|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

University of Technology Sydney Law Research Series |

Last Updated: 16 February 2017

Models of Judicial Tenure:

Reconsidering Life Limits, Age Limits and Term Limits for Judges

Brian Opeskin[*]

ABSTRACT

Tenure is an important facet of judicial independence and a key principle underpinning the rule of law, yet its protection varies markedly from country to country. This article examines the historical development and empirical experience of three pre-eminent appellate courts—the Supreme Court of the United States, the High Court of Australia and the Constitutional Court of South Africa—as examples of prevalent models of tenure, namely, life tenure, age limits and term limits. Dissatisfaction with tenure arrangements in each jurisdiction has been impelled by increasing human longevity, growing awareness of incapacities that accompany ageing, and changing attitudes to age discrimination. These developments have led to constitutional and legislative reforms to ameliorate the problems that inhere in different models of tenure. However, the choice between models, and between key parameters within each model, reflect complex policy preferences. The article concludes that hybrid arrangements that incorporate age limits and term limits provide an appropriate compromise between competing policy objectives.

KEYWORDS

age limits, judicial tenure, life tenure, mandatory retirement, senility, term limits

1. Introduction

Judicial tenure is an important facet of judicial independence and a key principle underpinning the rule of law. Robust provisions for tenure allow judges the freedom to decide cases according to law, without fearing reprisal through demotion or dismissal, or anticipating favour through promotion or re-appointment, by executive government. It has not always been so. In Seventeenth Century England, judges were commonly transferred or dismissed after deciding cases in a manner that displeased the monarch who appointed them. Since then, systems of government have evolved to give much greater protection to judicial officers by enshrining principles of tenure in law and practice, although the evolutionary process has been uneven and some countries have a chequered history of judicial independence.

Tenure is not a binary concept that either exists or not. Provisions relating to tenure can be crafted in diverse ways that support a greater or lesser degree of independence. This article examines three circumstances in which judicial office is terminated by the occurrence of a particular event. These events are: (a) death, (b) attaining a mandatory retirement age, and (c) reaching the end of a fixed term appointment, and they correspond to three models of tenure that are here called life limits, age limits and term limits. They are not the only circumstances in which judges cease to hold office. Judges may voluntarily resign by reason of ill health, infirmity, boredom or impecuniosity, or to pursue other positions; they may be nudged out of office by their peers or head of jurisdiction if their capacity to discharge the functions of office is in doubt;[1] or they may be removed by reason of misconduct or incapacity. The last process—removal—is so purposefully demanding that it is seldom invoked. Yet, despite its rarity, removal has attracted substantial academic commentary while the literature on life limits, age limits and term limits is meagre.

This article addresses the gap by examining constitutional models of judicial tenure that account for a large proportion of judicial terminations. It does so by investigating three courts that exemplify disparate practices—the Supreme Court of the United States in the case of life limits; the High Court of Australia in the case of age limits; and the Constitutional Court of South Africa in the case of term limits.[2] These courts, which will be abbreviated to ‘the Supreme Court, ‘the High Court’ and ‘the Constitutional Court’, are pre-eminent appellate courts and can loosely be described as apex courts.[3]

An examination of models of judicial tenure is timely because there appears to be dissatisfaction with historical models and growing divergence in contemporary constitutional practice. While the importance of judicial independence has not diminished, the social context in which independence is to be protected has altered, necessitating a reappraisal of available tenure options. The most conspicuous social changes have been the marked rise in human longevity, the corresponding exposure of incapacities associated with senescence, and changing attitudes towards age-based discrimination.

