|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

Western Australian Law Teachers' Review |

INCORPORATING VISUAL LEARNING AIDS IN TEACHING LAW

NATALIE BROWN *

I INTRODUCTION

Prior to teaching law as a casual tutor and later as a full-time lecturer, I enjoyed previous career incarnations as a commercial artist and a literacy aide in a primary school. During my stint as a literacy aide it was natural to use my abilities to create visual learning aids for students who struggled with written and oral learning, such as cartoons, diagrams or illustrated stories for specific learning needs. I found that visual methods assisted breaking down psychological barriers by building student confidence in their own capacity to learn. When I commenced tertiary teaching, I modified these tools and incorporated them into my tertiary teaching pedagogy without really considering why or how it worked. I knew it helped me because I had used visual aids as a law student: mind-maps or flow-charts for legal concepts or illustrating connections between principles in an entire unit; or what I referred to as case illustrations, a simple picture to trigger the case facts. As a tutor my whiteboards were filled with cartoons, illustrations, and mind-maps because it had helped me, and student feedback confirmed it helped others also. Encouraged by the feedback, I continued to refine my visual learning techniques. It was a natural progression to incorporate this teaching style into my lecture slides as a lecturer. Fear not, you do not need to have any artistic ability to engage with visual learning — in fact some of my poor attempts at illustration on the whiteboard have injected much-needed humour into otherwise potentially dry explanations.

II WHY VISUAL LEARNING WORKS

For me, including this methodology in my tertiary law teaching was an organic process because it worked for me as student and during my previous teaching experience, rather than it being a well-researched choice to develop my teaching pedagogy. However, I was not surprised to find there were many teachers — before I even thought about teaching — who had explored and written on the subject.[1] I was heartened to see that not only did other teachers see the benefit, but it was also backed up by science. The literature on visual learning is mostly aimed at primary and high school education but it is equally applicable at a tertiary level.

Visual learning is not an entirely accurate term, it is perhaps better described as multi-sensory learning or dual-coding that engages both sides of the brain — for example, an image, and explanation and an example for context.[2] Our preferred learning style will depend on which side of our brain is dominant, the left-side is the seat of language and processes logically, and the right side processes intuitively.[3] Right side dominant thinkers are sequential, vertical, or convergent (aural or auditory learners) and left side dominant thinkers are spatial, non-lineal, lateral or divergent (visual learners).[4] Both sides of the brain are engaged in nearly every human activity.[5]

Our dominant side is a preference not an absolute.[6] Developing both learning styles can help us learn more effectively.[7] Early literature identified that law students who were poor organisers (left side dominant) were assisted by visual representations that provided conceptual patterns to aid analysis.[8] Visual tools assists students who find aural and written material more challenging (left side dominant), and augments auditory sequential learners (ride side dominant) by strengthening less-used neural pathways so they become more flexible thinkers.[9]

Visual learning develops visual thinking — ie, the capacity to retain and understand information by association ideas, words and concepts with images —[10] which in turn develops our visual literacy (the ability to create visual instruction).[11] Comic strips as a means of explaining contracts are gaining traction so visual literacy may soon become not only a tool for students, but a useful skill for practicing lawyers.[12] During a tutorial I once set a group task of developing a mind-map to illustrate a case principle. A majority of students appeared to find that task very difficult, however, exposure to visual teaching will improve students’ visual literacy. By the end of the semester many of my students create their own task-specific visual aids based on the examples they see in tutorials and lectures.

