Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance |

|

|

|

While the notion that communities require resources in the form of financial capital for their development and wellbeing has long been recognised, it has become increasingly apparent that economic resources alone do not lead to community sustainability and wellbeing. The building and supporting of strong, safe, socially cohesive communities that embrace social connections and commitment, has become an important goal of policy and initiatives at all levels of government. The aims of this study were to identify a common understanding of the concept of ‘community cohesion’, and to develop a set of indicators based on both the experiences of residents in a rural community and the relevant contemporary academic literature. Because community cohesion is an intangible concept subject to multiple meanings, qualitative research methods were used. We identified four main themes which could be translated into the key indicators. The most significant finding is that neighbourliness was identified by participants as the key aspect of community cohesion. Yet, whilst it is central, this does not mean excessive familiarity or the taking of liberties. Indeed, part of neighbourliness involves respecting each other’s boundaries and respect for diversity.

Key words: Indicators, community cohesion, social exclusion/inclusion, social capital.

While the notion that communities require resources in the form of financial capital for their development and wellbeing has long been recognised, it has become increasingly apparent that economic resources alone do not lead to community sustainability and wellbeing. This re-evaluation has led to the recognition that combinations of resources are needed to foster community wellbeing, including natural capital, economic capital, institutional capital, human capital and social capital. Of these various capitals, social capital is the least concrete but can be

understood to mean the social networks that link people to form a cohesive community (Stone and Hughes 2002a).

In Australia concerns about social capital and community cohesion have emerged as an area of key interest to a large number of government agencies aiming to combine community building and a whole of government approach to policy (Australian Bureau of Statistics [ABS] 2002). Indeed, the building and supporting of strong, safe, socially cohesive communities which embrace social connections and community life, has become an important goal of policy and initiatives at all levels of government, including local government. But how are strong, safe, socially cohesive communities measured? What are the indicators of such communities? As noted in the 2004 report Indicators of Community Strength in Victoria (Strategic Policy and Research Unit 2004), although there is useful information regarding tools for measuring such concepts, few indicators for determining community cohesion have been institutionalised in Australia.

The authors were approached by a small inland local council in Northern New South Wales to develop a set of indicators of community cohesion for a particular locality in the local government area, which could then be used by the council’s social planners in order to develop strategies aimed at increasing safety and cohesiveness. The population of this locality is approximately 12,000 persons with a median age of 35, and a median weekly household income of $600 - $699 (ABS 2001). Research has identified this area as being in the top 30 most disadvantaged areas in New South Wales and Victoria (Baum et al. 2002; Vinson 2004).

Community cohesion is an intangible concept subject to multiple meanings. Thus its definition can pose problems for quantitative (statistical) approaches, though these are useful for measurement once meanings and definitions have been decided upon. Important inroads have been made in this respect in the UK (Coutts et al. 2007; Home Office Community Cohesion Unit 2003). However, qualitative research methods are more appropriate when the aim is to tap into people’s perceptions, experiences and understandings. Quantitative methods have made a valuable contribution to the field in the UK by operationalising and developing measures of community cohesion as expressed through a national target – Public Service Agreement 21 (Cabinet Office Third Sector 2007). Qualitative methods can complement this work by eliciting and interpreting meanings which can then be translated into indicators.

Of initial importance to this research project was defining and determining what is commonly meant by the concepts of ‘community’ and ‘community cohesion’. This was done through reviewing relevant contemporary academic literature and consulting with the targeted community. Subsequently, key questions were developed in an attempt to determine social issues that currently impact on local residents. These were then put to the participants in the project, and from this data, indicators of community cohesion identified. There is a paucity of research using this approach, particularly in the Australian setting. This study, then. lends a new dimension to the existing body of work.

The theoretical framework for this qualitative research project is underpinned by the conviction that consulting with the community is the most effective method of arriving at sound conclusions that reflect the understandings and wishes of the public. This in turn is based on an epistemological position derived from feminist methodology, which holds that knowledge gained from the standpoint of the individual’s experience is valid and must be taken into account (Haraway 1991). This aligns well with Giddens’ (whose views have had considerable influence on social policy in the UK) notion of individuals as ‘knowledgeable agents’ (Giddens 1984). That is, individuals are imbued with a great deal of knowledge about their social world and are capable of exercising meaningful choices (Bilton et al. 1996). Data was collected using a three-pronged strategy, using structured questionnaires, focus groups and interviews. Each of these methods has a particular strength, and using more than one method allows a more valid outcome as it produces additional information as well as the opportunity to check and confirm data.

The areas of concern to this study relate to four closely linked concepts: community, social capital, community cohesion and social inclusion/exclusion. Issues relating to all four concepts play a key role in addressing social concerns within communities (Bridge et al. 2003; Harkness and Newman 2003; Nevile 2003; Vinson 2004; Waters 2001).

The concept of community as an aspect of group life has been defined by Hunt and Colander (1996:129) as “a group of people who live in a local area and who therefore have certain interests and problems in common.” The ABS (2002:5) notes that the concept of community can “refer to either place-based or non-place-based communities.” Place based communities are considered to exist at geographic levels such as in neighbourhoods, workplaces, suburbs, towns, districts and regions, states and countries and even globally. Non-place communities are considered to consist of groups with common interests such as sports clubs and issue-based action groups (ABS 2002). This study used a place-based definition, which was regarded as more appropriate given that the community being studied was defined geographically, with its own set of particularities and characteristics.

