|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

Western Australian Law Teachers' Review |

WHAT MAKES A GREAT HDR SUPERVISOR IN LAW? PERCEPTIONS FROM HDR STUDENTS AND THEIR SUPERVISORS

JADE LINDLEY, NATALIE BROWN AND LIAM QUINN *

I INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND

The relationship between a supervisor and a Higher Degree by Research (HDR) candidate for a Master’s degree by Research, Doctor of Juridical Science (SJD), or Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) qualification can contribute to the candidate’s timely submission of their thesis. The 2020 article by Lindley, Skead and Montalto,[1] identified this complex relationship as a contributing factor to HDR students’ completion or attrition.[2] The present study builds on those research findings by exploring the characteristics of the supervisory relationship that HDR students and supervisors identify as key to successful thesis completion. The results presented in this article intend to assist HDR supervisions in law.

Students’ socio-psychological wellbeing (also referred to simply as wellbeing) is a complex phenomenon that requires further research in the HDR context.[3] The students’ wellbeing is key to completing the intellectually and emotionally challenging HDR journey and their success thereafter.[4] The personal aspects of the supervisory relationship can impact positively or negatively on the timely completion of the research project. A supportive supervision relationship is a vital component of the PhD journey.[5] Emotional support is equally as important as academic guidance to develop a constructive relationship and the students’ self-confidence.[6] A healthy mentor relationship is a critical factor contributing to completion rates,[7] because students are insulated within supervisory relationship, which will be a source of resilience or a risk to the students’ well-being.[8] Stress, exhaustion, anxiety, and lack of interest (or socio-psychological ill-being) may lead to attrition.[9] Students who have a positive HDR experience may be ‘empowered’ whereas those who have a negative HDR experience may feel ‘burdened’ and experience exhaustion, insecurity and anxiety.[10] Students experiencing good wellbeing frequently cite feelings of satisfaction, support of learning, inspiration, and engagement.[11] High quality supervision is an important contributing factor to the development and fostering of students’ wellbeing.[12] We submit that the quality of support provided by supervisors in this relationship is key to optimising supervision, as well as empowering and inspiring the student during the supervision process leading towards thesis completion.

Looking specifically at the PhD journey across any discipline, the supervisory relationship is long; three years full-time at a minimum, and often closer to four or five years. The supervisory relationship is even longer if the candidate is completing the research project part-time. As a side note, many of us have embarked on this relationship with little consideration of whether the personalities and skills of the supervisor and candidate are a good fit that will complement each other, or develop positively over the long term, and ultimately, contribute positively to PhD completion. Supervisors and candidates are paired often for academic reasons and may potentially know each other as colleagues or past students or other association,[13] the compatibility of personalities is an aspect often not discovered until well into the period of supervision. Therefore, the success of a supervisory relationship must depend on the characteristics of the supervisor and the candidate, what the parties consider important, whether each deliver on expectations, and when conflicts arise, whether the parties have the skills to resolve disputes, enabling the relationship to continue.

The parties’ relationship in law HDR supervisions may have a greater impact on the candidate’s success in comparison to other disciplines, such as sciences, due to the nature of the research. For example, laboratory based empirical research differs from legal research that is largely desk-based and oftentimes doctrinal.[14] Specifically, research suggests completion times are often quicker and more collaborative in science-based disciplines than language-based disciplines,[15] leading to correlatively, lower attrition rates than disciplines such as law.[16] Despite an upward trend in other methods as aside from purely doctrinal in law, doctrinal researchers are likely to experience greater isolation than collaborative laboratory-based researchers,[17] and are more likely to engage the subjective opinions of the supervisor and student,[18] than HDR students in the sciences. These circumstances in law make the student/supervisor relationship all the more important to maintain the student’s wellbeing.

Some aspects of the supervisory role that may be important in the early research phases, may be less important during the final push to refine the finished thesis. For example, timely feedback, encouragement, support, empathy, and assistance refining the research task may be more important to the candidate’s achievement during the early stages of the project, while attention to detail is a relationship quality that is more useful for the finalisation of the research task. Indeed, a supervisor who has completed a PhD themselves may bring empathetic qualities to supervision because they understand the early research challenges and can support the candidate by normalising common issues and setbacks through shared experience.[19]

The initial choice of supervisors and acceptance of candidates is primarily based on academic acumen, appropriate knowledge and skills, and a shared interest in the research task.[20] Students rank competence and warmth as important qualities of a HDR supervisor, however, interpersonal skills are not attributes that can as easily be ascertained as competence during this important decision-making process.[21] Supervisors and HDR students may have had pre-existing association or students may reach out to a potential supervisor based on their research profile reputation or advice from other students.[22] However, the needs of individual students are not homogenous,[23] the supervisor’s personality that worked well for one student may not work for another.[24] Largely many characteristics that will contribute to an optimal PhD supervision are unknown and unknowable until the relationship commences in earnest.

To understand and identify the important characteristics of the supervisory relationship and contribute to successful and timely completion of law HDR theses, we conducted empirical research by surveying current and retired HDR supervisors, and current students and those who had completed, a PhD or SJD at the University of Western Australia (UWA) Law School in the five years prior. This article addresses the knowledge gap identified by Lindley, Skead and Montalto by answering the question, what relationship characteristics contribute to optimal PhD supervision? This article answers that question in the following sections: the methodology that describes the empirical approach undertaken; followed by the results of the perceptions surveys; and lastly, the discussion drawing on results and literature findings; and the conclusion. The intention of the research is to confirm, through empirical findings, expectations to support HDR supervision at the institutional and personal levels to benefit both students and supervisors. Key findings indicate the need for enhanced continuing professional development (CPD) for supervisors, in particular, conflict resolution and interpersonal skills. We suggest that cross institutional access to supervision CPD could address this deficit. The aim of this article is to provide a foundation of understanding that will both support students and supervisors, and supporting institutions to identify factors that lead to attrition and develop tools and resources to achieve optimal PhD supervisions.

II METHOD

Two voluntary and anonymous surveys were developed on the online survey platform, ‘Qualtrics’. Ethics approval was granted for the research project on 15 November 2021, by the UWA Human Research Ethics Office (REF: 2021/ET000682). The surveys were active for completion from 26 November 2021 to 21 December 2021, during the period of the COVID-19 pandemic. As in previous research of this kind conducted by Lindley, Skead and Montalto in 2020,[25] non-random purpose sampling was employed, whereby a sample of respondents were selected from a population based on specific characteristics — specifically, their status as a past or present UWA PhD or SJD student or supervisor. Email invitations to complete the surveys were sent via internal mailing lists for enrolled UWA Law School PhD or SJD students (at the time of survey completion) and those who completed within the five years prior; and to UWA Law School supervisors and those who had retired within the five years prior. One survey was specific to the experiences and perceptions of UWA Law School PhD and/or SJD supervisors, and the other survey was specific to the experiences and perceptions of UWA Law School PhD and/or SJD students. The overall aim of both surveys was to identify optimal supervision practices according to students and supervisors. The student survey comprised eight questions, with four questions containing multiple parts; whereas the staff survey comprised 11 questions, with eight questions containing multiple parts. Questions included multiple choice, free text, and ranking formats.