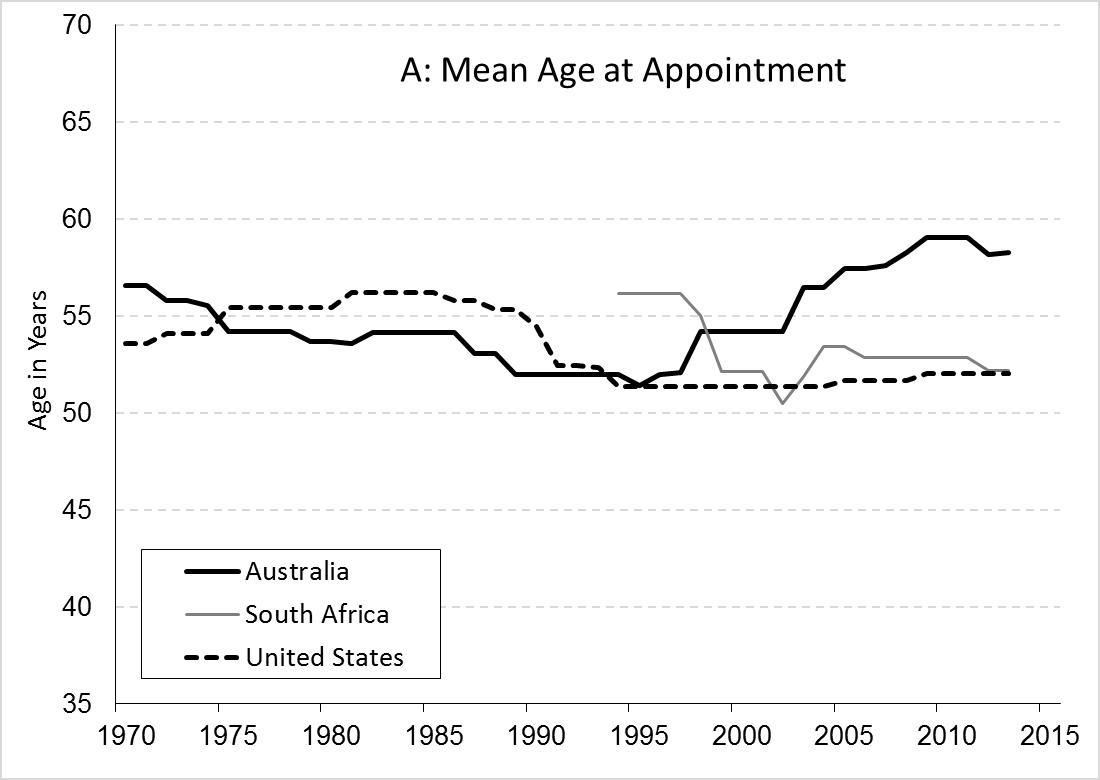

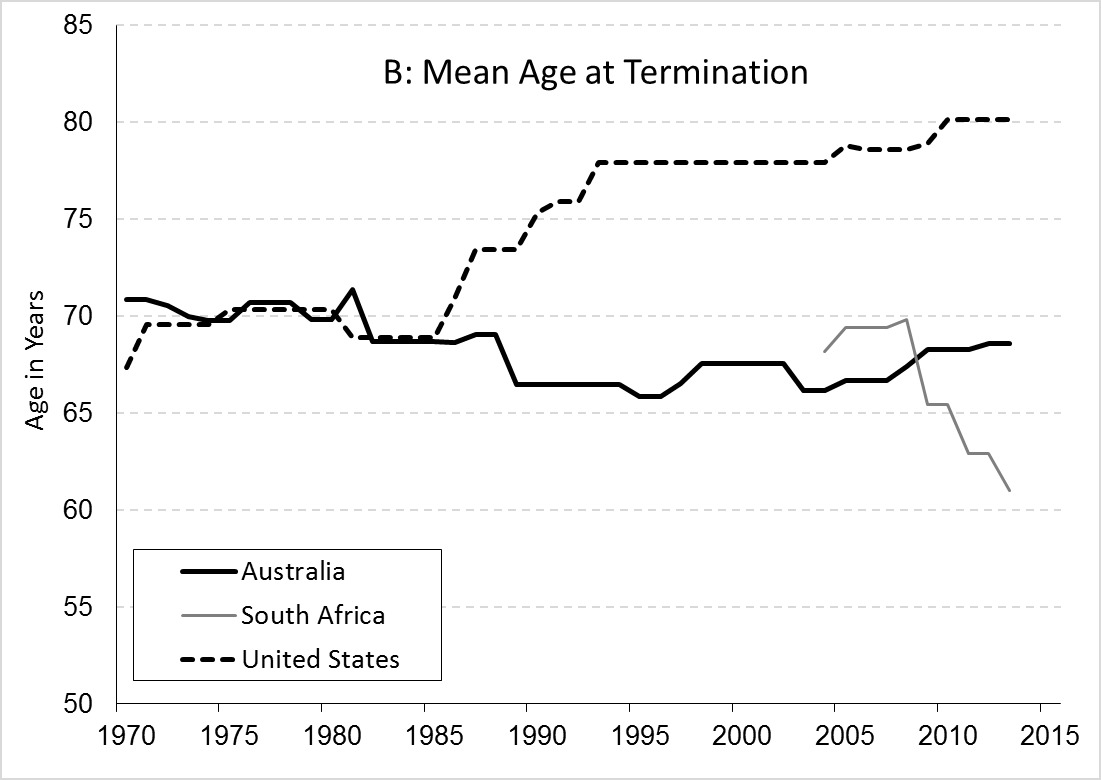

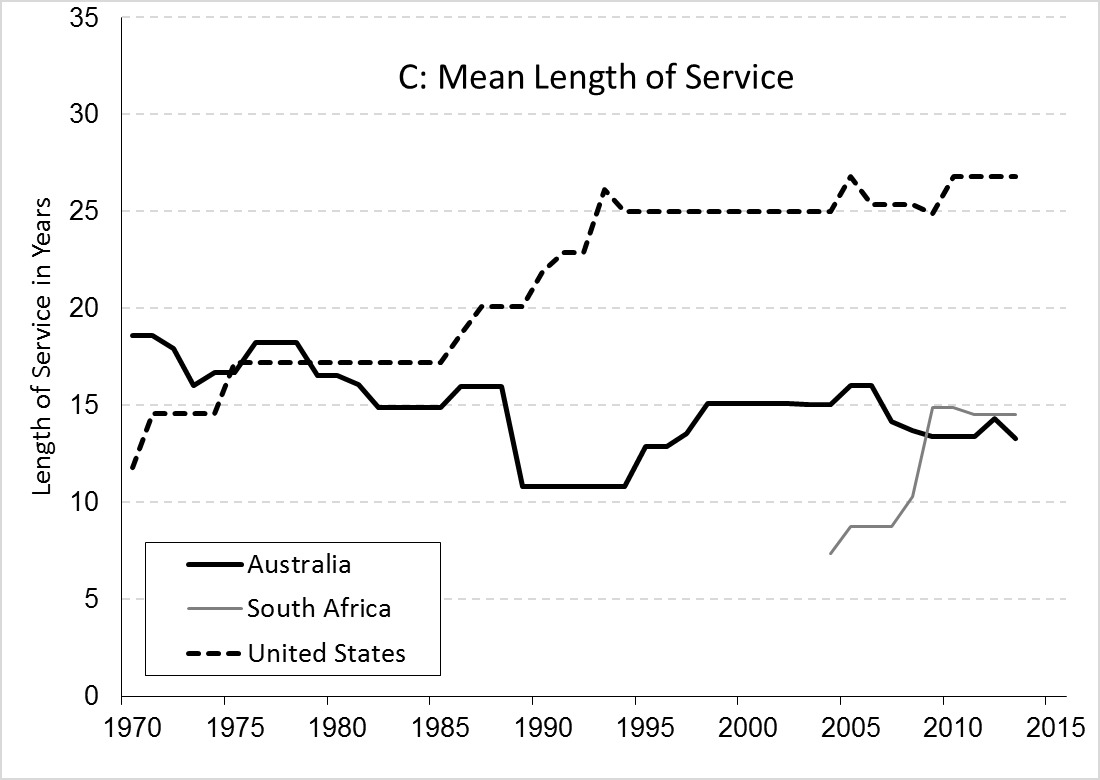

A novel feature of this article is that it provides a comparative empirical assessment of the tenure practices of the selected courts by examining changes over time in the judges’ age at appointment, age at termination and length of service. There is considerable similarity in the mean age at appointment in the three courts but there are stark differences in the other variables. In recent years, justices of the Supreme Court, who enjoy life tenure, have served on average 10 years longer, and to much older ages, than justices of the High Court or the Constitutional Court.

The courts selected for this study are paradigms that reflect a broad span of constitutional practice but they do not exhaust that practice. It is sometimes suggested that the tenure of judges should depend on an assessment of their continuing ability to perform judicial work to the requisite standard as they age.[4] These proposals derive their force from the argument that individual capacity assessment or competence testing is superior to the imposition of a blanket rule of compulsory retirement because the latter ‘fails to account for the differing capacities of individuals at older ages, reinforces stereotypes about the abilities of mature age workers and reduces utilisation of the workforce contribution of mature age workers’.[5] Whatever the merits of capacity assessment in the general workforce, its application to judges is problematic because of the countervailing interest in immunising the judiciary from executive discretion, where such assessments might be reposed. Moreover, the ability to make reliable assessments of capacity in relation to the nuanced cognitive activity of judging is doubtful. This article does not discuss this model of tenure.

The argument is organised as follows. Part 2 examines the changing social context in which judicial tenure must now be assessed. Then, commencing with the historical antecedents of judicial tenure under the Stuart Kings, Part 3 discusses the constitutional framework for regulating judicial tenure in three courts that exemplify the use of life limits, age limits and term limits in common law adjudication,[6] where greater demands on the creativity of judges place a premium on their independence. Part 4 turns to the empirical record and considers how different models of tenure are reflected in the experience of the courts with regard to age at appointment, age at termination and length of service. Part 5 explores how the problems inherent in the constitutional models have been ameliorated by legislative intervention. In the United States, these interventions have sought to encourage life-tenure judges to exit early; in Australia they have sought to encourage mandatory retirees to return to the bench as acting judges; and in South Africa they have sought to encourage judges to stay longer in their positions. Part 6 examines the tensions that inhere in different models of tenure through the lens of five dyadic relationships, namely, judicial independence versus accountability; constancy versus change in the composition of the bench; cost versus effectiveness; rigidity versus flexibility in the level of regulation; and the contrast between courts at different levels of the hierarchy or invested with different subject matter jurisdiction. Part 7 concludes that the choice between models, and between key parameters within each model, reflect complex policy preferences. Hybrid arrangements that incorporate age limits and term limits—illustrated by the experience of the Constitutional Court of South Africa—provide an appropriate compromise between competing policy objectives.

2. Changing Social Facts

The plurality of constitutional practice with respect to judicial tenure reflects the growing complexity of the social environment in which legal policy is formulated. While the relevance of judicial independence has not diminished, the social facts against which that principle operates have changed. Three changes merit attention—the marked rise in human longevity; the corresponding exposure of incapacities associated with senescence; and changing attitudes towards age-based discrimination.

A. Increasing Longevity

The developed world has experienced dramatic improvements in human longevity since the Industrial Revolution. In 1701, when life tenure for judges was first adopted in England as a matter of regular constitutional practice, life expectancy was only 37 years, and this barely changed over the next 150 years.[7] Today the life expectancy at birth for both sexes combined is around 79 years in the United States and 82 years in Australia, and by 2100 this is projected to rise to 89 years and 93 years, respectively, adding a whole decade to the average life span. South Africa has not fared as well due in part to the HIV/AIDS epidemic,[8] but life expectancy is still expected to improve from the current level of 57 years to 78 years by the end of the century.[9] These gains are attributable to better hygiene, sanitation, medical practice and pharmacology, and are part of an epidemiological transition in which humans have progressed in stages from an ‘age of pestilence and famine’ to an ‘age of degenerative and man-made diseases’.[10]

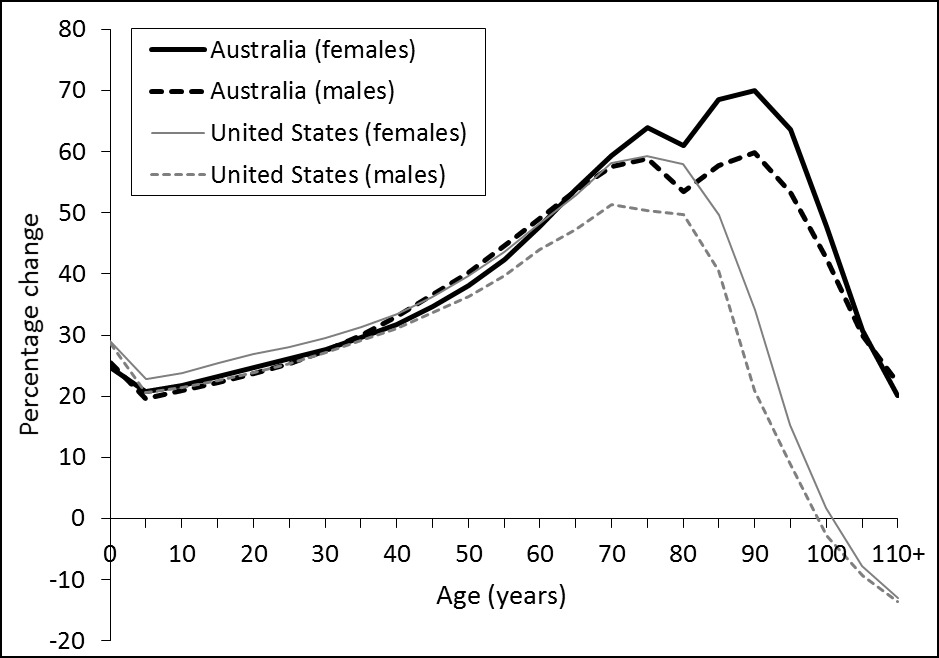

For the present study, a more significant statistic is life expectancy at the average age of judicial appointment, which is around 50 years of age, depending on the court. In 2005–2010, a judge appointed at age 50 could expect a total life span of 81.1 years in the United States, 83.6 years in Australia and 70.8 years in South Africa.[11] These figures exceed life expectancy at birth because a person who reaches the age of judicial appointment has already survived the vicissitudes of life for many decades, including the first year of life, which is the most perilous. Examined from another perspective, a large proportion of the ongoing improvements in life expectancy comes from reductions in the mortality of males and females in their senior years.[12] This can be seen in Figure 1, which shows the percentage improvement in life expectancy at different ages in Australia and the United States over the period 1933–2009 (for which data are readily available). The graph demonstrates that life expectancy has improved in both countries for all ages (except the extremely old in the United States), but the largest improvements have come from those aged 50–90 in the United States and those aged 50–100 in Australia. In general, the improvements have been greater for females than males, and better for Australians than for United States residents.

Figure 1: Percentage Improvements in Life Expectancy by Age, Sex and Country, 1933–2009

Source: Author’s calculations using Human Mortality Database, University of California, Berkeley (USA), and Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research (Germany). Available at www.mortality.org or www.humanmortality.de.

There are many instances of judges serving well into old age, leading judge Richard Posner to the colourful observation that the United States judiciary is ‘the nation’s premier geriatric occupation’.[13] For example, in the United States Federal District Court, Judge Wesley Brown died in office in 2012 at age 104, having served nearly 50 years on the bench, making him both the longest serving and oldest federal judge still hearing cases at that date. A list of the longest serving federal judges records 191 individuals who have served more than 40 years on the bench since 1789.[14] In Australia too there are examples of judges serving well into their eighties—records that were set in the era, now passed, in which appointment was for life.[15]

The fact of declining mortality has the potential to impact all models of judicial tenure—judges appointed for life have the potential to serve substantially longer terms; judges appointed to a fixed age are likely to have longer periods in retirement; and judges appointed for fixed terms are likely to have longer periods of their productive working lives in non-judicial roles.