Although the notion of ‘community’ is often associated with connotations that involve caring and cooperation between neighbours, this is not always the case. For example, the German sociologist Frederick Toennies identified two forms of community: gemeinschaft in which a common set of values involving caring and cooperation are shared between community members; and gesellschaft in which relationships between community members are uncaring and distant. Nevertheless, the notion of community is more often ascribed to a largely ‘traditional’ and cohesive way of life in which people know one another and hold common values in relation to their local area (Hunt and Colander 1996).

Community cohesion involves interdependence and shared loyalties between members of a community (Stone and Hughes 2002a). As noted by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (2004), the closely linked terms ‘social cohesion’ and ‘community cohesion’ refer to the social ties and community commitments that bind people together. The concept of community cohesion can be defined as the interdependence and solidarity between members of a society (Berger-Schmitt 2000). The broad definition of a cohesive community set out by the United Kingdom Local Government Association (UK LGA) is one that includes: a common vision and a sense of belonging; appreciation of diversity of backgrounds and circumstances; similar life opportunities for all people not dependent on background; and a community where strong relationships can be developed between people from diverse backgrounds within workplaces and schools, as well as within the broader community (UK LGA 2003). Stone and Hughes (2002a) note that social cohesion is concerned with the connections and relationships between individuals, groups and organizations within a community. A lack of community cohesion occurs when there are divisions between social groups, individuals and systems within it, with social exclusion seen as a threat to a cohesive society (Stone and Hughes 2002a).

Closely related to the concept of community cohesion is the notion of social capital. According to the ABS, social capital “consists of networks, together with shared norms, values and understandings which facilitate cooperation within and among groups”. It is a contributor to community strength and wellbeing, and can be accumulated when people interact with one another formally and informally; for example informal interaction with family and friends and formal interaction in groups and organisations in the wider community (ABS 2004). Bridge et al. (2003:97) state that “social capital is a concept of current enquiry, research and debate…and has been defined as social connectedness from which arise norms of trust and reciprocity.” Putnam (2000:19) claims that the “core idea of social capital theory is that social networks have value.” Similarly, Bullen and Onyx (1998) note that social capital originates through the social connections and networks that people form that are based on trust, mutual interests, participation and reciprocity within the wider community thus fostering a sense of belonging. Hawtin and Kettle (2000) argue that the concept of social capital is based on the notion that societies and individuals can only achieve their potential when living and working together. An important aspect of this is the extent to which citizens can take an active part in shaping their own lives and engaging in their community.

Successful inclusionary policies, therefore, are not possible unless residents not only feel safe, secure and comfortable but also feel they belong, have ownership of what is going on, feel proud of where they live, do not feel oppressed and feel able to control their living environment (Hawtin and Kettle, 2000:122).

Although the concept of social capital is not new – it was first used by Coleman (1988) and later by Bourdieu and Wacquant (1992) – there is renewed concern regarding it as a key contributor to both the social and economic well-being of a community (Bridge et al. 2003). In Australia, Eva Cox (1995:3) highlighted the concept of social capital in the 1995 Boyer lectures where she noted:

Social capital should be the pre-eminent and most valued form of any capital as it provides the basis on which we build a truly civil society. Without our social basis we cannot be fully human. Social capital is as vital as language for human society.

|

Community Cohesion

|

Social Capital

|

|

A state of integration based on:

• interdependence

• solidarity

|

A trust resource:

• developed through social connectedness

• contributes to the building of community cohesion

|

Where there is a lack of social capital some researchers believe there is also little social and community cohesion, which in turn can lead to social exclusion. For example, the Affordable Housing National Research Consortium (AHNRC) (2001:19) notes that where there is limited community cohesion due to a lack of social capital, “segments of the community will experience social exclusion; in effect they will be prevented from full participation in the life of the community.” Social exclusion provides a framework for understanding the process of being shut out fully or partially from any of the social, economic, political or cultural systems that determine the social integration and inclusion of a person in society (Byrne 1999). The concept of social exclusion focuses on the individual, and the extent to which an individual’s experiences are exclusionary in regard to their relationships with other individuals, institutions and systems that make up communities (Stone and Hughes 2002b). Social exclusion may therefore be seen as the denial (or non-realisation) of social engagement within one’s community.

Arthurson and Jacobs (2003:i) note that in general terms “social exclusion is understood to denote a set of factors and processes that accentuate material and social deprivation”, and can be used in relation to communities as well as individuals. Nornen (cited in Vinson 2004:4) argues that the social exclusion of some communities in Australia has implications for all Australians. Social exclusion is seen to breed social alienation, and unless this is addressed in policy some Australians, along with some neighbourhoods, will continue to experience social disadvantage and exclusion. Marsh (2004) links the two concepts of social exclusion and community cohesion, claiming that exploring and addressing issues of exclusion will lead to an increase in stability within communities.

The need to develop and use community indicators to improve community cohesion and wellbeing has been identified in recent research:

Collecting indicators that measure whether people get on well together, share a common vision and sense of belonging, appreciate diversity and have strong, positive relationships are critical to understanding community cohesion (UK LGA 2003:4).

Community cohesion indicators are tools for governments and communities to use to translate broad goals into clear, tangible and commonly understood outcomes; and to assess and communicate progress in achieving these goals and outcomes (Wiseman et al. 2005). The Discussion Paper: Measuring Wellbeing, Engaging Communities (Wiseman et al. 2005:3) for example, states that “we need an integrated, long term strategy for local communities to use community indicators to improve wellbeing outcomes.” This view is reiterated in the Indicators of Community Strength in Victoria report (Strategic Policy and Research Unit 2004:7), where it is noted that “the absence of indicators can mean that important issues drop off the radar.”