Descriptive analyses of the quantitative data were conducted in R. Inductive thematic analyses of the free text survey data involved systematically scanning, coding, and thematically grouping responses. As with previous survey research of PhD program participants by Lindley, Skead and Montalto in 2020, there were several limitations of the present research.[26] Firstly, the student and supervisor sample sizes were small. This is predominantly a reflection of the small population of Law School PhD or SJD students and supervisors at the university. The study also relied on respondents self-selecting to complete the relevant survey. This may have skewed the results to reflect the experiences and perceptions of respondents who had shared factors underpinning their reasons to self-select participation in the survey, for example, the student may have experienced particularly positive or negative student-supervisor interactions. While this latter limitation cannot be entirely discounted, the nature of the initial background questions did allow some assessment of the diversity of respondents within each sample according to experience. Moreover, given the exploratory nature of the survey (and the recognised lack of inferential capabilities) we contend that the data still contributes valuable insights to the current knowledge on the topic, and provides a platform for future research.

III RESULTS

A total of 26 respondents completed the surveys; 15 respondents completed the supervisor survey, and 11 respondents completed the student survey. To provide context, the median duration to complete the supervisor survey was 16 minutes, and the median duration to complete the student survey was 11 minutes.

Experience

It was first important to initially establish the diversity of the supervisor and student samples with respect to the background of supervisor-related and student-related academic experience. The background experience characteristics of supervisor respondents are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Background personal experience characteristics of PhD or SJD supervisor respondents

|

|

Number of respondents

|

Proportion of respondents (%)

|

|

Qualification

|

|

|

|

PhD

|

10

|

67

|

|

SJD

|

1

|

7

|

|

Neither

|

4

|

27

|

|

Academic work experience

|

|

|

|

Less than 1 year

|

0

|

0

|

|

Between 1 and 5 years

|

0

|

0

|

|

Between 5 and 10 years

|

1

|

7

|

|

Between 10 and 20 years

|

6

|

40

|

|

More than 20 years

|

8

|

53

|

|

Supervisory experience (to completion)

|

|

|

|

PhD – principal supervisor

|

10

|

67

|

|

PhD – co-supervisor

|

12

|

80

|

|

SJD – principal

|

3

|

20

|

|

SJD – co-supervisor

|

0

|

0

|

|

Ever discontinued PhD or SJD supervision

|

|

|

|

Yes

|

9

|

60

|

|

No

|

6

|

40

|

Note: qualification and academic work experience proportions are rounded and therefore may not sum to 100; supervisory experience proportions may not sum to 100 due to respondents having the option to choose multiple responses.

The 11 supervisor respondents who had completed PhD or SJD studies all indicated that they believe this qualification helped them as a supervisor, for reasons such as understanding the experience of students, understanding the requirements of the qualification, and learning supervisory techniques or tools from their own experience of interacting with their PhD or SJD supervisor. Conversely, all four of the respondents who did not have a PhD or SJD indicated that they do not believe this limited them as a supervisor, for reasons such as research output equivalence through other qualifications or work experiences, and prior successful experiences in a supervisory capacity.

As reflected in Table 1, the academic work experience of our sample of supervisor respondents was skewed towards respondents who have had a longer academic career, compared to a junior academics, and having been a principal or co-supervisor of PhD candidates rather than SJD candidates. However, there was a more pronounced variation amongst the supervisor respondents in terms of the number of candidates they had supervised. For example, four respondents had supervised only one candidate as a principal supervisor, one respondent had supervised two PhD candidates, one had supervised three PhD candidates, one had supervised four PhD candidates, while three had supervised five or more PhD candidates, in this capacity.

Of the nine respondents who indicated that they had discontinued a PhD or SJD supervision, five indicated in a free-text follow-up that they had discontinued supervisions at the student’s request, and five indicated that they had discontinued supervisions themselves, this result included students that did not proceed beyond milestones such as confirmation of candidature. Student-related reasons for discontinuing supervisions according to the supervisor respondents included personal, family, and/or health-related issues of the student, a student changing their supervisory team to be more local to their living situation, and the student’s work commitments impacting their ability to complete a PhD. Supervisor-related reasons for discontinuing supervisions included changing institutions, a breach of trust by a student, and students failing to fulfil the requirements of a PhD to proceed past the initial milestones.

The background experience characteristics of student respondents are presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Background personal experience characteristics of PhD or SJD student respondents

|

|

Number of respondents

|

Proportion of respondents (%)

|

|

Enrolment status - temporal

|

|

|

|

Current PhD or SJD student

|

5

|

45

|

|

Previous PhD or SJD student

|

6

|

55

|

|

Enrolment status - workload

|

|

|

|

Enrolled full-time

|

8

|

73

|

|

Enrolled part-time

|

3

|

27

|

|

Progression status

|

|

|

|

Completed in the past 5 years

|

5

|

45

|

|

Less than 1 year

|

1

|

9

|

|

Between 1 and 2 years

|

1

|

9

|

|

Between 2 and 3 years

|

1

|

9

|

|

Between 3 and 4 years

|

1

|

9

|

|

Between 4 and 5 years

|

1

|

9

|

|

5 or more years

|

1

|

9

|

|

Whether on track to complete on time

|

|

|

|

Yes

|

10

|

91

|

|

No

|

1

|

9

|

|

Capacity worked with supervisor previously

|

|

|

|

Research assistant

|

3

|

27

|

|

Colleague

|

3

|

27

|

|

Masters

|

2

|

18

|

|

Honours

|

1

|

9

|

|

None

|

2

|

18

|

Note: proportions for the first four characteristics are rounded and therefore may not sum to 100; capacity worked with supervisor previously proportions may not sum to 100 due to respondents having the option to choose multiple responses. Additionally, one respondent did not provide details in relation to the capacity worked with supervisor previously characteristic.

Some characteristics of the student respondents were relatively evenly distributed among respondents (such as, current or previous enrolment status, and having worked with the supervisor previously), while other characteristics were skewed more in one direction (for example, most of the student respondents were enrolled full-time, and most of the student respondents believed they were on track to complete their qualification on time).