B. Productivity and Decrepitude

One of the sequelae of increased life expectancy is that the frailties of human ageing are exposed to public view in circumstances that were often masked when life was ‘brutish and short’.[16] One frailty is that productivity in working life generally declines with advanced age—especially when problem solving, learning and speed are required job attributes.[17] According to the life-cycle model of human capital accumulation, productivity initially increases during a learning phase, then peaks, and finally falls as investment in skills declines in older ages.[18] It has been suggested that judges are an exception to this pattern and that they perform ‘creditably and indeed sometimes with great distinction at advanced ages’.[19] Moreover, age-related declines in productivity can be ameliorated in appellate courts by the collegiate behaviour of judges, such as sharing the burden of producing written reasons through joint judgments.[20] Yet empirical studies of superior courts support a life-cycle hypothesis in which judges exert less influence as they get older. Measured by the number of times a judge’s decisions are cited in later cases (which has been taken as a proxy for the quality of judicial output), the productivity of High Court and Federal Court judges in Australia has been shown to peak when judges are in their sixties and then decline with age until retirement.[21]

A more serious problem is that an ageing bench may not only be less productive but may become susceptible to incapacitation through senescence. In a pioneering study of ‘mental decrepitude’ on the United States Supreme Court, David Garrow concluded that ‘historical evidence convincingly demonstrates that mental decrepitude among aging justices is a persistently recurring problem that merits serious attention’.[22] Noting that the Twentieth Century featured 11 Supreme Court justices whose declining mental capacity should have led to earlier departure, Garrow advocated a constitutional amendment to impose mandatory retirement for justices at age 75. Without that barrier, judges might continue to adjudicate into old age because, as Posner has remarked, ‘judging is light work [and] senility is virtually the only condition short of death that disables a judge from performing at a satisfactory although not necessarily distinguished level’.[23]

Garrow’s account is unusual for its depth of treatment of a sensitive subject that is largely unrecorded. Documentation of judicial infirmity is often confined to examples in judicial biographies and snippets in legal miscellanea. As with all inductive reasoning, it is not possible to derive definitive generalisations from these particularised accounts, yet anecdotes abound. One well-documented example concerns Australia’s youngest appointee to the High Court, H V Evatt, who left that office in 1930 at the age of 46 to pursue a career in national politics. Twenty years later, when he was ‘far removed from the practice of law and already showing signs of mental deterioration’, he was made Chief Justice of New South Wales.[24] However, he was unable to function at the most basic level—he was unfocussed, had no grasp of the cases at hand, and relied on others to write his judgments. Ultimately, he was encouraged to resign and spent his remaining years in a ‘regressed state under the care of his wife and a nurse’.[25]

The manner in which age affects productivity and decrepitude has a bearing on the merits of life limits and age limits as models of judicial tenure. The prospect of mental incapacity raises concerns about life tenure and provides a yardstick for determining an appropriate retirement age if mandatory retirement is adopted.

C. Age Discrimination

The third social change is the shift in public attitudes towards ageing and age-based discrimination. Term limits are an age-neutral model of tenure because the duration of a judge’s appointment is unrelated to his or her chronological age. Life tenure is a pro-ageing model of tenure because it implicitly assumes judges have full capacity to discharge their functions until their death or earlier voluntary retirement, even if this entails service into extreme old age. By contrast, age limits embody an ageist conception of tenure because judges cease to hold office on reaching the mandatory retirement age regardless of their individual capacities. The presumption of ‘statutory senility’, as mandatory retirement is sometimes called, is the price paid for avoiding the risk of judicial over-stayers.[26] As a House of Lords Select Committee noted in 2012, ‘A set retirement age is undoubtedly a blunt tool by which to assess whether someone is no longer fully capable of performing their job.’[27] It is this model of tenure that most significantly challenges societal views of age discrimination.

How have legal attitudes towards ageing workers changed over recent decades? Despite the burgeoning of human rights norms of equality and non-discrimination in the United Nations era, discrimination on the basis of age has been comparatively underdeveloped at the international level. The reasons are not hard to fathom. The arguments for strict scrutiny of discrimination on the grounds of age are less compelling than for grounds such as race or sex because nearly everyone experiences the cycle of youth and ageing, with its concomitant stereotypes.

While concern for individual rights may not have been the driving force behind the prohibition of age discrimination, countries have responded to anxieties about their macro economies. Many countries now recognise that their populations are ageing inexorably due to declining fertility and increasing longevity. As the proportion of the older population continues to rise, many economies will face declining labour force participation rates and reduced growth unless they can retain the skills of older workers.[28] There is a broad consensus that ‘policies that remove barriers to employment and enhance the productivity of older men and women are an essential part of any effective response to population aging’.[29] These concerns underpin the legislative prohibition of age discrimination in employment in the United States, Australia and South Africa (where there is also constitutional protection). The upshot is that mandatory retirement has been all but abolished for most public and private employees.

Should judges be subject to mandatory retirement laws that do not apply to the public at large? At the macro level, judges form a minute segment of the economy and their exclusion from a general prohibition on mandatory retirement is of little economic consequence. A more compelling argument is that judges as individual are the bearers of rights and are entitled to be free from age discrimination. Yet this right is not absolute, as is recognised in the exemption of some occupational classifications from general statutory protections.[30] It must thus be asked whether the state’s interest in ensuring the proper administration of justice through the retention of only the most able judges justifies a mandatory retirement rule whose application may be over-broad in particular instances.

3. Four Models of Judicial Tenure

Constitutional history reveals four core models of judicial tenure in Britain and its erstwhile dominions. The earliest was the model in which judges held office at the discretion of the executive and could be dismissed at whim. This discretionary model is the antithesis of judicial independence and bears the institutional risks of bias in decision-making, erosion of public confidence in the judiciary, and (for non-compliant judges) a tenuous grasp on office. When the worst excesses of the Stuart Kings generated pressure for reform at the end of the Seventeenth Century, the discretionary model gave way to the regular practice of appointing judges for life. This model has endured in many countries whose constitutional systems evolved from the United Kingdom. Life tenure provides a very high degree of independence because a judge is largely placed beyond the reach of the executive’s opprobrium from the moment of appointment. However, some of the difficulties that are inherent this model were masked by the short life expectancy of appointees in those times. A life tenure judge who is disinclined to retire may hold office into extreme old age and this too may adversely affect public confidence in the judiciary if the judge lacks capacity to decide cases according to law. In the Twentieth Century and beyond, modern democracies experimented with other models of tenure, including mandatory retirement at a specified age and appointment for a fixed term.

A. The Whimsy of the Stuart Kings: Executive Discretion

England was a turbulent place in the Seventeenth Century—riven by war with other nations, clashes between the monarch and Parliament, and theological conflict between Catholicism and Anglicanism. In the legal world, this heady mix gave rise to a transformation in constitutional practice from judges holding office during the King’s pleasure (quam diu nobis placuerit) to judges holding office during good behaviour (quam diu se bene gesserit), but the transition was neither rapid nor smooth.[31]

Before 1641 the letters patent issued by a monarch when conferring judicial office nearly always stated that the office was held during the King’s pleasure. This allowed a judge to be dismissed at will, without cause. In practice this arrangement caused little difficulty because the King and the Parliament worked together harmoniously. It was not until the courts were implicated in the struggle for power between the executive and the legislature that their independence became important.[32] There followed an unsettled period in which the predilections of the monarch resulted in some judges being appointed during pleasure and others during good behaviour. The worst excesses of monarchical power occurred under the Stuart Kings,[33] whose transfer and removal of troublesome judges made some ‘pretty black pages of history’.[34] In the last 11 years of his reign, Charles II dismissed 11 of his judges; while his brother James II dismissed 13 judges in four years, including four in one day.[35] A particular source of conflict was James II’s plan to re-Catholicise the country by appointing Catholics to important public positions. When the judges declined to support the King’s attempt to dispense with laws that barred Catholics from holding public office, the judges were summarily dismissed.[36]

The discretionary model of judicial tenure did not long survive the Glorious Revolution. Dissatisfaction with the capricious actions of the King eventually led Parliament to limit the royal prerogative through the Act of Settlement 1701. Its critical contribution to bolstering judicial independence was a provision stating that ‘Judges Commissions be made quam diu se bene gesserint [during good behaviour] and their salaries ascertained and established but upon the Address of both Houses of Parliament it may be lawful to remove them.’[37]

The enactment created two channels by which a judge’s tenure might be brought to an end: first, where a judge ceased to be of good behaviour and thus failed to fulfil the conditions of the letters patent; and second upon a joint address of the Houses of Parliament without any cause shown. Removal on the former ground was a matter for the Crown but it was a substantial advance on holding office at pleasure because it involved the safeguard of proceedings before a court (on a writ of scire facias) in which the judge could show cause why the letters patent should not be revoked. Removal on the latter ground, although permitted for any reason, established an elaborate procedure that Parliament was reluctant to invoke. Since 1701 this procedure has been used only once in the United Kingdom—in 1830 to remove an Irish judge who had been found guilty of embezzlement[38]—leading one writer to suggest that there may now be a convention against invoking the address procedure except in the most flagrant or extreme cases of judicial incapacity.[39]

B. Til Death Us Do Part: Life Tenure in the United States

Life tenure became the standard practice for judicial appointments in England after the Act of Settlement, and a model for other legal systems that looked to English constitutional history for guidance. Although that model has not endured in the United Kingdom itself—where judges appointed to higher courts since 1959 have been required to retire at age 75, and those appointed since 1995 at age 70[40]—the influence of the Act of Settlement on the common law world cannot be gainsaid. Thus it was that Art III s 1 of the United States Constitution provided that federal judges ‘shall hold their Offices during good Behaviour’, while Art II s 4 made provision for judges to be removed from office by impeachment for ‘Treason, Bribery, or other high Crimes and Misdemeanors’.