Local councils in Australia are increasingly interested in indicators of community cohesion. For example, in New South Wales, Camden Council (2006) has developed five broad sustainability indicators which encompass various elements of community wellbeing. Marrickville Council, also in NSW, covers aspects of community cohesion in its ‘Belonging’ Social Plan (2004). For example, this council’s vision for the community is one where people feel safe and valued, feel a sense of pride in the cultural diversity of the area, and have a feeling of trust, cooperation and involvement in contributing to broader community affairs.

This reflects an important indicator of social wellbeing identified by Burke and Hulse (2002), namely the degree to which people see their local area as having a sense of community in terms of feeling safe and secure and feeling a part of it. Other indicators identified by Burke and Hulse include: having close friends/family living locally, having children at local schools, keeping informed of local issues, and using local parks and other services (Burke and Hulse 2002). According to Hirschfield and Bowers (1997) direct indicators of a lack of community cohesion include the inability to supervise and control teenage peer groups, the absence of local friendship and acquaintance networks, and the absence of local participation in formal and voluntary organisations; while indirect indicators include a high population turnover, social heterogeneity and low socio-economic status.

As noted in the Introduction, this research project adopted a qualitative approach which is interpretive in nature and utilises data in the form of text and phrases (Neuman 2000). As the aim of the project was to identify a common understanding of the concept of ‘community cohesion’, and to develop a set of indicators based on both the experience of residents in the targeted community and the relevant contemporary academic literature, the researchers utilised the following methods: documentary searches to review the current literature; administering questionnaires to residents; conducting focus groups with residents; and conducting interviews with key service providers.

A convergent approach was utilised in relation to the research process (Dick 2006). This process began with asking an open-ended question that had been decided previously to generate initial discussion. In all methods of data gathering, this initial question was: What do you think makes a community good to live in? This allowed respondents to answer spontaneously without any kind of prior cue. A list of probing questions was also developed so that further information could be obtained and clarified. Focus groups and interviews were then conducted, building on the earlier consultations, after the researchers had identified and reviewed key areas that needed further clarification and discussion. The results of the initial research provided insights about the central concerns of respondents, which further assisted with the direction of subsequent focus groups and interviews.

Non-probability convenience sampling was utilised to access participants for the research (Neuman 2000). Sampling took place in three ways. For the questionnaire, the researchers on three occasions and at different times of day attended a local shopping centre that could be reasonably expected to be frequented by most residents, and invited shoppers who were residents over the age of 18 to complete the questionnaires. The researchers were assisted by two Indigenous trainee staff members of the relevant local council. The trainees were part of the targeted community and their presence was designed to ensure indigenous people were included in the research. Ethical clearance for the trainees to assist was sought and given. Potential participants for the focus groups were recruited by informing the leaders of established community groups, representing a range of ages and interests, about the project. Participants for the interviews with service providers were identified through contact by the local council’s community services team.

Data was collected from December 2006 to February 2007. The study sample covered a broad cross-section of the population and included representatives from seniors and retired people, families raising children and teenagers, community organisations and clubs, and indigenous people. Specific groups are not named in order to ensure confidentiality. Other measures central to ethical research included giving a clear explanation of the research, ensuring negotiated access, and respecting human dignity and privacy (Mauthner 1998).

Questionnaires were used as they can easily be administered to a cross section of the community (Bryman 2004; Dick 2006). The questionnaires were presented face-to-face in a structured manner, thus ensuring that each respondent was asked the same questions in the same order. This is important because it ensures consistency (Bryman 2004). The questionnaires took around 15 minutes to complete. In all, 52 questionnaires were completed. A copy of the questionnaire is included as Appendix 1.

Focus groups were similarly selected for their usefulness in research exploring the experiences of a particular group or community, as they provide insights into specific areas and are an effective method of gaining a deep understanding of a situation relatively quickly (Neuman 2000). Numbers participating in the focus groups varied between 5 and 14, with a total of three focus groups held and 29 participants in all. The focus groups included a diverse sample of the target population. The groups were guided by a schedule (see Appendix 2). Answers were recorded on audiotape and notes taken to ensure accuracy (Puchta and Potter 2004). Each focus group ran for around one hour.

Three in-depth interviews were conducted with key service providers who have intimate knowledge of the targeted community. The in-depth interviews were conducted face-to-face and guided by a schedule. They each took no longer than one hour to complete. The interviews were taped and then transcribed verbatim to provide an accurate account of each interview (Minichiello et al. 1996). Consistent with approved methods of handling qualitative data (Ashton-Shaeffer 2001; Rubin and Rubin 1995), transcripts from the interviews and focus groups, along with the responses to the questionnaires, were analysed and coded with key themes identified.

This was a small study, covering just one part of a local government area. The sample size was also relatively small and not strictly representative. Further research needs to be conducted across a range of localities and local government areas to take forward the findings of this study and develop robust indicators of community cohesion. Both qualitative and quantitative approaches should be applied.

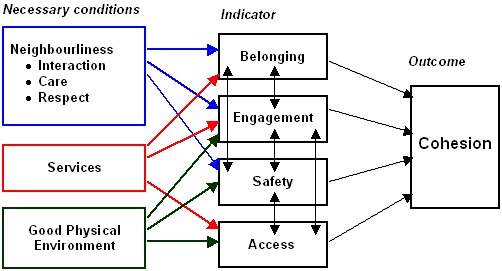

We identified four main themes woven through all types of data collected. These themes subsequently became the key indicators of community cohesion. They are: a sense of belonging; engagement; perception of safety; and access. The research further identified the conditions that are necessary in order for community cohesion to exist. These are reflected in the figure below. It can be seen that the necessary conditions feed into more than one indicator, whilst the indicators themselves are related to each other. Further research is needed to develop ways of measuring each indicator, perhaps using some of the questions from our questionnaire as a starting point.