Supervisor Training

To understand the factors contributing to optimal supervision, it was also important to establish the perceptions and experiences of supervisors with respect to supervisor training. Table 3 presents a breakdown of supervisor respondents’ supervisor training experiences.

Table 3. Perceptions and experiences of supervisor respondents with respect to supervisor training

|

|

Number of respondents

|

Proportion of respondents (%)

|

|

Time since completing minimum induction training for supervisors (within

the past...)

|

|

|

|

12 months

|

6

|

40

|

|

3 years

|

5

|

33

|

|

5 years

|

2

|

13

|

|

Can’t recall

|

2

|

13

|

|

Whether feel adequate training and support is provided to

supervisors

|

|

|

|

Yes

|

14

|

93

|

|

No

|

1

|

7

|

|

Whether think further mandatory minimum training is necessary for all

supervisors

|

|

|

|

Yes

|

10

|

67

|

|

No

|

5

|

33

|

|

Whether think further mandatory minimum training is necessary for all

level 1 supervisors

|

|

|

|

Yes

|

11

|

73

|

|

No

|

4

|

27

|

|

Whether think further mandatory minimum training is necessary for all

level 2 supervisors

|

|

|

|

Yes

|

9

|

60

|

|

No

|

6

|

40

|

|

Whether think further mandatory minimum training is necessary for all

level 3 supervisors

|

|

|

|

Yes

|

9

|

60

|

|

No

|

6

|

40

|

Note: proportions are rounded and therefore may not sum to 100.

One area of training and support supervisor respondents felt would be beneficial to PhD or SJD supervisors was training relating to issues that arise in the process of supervision including conflict resolution strategies, for example:

‘[D]ealing with all the tangential and technical issues that arise in the course of a candidature such as student behaviour and misbehaviour, student depressions, student accidents, illness, life problems such as family illness.’

‘Training in conflict resolution should be available to all supervisors.’

‘It would also be helpful to reflect on how to manage different issues that arise in the process of PhD supervision. Perhaps this is more about sharing experiences than formal training.’

While this is generally available, another area of training and support supervisor respondents identified as potentially useful was a comprehensive training across all aspects of supervision for new supervisors, for example:

‘Definitely for early career supervisors, there needs to be comprehensive, mandatory training across all aspects of supervision (e.g. choosing a student; dealing with student issues [both the students having issues and problem students]; how to define &develop the supervisor-student relationship; supervisor expectations; dealing with different types of students [e.g. those who are more independent vs those who need more guidance]).’

‘All supervisors should receive training on how to supervise a project to completion including the different ways in which we can support students along the way - ie the stages of a PhD - commencing, drafting research proposals, establishing the structure and research design, drafting chapters, completion etc—and how supervision must change to accommodate these stages. This is not as easy as it seems and indeed may differ with various projects and students with some requiring quite nuanced supervision at the various stages and others less so.’

Other potentially useful areas of training and support that the supervisor respondents identified were ongoing training relating to the changing format of law theses, training on the specific institutional policies, training on how to support the professional development of students, training on the completion process for students nearing the end of their qualification, and training on how PhD supervision interacts with other structures at the university.

Optimal Supervision

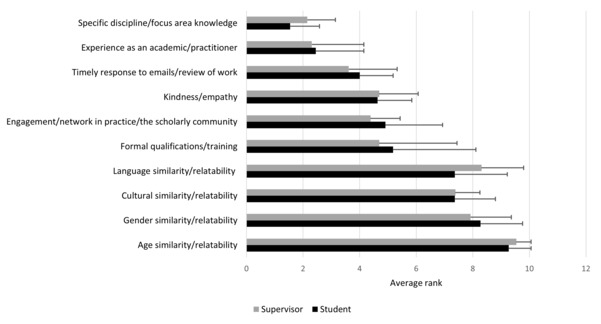

Given the areas of training and support identified as potentially useful by supervisor respondents, it is important to examine the factors that supervisors and students perceive as contributing to optimal supervision. Figure 1 shows supervisor respondent average rankings of supervisory characteristics by the importance they perceive HDR students attach to them compared to actual student respondent average rankings.

Figure 1. Supervisor respondent average rankings of supervisory characteristics by the importance they perceive PhD or SJD students attach to them compared to student respondent average rankings of supervisory characteristics by importance at the start of their program

Note: A rank of 1 indicates most important and a rank of 10 indicates least important. As such, the smaller the average rank value, the more important respondents perceive the supervisory characteristic is to students/themselves. Error bars represent standard deviation. Two supervisor respondents were excluded from analysis due to subsequent comments that indicated they felt the rankings did not represent their views. The sample sizes differ for the student (n = 11) and supervisor (n = 13) respondent samples.

As depicted in Figure 1, supervisors estimated the relative importance of different supervisory characteristics to students with a reasonable degree of accuracy. Although, there were two minor exceptions to this. Firstly, students placed ‘kindness/empathy’ as slightly more important than ‘engagement/network in practice/the scholarly community’, whereas supervisors estimated the latter as slightly more important than the former, when considering average ranks. Secondly, students placed ‘language similarity/relatability’ as more important than ‘cultural similarity/relatability’ and ‘gender similarity/relatability’, while supervisors estimated the two latter characteristics as more important than the former, when considering average ranks. Interestingly, ‘formal qualifications/training’ had the largest standard deviation in ranking for both the student and supervisor samples, indicating that the biggest difference in rankings was for this supervisory characteristic. There was a greater range of rankings provided for this characteristic: some students/supervisors perceived ‘formal qualifications/training’ as considerably more important to students than others, while the range of rankings for other supervisory characteristics was more uniform.

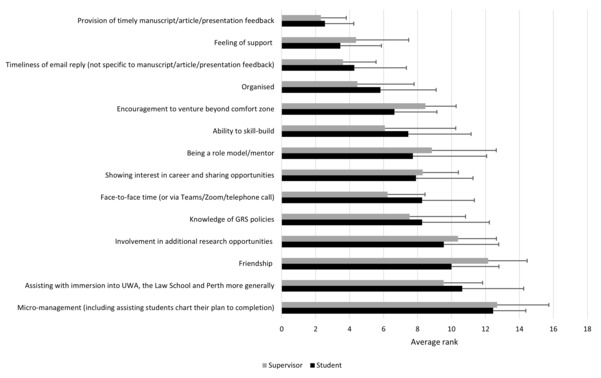

Despite general similarities among student and supervisor respondents in the average ranking of specific qualities perceived to contribute to optimal supervision, there was considerably more variety in average rank between the two samples across all qualities. Figure 2 shows a comparison of supervisor and student respondent average rankings of qualities perceived to contribute to optimal supervision by importance.

