|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

UNSW Law Society Court of Conscience |

Niamh Kinchin*

In 2020, the United Kingdom (‘UK’) abandoned an algorithm that was used to stream immigration applicants. Applications were triaged using a ‘traffic light’ colour code system (i.e. red, green, amber) according to the category of risk. Advocacy groups, such as the Joint Council for the Welfare of Immigrants and FoxGlove, claimed the algorithm was discriminatory by design,[1] and violated the UK Equality Act 2010,[2] because some nationalities were categorised as ‘suspect’ based on higher rejection rates. Consequently, applicants from those countries received a higher risk score and a higher level of scrutiny. Previous visa rejections were fed back to the algorithm to inform future decisions, reinforcing bias and discrimination and causing a feedback loop.

Algorithmic risk assessments continue to be used for visa processing and immigration detention worldwide, including in Australia. Notwithstanding their potential to impact fundamental human rights, including liberty and humane treatment, risk assessment tools tend to become more punitive over time, creating harmful feedback loops and avoiding the oversight of courts. Risk-based regulation of emerging technologies that include private providers of government services accompanied by meaningful reform of the scope of judicial review will be essential to addressing the rise of potentially harmful technology in Australian immigration and border control.

I The Rise Of Algorithmic Risk Assessments

Australia has used algorithmic risk assessments inside its immigration detention centres for several years.[3] The Security Risk Assessment Tool (‘SRAT’), developed by the global corporation Serco, gives each detainee a security risk rating to determine whether a person is at low, medium, high, or extreme risk for escape or violence. The risk is calculated based on the detainee’s pre-detention behaviours and incidents during detention, such as abusive or aggressive behaviour, assault, possession of contraband or the refusal of food or fluids. A detainee’s risk score may determine their treatment during transportation, including whether they are placed in handcuffs or a spit hood, which detention centre or compound within the centre they are placed in, whether they are held in a cell while at court awaiting a hearing and whether their case is referred to the Minister to consider less restrictive alternatives to immigration detention.

The United States Immigration and Customs Enforcement (‘ICE’) has used a risk assessment tool called Correctional Offender Management Profiling for Alternative Sanctions (‘COMPAS’) since 2013. Database records and interview information are combined to produce a weighted scoring system that categorises security and flight assessments as low, medium, and high risk. Based on this information, COMPAS determines whether immigrants will be detained with no bond, detained with bond eligibility or released under community supervision. Other examples of algorithmic risk assessments for immigration include a since-abandoned profiling tool used in New Zealand to flag potential ‘troublemakers’ by analysing the historical data of ‘illegal immigrants’ for denial of entry or deportation.[4] Similarly, Canada’s Chinook system flags immigration applications as high or low risk based on specific risk indicators, which are referred to an officer to assist in decision-making.[5]

II Punitive Creep And Feedback Loops

Algorithms that assess risk rely on data that identifies particular risk factors. However, the data that feeds the algorithm – and the model itself – can be compromised by bias. Historical bias emerges when the process of creating data is tainted by social inequities, which are often rooted in discrimination based on race and other protected characteristics.[6] User interaction bias, which is when the user self-selects biased behaviour and interactions,[7] can cause the model to learn from and reinforce that behaviour. Data and user-interaction bias create a significant risk for algorithmic assessments relating to detention, creating harmful feedback loops and encouraging the algorithm to evolve in a punitive way.

Algorithmic risk assessment tools have historically been used most widely – and controversially – in policing. ‘Predictive policing’ has been described as:

The use of dynamic prediction models that apply spatio-temporal algorithms... with the purpose of forecasting areas and times of increased crime risk, which could be targeted by law enforcement agencies with associated prevention strategies designed to mitigate those risks.[8]

Whilst firmly part of US policing practice for several years,[9] predictive policing has limited application in Australia and is mainly used in child exploitation, family and domestic violence and police misconduct operations.[10] Predictive policing that identifies risky ‘crime hotspots’ has been criticised for causing discriminatory feedback loops. Police are more likely to make arrests in areas with a strong existing police presence. As a result, using arrest data to predict crime hotspots tends to focus policing efforts disproportionately on communities that are already heavily policed.[11]

Algorithmic risk assessments for immigration detention and deportation can also generate feedback loops because they tend to become more punitive over time. In the US, researchers found that COMPAS gradually recommended release or bond for fewer and fewer categories because ICE officers increasingly overrode the COMPAS algorithm when it recommended non-detention.[12] Subsequent adjustments to the algorithm took into account the rate of ICE officer dissent as a core metric, conforming to officers’ more punitive detention preferences and acting as a feedback loop that informed subsequent updates to the system.