While the study is primarily qualitative in nature, descriptive statistics can be applied to the questionnaire results, as summarised below.

• 40% of respondents had no family members living close by, 21% had only one family member nearby, and 40% had two or more relatives nearby

• Nearly 82% answered that they had friends living in the local area

• Almost 50% of respondents spoke with their neighbours frequently, while only 5% had almost no contact. Yet all felt they could ask their neighbours for help if they needed to

• 94% of respondents were aware of the services that are available in the local area.

• About half belonged to groups or clubs, and about half had attended a community event

• Approximately one third of respondents undertook voluntary work

• 86% stated that they felt like they are a part of the community.

The discussion which follows is organized according to the four themes, which are analysed in further detail and related to the literature. Some of the conditions necessary for community cohesion contribute to more than one indicator, and this overlap needs to be borne in mind. We attempt to flag where this occurs without repeating previous discussion. However, we begin our discussion with defining the concept of community cohesion as identified through participants’ responses across all three research methods.

As noted, all participants in each method were asked the same initial question: What do you think makes a community good to live in? Answers included:

• A sense of belonging, a sense of community

• Good services – including shops, schools, sports fields and parks

• Community centres/activities centres/meeting places, gatherings of people

• Supportive neighbours, knowing people

• Perception of safety

• Acceptance of, and respect for, people from diverse backgrounds

• Engaging with others in the community (both formally and informally)

• Common goals, mutual respect

• A sense of pride in the community

• Help and community support that is available in times of need.

It can be seen that these answers align closely with the literature discussed earlier. Therefore, common understandings of community cohesion appeared to reflect and confirm earlier research and could be translated into indicators. These are listed in Table 2.

Table 2: List of indicators

|

A sense of belonging - indicated by:

• Neighbourliness

o High level of interaction with neighbours, friends and

family

o An ethic of care (offering support and help)

o Mutual respect: observing boundaries, acceptance of diversity,

community consultation

• Ownership

• Sense of pride

Community engagement - indicated by:

• Volunteering

• Use of services

• Attendance at community events

A perception of safety – indicated by:

• Low official crime rate

• Residents’ expression of feeling safe

Access to resources – indicated by:

• Adequate service provision

• Built environment that promotes ease of physical mobility

• Provision for socially disadvantaged residents

|

The feeling of having a sense of belonging was a very important factor identified in relation to what makes a community good to live in. Nearly all respondents expressed some level of a sense of belonging to at least some part of the community in which they live. One of the influencing factors of a sense of belonging as noted in this study, and confirmed in other research into people’s attachment to community, is the level of integration and involvement in the local area (Cuba and Hummon 1993; Sampson, Raudenbush and Earls 1997; Soloman and Steinitz 1986). For example, Cuba and Hummon (1993) note that local social involvements, particularly those with friends and neighbours, but also those that involve family, membership of organisations and local shopping facilities and services, are evident as being the most consistent and significant sources of ties to a community. Many of these factors are discussed further in relation to community connection and engagement. The data from our research confirms this, revealing three primary factors as contributing to a sense of belonging. They are (in order of importance): neighbourliness (including the presence of family and friends), ownership, and a sense of pride.

Residents overwhelmingly cited neighbours and neighbourliness as the foundation of a strong community. This was perhaps the most striking aspect of the research. We saw that most respondents to the questionnaire had some interaction with their immediate neighbours and most could ask for some kind of help: ‘helping in times of trouble’ arose a significant number of times in the data. The research showed neighbourliness as comprising three aspects: interaction, a sense of care (offering support and help), and an ethic of mutual respect, which includes an acceptance of diversity.

Interaction can occur in formal settings, as when a person is a member of a club or committee, or it can occur informally, as in contact with family, friends and neighbours. Such contacts can range from simple greetings to more complex interactions and have been cited in the literature as important to community cohesion (Cuba and Hummon 1993; Putnam 1998). Nearly all participants knew their neighbours and most had some kind of interaction with them. Furthermore, the vast majority of respondents had friends living nearby, whilst over half had at least one family member living nearby. The fact that many participants believed they could ask their neighbours for help points to the caring aspect of neighbourliness. Keeping an eye on neighbours’ houses whilst they were away, minding children, making loans of equipment and assisting in emergencies are demonstrations of a sense of care, and these are practices that also occur between friends and family members.

However, interaction and care are not sufficient by themselves to maintain good relations between neighbours, family or friends. If there is an absence of mutual respect, relations may suffer. Respect is shown by observing certain boundaries, for example, in standards of civility and public behaviour. Negative incidents of vandalism, petty crime and violence were reported during the course of the research. It appears that in some parts of the community where we conducted our research, it is common for fences to be broken to gain access to another street. This may have something to do with the way public spaces are physically organized (see Access indicator), but it also constitutes a transgression of physical boundaries. There is also a symbolic transgression of boundaries in instances of rudeness, and it is self-evident that without mutual respect, a sense of belonging cannot flourish.