Figure 2. Comparison of supervisor and student respondent average rankings of qualities perceived to contribute to optimal supervision by importance

Note: A rank of 1 indicates most important and a rank of 14 indicates least important. As such, the smaller the average rank value, the more important respondents perceive the supervisory characteristic is. Error bars represent standard deviation. Two supervisor respondents were excluded from analysis due to subsequent comments that indicated they felt the rankings did not represent their views. The sample sizes differ for the student (n = 11) and supervisor (n = 13) respondent samples.

Particularly notable differences in the relative importance of qualities in contributing to optimal supervision among student and supervisor respondents were ‘encouragement to venture beyond comfort zone’, ‘face-to-face time (or via Teams/Zoom/telephone call)’, and ‘friendship’. Specifically, on average, students ranked ‘encouragement to venture beyond comfort zone’ and ‘friendship’ as more important for optimal supervision than supervisors. Conversely, on average, supervisors ranked ‘face-to-face time (or via Teams/Zoom/ telephone call)’ as more important for optimal supervision than students. Nevertheless, there were some important similarities in the qualities students and supervisors felt were most important for optimal supervision. Specifically, on average, both students and supervisors ranked ‘provision of timely manuscript/article/presentation feedback’, ‘feeling of support’, ‘timeliness of email reply (not specific to manuscript/ article/ presentation feedback)’, and ‘organised’ as the four most important qualities for optimal supervision.

It should also be noted that two supervisor respondents were excluded from this analysis due to subsequent comments indicating that they felt the ranking format/options misrepresented their views on optimal supervision. It is important to represent those views here, though the Figures and Tables and survey quotes, as they may have a bearing on the design and focus of future research into optimal supervision. Both respondents made comments that they would rank many (or all) qualities as equally important, while one of these respondents also stated that they perceived some of the options as logistical issues that could be solved rather than ‘qualities’ contributing to optimal supervision and that other options were subjective in meaning.

Given the exploratory nature of the research, it was also important to identify other qualities beyond those presented in the survey that students and supervisors felt were important for optimal supervision. Supervisor respondents identified encouraging passion in their students for research, having an interest in a student’s research topic, encouraging critical thinking in research, normalising the PhD experience by explaining common challenges, establishing and reviewing expectations of the student and supervisor, and adapting supervisory needs to the individual at various stages of the HDR journey, as supervisory qualities important for optimal supervision. Students also identified qualities relating to inspiring a passion for the research, and having an interest in a student’s research topic, for example:

‘Genuine interest in PhD topic and taking the time to discuss it. I think many of us have missed a “sparring partner”. I chose to venture beyond the interest of my principal supervisor, so I understand a lack of interest there, but, generally, I've felt like my supervisor never really had the time for an in-depth discussion due to competing demands.’

‘Appreciation of the shared nature, the dialogue, of feedback.’

Other qualities identified by students as important for optimal supervision were providing direct, honest feedback, and suggesting alternative research pathways where appropriate.

Another way in which qualities or characteristics of optimal supervision were elicited from students and supervisors was by asking the best advice they had given students (supervisors), and the best advice they had received (students). Four student respondents mentioned technical advice including changing their thesis title, writing more concisely, writing the thesis introduction early on to frame and limit the topic, and suggesting a good document management system with drafts organised by date. Two student respondents made comments relating to advice on time management, including trying not to work during the holidays and to not over-prepare for tasks to allow time for other important tasks. Finally, four student respondents made comments about other more general advice received, including learning to live with imperfection, encouraging deep reflection on alternative points of view when assumptions were made in their own writing, encouraging participation in conferences, not give up, and to stay humble. Furthermore, in a follow-up question, one student respondent indicated that they may have removed a supervisor that did not contribute sufficiently to the supervisory team, and another student respondent indicated that they would include a supervisor in their supervisory team who had knowledge of the methodology applied in the PhD.

Some of the best advice given by supervisor respondents aligned with that received by student respondents, such as advising students to write early and consistently, for example:

‘I get my students to write consistently and to submit that writing for ongoing feedback. ie Stick to a regular writing and submission timetable.’

‘Start drafting parts of your research (even small parts) as early as you can, because this process reveals what you don't understand or don't really know.’

Other advice that aligned with student respondent comments was advising students to avoid trying to achieve perfection in their work, and the related concept of keeping focussed on the task requirements, for example:

‘Don't let the right be the enemy of the good. It doesn't have to be perfect - it needs to make a meaningful contribution to the body of work in their thesis field.’

‘There is research to be done after the PhD/SJD is completed. You don't have to solve everything in the PhD/SJD.’

Other ‘best advice’ given by supervisors was not mentioned by the student respondents, such as advising students to be clear about their motivation for doing the PhD, for example:

‘All students need to be sure, as they start their PhD, that they are doing so for the right reasons and have chosen a topic that aligns with their personal and professional interests. They will need passion in their chosen topic/area to carry them through their research journey.’

As well as more specific law discipline-focussed advice for students to keep up to date with current news events to contextualise their research, offered by one supervisor respondent:

‘Read the newspaper every day. You'll pick up all the legal literature in the course of your research activities but it is only of value if you place your work in the context of real world events and pressures.’

The number of student respondents who indicated that they would supervise future HDR students the way they had been supervised (n = 6) was similar to the number who indicated they would not supervise future students in the same way (n = 5).

Disputes

In order to identify aspects of supervisor-student relationships that significantly depart from optimal supervision practices, it was important to gauge student and supervisor perceptions and experiences of formal and informal disputes.[27] Most of the student respondents indicated that they were aware they could make complaints about supervision (82%; n = 9). Despite this, no student respondents had made a formal complaint. However, four of the 11 student respondents indicated that they had made an informal complaint. The informal complaints included the lack of availability of a supervisor, unfair assertions made by a supervisor, a lack of understanding about personal circumstances, exploitation of the supervisor/supervisee power imbalance, harsh treatment, belittling verbal communication, and ‘borderline bullying’. Three of the students who made an informal complaint indicated that the outcome of the complaints process resolved the situation between them and their supervisor to enable a continued relationship. The remaining student who made an informal complaint, who cited exploitation of power imbalance, harsh treatment, and ‘borderline bullying’ as the grounds of their complaint, indicated that the outcome of the complaints process did not resolve the situation between them and their supervisor. Of the seven student respondents to indicate that they had not made any formal or informal complaints, two indicated that they had experienced difficulties with supervision. The nature of these difficulties included a lack of substantive feedback on drafts from their secondary supervisor and having a supervisor who they regarded as sexist and inexperienced.