Writing in support of Art III s 1 during the ratification period, Alexander Hamilton advanced several reasons for preferring life tenure over ‘temporary commissions’.[41] Permanency in office not only comported with the best practice of state constitutions of the day and the ‘illustrious’ experience of Great Britain but contributed so much to ‘that independent spirit in the judges which must be essential to the faithful performance of so arduous a duty’. Hamilton was particularly ardent in his criticism of age limits for federal judges. Rejecting the approach in the New York Constitution of taking a particular age (60 years) as the ‘criterion of inability’, he argued that a judge’s ‘deliberating faculties’ preserved their strength well beyond that age, and that very few men outlived ‘the season of intellectual vigor’.[42]

The life tenure model that was adopted for federal judges, and continues to this day, is no longer widely embraced at the state level, where 32 of 50 states now have mandatory retirement ages entrenched in their constitutions or legislation for at least some state judges,[43] often overlaid by a pastiche of mechanisms for selection or retention through popular election.[44] The constitutionality of mandatory retirement laws has been challenged under the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment on the ground that they are discriminatory, but the Supreme Court has consistently upheld them.[45]

C. Constitutional Senility: Age Limits in Australia

The third model of tenure is one in which judicial office expires when the judge attains a specified age. Age limits have a substantial pedigree and are used in many countries at all levels of the judicial hierarchy. This section examines their adoption in the Australian Constitution, which regulates the federal judiciary, and compares this with the practice in the constituent states of the federation.

The Australian Constitution was modelled closely on the United States Constitution. Yet, in respect of judicial tenure, differences emerged with successive drafts as the Australian founders sought to strengthen judicial independence by circumscribing the situations in which a judge could be removed from office. The key provision is s 72, which, as enacted, contemplated only one mode of termination. It provided, and still provides, that federal judges ‘shall not be removed except by the Governor-General in Council, on an address from both Houses of the Parliament in the same session, praying for such removal on the ground of proved misbehaviour or incapacity’.

However, s 72 failed to specify the tenure of federal judges—it made no express mention of holding office during good behaviour but only provided for removal. This uncertainty was not resolved for many years. In Alexander’s Case[46] the High Court considered the validity of the appointment of the President of the Commonwealth Court of Conciliation and Arbitration. The Court was established in 1904 as a new federal court to hear and determine industrial disputes, but its President was appointed only ‘during good behaviour for seven years’, with the possibility of reappointment. A majority of the High Court held that the appointment was invalid because, under s 72, every judge of a court created by the Parliament is required to be appointed for life, subject only to the power of removal on the grounds of ‘proved misbehaviour or incapacity’. For Isaacs and Rich JJ, it was ‘plain that the independence of the tribunal would be seriously weakened if the Commonwealth Parliament could fix any less permanent tenure than for life’—a claim that might now be challenged in light of the experience of other courts with age limits and term limits.

The original text of s 72 remained the basis of judicial tenure for federal judges for the next 60 years, notwithstanding major reviews of the Constitution in 1929 and 1959. However, in 1977 a Senate Committee conducted an inquiry into the tenure of federal judges,[47] prompted by parliamentarians who were shocked at being sworn into office by an aged and feeble Acting Chief Justice.[48] The Committee’s recommendations became the basis of a constitutional referendum to introduce a mandatory retirement age for federal judges. For justices of the High Court this was to be 70 years of age; for judges of other federal courts, 70 years was to be the maximum age but Parliament could set a lower limit if it chose to do so. Faced with bipartisan support for the referendum proposal, voters gave it their overwhelming endorsement: the referendum passed in all states and was approved by over 80 per cent of the population.

The Government’s rationale for proposing the constitutional amendment can be seen in the second reading speech made in Parliament when introducing the relevant Bill.[49] In the opinion of the Attorney-General there was an almost universal practice that holders of public office retire on attaining a maximum retirement age.[50] He noted that a fixed retirement age had been adopted in all state Supreme Courts and that it was appropriate to make similar provision for the growing number of federal judges. The issue became a live one from the mid-1970s as the Australian Parliament began to create new federal courts, invest them with jurisdiction, and appoint judges to hear and determine the new matters.[51] Perhaps more revealing are the comments made during the parliamentary debate, namely, that judges are not immune from the geriatric processes of mental decay, and that the proposed age limit would lead to a younger body of judges who are ‘closer to the people’ and have ‘current day sets of values’.[52] These views echo the efforts of the Lord Chancellor to modernise the English judicial system in the 1950s, including by introducing mandatory retirement, when it was said that judges had until then been allowed to continue ‘in a job which requires the keenest faculties at an age when other men are deemed suitable only for some gentle gardening’.[53]

The notion that there should be a mandatory retirement age for federal judges appears to have been quickly accepted but there was virtually no discussion of the appropriateness of selecting 70 years as the maximum age. For example, it passed unremarked that the United Kingdom had set a retirement age of 75 years for judges of higher courts nearly 20 years before.[54] Even the report of the Senate Committee said little on the subject, noting only that 70 was the ‘retiring age most commonly established for judges of State and territory Supreme Courts’.[55] The desire for conformity between state and federal practice was conspicuous. New South Wales was the first state in Australia—and one of the first jurisdictions in the British Empire—to introduce a mandatory retirement age for judges of superior courts when it legislated during the First World War.[56] The law was the ‘product of a unique time’ in which there were persistent ‘unfriendly relations between the government and the judiciary’.[57] A significant motivation for the change appears to have been the desire to terminate the office of specific judges. The retirement age was set at 70 years with a passing reference to the biblical lifespan of ‘three score and ten years’.[58] The choice proved influential and other states followed with constitutional or statutory amendments. Today, 70 years remains the mandatory retirement age for judicial officers in all states except in New South Wales and Tasmania, where it has since been increased to 72 years,[59] and in magistrates’ courts in Western Australia and the Australian Capital Territory, where it is 65 years.[60]

D. Term Limits in South Africa

A fourth model of tenure is one in which a judge’s term has a fixed duration and thus comes to an end by effluxion of time. This mode of termination is used in a large number of countries. It is especially prevalent in constitutional courts that follow the civil law tradition where constitutional review is concentrated in a specialised court to the exclusion of other courts, in contrast to the common law tradition where constitutional review is diffused throughout the courts of the land. The progenitor of the specialised model was the Austrian Constitutional Court established in 1920,[61] but specialisation became a typical feature of constitutional review in Continental Europe after the Second World War and proliferated further with the collapse of communism.[62] However, the term limit varies widely, from 6 years in Niger and Portugal to 12 years in Germany, Hungary, Slovakia and Turkey.[63]

This section focusses on the evolution of term limits in the Constitutional Court in South Africa, where a new court was established to adjudicate sensitive constitutional questions in the post-apartheid era, free from the taint of complicity in a ‘wicked system’ that infected the judiciary in the apartheid years.[64] Its utility as a case study is not dependent on the specialised nature of constitutional review, which was difficult to maintain from its inception[65] and has now been formally abandoned,[66] but rests on its practical illustration of one particular model of judicial tenure. In South Africa, that model applies only to justices of the Constitutional Court (see Part 6(E) below).

South Africa’s 1993 interim Constitution established a Constitutional Court comprising a President and ten other members, and invested it with jurisdiction over all matters relating to the interpretation, protection and enforcement of the Constitution. The members of the Court were to hold office for a non-renewable period of seven years, which would take their service beyond the life of the interim Constitution and the first Parliament.[67] For those involved in negotiating the interim Constitution, the limited terms were thought appropriate for judges of the top court, which was to exercise substantial political authority through its constitutional mandate.[68] In 1994, a President and ten other judges were duly appointed to the Constitutional Court. To provide balance between continuity and change,[69] four judges had to be appointed from the ranks of existing judges, and this remains a requirement today.[70]

Important changes were made to tenure arrangements by the adoption of the final Constitution in 1996. Under s 176(1), a Constitutional Court judge was to be appointed ‘for a non-renewable term of 12 years, but must retire at the age of 70’. The two new features—longer fixed terms coupled with mandatory retirement at age 70—were modelled on Germany’s Federal Constitutional Court whose judges hold office for 12 years, without the possibility of re-election, but subject to mandatory retirement at age 68.[71] Reflecting on the rationale for term limits, Kate O’Regan, a judge of the South African Constitutional Court from 1994 to 2009, remarked that ‘It is unfortunate if a senior court turns over in membership too quickly, but it is doubly unfortunate if it turns over too slowly. Our (effective) 12-year term limit steers a course between these evils.’[72] This issue is reprised in Part 6(B).

The tinkering with the tenure arrangements did not end with the passage of the 1996 Constitution. In 2001, s 176(1) of the Constitution was amended to give a new role to the legislature.[73] The subsection now reads: ‘A Constitutional Court judge holds office for a non-renewable term of 12 years, or until he or she attains the age of 70, whichever occurs first, except where an Act of Parliament extends the term of office of a Constitutional Court judge.’ The change effected by the final clause is the addition of a legislative power to extend judges’ terms by relaxing either the 12-year term limit or the 70-year age limit, or both.

Parliament wasted no time in exercising its new power. In 2001 it altered both the term limit and the age limit, albeit in complex ways.[74] The 2001 Act affirms the 12 year term limit and 70 year age limit as alternative criteria for departure from the Court, but there are circumstances in which a judge may be required to serve on the Constitutional Court for 15 years or to age 75. For example, under s 4(1), if a judge’s 12 year term on the Constitutional Court expires before he or she has completed a total of 15 years’ active judicial service (as would occur if the appointee had not previously held judicial office, or had previously served on another court for less than three years), then the judge must continue to serve on the Constitutional Court until completing 15 years’ service. Similarly, under s 4(2), if a judge attains age 70 before he or she has completed a total of 15 years’ active judicial service (as would occur if the judge were older than 55 years at appointment), then the judge must continue to serve on the Court until completing 15 years’ service or attaining age 75, whichever comes first. These statutory provisions have to conform to the constitutional right to equality and to the prohibition against unfair discrimination on the ground of age,[75] but to date the courts have not considered the constitutionality of mandatory judicial retirement.