Respect is also manifested in an acceptance of diversity. The degree of diversity within the targeted locality was noted by participants in all research methods and was seen by some residents as having a negative impact on the cohesiveness of the community. Many participants identified the diversity of socio-economic status within the area, noting as one resident did: “You have the wealthy and the disadvantaged living here which can cause problems.” Another participant also spoke about disadvantage observing: “the obvious social disadvantage of some members of the community.” The UK LGA (2003) concluded that the more socio-economically diverse a community, the more likely it is to experience inter-community and inter-neighbourhood tension. Some reasons for this may be attitudinal, as in a lack of acceptance of difference, or there may be a lack of opportunity for integrating diverse groups. For example, diversity in relation to age groups was identified as an issue for some residents. One older resident mentioned being isolated within their immediate community, which comprises only older people. This means that people of diverse ages have limited opportunity and occasion to interact. Another resident was similarly concerned about prospects for interaction between different age groups, and also brought up the issue of cost, asserting: “We need to initiate contact between the kids and older residents – in the schools too. Have Grandma and Grandpa Days where the elderly come and visit the kids in school…and it doesn’t cost money.”

Diversity between generations can also impact on perceptions of safety. For example, some older people feel threatened by “groups of young people who can be quite destructive at times.” This can limit older people’s level of having a sense of belonging because they can be fearful about engaging in activities within their community (Kawachi and Kennedy 1997). Kawachi and Kennedy (1997) argue that social ties and trust within the community are weakened through social exclusion and disadvantage, which can become one factor in committing crime. This concern is addressed further in the discussion related to perception of safety with the community. However, at this point we have attempted to establish that intolerance as shown by a lack of acceptance of diversity is a form of disrespect which mitigates against neighbourliness.

A sense of ownership emerged as crucial to sense of belonging to a given community. This was cited by many of the participants as being a key factor in promoting community cohesion: “The community needs to have a sense of ownership.”

One service provider pointed out that for that section of the population who live in public housing, there is little choice in where they live and very little chance of ever acquiring their own homes. Ownership gives one a stake in a locality and provides a motivation for establishing good relationships (Bridge et al. 2003). The research showed that a sense of ownership is not necessarily contingent upon private property rights, but can also be fostered by having a choice about where one lives, and by being consulted about issues that directly affect residents. Members in each of the focus groups commented on the need for the local council to involve residents more in decision-making. By being consulted, people are given a sense of ownership of a project and in turn feel pride in what they have accomplished. This pride then flows over into the community.

Indeed, a feeling of pride was named by respondents in all research methods as part of what defines a good community. Pride can only be felt in relation to something one feels a part of, and therefore it is an important ingredient of a sense of belonging. An example of how ownership and pride can enhance community cohesion was found at one of the sporting clubs, where young people were involved in the refurbishing and painting of the toilet facilities, which had been consistently vandalized for a long period. One participant said: “They painted it all up – put a mural on it and it hasn’t been touched since. It’s given them a sense of ownership.”

We found that most participants cited involvement in community life as essential to community cohesion. Engagement can include three distinct factors: volunteering, using services and attending events. We found that volunteering was most commonly seen as promoting social bonds through service and membership of groups such as clubs. Although not all residents who participated in this study were involved formally in clubs and groups, they were engaged in the community in informal ways. This is particularly evident in the responses to the questionnaires, which asked whether residents know their neighbours. The majority not only knew their neighbours, they also had close and frequent contact with at least one of them. This data would therefore signify that even if residents were not members of a formal sporting club or group (about half were), or not involved in official voluntary work (around one third volunteer in an official capacity), they are still connected to, and involved in supporting their community at an informal level. This aligns well with the literature. For instance, Putnam (1998) distinguishes between formal and informal social networks with formal ties including those with voluntary organisations and informal ones being those of family, friends and neighbours. These informal networks can be identified and measured by how often friends and neighbours are visited, as well as through belonging and participating in groups and clubs (Baum et al. 2000).

As noted above, many residents do engage in formal activities such as volunteering which can contribute to engagement with one’s community. One resident pointed out: “People who contribute to their community through volunteering tend to be the ones who are most engaged.” As noted by ABS (2002, p.13): “volunteering may be seen as an expression of reciprocity or potentially as a direct outcome of social capital. The act of volunteering demonstrates a balance between individuals’ self interest and public interest.” Volunteering can also assist in breaking down barriers between diverse groups within a community, which in turn can contribute to community cohesion in terms of belonging and mutual respect. One resident identified this issue when explaining why they like to volunteer: “You get to meet a cross section of the community.” Indeed, in this study volunteering was seen as a key determinant in indicating a strong community. For example, one participant pointed out: “Maybe that’s actually a barometer of how healthy the community is or how it engages – in how people feel about giving up their time to volunteer.” Another said: “When people volunteer they often find out that it’s a good way to engage – through their kids – and they get to know more about their community.”

Some participants had concerns about the concept of volunteerism with one noting: “I don’t think that volunteerism should take the place of a paid position”; further commenting that: “volunteers need to be well supported.” This signals an element of cynicism in the community. Some participants are aware that the discourse of community cohesion can be used by central governments to legitimise cost cutting in the name of handing back control to the grass roots level.

The uptake of services and attendance at community events feeds into both belonging and engagement by providing residents with opportunities to come together, interact and participate. The shopping centres were the most widely used service, but other services that were significant included health services (community health, early childhood, dental and medical services), sporting facilities, clubs, parks, schools, the library, walking paths and transport. Services which were not available but identified as needed were a youth centre, a swimming pool, better transport, policing, meeting places and services for young children.

Half of the respondents to the questionnaire had attended a community event in the last year. The events cited were a community BBQ, a residents’ Christmas party, sports events and events for seniors. Those who did not attend gave reasons such as being too busy, being unaware of the event, or that the event was not relevant to their interests or age group. It would thus seem that a range of well-publicised events that appeal to the various social groups could help to promote engagement.

Importantly, the research confirmed that having a level of community connection was a major factor in of perceptions of safety (Haigh 2006).