Two of the 15 supervisor respondents indicated that they had been involved in a formal complaint. The persons making these two complaints were a student and a third party, respectively. The complaints related to the nature of communication to a student that their candidature was not confirmed, and unfairness of process leading to the decision to reject a PhD thesis. In the first case, it was identified that the outcome of the complaints process did not resolve the situation, which precluded ongoing supervision. Conversely, the outcome of the complaints process for the second complaint did resolve the situation. Six of the 15 staff respondents indicated that they had been involved in an informal complaint. The persons identified as making the complaints were students (n = 3), and the supervisors themselves (n = 3). Student complaints related to the timeliness and nature of communication/feedback as well as the conduct of a co-supervisor, and the nature of communication to a student who was not recommended for confirmation of candidature and advised to withdraw. The third complaint was identified as being obscure, with no specific details provided. Supervisor complaints related to bullying and aggression by a student; breach of trust by a student; and complaints by students include, poor advice to, and support of, a student in helping them to achieve their goal of becoming an academic. Three of the informal complaints were identified as having been resolved as an outcome of the complaints process, while the remaining three were not resolved—precluding ongoing supervision. Of the seven supervisor respondents to indicate that they had not been involved in either a formal or informal complaint, four identified that they had experienced difficulties with a supervision. These difficulties included crippling perfectionism and related mental health issues of students; students disengaging from the project or not making progress due to other commitments or doubt about whether they wanted to do a PhD; and students lacking sufficient research and writing skills at the time they commenced the project despite meeting the admission criteria.

When asked if they had any recommendations for improving the current Graduate Research School (GRS)/Law School dispute resolution system, five supervisor respondents indicated that they had not had any experience with the dispute resolution system; two indicated that they did not have a detailed understanding of the dispute resolution system but had past experiences where it worked satisfactorily; and one stated that outcomes appeared to be dependent on who the GRS representative was, citing their experience of bullying and aggression by a student which was dismissed by one GRS representative but dealt with very effectively by the next GRS representative.

IV DISCUSSION

The PhD experience has been compared to Rapunzel isolated in the tower working diligently with the wicked witch supervisor providing necessary sustenance but not much else.[28] However, HDR students are more likely to complete and have a higher rate of satisfaction with the process when they have a strong positive relationship with their supervisor.[29] The HDR process has both intellectual and emotional challenges,[30] which means the supervisory role is multi-faceted requiring academic and interpersonal skills,[31] which may need CPD to ensure best practice teaching pedagogy for this specialised role.

Experience and Supervisor Training

All supervising academics must complete an induction course offered by the GRS. While a majority of supervisor respondents considered that the professional development (training) and support provided by the institution were adequate, results indicated a perception that with greater academic experience attained that there is a lesser need for ongoing training. Twenty six percent of supervisor respondents had not engaged in training for over five years, and 60% for over three years. In relation to the need for ongoing training, 33% felt that supervisor training was not necessary for all supervisors. Responses indicated that the need for less training was predicated on the level of academic experience, 73% responding that further mandatory minimum training was necessary for level one supervisors compared to 60 percent responding it was necessary for level two (L2) and three supervisors (L3). Currently, UWA requires L2 and L3 supervisors to read the Supervisor Refresher Module or engage in some other form of professional development at least once every four years.[32] The refresher module mandates CPD for all supervisors aligned with the 2021 Australian Council of Graduate Research supervision guidelines.[33] These results raise two questions. First, are supervisors perceiving academic acumen and experience as correlating with best practice teaching skills, and secondly, is the institution providing professional development by updating the training and/or providing additional skills training in subjects necessary to maintain or attain best practice supervision as teaching methodology evolves? In a nutshell, is the response reflective of the perception that a highly skilled academic does not need teaching methodology CPD for their role as a supervisor, or that the CPD available does not provide suitable upskilling in teaching practice?

Tertiary teaching is unique in that tertiary teachers do not need and generally do not have formal teaching qualifications. Currently, a pre-tertiary teaching qualification requires a four year undergraduate Bachelor of Education, specialising in primary, secondary or early childhood studies, or an equivalent two year Masters of Education.[34] In disciplines such as teaching, law, psychology, physical and medical professions, new methods of best practice are continually evolving, and a practitioner is required to undertake CPD to ensure they are employing the best practice methods for their discipline.[35] So, after qualifying, a Western Australian-based teacher is required to fulfil 20 hours of CPD per annum, and may specialise by completing post-graduate qualifications in areas such as special needs or learning difficulties.[36] Because tertiary teachers are not necessarily trained in higher education, there is potentially a greater need for mandatory teaching skills training and CPD, particularly if the academic intends to specialise in a teaching area such as HDR supervision.

On the other hand, the supervisors’ response to the survey may indicate that the institution is not offering adequate CPD opportunities. For example, the supervisor training may be static, geared towards science-based disciplines, and not address developing personal aspects, or dealing with difficulties or disputes. Supervisors expressed a need for training in conflict resolution, dealing with student declining mental health and relationship development. The UWA GRS supervisor refresher course is largely a recap of the supervisor induction course, updating policy and services. In 2021, the GRS provide optional online and in-person workshops establishing a GRS Supervision Professional Development Program.[37] The eight online modules are designed to equip PhD supervisors specifically to support their students’ development into independent researchers through comprehensive training in core principles and practices of Doctoral supervision.[38] Optional CPD offered by the GRS prior to 2022 included topics such as ‘Finding the Right Student’, ‘Expectations, Relationships and Wellbeing’, ‘Research Students and Mental Health’ as well more mainstream topics to develop research, writing and teamwork skills.[39] One means of providing a greater range of CPD opportunities may be by facilitating cross institution access to supervisor training modules. For example, Monash University offers CPD modules and tools, such as a diagnostic tool to target specific aspects of professional development, and topics such as ‘Developing the Researcher and Enabling Progress’, ‘Effective Feedback’, ‘Supporting your Candidate’, and ‘Developing your Supervisory Practice’, which are CPDs not currently available from the UWA GRS.[40] Supervisor CPD needs to be targeted, it necessarily needs to include administrative practice but also needs to be extended to provide exploration of the emotional demands of supervision and ‘to reflexively and investigate and contemplate their supervision practices’.[41]

The University of Otago in New Zealand recognises that a good supervisory relationship is the key to a successful supervision, a successful supervision is both the desired end result (the award) and the process achieving that result.[42] In regard to the process, ‘the key word is relationship’.[43] The relationship should be professional open and honest and based on mutual respect and trust.[44] In 2022, the University of Otago provided 54 CPD workshops specifically designed to support HDR supervisors and enhance supervision methodology and practice because research unequivocally indicates good supervisory practices are an essential factor that effects both the success and the quality of the research experience.[45] The Otago program offers a comprehensive range of in-person or online pedagogical workshops throughout the year to develop supervisor skills targeting key aspects and processes, such as ‘Pastoral Care of Candidates; What doctoral supervisors need to know’, ‘Mental Health, Well-being and Productivity’, ‘Supporting your Supervisee’, ‘Pedagogical Approaches and Supervisory Styles’, and ‘Providing Feedback in Postgraduate Supervision’.[46]

The complex and demanding role of a supervisor means that CPD (via workshops and review of literature) is necessary to optimise and improve outcomes.[47] However, uptake of workshops for developing teaching or supervisory skills and methodology maybe low even when provided; survey results indicated 27% of supervisors had not participated in training in five years or more and 60% in three or more years. Introduction of a mandatory CPD point system in conjunction with access to programs similar to the University of Otago may ensure that supervisors of all levels are acquiring or maintaining best practice teaching skills.