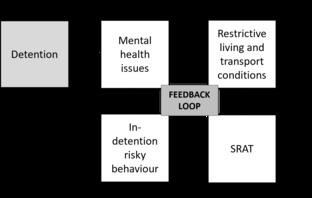

The Australian SRAT is at equal risk of evolving punitively for different reasons. Risk ratings are partly based on behaviour inside detention. It is widely accepted that detention causes mental health issues,[13] and those issues, including the use of force by officers in detainee ‘behaviour management’,[14] can contribute to resistant, risky and often self-harming behaviour.[15] Risky behaviour informs the SRAT, which will declare a person high risk and recommend restrictions on their living conditions and movements. Heightened living and transport restrictions are likely to exacerbate risky behaviour, causing a feedback loop.

Figure 1: SRAT Feedback Loop

Migration is commonly associated with risk in political, policy and popular discourse.[16] Marginalised groups, often categorised as ‘illegal immigrants’, are perceived to pose risks to the mainstream community, embodying fears not only about risk but also the potential breakdown of social order and the necessity to uphold social boundaries and divisions.[17] Ulrich Beck warns that the perception that risk is inherent in modern society gives rise to ‘risk science’, which generates ‘risk tools’ that may produce new risks, such as public scepticism.[18] Although Beck’s work relates to modernity and technological change, a central premise can be applied here: risk can beget risk. Human response to algorithmic risk assessments (i.e., ‘risk tools’), whether by officers or detainees, solidifies and increases risk-based consequences.

III SRATs: Beyond Judicial Scrutiny?

Internationally, judicial scrutiny of algorithmic risk assessment tools is uneven and has primarily been limited to human rights adjudication. In February 2020, for example, the District Court of the Hague ruled that the use of the SyRI algorithm system (‘System Risk Indication’), a digital welfare fraud detection system applied by the Dutch Government, violated Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights,[19] which creates a right to respect for private and family life. In the 2018 Canadian case of Ewert v Canada, the court found that ‘psychological and actuarial risk assessment tools’ used to determine the risk of recidivism were in breach of s 7 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, which guarantees the right to life, liberty and security of the person.[20]

Despite the detrimental impact that algorithmic risk assessments like SRAT and COMPAS can have on the liberty and humane treatment of immigration detainees, they can avoid the scrutiny of courts. In the US case of State v Loomis,[21] the Wisconsin Supreme Court held that using COMPAS in sentencing did not violate the defendant’s constitutional due process rights despite its assessment methodology being kept from the court and defendant. Although Loomis had an opportunity to ‘refute, supplement, and explain’ the COMPAS risk assessment score, he had no way of knowing how it was calculated.

In Australia, it could be that scrutiny of SRATs may occur as part of the review of administrative decisions subject to judicial or merits review. S 501(6)(aa) of the Migration Act 1958 (Cth) states that one of the reasons a visa can be refused or cancelled on character grounds is if a person committed an offence during or after an escape attempt. It may be that the SRAT assessment contributed to that offence in the sense of the feedback loop discussed above. Although not impossible, persuading the Administrative Review Tribunal[22] to set aside a visa refusal decision based on the material contribution of a faulty SRAT assessment would be difficult.

Judicial review would undoubtedly prove challenging. The High Court’s failure to extend judicial review to private bodies exercising ‘public power’ to Australia[23] in line with the UK case of Datafin[24] means that Serco’s private nature places its decisions outside the court’s scrutiny and, critically, the demands of procedural fairness. The court has ‘left to another day’ the question of whether jurisdiction for judicial review under s 75(v) of the Constitution and s 39(B) of the Judiciary Act 1903 can apply to private contractors.[25] Being a product of the contract between the government and Serco, SRAT assessments are not made under legislation and, therefore, not reviewable under the Administrative Decisions (Judicial Review) Act 1977.[26] Further, an argument, for instance, that an SRAT assessment was a matter that materially affected the decision by depriving a person of the possibility of a successful outcome[27] or that a decision that considered SRAT (amongst other things) was ‘unreasonable’ because it lacked evident and intelligible justification[28] would be a long bow to draw. The obstacles to an outcome that deems SRAT assessments unlawful are indeed high.

I Law Reform

A March 2024 article about SRATs by The Guardian reported that detainees were not aware of the tools or their own assessment scores.[29] This lack of transparency and judicial scrutiny, combined with the recognised high-risk nature of algorithmic risk assessments in migration and asylum,[30] calls for a multidimensional approach to law reform.