For the older residents in this study, especially, a sense of safety was of particular significance. Some older people spoke about not feeling safe in their homes, with several telling of their experiences of intruders and incidents of burglaries and theft. One older resident believed that: “Thieving and vandalism are the biggest problems in our community.” Another older resident asserted: “Whatever’s not bolted to the ground gets stolen.”

However, it was not only older residents who were concerned with safety. This was a key issue identified in all of the focus groups and raised by many of the residents in the questionnaires, as well as in the in-depth interviews. For example, one resident in a focus group said: “I wouldn’t go out walking after dark.” This comment led to all-round agreement from the other participants: “Yes, safety of a night is an issue.” More lighting was one solution identified as being needed to help address issues of safety.

If people do not feel safe in their home, this has consequences on a larger scale. For example, this can impact on the level of a person’s engagement with their community because, as explained by one participant: “If you’re sitting in your house and you’re really fearful it’s unlikely that you’re going to engage with the community.” Another participant explained the connection between their immediate living environment and the wider community this way: “Some people are fearful about where they are living and that impacts upon their perceptions of the community.”

It seems clear that a low rate of crime might be a partial measure of a sense of safety. Many residents were concerned that crime was on the increase, with some suggesting ways to address crime. These focused chiefly on a greater police presence in the area. Apart from official policing, suggestions included installing security cameras in key areas such as shopping centres and sporting clubs, or community-based projects such as Neighbourhood Watch. This is consistent with other research into crime reduction within communities. For example, according to Graycar (1999) two key features of crime prevention are: involving community members in projects and committees (engagement), and the creation of opportunities to enable all members to live, work and socialise – to participate – without feeling threatened or being harassed (mutual respect).

Community connection not only needs to include reducing perceptions of fear of crime through community involvement, but also overcoming the isolation of some individuals. To this end, accessible neighbourhoods and communities have been identified as important for a cohesive community (Haigh 2006). In this project, residents identified access as being of key importance, particularly in relation to the provision of services, but also in terms of having the material means to access these services.

Most residents are aware of services that are currently available in the targeted community. However, as noted by some participants, accessing these services can be problematic if they do not have their own transport, especially at night and on weekends. One participant said: “I think there’s enough in the way of services, but accessibility is another story. There’s not enough buses for one thing.” This in turn impacts on people’s sense of engagement within the community and can add to feelings of isolation. Transport impacts on people’s quality of life by allowing people to access employment and education opportunities, services, recreational facilities and other social networks (Haigh 2006). For example, one participant noted: “Transport is a big issue. A lot of people have a feeling of being stuck and confined.” This has particular relevance to certain groups such as young people, older people and socially disadvantaged people, many of whom are without private transport.

Other issues can also impact on people’s ability to access services and activities in the community. For example, good footpaths were identified in relation to access to parks, services and facilities. This was seen as being important especially for parents of young children using prams and strollers, and for older residents. One resident suggested a bicycle path would be “useful for all ages.”

The built environment is also relevant to issues of respect for boundaries and safety (Haigh 2006). One example raised in the research was the design of housing estates. In this study, residents identified one particular area where the ‘poor design’ was seen as leading to “the attitude where some people would just walk through other people’s places when they feel like it to get somewhere and it’s contributed to people feeling unsafe.” A participant explained: “People have to walk through backyards to get to another property and they were taking fence posts out. And that was leading to major vandalism and crime issues for people who lived in an adjoining street.” Another participant spoke about “pulling palings from fences” when talking about problems with people walking through property as a short cut. This has led to a feeling of being unsafe: “You have to keep the doors and windows locked because people just walk through.”

Issues that relate to the built environment can thus draw together concerns in relation to access, mobility, respect for boundaries and perceptions of safety within a community. The design of the built environment can also add to people feeling closed in and isolated from other members of the community. As one resident explained: “There’s only one road in and out…[and] to some extent it’s felt that because there’s only one way in that it’s sort of closed in.”

Green space was another aspect of the built environment that was considered important for a cohesive community, with design being identified as central. As one participant said: “…it has to be ‘good’ green space.” One specific local park was identified as being well used. A resident commented: “I think one of the things that is used well in the community is the Park.” Another said: “The Park is a meeting place. My teenagers walk up there to play basketball and they’re always safe.” Once again the recognition of the importance of meeting places to a community in fostering a sense of belonging is evident. It is clear that much informal engagement is taking place within the community’s green spaces.

People in receipt of lower than average median weekly household incomes said that participation in some activities was problematic. For example, one resident noted: “With sport it can cost between $65 and $150 to join up and then there’s all the equipment and some people can’t afford it.” Issues of social inequality concerned residents. This was particularly evident when discussing costs of accessing activities and services. Another resident when commenting on the cost of participating in sport and other activities said: “We need free things to do – free things are important.” More broadly, the following comment tied socio-economic diversity to ‘free things’: “Free things to do goes back to the broad difference of the socio-economic difference of people living here. The ones that use the free facilities are the ones that can’t afford to have their own pool, for instance. Or the ones that can’t go down town because they don’t have transport.”.

One resident, when speaking about social disadvantage, identified the lack of choice that some residents face: “Some people have made the choice to live here but there are those who don’t have a choice. A lot of people who are socially disadvantaged haven’t got the choices - they didn’t choose to live here. So we need to provide financial assistance so they can participate in sport and these sorts of things.”

Clearly, accessibility of services in terms of cost and choice is particularly important for socio-economically disadvantaged people. Being able to take part in activities can impact on the level of community involvement (or engagement) in general, which in turn has been identified as key to sense of belonging (Byrne 1999).