Optimising Supervision: Personal and Practical Aspects Ranking

Students ranked characteristics of a personal nature – such as support, empathy, and encouragement to venture beyond their comfort zone – as being of higher importance than characteristics of a practical nature — for example, career development and networking opportunities — which were more highly valorised by supervisors. ‘Feeling of support’ was ranked by students as the second most important aspect of the relationship after timely feedback. Students ranked face to face time lower than supervisors, potentially indicating that the quality, rather than the quantity of the contact time is the most important form of support. Both students and supervisors ranked timely feedback as the most important relationship characteristic. However, we did not offer a sliding scale of how ‘timely’ is defined, nor did we delve into appropriate timeliness for various tasks. For example, expectations of timeliness would differ for email replies compared to critical feedback on one or more chapters. Oral or written feedback will typically be the main form of communication between the students and their supervisors, and thus feedback should inherently incorporate the personal aspects identified by students such as feeling supported, empathy, and encouragement. For example, PhD students, who have generally been successful in their prior academic pursuits, may be unprepared for the first revisions and criticisms — however well-intentioned — which may lead to students feeling ‘isolated and alone in the uncertainty’.[48] Supervisors can improve communication and minimise feelings of isolation by going beyond feedback that critically analyses by providing supportive feedback that normalises this experience and offers encouragement.[49]

Supervisors play a vital role in providing support to students. Research demonstrates that students are motivated when their early efforts are encouraged and criticism is initially withheld at the beginning of their PhD journey.[50] Students are motivated by supportive, timely, meaningful, and encouraging feedback that shows their supervisor believes in them.[51] Indeed, feedback is an ‘intrinsically emotional business’[52] that may seek to support the student’s academic writing development. One student survey respondent noted that one supervisor’s feedback on drafts focussing on grammar and sentence structure details left them feeling negative and that the supervisor was not seeing the ‘bigger picture’.[53] In contrast, targeted critical feedback that was supportive and coupled with reassurance about the quality of the student’s work provided the necessary motivational balance that allowed for thesis completion.[54] Other research indicates supervisors requiring ‘polished’ academic writing rather than encouraging thesis completion can lead to attrition, and that further ‘polishing’ did not contribute to better employment opportunities.[55] The converse may also apply — supervisors may require students to overcome their inherent perfectionism, as one supervisor survey respondent noted, ‘It doesn't have to be perfect’.

There is a large body of literature considering effective feedback and how to develop best practice feedback, the impact of poor teacher feedback skills on student confidence and learning, and the role of emotion in learning.[56] Currently, there are limited resources available through the UWA GRS on the provision of effective feedback.[57] Students can receive feedback on written work from an academic (other than their supervisors) through the ‘Studiosity’[58] service, however while a useful resource, it does not address feedback skills development within the supervisory relationship.[59] Given the importance of feedback to the supervisory relationship, institutions may consider providing links to further resources on this topic,[60] for example, as part of mandatory supervisor refresher courses.

Personal tools for coping with critical feedback can also be developed for, and by students. One institution has introduced student support programs for first year PhD students.[61] The focus of the program is how to survive and complete a PhD program, choose a supervisor, and cultivate a constructive relationship.[62] A main topic is getting and giving feedback, and understanding what good feedback looks like.[63] Students have described program as a ‘weekly therapy session’ that often revolves around the stress of being critiqued.[64] For many, the initial shock of seeing a first draft review may send them into panic mode.[65] However, students comment that professional academics normalising the process, often with examples of their own earlier work, has assisted them to accept the necessity of the critical process, and rise to the challenge.[66] Students respond well, even to harsh criticism, when they know the supervisor is acting in their best interests and the process of critique is mixed with sympathy and understanding.[67] This observation further reflects the need to develop a robust supportive supervisory relationship in which the student can accept and constructively incorporate critical feedback.

Dispute Resolution

The supervisory relationship is subject to a power imbalance,[68] so students are more likely to be reticent about resolving issues early on and may decide to put up with the problem rather than potentially jeopardise the supervision, consistent with our findings. Moak succinctly notes that ‘students feel subordinate to faculty because they are’.[69] More dominant personality types may escalate and exacerbate the issue by not using a safe-setting or having poor communication skills. The student survey responses indicated that while 82% of respondents were aware of the available GRS complaints procedure, zero students had made a formal complaint and 36% of respondents had made an informal compliant. Of the students who made an informal complaint, 75% of those were resolved and enabled the relationship to continue. Of the total student participants, 18% indicated that although they had experienced difficulties with the supervision, they opted not to make a complaint of any kind.

The results of the supervisor survey are indicative of the reticence of candidates to engage in the complaints process to resolve supervisory issues. Collectively, the UWA Law School supervisors who participated in the survey have been practicing academics for over 250 years, however, during that time, the supervisors had received only two formal complaints and six informal complaints. The resolution process for the informal complaints were split 50/50, that is 50% continued with the supervision and 50% suspended the supervision. The lack of formal complaints and the variable results of the informal complaints procedure raise the question of whether suitable dispute resolution processes are available, and/or whether supervisors have sufficient training to resolve conflicts. The supervisor survey respondents indicated that conflict resolution is an area where additional resources or CPD would be welcomed.

Supervisors need to recognise the power imbalance in the relationship and develop counselling and mediation skills.[70] A novel approach to developing the relationship may include engaging in social activities outside of academia.[71] This approach may go a long way in breaking down the power imbalance and could enable the parties to constructively discuss issues on a levelled platform, however, this method requires well developed mentoring skills.[72] Research indicates that respecting and listening to the supervisee are key aspects of supervisors’ role as a mentor.[73] This also brings into focus the usefulness of the role of an HDR mentor, as highlighted by Lindley, Skead and Montalto,[74] who may be a junior academic on faculty and fills the support gap somewhere between supervisor and peer. Supervisors will need to develop conflict resolution and mentoring skills through CPD or other training to achieve optimal supervision relationships.

