committee’), A Time for Change: Report of the Committee on the Future of the Legal Profession (1988) 113; John R Peden, ‘Professional Legal Education and Skills Training for Australian Lawyers’ (1972) 46 Australian Law Journal 157, 167.

[6] Michael Chesterman and David Weisbrot, ‘Legal Scholarship in Australia’ (1987) 50 Modern Law Review 709, 710.

[7] Pearce Committee, above n 2.

[8] Ibid vol 3, 17.

[9] Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, Law and Learning: Report to the Social Sciences and the Humanities Research Council of Canada by the Consultative Group on Research and Education in Law (1983) 66.

[10] See Australian Bureau of Statistics, Australian Standard Research Classification (ASRC) 1998, ABS Catalogue No 1297.0 (1998) <http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/0/2d3b6b2b68a 6834fca25697e0018fb2d> . For the current scheme, see Australian Bureau of Statistics, Australian and New Zealand Standard Research Classification (ANZSRC) 2008, ABS Catalogue No 1297.0 (2008) <http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/Latestproducts/809BF4F37565C3

7ECA2574180004B6EA>.

[11] Australian Bureau of Statistics, Australian and New Zealand Standard Research Classification (ANZSRC) 2008, above n 10, ch 2 <

http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Latestproducts/ 1297.0Main%20Features42008>.

[12] Australian Bureau of Statistics, ARC Proposals Received and Funded for Legal Research, Since Submit Year 2001 (2008).

[13] Email from Yong Jiang (Officer of the ARC) to Terry Hutchinson, 31 October 2008.

[14] Hilary Charlesworth, ‘Challenges for Legal Research in Australia’ (Paper presented at the Australasian Law Teachers Association Conference, Victoria University of Technology, Melbourne, 4–7 July 2006) 3. ‘RFCD’ refers to Research Fields, Courses and Disciplines Classification: Australian Bureau of Statistics, Australian and New Zealand Standard Research Classification (ANZSRC) 2008, above n 10, ch 3 <http://www.abs.gov.au/Ausstats/abs@.nsf/Latest

products/1297.0Main%20Features52008>.

[15] Department of Education, Science and Training, Research Quality Framework: Assessing the Quality and Impact of Research in Australia — Issues Paper (2005).

[16] Ibid.

[17] Andrew Brennan and Jeff Malpas, ‘Researchers Drowning in Sea of Paper’, The Australian (Sydney), 16 April 2008, 25.

[18] Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations, Review of Australian Higher Education (2008) <http://www.dest.gov.au/sectors/higher_education/policy_issues_reviews/

reviews/highered_review/default.htm>.

[19] Australian House of Representatives Standing Committee on Industry, Science and Innovation, Inquiry into Research Training and Research Workforce Issues in Australian Universities (2008) Parliament of Australia <http://www.aph.gov.au/House/committee/isi/research/index.htm> .

[20] Department of Innovation, Industry, Science and Research, Review of the National Innovation System (2008) Department of Innovation, Industry, Science and Research <http://www.innovation.gov.au/Section/Innovation/Pages/ReleaseOfTheReviewOfTheNational

InnovationSystem.aspx>.

[21] Department of Education, Science and Training, above n 15, 3; Australian Research Council (‘ARC’), Consultation Paper: Excellence in Research for Australia (ERA) Initiative (2008) <http://www.arc.gov.au/era/consultation.htm> .

[22] CALD, above n 1, 3 (emphasis in original).

[23] Ibid.

[24] See, eg, Westlaw’s Key Number System.

[25] See, eg, the Queensland Legal Information Retrieval System (QLIRS), established to consider options for making legal information publicly available. For information, see G W Greenleaf, A S Mowbray and D P Lewis, Australasian Computerised Legal Information Handbook (1988) 34. Another example is AustLII <http://www.austlii.edu.au/> .

[26] Colin Fong and Terry Hutchinson, ‘Evaluating Australian Legal Research Guides on the Internet’ [2000] UTSLawRw 5; (2000) 2 University of Technology Sydney Law Review 47, where Fong and Hutchinson provide a criterion that lawyers should use in evaluating websites.

[27] Brendan Nelson, Our Universities: Backing Australia’s Future (2003) 31–3 <http://

www.backingaustraliasfuture.gov.au/policy_paper/policy_paper.pdf>.

[28] Terry Hutchinson, ‘Using the Internet for Research Training: Project Timelines, Reflective Journals and the Foundations Project’ (Paper presented at the Association of American Law Schools Conference on Educating Lawyers for Transnational Challenges, Hawaii, 26–29 May 2004) 1.

[29] Technological advancements in teaching are discussed in Michael A Adams, ‘Special Methods and Tools for Educating the Transnational Lawyer’ (Paper presented at the Association of American Law Schools Conference on Educating Lawyers for Transnational Challenges, Hawaii,

26–29 May 2004) 4.

[30] Hutchinson, ‘Using the Internet for Research Training’, above n 28.

[31] J S Dawkins, Higher Education: A Policy Statement (1988).

[32] For the objects of the Act, see Higher Education Support Act 2003 (Cth) s 2.1.

[34] Australian Learning and Teaching Council, About Us (2008) <http://www.altc.edu.au/carrick/

go/home/about>.

[35] Theresa Shanahan, ‘Legal Scholarship in Ontario’s English‑Speaking Common Law Schools’ (2006) 21(2) Canadian Journal of Law and Society 25, 32.

[36] Ibid. See further Connie Backhouse, ‘The Changing Landscape of Canadian Legal Education’ (Paper presented at the Excellence, Competition and Hierarchy Workshop on the Future of Canadian Legal Education, University of Manitoba, 3–4 May 1999).

[37] See, eg, Margaret Thornton, ‘The Law School, the Market and the New Knowledge Economy’ (2007) 17 Legal Education Review 1.

[38] Kim Carr, Minister for Innovation, Industry, Science and Research, Australian Government, ‘New ERA for Research Quality: Announcement of Excellence in Research for Australia Initiative’ (Media Release, 26 February 2008) <http://minister.innovation.gov.au/Carr/Pages/NEW

ERAFORRESEARCHQUALITY.aspx>.