The indicators of community cohesion that we identified highlight a number of factors, namely, neighbourliness, the provision of services, and a good physical environment, and these are deeply interdependent. For example, access is important in its own right, but it also contributes to a perception of safety (particularly in terms of the built environment and urban design) and assists in promoting engagement. This is an area that needs further research to elicit the specific links between access factors and cohesion. A sense of belonging has a reciprocal relationship with engagement: engagement helps to foster a sense of belonging, whilst belonging motivates engagement behaviours. These findings were broadly consistent with the established literature on community cohesion, which lends a dimension of validity to the research. Local government authorities and service providers are doubtless already aware of many of these issues. However, there is a need to formalise and conceptually map the relationships between the various elements which together comprise social cohesion. This, it is hoped, will assist such bodies in the design and implementation of policies and initiatives which can strengthen the ‘social glue’ that binds potentially fragile communities together.

We have seen that there are both formal and informal elements that make for social cohesion. Though local councils and services providers can address the more formal components, they cannot control informal social processes. This is particularly relevant to the indicator of neighbourliness. There is, for example, a degree of randomness in who becomes one’s neighbours – mostly they cannot be chosen. The way that such relationships are formed and the manner in which they develop is informal and organic in nature, and therefore largely beyond the influence of other parties.

The most significant finding was that participants overwhelmingly named neighbourliness as the most important aspect of a strong community. Yet, whilst it is central, neighbourliness does not mean excessive familiarity or the taking of liberties. A key part of neighbourliness involves respecting each other’s boundaries and this includes a respect for diversity. The promotion of an environment conducive to achieving this sort of balance must be the primary object of strategies aimed at promoting community cohesion.

We wish to express our grateful thanks and appreciation to our reviewers who gave invaluable feedback and suggestions which strengthened this paper.

ABS [Australian Bureau of Statistics], 2001. Census of Population and Housing, Census Data, Canberra.

ABS [Australian Bureau of Statistics], 2002. Social Capital and Social Wellbeing, Discussion Paper, August.

ABS [Australian Bureau of Statistics], 2004. Measuring Social Capital, Canberra, Cat. No. 1378.0.

AHNRC [Affordable Housing National Research Consortium], 2001. Affordable Housing in Australia: Pressing Need, Effective Solution, Working Paper, pp.1-38.

Arthurson, K. and K. Jacobs, 2003. Social Exclusion and Housing, Final Report, AHURI [Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute], pp. 1-32.

Ashton-Shaeffer, C. 2001. ‘Thematic Networks: An analytic Tool for Qualitative Research’, Qualitative Research, vol. 1(3), pp. 385-405.

Baum, F., Palmer, C., Modra, C., Murray, C. and R. Bush, 2000. ‘Families, Social Capital and Health’, in I. Winter (ed.), Social Capital and Public Policy in Australia, Australian Institute of Family Studies, Melbourne, pp. 250-275.

Berger-Schmitt, R. 2000. Social Cohesion as an Aspect of the Quality of Societies, EuReporting Working Paper No. 14, Centre for Survey Research and Methodology, Mannheim.

Bilton, T., Bonnett, K., Jones, P., Skinner, D., Stanworth, M. and A. Webster, 1997. Introductory Sociology, Palgrave Macmillan, Houndmills.

Bourdieu, P. and L. Wacquant, 1992. An Invitation to Reflexive Sociology, University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Bridge, C., Flatau, P., Whelan, S., Wood, G. and J. Yates, 2003. Housing Assistance and Non-Shelter Outcomes, Final Report, AHURI [Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute], pp. 1-184.

Bryman, A. 2004. Social Research Methods, 2nd edn., Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Bullen, P. and J. Onyx, 1998. Measuring Social Capital in Five Communities in NSW, CACOM, University of Sydney.

Burke, T. and K. Hulse, 2002. Sole Parents, Social Wellbeing and Housing Assistance, Final Report, AHURI [Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute], pp. 1-45.

Byrne, D.S. 1999. Social Exclusion, Open Press University, Philadelphia.

Cabinet Office Third Sector, 2008. Public Service Agreement Framework, viewed 24 October 2008,

<http://www.cabinetoffice.gov.uk/third_sector/Partnership_working/public_service .aspx> .

Camden Council, 2006. Sustainability Indicators, Camden, NSW.

Coleman, J. 1988. ‘Social Capital in the Creation of Human Capital’, American Journal of Sociology, vol. 94, pp. 95-120.

Coutts, A., Pinto, P.R., Cave, B. and I. Kawachi, 2007. Social Capital Indicators in the UK, Commission for Racial Equality, London.

Cox, E. 1995. A Truly Civil Society, 1995 Boyer Lectures, Australian Broadcasting Commission, Sydney.

Cuba, L. and D. Hummon, 1993. ‘A Place to Call Home: Identification with Dwelling, Community and Region’, The Sociological Quarterly, vol. 34(1), pp. 111-131.

Dick, B. 2006. Action Research Resources: Community Consultation, University of Queensland.

Giddens, A. 1984. The Constitution of Society, Polity Press, Cambridge.

Graycar, A. 1999. ‘Crime and Social Capital’, 19th Biennial International Conference on Preventing Crime, Melbourne.

Haigh, Y. 2006. Promoting Safer Communities through Physical Design, Social Inclusion and Crime Prevention through Environmental Design: A Developmental Study, Centre for Social and Community Research, Perth.

Haraway, D.J. 1991. ‘Situated knowledges: The science question in feminism and the privilege of partial perspective’, in Simians, Cyborgs, and Women: the Reinvention of Nature, Routledge, New York.