4. The Empirical Record

The optimal design of constitutional provisions and cognate legislation regarding judicial tenure requires a clear understanding of how the contrasting models operate in practice. Unfortunately, little attention has been paid to empirical evidence outside the United States, leaving many key questions unanswered. This Part seeks to fill that gap by examining available data on each of the three chosen courts.

The information needed for the analysis is straightforward: for each judge appointed to a court over a specified period one needs only their dates of birth, appointment and termination, from which one can deduce three key variables: age at appointment, age at termination and length of service at termination. Although the data required for the analysis are undemanding, they are surprisingly difficult to procure.[76]

A. Supreme Court of the United States, 1789–2013

In 2006, Steven Calabresi and James Lindgren undertook a path-breaking empirical study of tenure on the Supreme Court.[77] They found that there have been significant changes in the practical meaning of life tenure for justices of that Court, as evidenced in their length of service, age at termination, and the interval between vacancies. Comparing the 30 year period 1941–1970 with 1971–2006, the authors found that the justices’ mean length of service had more than doubled to 26.1 years compared with 12.2 years in the earlier period; the mean age at which justices left office had risen to 78.7 years compared with 67.6 years; and the frequency of vacancies had declined from an average of one every 1.6 years to one every 3.1 years.

They proffered several reasons for the observed changes—increasing longevity; an increase in the strategic timing of departures by justices to ensure their replacements were appointed by Presidents of the appropriate political persuasion; improvements in the social status of judges; and a lessening of the demands of the job due to reduced caseload and more staff. In their view, there were three vices in the emerging patterns of tenure. They reduced democratic control over the Supreme Court by making appointments infrequent and irregular, thus limiting ‘the democratic instillation of public values on the Court through the selection of new judges’.[78] They made the Senate confirmation process more political, to the point of dysfunction, because the irregular occurrence of vacancies made the stakes so high. And they resulted in an increasing prevalence of mental decrepitude on the Court as justices stayed for longer periods and to more advanced ages. The authors considered these trends to be sufficiently serious to warrant a constitutional amendment to abandon life tenure in favour of term limits.[79]

For the purpose of comparative analysis, this article applies Calabresi and Lindgren’s methodology to data on the Supreme Court, but it updates the analysis to 30 June 2013 and incorporates more detailed data on age at appointment. This study also adopts an improved graphical representation based on a true temporal scale, which is necessary if comparisons are to be made between ages of appointment and termination, and between jurisdictions.[80]

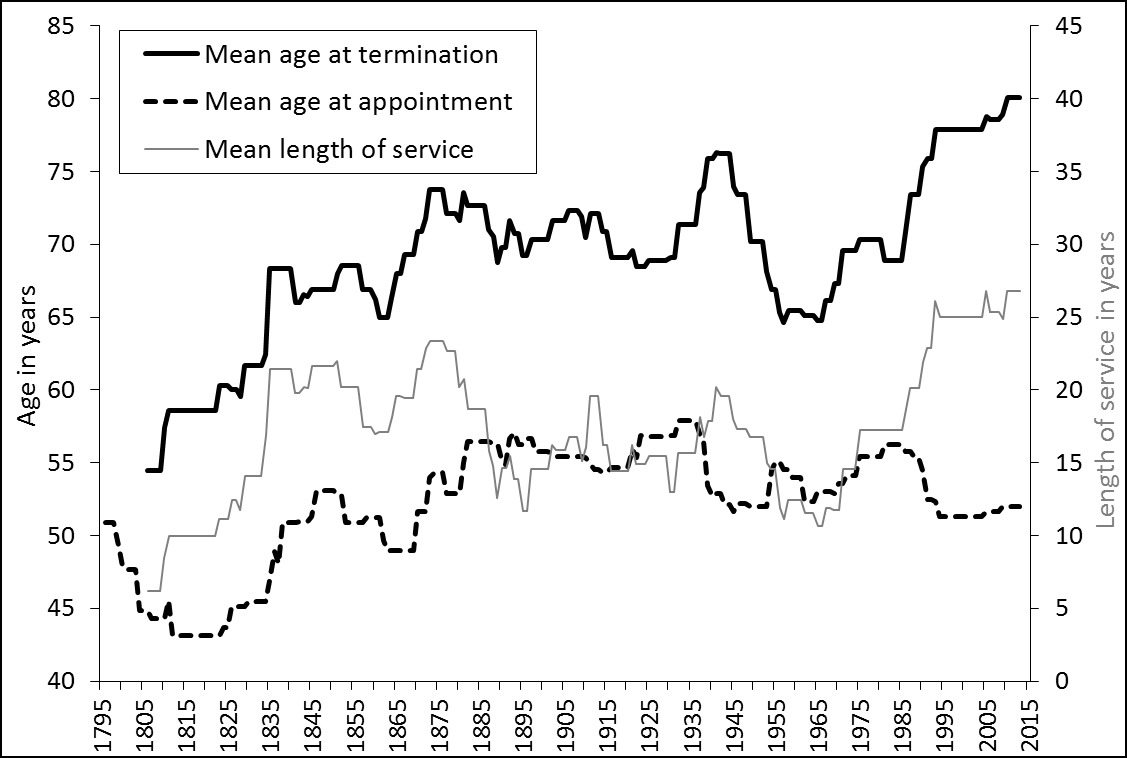

Since the Supreme Court was established in 1789, 112 justices have been appointed to it (as at 30 June 2013), of whom nine are incumbent and the remaining 103 have ceased to hold office. The average age of appointees is 52.5 years, with the youngest being appointed at 32 years and the oldest at 65 years. Figure 2 plots the mean age at appointment, calculated as a moving average of the past nine appointments, commencing in 1796 when the Court experienced its ninth appointment. The mean age of appointment was relatively low in the early Nineteenth Century, but this had stabilised by the Twentieth Century to the range of 54–56 years, and in the past 20 years to the range of 51–53 years.

Figure 2 also plots the mean age at termination (left hand axis) and the mean length of service (right hand axis) of the 103 associate justices and chief justices whose appointments have now terminated. The means are calculated as a moving average of the past nine terminations, commencing in 1806 when the Court experienced its ninth termination. The graph shows that the mean age at termination rose markedly from around 54 years in the Supreme Court’s early years, to 76 years in the 1940s, before falling dramatically in the 1950s and 1960s. Since then there has been an unprecedented rise in the mean age at termination to its current historic high of 80.1 years. Given the relative stability in the mean age of appointment, not surprisingly the trend in age at termination is echoed in the mean length of service, which in 2013 was also at an historic high of 28.8 years. Over the entire history of the Supreme Court, the mean age at termination is 69.6 years and the mean length of service is 17.0 years (excluding current members).

Figure 2: Appointment, termination and length of service, US Supreme Court

Source: Lee Epstein et al, The U.S. Supreme Court Justices Database (2 March 2013) <http://epstein.usc.edu/research/justicesdata.html> .

B. High Court of Australia, 1903–2013

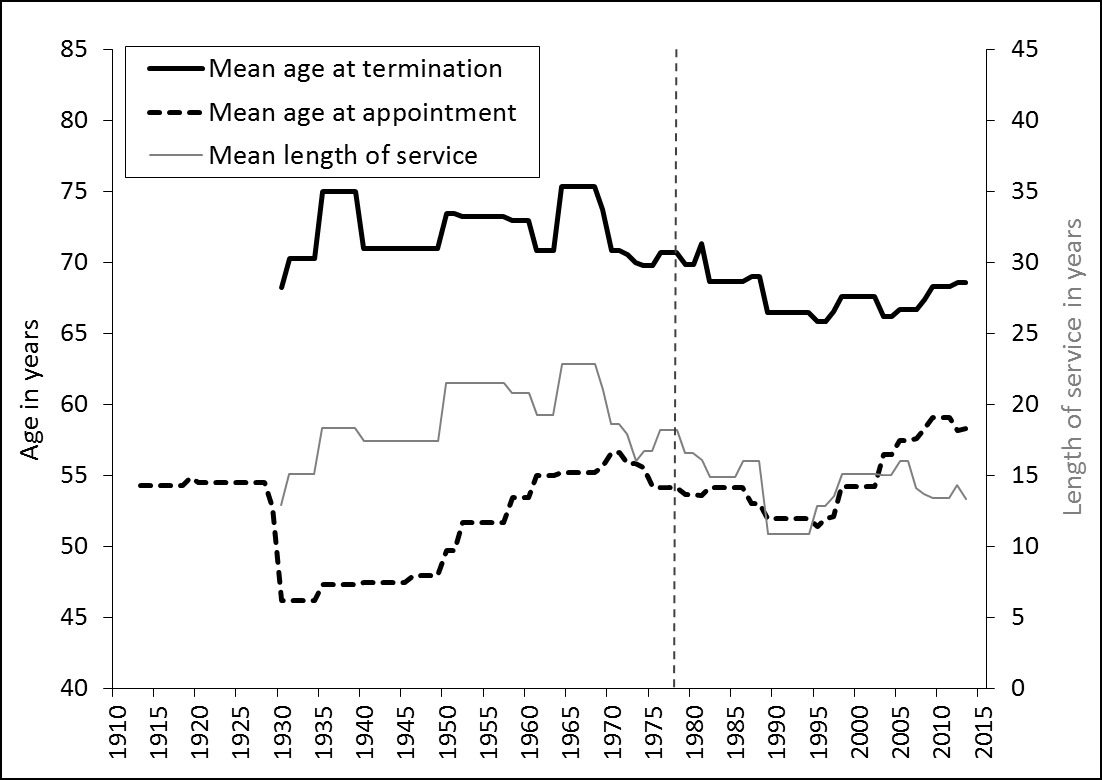

Since the High Court was established in 1903, 50 justices have been appointed to the Court (as at 30 June 2013), of whom seven are incumbent and the remaining 43 have ceased to hold office. We again examine age at appointment, age at termination and length of service using the methodology applied to the Supreme Court.[81] The mean age of appointees is 54.1 years, with the youngest being appointed at 36.6 years and the oldest at 61.8 years. Figure 3 shows a significant drop in the mean age of appointment around 1930, when the two youngest appointees in the Court’s history took office in quick succession (Evatt J was 36, and McTiernan J was 38). The impact of these atypical appointments lessened over time, and a period of stability followed in the 1960s to 1980s. Since 1995 there has been a rise in the mean age at appointment from 51.4 years to 58.3 years, reflecting the recent tendency to appoint individuals who have had substantial judicial experience on other courts, and who are necessarily older when appointed to the High Court.