V CONCLUSION

Drawing on perceptions yielded from two online surveys targeting UWA Law School current and recently completed HDR students, and current and recently retired HDR supervisors, this article provides insight into ways in which HDR supervision can be optimised. Survey results found both students and supervisors shared four qualities they considered most important for optimal supervision, namely timely feedback, support, timely replies, and organisation. As these qualities are subjective, establishing expectations early in the relationship is integral to develop an optimal supervisory relationship, which will contribute to the timely completion of the PhD thesis. Supportive and organised supervisors require skill-building and resources specifically designed to assist the relationship to develop positively over the duration of the project, which can be provided through CPD. While universities provide a range of skill-building for supervisors, there may be limitations as to the breadth of offerings, particularly those relevant to law. As such, we conclude that cross-institutional supervisor CPD programs — particularly relating to conflict resolution and interpersonal skills — will support law schools to share knowledge and skill-build their HDR supervisors to support the next generation of law academics.

* Jade Lindley is an Associate Professor at the UWA Law School, the University of Western Australia. Natalie Brown is a Lecturer at the UWA Law School, the University of Western Australia. Liam Quinn is a PhD graduate from the UWA Law School, the University of Western Australia.

1 Jade Lindley, Natalie Skead and Michael Montalto, ‘Enhancing Institutional Support to Ensure Timely PhD Completions in Law’ (2020) 30(1) Legal Education Review 1.

[2] Ibid 28.

[3] J Stubb, K Pyhalto and K Lonka, ‘Balancing Between Inspiration And Exhaustion: PhD Students’ Experiences Socio-Psychological Well-Being’ (2011) 33(1) Studies in Continuing Education 33, 45–6.

[4] Ibid 46–8.

[5] Lorna Moxham, Trudy Dwyer and Kerry Reid-Searle, ‘Articulating Expectations For PhD Candidature Upon Commencement: Ensuring Supervisor/Student “Best Fit”’ (2013) 35(4) Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management 345, 345, 347; Kim Beasy, Sherridan Emery and Joseph Crawford, ‘Drowning in the Shallows: An Australian Study of the PhD Experience of Wellbeing’ (2021) 26(4) Teaching in Higher Education 602; KM Barry et al, ‘Psychological Health of Doctoral Candidates, Study-Related Challenges and Perceived Performance’ (2018) 37(3) Higher Education Research and Development 468; Susan Guthrie et al, ‘Understanding Mental Health in the Research Environment: A Rapid Evidence Assessment’ (2018) 7(3) Rand Health Quarterly 2.

[6] Moxham, Dwyer and Reid-Searle (n 5) 352.

[7] Stacey C Moak and Jeffery T Walker, ‘How To Be A Successful Mentor’ (2014) 30(4) Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice 427, 438.

[8] Australian Council of Graduate Research, Mental Health and Wellbeing in Graduate Research Education (Version 2: August 2021) [8]–[9].

[9] Stubb, Pyhalto and Lonka (n 3) 34, 35, 44. See also, Ben Marder et al, ‘Impression Formation Of Phd Supervisors During Student-Led Selection: An Examination Of UK Business Schools With A Focus On Staff Profiles’, (2021) 19 The International Journal of Management Education 1, 3.

[10] Stubb, Pyhalto and Lonka (n 3) 39.

[11] Ibid 39–40.

[12] Ibid 47.

[13] Marder et al (n 9) 2, 6–10.

[14] Terry Hutchinson and Nigel Duncan, ‘Describing and Defining What We Do: Doctrinal Legal Research’ [2012] DeakinLawRw 4; (2012) 17(1) Deakin Law Review 83, 99.

[15] Lindley, Skead and Montalto (n 1) 7. For comment on completion rates specific to law see Hutchinson and Duncan (n 14) 97. See also, completion times for humanities in comparison to sciences, Ronald Ehrenberg et al, ‘Inside the Black Box of Doctoral Education: What Program Characteristics Influence Doctoral Students Attrition and Graduation Probabilities?’ (2007) 29(2) Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis 134, 134–5.

[16] Ehrenberg et al (n 15) 135, 147.

[17] See Stubb, Pyhalto and Lonka (n 3) 38, Table 1, which indicates that 93% of humanities PhD students worked alone in comparison to 43% in medicine and 78% in behavioural sciences.

[18] For a comparison of well-defined disciplines such as mathematics and chemistry (hard sciences) where the level of agreement between academics is higher than ill-defined disciplines in which academics have several or sometimes opposing views on acceptable ways of approaching a research topic, see Stubb, Pyhalto and Lonka (n 3) 35.

[19] For example, students’ perception that others do not struggle in the program, described as ‘academic imposter syndrome’ — see Moak and Walker (n 7) 430–1.

[20] Marder et al (n 9) 2, 6–10.

[21] Ibid 3–4.

[22] Ibid 2; Moak and Walker (n 7) 438.

[23] Moxham, Dwyer and Reid-Searle (n 5) 346; Moak and Walker (n 7) 428.

[24] Moak and Walker (n 7) 436, 438.

[25] Lindley, Skead and Montalto (n 1).

[26] Ibid.

[27] Informal complaints may be via the Dean/Head of School, as compared to formal complaints which are through the Graduate Research School.

[28] Melissa De Zwart and Bernadette Richards, ‘Wi-Fi in the Ivory Tower: Reducing Isolation of the Law PhD Student Through Social Media Networks’ (2014) 14 (1) Queensland University of Technology Law Review Special Edition: Wellness for Law 81, 81.

[29] Moak and Walker (n 7) 430.

[30] Stubb, Pyhalto and Lonka (n 3) 33.

[31] Moak and Walker (n 7) 430; Marder et al (n 9) 3.

[32] University of Western Australia Graduate Research School (‘UWA GRS’), Supervisor Workshops <https://www.postgraduate.uwa.edu.au/staff/supervisors/workshops#online>.

[33] Ibid; Australian Council of Graduate Research, Good Practice Guidelines (Guidelines, version 2, August 2021) <https://www.acgr.edu.au/good-practice/best-practice/>.

[34] Government of Western Australia Teachers Registration Board, Accredited Initial Teacher Education Programs in Western Australia <https://www.trb.wa.gov.au/Initial-Teacher-Education-Programs/Accredited-initial-teacher-education-programs>.