One of the reasons visual learning works is because it reflects our cognitive thinking process in the hippocampus — this is the part of our brain that stores memory and solves problems, and does not operate by archiving word documents, but by recognising and developing cognitive maps.[13] Visual aids allow the brain to do what it does best: find patterns, identify gaps, make associations and play with the pieces of the jigsaw puzzle.[14] This is demonstrated in a study by Raiyn, which considered the development of higher-order thinking skills necessary for problem based learning (ie, analytical or critical thinking skills consisting of selecting, ordering, comparing and evaluating; and creative thinking consisting of problem finding, efficiency, flexibility, originality and elaboration).[15] Raiyn’s study found that these higher-order thinking skills were better in students who engaged in visual learning as opposed to traditional methods.[16] A concrete visual image is more easily remembered than an abstract word. For example, if you are required to remember the words dog, bike and street in sequence, it is easier to retain the sequence for longer if we add a visual (eg, the dog got on the bike and rode down the street) compared to repeating the sequence ten times and then trying to recall it a week later.[17]

Why does it stick? It is not entirely about the visual representation but also about the cue we receive with the image. For example, without reading the cue at footnote number 18, try to interpret the image at Figure 1.

Figure 1. Image to demonstrate the power of visual cues.

Note: This image is reproduced with express permission from its creators.[18]

To most the image appears to be grey and black regions and it is hard to categorise without an additional cue. Once you receive the cue it will be hard to see the image without your brain immediately adding the cue, even months later.

In the following section, I provide examples of the visual aids I commonly use, mind-maps or flowcharts and illustrations, but visual learning aids can include symbols, video games, films, graphs, posters, board games or flashcards,[19] the only limit is your imagination.

III INCORPORATING VISUAL LEARNING IN THE TEACHING OF LAW

This Part presents just a few examples of the many illustrations I use in teaching Property Law. Illustrations are useful to demonstrate the facts of case, and this visual cue can be followed by the facts in writing (which is what I usually do). It allows students to focus on what you are saying rather than try to read the facts, and it also allows the student to easily find the case when reviewing the slides. If you enjoy illustrating, you can incorporate a cartoon, but a compilation of images can be used instead.

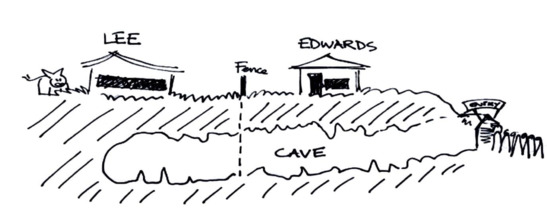

For example, Figure 2 is a fact illustration for a case about subsurface rights. The cave extended from the defendant’s land onto the plaintiff’s land, but only had one entrance (on the defendant’s land). The defendant was profiting from the cave by charging an entry fee, and the issue was whether the defendant was trespassing on the plaintiff’s land.

Figure 2. Image drawn by the author and used in lecture slides to demonstrate the facts of the case Edwards v Sims (1929) 24 SW (2nd) 619 (Ken CA).

Another example I use in lecture slides relates to Davies v Bennison [1927] Tas LR 52, in which the defendant neighbour argued there was no trespass because the offending bullet was not on his neighbour’s land, it was imbedded in the cat. In my slides I have inserted the following cartoon-like images: a man with a firearm; a bullet; a cat sitting on a roof; and a cat that has fallen off the roof. I use arrows to connect these individual pictures, showing the journey of the bullet from the gun, to the cat on the roof, and then to the dead cat that has fallen off the roof. It would also be possible to use PowerPoint to animate the scene for extra impact — eg, by shooting the bullet.

Mind-maps are also helpful. The development of mind-maps takes time, and I continually adjust and refine my mind-maps. Mind-maps can be used to illustrate case principles or broad concepts, I use both hand drawn mind-maps and those I construct using a word processor.

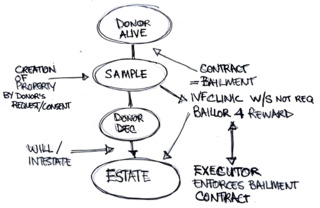

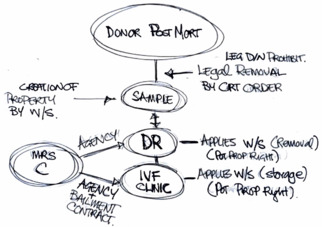

The mind-maps shown at Figure 3 and Figure 4 illustrate the case principle in a tutorial problem that discusses rights to sperm samples (including the different principles that apply depending on whether the sample is created while the donor is alive, or whether the sample is extracted from the donor post-mortem). As shown in Figure 3, when the donor is alive they can create property from their body by separating the sample (eg, by cutting off their hair and selling to a wigmaker) in this instance, on the donor’s death the property falls into their estate. But as shown in Figure 4, a post-mortem donor cannot create property — the property is created by the work and skill of the doctor acting as an agent for the donor’s partner.