Figure 3 also plots the mean age at termination (left hand axis) and the mean length of service (right hand axis) of the 43 justices whose commissions have now terminated. The graph shows that until the 1970s the mean age at termination was persistently above 70 years, despite the fact that life expectancy was much lower in the first half of the Twentieth Century. Once the age limit of 70 was introduced in 1977 (indicated by the dashed vertical line), the mean age at termination began to fall before recovering in recent years to 68.6 years. There is a clear visual correlation between this series and the mean length of service, which was persistently above 15 years until the 1970s (peaking in the 1960s at 22.9 years), but has fallen to 13.3 years for the last seven terminations. Over the entire history of the High Court, the mean age at termination is 69.4 years and the mean length of service is 15.9 years (excluding current members).

Figure 3: Appointment, termination and length of service, High Court of Australia

Source: Michael Coper, Tony Blackshield and George Williams (eds), Oxford Companion to the High Court of Australia (Oxford University Press, 2001); ConnectWeb, Who’s Who in Australia (Crown Content, 2013); High Court of Australia www.hcourt.gov.au/.

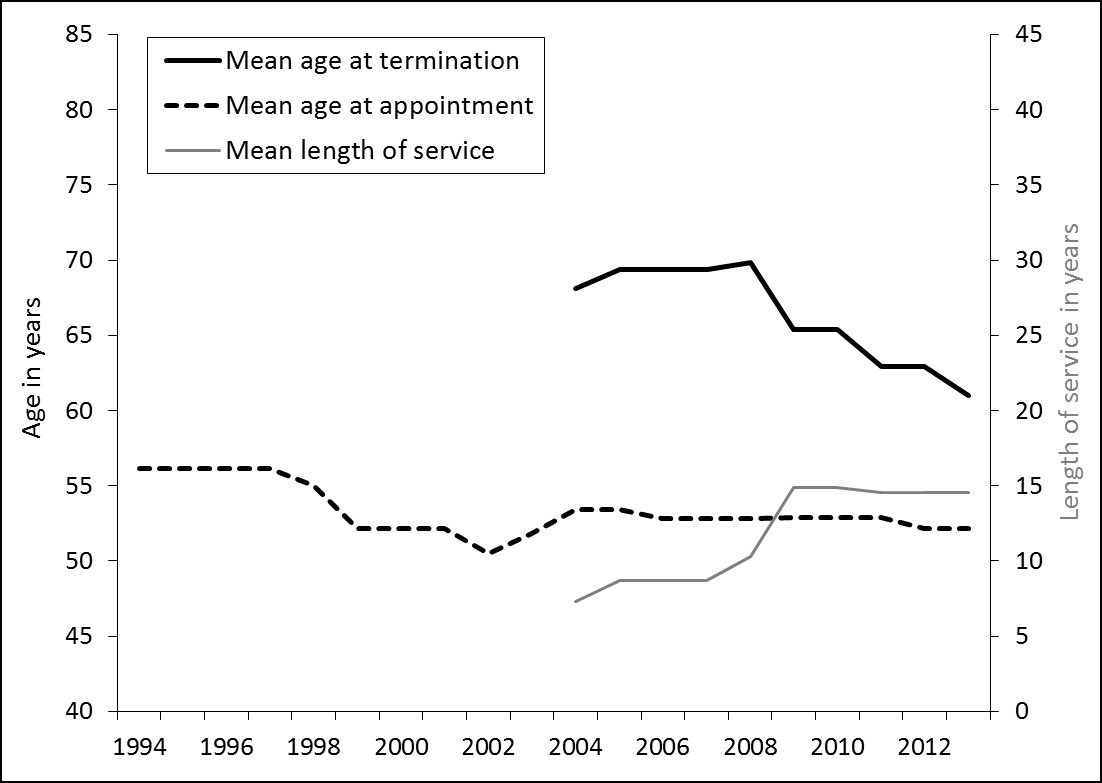

C. Constitutional Court of South Africa, 1994–2013

Since the Constitutional Court was established in 1994, 23 judges have been appointed to it (as at 30 June 2013), of whom 10 are incumbent and the remaining 13 have ceased to hold office.[82] The average age of appointees is 54.4 years, with the youngest being appointed at 36.8 years and the oldest at 64.0 years. Figure 4 plots the mean age at appointment using the same methodology as above,[83] and reveals remarkable stability in this variable over the past decade. Figure 4 also plots the mean age at termination (left hand axis) and the mean length of service (right hand axis) of the 13 justices and chief justices whose appointments have now terminated. Although caution is needed in interpreting the data because of the small population size, the graph shows that the mean age at termination was steady at around 70 years in the Court’s early years but has declined since 2008 to its current level of 61.1 years. Conversely, the mean length of service rose steadily in the early years from 7.3 years in 2004 and has plateaued at just under 15 years since 2009. In fact, all judges who departed the Court during its first decade served relatively short terms—less than 10 years—whereas those who have departed since then have served close to their maximum term of 15 years. This reflects the fact that appointees in the Court’s establishment phase were a highly diverse group of individuals who were on average older at appointment than their successors, and thus met the age limit of 70 years when their length of service was relatively short.

Figure 4: Appointment, termination and length of service, Constitutional Court of South Africa

Source: Constitutional Court of South Africa <www.constitutionalcourt.org.za>; Rapule Tabane and Barbara Ludman (eds), The Mail & Guardian A-Z of South African Politics (Jacana Media, 2009).

D. Comparative Assessment

What does the empirical record reveal about life limits, age limits and term limits in the three courts? Table 1 summarises key data, while Figure 5 re-presents the time series data in a way that aids visual comparison between the courts, focussing on the period since 1970. In interpreting the data it must be borne in mind that there have been intervening changes to the constitutional and legislative landscape with respect to tenure in each jurisdiction. In the United States, in 1984, judicial pensions were made available to federal judges at a younger age (see Part 5(A) below); in Australia, in 1977, an age limit of 70 years was introduced in lieu of life tenure; and in South Africa the term limit for judges of the Constitutional Court was increased from seven years (1993) to 12 years (1996) to 15 years in some cases (2001), subject to specific age limits.

Table 1: Summary Statistics: United States, Australia and South Africa

|

|

United States

|

Australia

|

South Africa

|

|

|

Supreme Court

|

High Court

|

Constitutional Court

|

|

Period

|

1789–2013

|

1901–2013

|

1994–2013

|

|

Membership

|

9

|

7

|

11

|

|

Appointment

|

|

|

|

|

Youngest

|

32 yrs

|

36.6 yrs

|

36.8 yrs

|

|

Oldest

|

65 yrs

|

61.8 yrs

|

64.0 yrs

|

|

Mean age

|

52.5 yrs

|

54.1 yrs

|

54.4 yrs

|

|

Number

|

112

|

50

|

23

|

|

Termination

|

|

|

|

|

Youngest

|

47 yrs

|

46.3 yrs

|

52.1 yrs

|

|

Oldest

|

90 yrs

|

87.0 yrs

|

74.4 yrs

|

|

Mean Age

|

69.6 yrs

|

69.4 yrs

|

66.5 yrs

|

|

Number

|

103

|

43

|

13

|

|

Length of Service

|

|

|

|

|

Shortest

|

1 yr

|

0.1 yrs

|

4.0 yrs

|

|

Longest

|

37 yrs

|

45.7 yrs

|

15.3 yrs

|

|

Mean duration

|

17.0 yrs

|

15.9 yrs

|

11.5 yrs

|

|

Number (completed service)

|

103

|

43

|

13

|

Source: As for Figures 2, 3, 4.

The first point of comparison is that there is marked similarity in the mean age at appointment, and in the age range of appointments, to the three courts (Table 1, Figure 5A). For appointments made in the period 1970–2013, the mean age is 53.1 (United States), 54.9 (Australia) and 54.4 years (South Africa). There has also been considerable stability in the age at appointment over time, except in Australia, where the mean age has risen since 1995 from early-fifties to late-fifties.

In contrast, there are significant disparities in the mean age at termination (Figure 5B). The Supreme Court and the High Court had similar experience in the period 1970–1985, when the mean age at termination hovered at around 70 years. For the High Court, the mean age at termination then declined in the period 1985–2010. This was not due to the introduction of mandatory retirement but to idiosyncratic factors affecting individual retirees, such as ill health and appointment to other offices. The mean age has since edged back towards 70 years because the past six terminations have all occurred at the mandatory retirement age. In the Supreme Court, however, there has been a relentless rise in the mean age at termination, which is now over 80 years—a full 11.5 years greater than the High Court. There is no ceiling to that rise other than the limits of human longevity itself. Interestingly, the rise in tenure has closely tracked improvements in longevity—between 1970 and 2010 the mean age at termination on the Supreme Court rose by 19 per cent, while life expectancy at age 50 (both sexes, all races) rose by 21.7 per cent.[84] In the Constitutional Court the mean age at termination was initially around 70 years (2004–2009) but has since fallen sharply to 61.0 years.