Harkness, J. and S. Newman, 2003. ‘Effects of Home Ownership on Children: The Role of Neighbourhood Characteristics and Family Income’, Economic Policy Review, vol. 9(2), pp. 87-107.

Hawtin, M. and J. Kettle, 2000 ‘Housing and Social Exclusion’, in J. Percy-Smith (ed.), Policy Responses to Social Exclusion: Towards Inclusion?, Open University Press, Buckingham.

Hirschfield, A. and K. Bowers, 1997. ‘The Effect of Social Cohesion on Levels of Recorded Crime in Disadvantaged Areas’, Urban Studies, vol. 34(8), pp. 1275-1295.

Home Office Community Cohesion Unit, 2003. Building a Picture of Community Cohesion, London.

Hunt, E. and D. Colander, 1996. Social Science: An Introduction to the Study of Society, 9th edn., Allyn and Bacon, Boston.

Kawachi, I. and B. Kennedy, 1997. ‘Health and Social Cohesion: Why Care about Income Inequality?’, British Medical Journal, vol. 314, pp. 1037-1040.

Marrickville Council, 2004. Belonging in Marrickville, Marrickville, NSW.

Marsh, A. 2004. ‘Housing and the Social Exclusion Agenda in England’, Australian Journal of Social Issues, vol. 39(1), pp. 7-22.

Mauthner, M. 1998. ‘Bringing Silent Voices into a Public Discourse: Researching Accounts of Sister Relationships’, in J. Ribbens and R. Edwards (eds), Feminist Dilemmas in Qualitative Research: Public Knowledge and Private Lives, Sage Publications, London.

Minichiello, V., Aroni, R., Timewell, E. and L. Alexander, 1996. In-depth Interviewing, Macmillan, Melbourne.

Neuman, W. 2000. Social Research Methods: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches. 3rd edn., Allyn and Bacon, Boston.

Nevile, A. 2003. State of the Family 2003, Anglicare Discussion Paper, pp.1-54.

Puchta, C. and J. Potter, 2004. Focus Group Practice, Sage Publications, London.

Putnam, R. 1998. ‘Foreword’, in Housing Policy Debate, vol. 9(1), pp. v-viii.

Putnam, R. 2000. Bowling Alone, Simon and Schuster, New York.

Rubin, H. and I. Rubin, 1995. Qualitative Interviewing: The Art of Hearing Data, Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA.

Sampson, R., Raudenbush, S. and F. Earls, 1997. ‘Neighbourhoods and Violent Crime: A Multilevel Study of Collective Efficacy’, Science, vol. 277, pp. 918-923.

Solomon, E. and V. Steinitz, 1986. Starting Out: Class and Community in the Lives of Working-class Youth, Temple University Press, Philadelphia.

Stone, W. and J. Hughes, 2002a. ‘Understanding Community Strengths’, Family Matters, vol. 61, pp. 62-68.

Stone, W. and J. Hughes, 2002b. Social Capital: Empirical Meaning and Measurement Validity, Research Paper No. 27, Australian Institute of Family Studies, pp. 1-70.

Strategic Policy and Research Unit, 2004. Indicators of Community Strength in Victoria, Department for Victorian Services.

UKLGA [United Kingdom Local Government Association], 2003. Guidance on Community Cohesion for Local Authorities.

Vinson, T. 2004. Unequal in Life, Jesuit Social Services, Richmond, Victoria.

Waters, A. 2001. Do Housing Conditions Impact on Health Inequalities Between Australia’s Rich and Poor?, Final Report, AHURI [Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute].

Wiseman, J., Langworthy, A., Salvaris, M., Heine, W., McLean, N. and J. Pyke, 2006. Measuring Wellbeing, Engaging Communities, Institute of Community Engagement and Policy Alternatives (ICEPA), Victoria University, the VicHealth Centre for the Promotion of Mental Health and Social Well Being, School of Population Health, University of Melbourne and the Centre for Regional Development, Swinburne University of Technology.

Community Cohesion Questionnaire

1) What do you think makes a community good to live in?

2) What sorts of things make you feel safe in your community?

3) How many of your family members not living with you live in (this suburb)?

4) Do many of your friends live in (this suburb)?

5) Do you know your neighbours

5a) If yes, how often would you talk to your neighbours?

6) Can you ask your neighbours for help?

6a) If yes, what kind of help?

6b) If not, why not?

7) Do you know what services are available in (this suburb)?

eg: education; transport; facilities such as parks, playing fields, meeting places; health services such as baby health centres; shops; support services such as community visiting schemes etc.

8) Which services do you use?

8a) What services do you think are most needed in (this suburb)?

9) Do you belong to any community groups or clubs?

9a) If yes, which ones?

10) Have you attended a community event in (this suburb) in the last year?

10a) If yes, which ones?

10 b) If not, why not?

11) Do you do any voluntary work in (this suburb)?

11a) If yes, what kind?

12) Do you feel like you are a part of the community?

12a) Why?

12b) Why not?

13) How long have you lived in (this suburb)?

14) How many people live in your household?

15) Any other comments?

Appendix 2

Interview Guide (Focus groups and in-depth interviews)

• What do you think the word ‘community’ means?

• What do you think makes a community good to live in?

• How important is a sense of safety to community cohesion?

• How important is the built environment?

• What do you think makes a community feel like home?

• How important do you think services and programmes are in fostering a sense of community cohesion? Why?

• What services do you think are most needed in (this suburb)?

• How important do you think membership of community groups or clubs is to community cohesion?

• How important do you think voluntary work to a sense of community cohesion?

• Any other comments?

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/ComJlLocGov/2009/6.html