Figure 3. Mind-map showing the principles relating to a sperm sample from a live donor.

Figure 4. Mind-map showing the principles relating to a sperm sample from a dead donor.

Mind-maps like these can be illustrated on the whiteboard during tutorial teaching or can be constructed using a word processer to add to lecture slides or topic outlines.

IV CONCLUSION

At first, it may seem that law as a language-based discipline is not amenable to graphs and charts or other visual aids, which are normally seen in science disciplines. However, visual aids are an excellent tool to explain otherwise difficult concepts and their use has been successfully explored as a means of explaining the law to laypersons.[20]

Seeing is a process that affects our other sensory perceptions. The old adage says ‘we eat with our eyes’, meaning something will taste better if it looks appetising. For sighted people, our sense of taste is affected by what we see — if we are blindfolded and eat something, it is much harder to identify what we are tasting because we are not receiving the visual cue. Similarly, a visual cue can help us understand better. So, when teaching, consider providing a visual cue to the word-based explanation, or vice versa, a visual explanation with word-based cues. In doing so, it is important to ensure that learners who are blind, have low vision, or are otherwise vision-impaired need to be given the same learning opportunities as their sighted peers. Accordingly, anything shown in images should always be explained adequately in class.

It is time consuming to create high quality visual learning mind-maps, diagrams, and illustrations. However, the work is worth the effort. I find it not only improves student learning, but it also improves my teaching because of the thought I have had to apply to create a visual aid that has clarity and illustrates the principle. The research suggests that these experiences are not merely anecdotal or perceived, but are grounded in reality.

* Natalie Brown is a Lecturer at the UWA Law School, The University of Western Australia.

[1] William Wesley Patton, ‘Opening Students Eyes: Visual Learning Theory in the Socratic Classroom’ (1991) 15(1) Law and Psychology Review 1.

[2] Jesse Berg, Visual Leap, A Step-by-Step Guide to Visual Learning for Teachers and Students (2015, Taylor and Francis) 20–1, 29–30.

[3] Riad Asani, ‘Learning Styles and Visual Literacy For Learning And Performance’ (2015) 176 Social and Behavioural Sciences 538, 540.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[10] Jamal Raiyn, ‘The Role of Visual Learning in Improving Students’ High Order Thinking Skills’ (2016) 7(24) Journal of Education and Practice 115, 115.

[11] Asani (n 3) 544; Michael D Murray, ‘Cartoon Contracts and Proactive Visualization of Law’ (2021) 16 University of Massachusetts Law Review 98, 101, 112–13.

[12] Murray (n 11) 102–114. See example of a comic strip contract at 101 of this source.

[15] Raiyn (n 10) 115. See also Asani (n 3) 542.

[18] The image is of a bearded man. Image sourced from Mariv Ahissar and Shaul Hochstein, ‘The Reverse Hierarchy Theory of Visual Perceptual Learning’ (2004) 8(10) Trends in Cognitive Sciences 457, 457–8. You can see a visual cue at <www.cs.princeton.edu/courses/archive/spring08/cos598B/Readings/AhissarHochstein_TCS2004.pdf>. Permission for reproduction of the image obtained from Mariv Ahissar via email on 7 February 2024.

[19] Asani (n 3) 541; Raiyn (n 10) 115. For an example of boardgame designed specifically for law see Patton (n 1) 8–10. For discourse on creating different types of flowcharts and mind maps see Berg (n 2) ch 11.

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/WALawTRw/2024/7.html