The patterns in mean length of service reflect the combined effect of changes in the mean age at appointment and the mean age at termination, as shown in Figure 5C. In the Supreme Court, the mean length of service has been 25 years or more every year since 1993. In the High Court, length of service has rarely exceeded 15 years over the same period, so that over the past 20 years (1994–2013) Supreme Court tenure has exceeded High Court tenure by an average of 11.3 years. In the High Court, the mean length of service has edged downwards in recent years because the mean age at appointment has risen while facing a fixed age limit of 70 years. In the Constitutional Court, the mean length of service has risen to just under 15 years, reflecting the rising term limits for some judges discussed above.

Figure 5: Appointment, termination and length of service in three courts, 1970–2013

|

|

Source: As for Figures 2, 3, 4.

|

5. Circumventing Constitutional Constraints

One of the functions of a written constitution is to be ‘an anchor in the past’, creating rules that bind ‘until a supermajority of the living changes them’.[85] This purposeful rigidity can create problems when the social facts upon which the rules were built cease to hold true. In the jurisdictions under examination, accommodations have been made to address these constitutional rigidities. In the United States, judges with life tenure have been encouraged to exit through generous retirement arrangements. In Australia, judges who have been forced to exit due to mandatory retirement have been encouraged to return as acting judges with short-term tenure. In South Africa, judges have been authorised to tarry longer through the extension of their term limits and age limits. In some cases, the desired flexibility has been achieved by overlaying constitutional rules with legislative provisions; in others, change has been made to the constitution itself. This Part examines creative solutions to some of the drawbacks of existing models of tenure.

A. Encouraging Exit: Incentives for Retirement in the United States

The drafters of the United States Constitution believed that life tenure was an appropriate model for the federal judiciary because the prospect of a ‘superannuated bench’ was an ‘imaginary danger’.[86] Today, the empirical record reveals legitimate grounds for concern, at least at the level of the highest federal court. Not only are Supreme Court justices departing at historically extreme ages but some are outliving their ‘season of intellectual vigor’ long before departure.

Yet these concerns are not new. A century after the life tenure model was adopted, Congress was alive to these issues and adopted two complementary measures to address them. In 1869 legislation was enacted to discourage federal judges from ‘remaining in office despite mental or physical infirmity’[87] by providing financial incentives for voluntary departure before death. A judge who had attained 70 years of age and completed 10 years’ judicial service could retire from office and receive a pension for life, equivalent to the judge’s salary at resignation. The heir of that provision remains on the statute books, although the qualifying conditions have changed. Since 1984, 28 USC §371(a) has stipulated the ‘Rule of Eighty’:[88] any federal judge aged 65 or more may retire from office on a lifetime pension if the sum of his or her age and years of service is at least 80—for example, age 65 with 15 years’ service, age 66 with 14 years’ service and so on.

Fifty years later a second reform was implemented, providing ‘a method of inducing retirement in a system in which mandatory retirement is unavailable’.[89] Since 1919 most federal judges have been able to take a form of qualified retirement—called senior service—in which they can work part-time and continue to receive a full judicial salary. The legislation initially excluded Supreme Court justices, but in 1937 they were brought within the senior service arrangements. As with the 1869 retirement provisions, senior service was initially available to judges who had attained 70 years of age and completed 10 years’ service. Today, 28 USC §371(b) allows a federal judge to ‘retire from regular active service’ if the Rule of Eighty conditions are met, so long as the judge performs a minimum of three months’ work a year. Senior service has become an increasingly attractive alternative to full retirement, for a mixture of personal and altruistic reasons.[90] Senior status judges continue to enjoy the stimulation of judicial work (or equivalent non-judicial work) with greater control over their caseload; they draw a full judicial pension that attracts significant tax concessions; and they retain their offices and staff; but they also create a vacancy on the court which can alleviate workload pressure for fellow judges.

Nevertheless, the changes in patterns of termination brought about by the senior service legislation have not been radical. In a study of departures from the United States Court of Appeals between 1919 and 1954, Richard Vining found that introducing qualified retirement did not make judges rush to leave the Court after their pensions vested (then at age 70); but it did make them ‘more willing to amble toward the exits’.[91] For the Supreme Court, the impact of these changes appears to have been significantly weaker, as borne out by the rising mean age at termination since 1985. For that Court, legislative attempts to discourage excessive service on the bench appear to have failed, leading one to ponder other solutions.

B. Encouraging Return: Post-Retirement Service in Australia

Australian courts face the contrary problem—how to retain the service of judges who have been forced to retire prematurely. As already noted, federal judges must retire at 70 and no person can be appointed as a federal judge if he or she has already attained that age.[92] Judicial service of any kind is thus impossible beyond age 70 within the federal judicial system. However, several Australian States recognise that their own mandatory retirement laws (which are not constrained by federal constitutional provisions) deprive their courts of fine talent, and they have enacted schemes to ameliorate the consequences of forced departure by appointing acting judges. In this way, retired judges of federal and state courts may return to render judicial service in their mature years within the state court systems, just as they have been used in executive roles such as conducting inquiries and royal commissions.

The Supreme Court of New South Wales provides a salient example of this practice. Judges of this Court face compulsory retirement at age 72,[93] but a qualified person may be appointed as an acting judge of the Court beyond that age for a period not exceeding 12 months—for example, to fill a temporary judicial absence or ameliorate a court backlog.[94] The problem of mental decrepitude is dealt with by the short term nature of acting appointments and by setting additional age limits—age 75 or 77, depending on the circumstances. The problem of preserving judicial independence is addressed in part by the fixed term nature of the appointment; by the constitutional prohibition on removing an acting judge during the fixed term other than for proved misbehaviour or incapacity;[95] and by the setting of their remuneration by an independent tribunal. Yet, the ‘fragile bastion’[96] of judicial independence is not fully protected by these arrangements—there is no restriction on re-appointment, which opens the door to executive preferment, and there is no restriction on acting judges holding other offices or employment.

Although acting judges in the New South Wales Supreme Court are not required by law to be retired judges, the facility is widely used in this way. The Supreme Court’s 2012 annual report lists nine persons who held office as acting judges during that year, compared with 48 permanent judges.[97] Together, the acting judges contributed 816 days of judicial service to the Supreme Court in 2012. While one may question whether the regulatory regime sufficiently safeguards judicial independence, there is little doubt that it is well-utilised by the executive as a flexible tool for returning mandatory retirees to the bench. Yet it does so at some cost: acting judges are remunerated at a daily rate in addition to any pension they are entitled to receive as retired judges.

C. Tarrying Longer: Extending Service in South Africa

A third strategy for addressing problems of judicial tenure has been to relax the limitations inherent in the constitutional rules. This is evident in South Africa, where the original term limit of seven years for judges of the Constitutional Court was seen as too short, and in Australia, where the age limit of 70 years is now regarded by many as too young.[98]

The experience of the Constitutional Court has been set out above. The 1993 interim Constitution imposed a non-renewable term limit of seven years, which was increased in 1996 to 12 years under the final Constitution, and then made subject to further extension by legislation in 2001, as a result of which the maximum term now stands at 15 years in some circumstances. These changes reflect the growing confidence of the parliament, the executive and the public in an experimental institution that was, in its early years, fiercely independent yet politically astute in charting a new course in democratic constitutionalism.[99]

The tenure provision in s 176 of the South African Constitution has remained the subject of active debate, although it has not been altered again. In 2010, a draft constitutional amendment bill proposed that s 176 be amended to create a unified system of tenure for judges of superior courts in South Africa—the revival of a proposal that was made in 2001.[100] This proposal abandoned the idea of a non-renewable constitutional term of 12 years, providing instead that a Constitutional Court judge ‘holds office until he or she attains the age of 70 or until he or she is discharged from active service in terms of an Act of Parliament’.[101] However, the Act that passed through Parliament and is now in force did not contain this provision.[102]

6. Balancing Conflicting Values

The preceding discussion has shown that there are complex policy choices at stake in crafting arrangements for judicial tenure in modern constitutional democracies. This Part examines some of the central tensions in five dyadic relationships.

A. Independence and Accountability

A A Paterson pithily summarised the conflicting values in this area when discussing United Kingdom legislation that allows the Lord Chancellor to declare a judge’s office vacant if a judge becomes permanently infirm and is incapacitated from resigning:

‘On the one hand there is belief that in a democracy the rights of the citizens are best protected by some form of separation of powers and by the independence of the judiciary from external pressures or controls. On the other hand there is the democratic notion that public officials who are entrusted with power should be held accountable to the nation, and must be fit persons to exercise these powers.’[103]

Life limits, age limits and terms limits are different solutions to the problem of executive interference in the exercise of judicial functions, such as the English experienced during the reign of the Stuart Kings. Although external interference is not the only threat to be guarded against, this type of decisional independence has become a value of the highest order in assessing models of tenure. Life tenure provides the greatest bulwark against executive interference but the other models do not seriously compromise that goal so long as the age limit is not too young nor the term limit too short (requiring departing judges to seek post-judicial employment). In the case of term limits, it is also important that judicial terms are non-renewable so that judges have nothing to gain or lose by deciding cases for or against the government of the day.