[35] Teachers Registration Act 2012 (WA) s 22(2)(c); Teacher Registration (General) Regulations 2012 (WA) r 13; Government of Western Australia Teachers Registration Board, Professional Learning <https://www.trb.wa.gov.au/Teacher-Registration/Currently-registered-teachers/Renewal-of-registration/Professional-learning>; Government of Western Australia Teachers Registration Board, Professional Standards for Teachers in Western Australia <https://www.trb.wa.gov.au/DesktopModules/mvc/TrbDownload/PublishedDoc.aspx?number=D19/065548>.

[36] 20 hours CPD is the common requirement for teachers in other Australian States. For example, see Victorian Institute of Teaching, Professional Practice and Learning Requirements <https://www.vit.vic.edu.au/maintain/requirements>; Edufolios, Teacher Professional Development Requirements by State and Territory <https://edufolios.org/teacher-professional-learning-requirements-by-state-and-territory/>; Edith Cowan University (ECU), How can I become a Special Needs teacher?

<https://askus2.ecu.edu.au/s/article/000001392>.

[37] UWA GRS (n 32).

[38] Ibid.

[39] Ibid.

[40] Monash University Graduate Research School, Training and Development <https://www.monash.edu/graduate-research/supervision/training#tabs__2326750-02>.

[41] Moxham, Dwyer and Reid-Searle (n 5) 352.

[42] The University of Otago, Graduate Research School PhD Supervision <https://www.otago.ac.nz/graduate-research/current-students/otago703140.html>.

[43] Ibid.

[44] Ibid.

[45] The University of Otago, Higher Education Centre, The Otago Doctoral Supervision Program (2022)

<https://www.otago.ac.nz/hedc/otago831677.pdf>.

[46] Ibid. The examples selected relate to this article’s theme of the importance of relationship, however, the program also offers support on practical procedures, such as preparing for viva voce, and key administrative processes for supervisors.

[47] Stan Taylor, ‘Good Supervisory Practice Framework’, United Kingdom Council for Graduate Education, (June 2019) <https://supervision.ukcge.ac.uk/good-supervisory-practice-framework/> 2, 10.

[48] Moak and Walker (n 7) 430.

[49] Ibid 431.

[50] Sian Lindsay, ‘What Works For Doctoral Students In Completing Their Thesis’ (2015) 20(2) Teaching in Higher Education 183, 185.

[51] Ibid 191.

[52] Elizabeth Molloy, Francesc Borrell-Carrio, and Ron Epstein, ‘The Impact Of Emotions In Feedback’ in David Boud and Elizabeth Molloy (eds), Feedback in Higher and Professional Education: Understanding it and Doing It Well (Routledge, 2013) chapter 4, 63.

[54] Ibid.

[55] Ehrenberg et al (n 15) 147, 150.

[56] Molloy, Borrell-Carrio and Epstein (n 525252) 51–2; Clair Doloriert, Sally Sambrook and Jim Stewart, ‘Power and Emotion in Doctoral Supervision: Implications for HRD’ (2012) 36(7) European Journal of Training and Development 732; David Carless and David Boud, ‘The Development of Student Feedback Literacy: Enabling Uptake of Feedback’ (2018) 43(8) Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education 1315; Elke Stracke and Vijay Kumar, ‘Encouraging Dialogue in Doctoral Supervision: The Development of the Feedback Expectation Tool’ (2020) 15 International Journal of Doctoral Studies 265; Margot Pearson and Angela Brew, ‘Research Training and Supervision Development’ (2002) 27(2) Studies in Higher Education 135.

[57] UWA GRS (n 32). The GRS provides the following supervisor resource handbook: Commonwealth Government, Office of Learning and Teaching, ‘Supervision of Higher Degree by Research Students: Supervisor Resource Book’ (Supervisor Handbook). The Supervisor Handbook deals with feedback under heading [G] ‘Managing relationships with the student’ that notes frustrations can occur in the end stages of the project in relation to timely or critical feedback (110) and that a supervisor should give positive as well as negative feedback (128). The rest of the advice in this section is by way of ‘case-studies’ under various titles. For example, ‘Case of a student apparently impervious to feedback’ G1.4 (114) and ‘Case of a student continually crying in supervision meetings’ G1.5 (116), and ‘Case of a student breaking down’ G1.6 (116). The advice is not supported by references and does not offer support resources by way of links. In general, the case studies appear to focus on the student as having the issue and needing to be managed by the supervisor.

[58] See the University of Western Australia, Studiosity <https://www.uwa.edu.au/education/educational-enhancement-unit/Strategic-Projects/Studiosity>.

[59] UWA GRS, Supervisor Workshops, Supervision Professional Development Program (n 3257). See especially Unit 5, ‘HDR Student Support’ slide 17/26 <https://www.postgraduate.uwa.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0006/3445611/SvisorInductionModule_Unit5.pdf>.

[60] For example, literary sources such as Molloy, Borrell-Carrio and Epstein (n 5252525252). See also the collaborative research project between Monash University, Deakin University and the University of Melbourne led by David Boud and Michael Henderson, Feedback for Learning Closing the Assessment Loop <https://feedbackforlearning.org/>, which offers a comprehensive staff resource for feedback strategies as well as links to texts or articles and online resources including ‘Institute Learning Designer’ to organise group workshops for teaching peers on upskill feedback and use of learning technologies. See also Federation University, Feedback and Learning <https://federation.edu.au/staff/learning-and-teaching/teaching-practice/feedback/feedback-learning>, specifically the ‘Technologies to enhance feedback’ and the ‘Resources, strategies or assistance’ sections.

[61] Moak and Walker (n 7) 434–5.

[62] Ibid 434.

[63] Ibid.

[64] Ibid.

[65] Ibid.

[66] Ibid 435.

[67] Ibid.

[68] Ibid 436; Moxham, Dwyer and Reid-Searle (n 5) 352.

[69] Moak and Walker (n 7) 436.

[70] Catherine Manathunga, ‘Supervision as Mentoring: The Role of Power and Boundary Crossing’ (2007) 29(2) Studies in Continuing Education 207; Maija Vähämäki, Essi Saru and Lauri-Matti Palmunen, ‘Doctoral Supervision as an Academic Practice and Leader–Member Relationship: A Critical Approach to Relationship Dynamics’ (2021) 19(3) The International Journal of Management Education 100510; Melinda Kirk and Kylie Lipscombe, ‘When a Postgraduate Student Becomes a Novice Researcher and a Supervisor Becomes a Mentor: A Journey of Research Identity Development’ (2019) 15(2) Studying Teacher Education 179.

[71] Moak and Walker (n 7) 437–9.

[72] Ibid 440.

[73] Ibid 430–2.

[74] Lindley, Skead and Montalto (n 1).

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/WALawTRw/2024/5.html