Judges are very much alive to potential threats to their independence, as can be seen in the Justice Alliance Case, which concerned the tenure of the Chief Justice of the Constitutional Court.[104] The case ruled on the validity of s 8(a) of the Judges’ Remuneration and Conditions of Employment Act 2001 (South Africa), which provided that a Chief Justice who becomes eligible for discharge from active service may, at the request of the President of the Republic, continue to perform active service until 75 years of age. The section thus allowed the term of a Chief Justice (but no other judge) to be extended at the discretion of the executive. Thus it was that, in April 2011, President Zuma wrote to Chief Justice Ngcobo to request that he remain in office for an additional five years to provide leadership to the judicial branch during a period of critical transformation. The Chief Justice, who was then 58 years of age and had completed 11.8 years of service on the Court, acceded to the request but the events quickly led to a constitutional challenge. A unanimous Constitutional Court (absent the Chief Justice) struck down s 8(a). The Court held that s 176 of the Constitution gives the power to extend the terms of Constitutional Court judges to the Parliament, but that s 8(a) was an unlawful attempt to usurp that power by delegation to the executive. Such a delegation was impermissible because ‘non-renewability is the bedrock of security of tenure and a dyke against judicial favour in passing judgment’.[105] Moreover, the Act was invalid in so far as it sought to single out the Chief Justice from other judges of the Court in conferring a benefit by extending the term of office.[106] In the result, the Chief Justice withdrew his consent to serve for an additional period and ceased to hold office on the expiration of his 12-year term.

Weighed against the demands of judicial independence is the need for judicial accountability. The problem was posed during the United States ratification debates when Robert Yates, writing as Brutus in the Anti-Federalist Papers, proffered the vatic observation that life tenure would make judges ‘soon feel themselves independent of heaven itself’.[107] In the present context, the problem is at its starkest when a life tenure judge is incapable of discharging his or her duties by reason of mental decrepitude but nonetheless refuses to retire. The usual mechanisms of judicial accountability—conduct of proceedings in open court, delivery of reasons for judgment, and appellate review—would ordinarily expose such judges to adverse public scrutiny and might nudge them towards retirement. It has been suggested that the declining productivity of elderly judges has been masked in the United States in recent years by the increasing delegation of opinion writing to law clerks, which has allowed ‘a small number of senile judges’ and a larger number of senescent judges to continue in office well past their prime.[108] However, judicial ‘ghost-writing’ is not generally practised in Australia, or it seems South Africa, where judges write their own judgments.

B. Constancy and Change: The Composition of the Bench

A second tension in the models of judicial tenure is the balance between constancy and change in the composition of the bench. Joseph Raz has argued that stability is an important principle underpinning the rule of law because it allows people to know the law for the purpose of short-term decision making and long-term planning;[109] or, as C L Ten expresses it, laws should not be changed too frequently because otherwise they are ‘difficult to comply with and thereby fail to direct people’s conduct’.[110] While this derives from a ‘thin’ or ‘formal’ version of the rule of law which does not address the characteristics of a good system of laws or government, it is widely accepted as a minimum content of the rule of law.[111] It is a short step to conclude that stability in the composition of a court promotes stability in its jurisprudence, especially in appellate courts that have a clear law-making function. This is not to say that long-serving judges do not change their opinions over time, but seismic shifts in legal principles are less likely when the personnel interpreting and developing them are not subject to frequent change.

Pitted against the need for stability on the bench is the need for change to ensure that evolving social values are broadly reflected in decisions of the courts, especially when judges are called on to interpret and apply Bills of Rights. As a former High Court justice observed, the rules relating to tenure should provide for ‘regular and seemly exits’ so that the final court can be ‘dynamic and open-minded’.[112] The argument is not that judges should be a simulacrum of the people on whose behalf they interpret and apply the law but that frequent turnover ensures that judges are not too far out of kilter with the ethos of the community they serve. For courts at the highest level, the policy preferences of judges should be refreshed regularly for reasons of good governance and democratic legitimacy.

There is an important linkage between the model of tenure and diversity of the bench because tenure directly impacts the rate of judicial turnover. In the United Kingdom it has been observed that the pace of change in the judiciary has generally been slow because there is a limited number of judicial positions held until retirement, and entry into the profession can only be achieved incrementally, following the retirement of sitting judges.[113] For this reason a House of Lords Select Committee recommended differential retirement ages for judges at different levels of the hierarchy. This would promote diversity by ensuring that posts become available at the lower levels while leaving time for talented individuals who have not followed a traditional career path to reach the highest levels.[114] A short term of office can promote diversity on the bench by providing the executive with an opportunity to make fresh appointments that reflect the composition of society (e.g. by race or gender, as the South African Constitution requires).[115] Yet gains in diversity that are quickly won can also be easily lost, which was a potential danger when five new judges were appointed to the Constitutional Court in a single year in 2009.[116]

The goal of stability favours life limits or reasonably long term limits but in principle it says nothing about age limits because the length of service depends on the age at appointment. However, given the observed fact that the judges examined here are generally appointed in their early fifties, stability can also be achieved by age limits that are not too young. In contrast, the goals of change and renewal are best served by shorter term limits and younger age limits, and are the antithesis of life tenure which permits the development of a geriatric bench. Subject to the limitations of the South African data, these generalisations are supported by the statistics presented in Part 3, which show that the mean length of service on the Supreme Court has been 25 years or more for the past 20 years, while judges on the High Court and Constitutional Court have served for a decade less.

C. Cost and Effectiveness

A third but often unarticulated tension exists between the economic cost of different models of tenure and their effectiveness in achieving the objectives of the judicial system. The tension is encapsulated in the pressure faced by all modern judicial systems to produce outcomes that are just and cost-effective. The issue of effectiveness has been canvassed above—the critical question is whether the tenure model, which affects the age of judges and their length of service, adversely impacts on the adjudicatory process. It could do so if aged or long-serving judges are less able to resolve disputes in a timely manner, or produce decisions of lower quality, or are more prone to error. The latter situation imposes burdens on the parties and the legal system through the instigation of avoidable appeals (if they are available) or the failure to resolve disputes according to law, with a consequent erosion of the rule of law.

It is the economic cost of different tenure models that has gone most unremarked. The appointment of judges imposes direct costs to public finance through salaries, pensions, personal staff and facilities, and these costs vary from model to model. A lack of transparency sometimes arises because legislatures tend to bias the compensation of judges towards non-salary benefits such as pensions, which are harder to value and less likely to provoke public discontent.[117]

The balance between cost and effectiveness is illustrated by the remuneration of federal judges in Australia. During their years of active service, judges are paid a salary set by an independent tribunal. Once they have reached 60 years of age and completed 10 years’ service, they are entitled to an annual lifetime pension calculated at 60 per cent of the current salary of an equivalent judge. After their death, the judge’s spouse is then entitled to an annual lifetime pension calculated at 62.5 per cent of the judicial pension. The combined value of these pensions depends on the longevity of the judge and the spouse, but for a male judge who retires as soon as his pension vests—i.e. at 60 years after 10 years’ service, which is a reasonably common occurrence in federal courts other than the High Court—the expected real value of the pension component is 2.6 times larger than the total salary paid to the judge over his 10 years of service.[118]

Different tenure arrangements create complex trade-offs between different components of cost on the one hand (e.g. salary versus pensions), and between economic cost and effectiveness on the other. Increasing the age limit or re-introducing life tenure would encourage Australian judges to retire later than the current mandatory retirement laws require. Every extra year of judicial service requires the state to pay more in salary than it saves in pension (because the pension is 60 per cent of salary), but the marginal cost of that option is less than the cost of appointing a new judge to provide equivalent labour, since a new appointee generates no pension saving. On the other hand, each extra year of service increases the likelihood of falling productivity or rising decrepitude, which impacts on an ageing judge’s effectiveness. Although the trade-offs are unique to the retirement and remuneration arrangements in each jurisdiction, the general principle is well understood by executive government: longer serving judges save direct public expenditure but at the risk of diminishing effectiveness.

D. Rigidity and Flexibility: The Level of Regulation

A fourth tension is the respective roles of the constitution and legislation in regulating judicial tenure. Comparative practice suggests that constitutions need not contain every provision that affects judicial tenure but nor should they remain silent. The quest is to find an appropriate balance between rigidity and flexibility, since constitutions are purposefully difficult to amend, while legislation is subject to the transitory will of the majority of elected representatives. The tipping point will depend, among other things, on the ease with which the constitution can be amended in theory and practice.

The rules most suitable for constitutional inclusion are those that go to foundational architecture (such as the choice between alternative models of tenure) and those that seek to protect the judiciary from legislative or executive encroachment. Within a socially acceptable range, finer details can be left to statute-makers. For example, if term limits are the chosen architecture, the constitution should specify that terms are non-renewable, and stipulate a minimum term or a span of years within which the legislature may make choices. If age limits are the chosen architecture, the constitution should specify a minimum age for appointment and a maximum age for retirement, subject to legislative extension. In either case, the constitution should articulate enduring principles that protect judicial independence. These include the principles that the legislature cannot alter (or at a minimum, cannot reduce) the term of a judge who has already been appointed, and that age limits and term limits should apply to all judges of a particular class and not be individuated.

The Australian and South African experience show that constitutions falter when they over-specify and thus entrench policy choices that are impervious to changing social circumstances. When the age limit for federal judges was adopted in Australia in 1977, male life expectancy at birth was 69.8 years; almost identical to the age limit of 70 years. By 2009, when the Senate recommended increasing the age limit to 72 or 75 years, male life expectancy had risen to 79.5 years; 14 per cent higher than the mandatory retirement age. How relevant will the constitution be in 2061, when male life expectancy is projected to reach 92.1 years; 32 per cent higher than the current age limit?

E. The High and the Low: Differentiating between Courts

A final tension is whether the same tenure model should apply to all courts within a country or whether justifiable distinctions can be drawn between courts based on their position in the court hierarchy or the subject matter of their jurisdiction. This article has focussed on judicial tenure in three pre-eminent appellate courts but tenure arrangements are not uniform within those countries. Consider South Africa. For judges of the Constitutional Court, the Constitution currently stipulates a hybrid model comprising term limits (12 years) and age limits (70 years) subject to legislative extension; yet for judges of other courts, the Constitution leaves both the choice of model and its details entirely to the legislature.[119] In fact, the Parliament has chosen to impose an age limit (70 years) for non-Constitutional Court judges, although that limit is relaxed if a judge would reach 70 before serving for 10 years.[120]