Australia does not yet have artificial intelligence (AI)–specific regulation, but in January 2024, the government released its interim response to the ‘2023 Safe and Responsible AI consultation’, which detailed its intended approach to AI regulation.[31] The response included a commitment to use ‘a risk-based framework to support the safe use of AI and prevent harms occurring from AI’. On 5 September 2024, the Department of Science, Industry and Resources released a proposal paper introducing mandatory AI guardrails in high-risk settings.[32] Whilst a promising start, three words of caution are warranted. First, SRATs could avoid full transparency measures if excluded from regulation based on their ‘public order’ nature. The EU’s Artificial Intelligence Act (‘AI Act’), which models a risk approach to AI, requires registration in a public database for high-risk systems but excludes systems used in law enforcement and asylum and border control management.[33] Instead, these systems must be registered in a ‘secure non-public section of the EU database’. Second, regulation must extend to private organisations providing essential public services if providers like Serco are to fall within its scope. Third, human rights are integral to AI regulation.[34] The EU AI Act requires high-risk systems to be accompanied by human rights impact assessments before being deployed in the market. The ability of human rights impact assessments to bring international human rights, such as privacy rights, into the domestic context is particularly important for Australia, which does not have an explicit human rights-based constitutional framework on which the courts can rely.[35] Perhaps this is another good reason for a federal Human Rights Act.

Beyond developing effective AI regulation that addresses gaps such as a provider’s private nature and unhelpful transparency exclusions ex-ante, fundamental reform is needed to the scope of judicial review. In acknowledging the changing way public services are delivered in the modern state, the focus must shift from the public or private nature of the decision-maker’s identity to its functions.[36] In short, Datafin should be extended to judicial review in Australia. Indeed, as Bleby argues, if we are to avoid Kirk’s ‘islands of power immune from supervision and restraint’[37] and recognise the rise of pluralist democracy and corporatism, it is inevitable.[38] If judicial review were to be applied to private bodies carrying out governmental but non-statutory functions, such was the case in Datafin, the SRAT assessments may be considered integral to the government’s regulatory approach to migration management and border control, allowing for full judicial scrutiny.

Public oversight bodies and private law remedies can contribute to the mitigation of harm to individuals impacted by SRATs. The Commonwealth Ombudsman, in its oversight role of migration detention, has expressed concerns that the tool does not account for ‘established sociological and psychological assessments of violent behaviours, or the likelihood of reoffending’.[39] A continued focus on SRATs by the Ombudsman will ensure they remain illuminated to the public. The Human Rights Commission is an important voice for migration detainees, highlighting the impact of risk assessments on individuals[40] and providing commentary on the tool’s ethicality and functionality.[41] Torts and duty of care are increasingly becoming a pathway for redress for harm in detention,[42] attested by recent settlements in relation to the medical treatment of children detained in Nauru.[43] If SRATs are to be defined by harm, they may become a part of that conversation. However, robust regulation and administrative review will have the greatest impact in securing broad-scale, systemic accountability for the implementation of harmful technologies.

VI Conclusion

Algorithmic risk assessments can label immigrants as security risks, affecting their detention, treatment and liberty. There are no doubt efficiency and safety benefits, but their propensity to become more punitive over time and create harmful feedback loops raises hard questions about the place of judicial and legislative scrutiny. In Australia, a lack of judicial review means a denial of procedural fairness and, consequently, the kind of robust oversight required when the most fundamental human rights are involved. Law reform in this area will have a broad impact beyond algorithmic risk assessments. In ensuring that private providers of government services are accountable through regulatory measures and judicial review, Australia could make strides towards embracing and responding to the pluralist democracy it has become.

* Dr Niamh Kinchin is an Associate Professor at the Faculty of Business and Law in the University of Wollongong.

1 ‘Home Office Drops ‘racist’ Algorithm from Visa Decisions’, BBC (online, 4 August 2020) <https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-53650758>.

[2] Equality Act 2010 (UK) ss 9, 13, 19.

[3] Ariel Bogle, ‘Revealed: the Secret Algorithm that Controls the Lives of Serco’s Immigration Detainees’, The Guardian (online, 13 March 2024) <https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/ng-interactive/2024/mar/13/serco-australia-immigration-detention-network-srat-tool-risk-rating-ntwnfb-?CMP=Share_AndroidApp_Other >; Commonwealth Ombudsman (Cth), Immigration Detention Oversight: Review of the Ombudsman’s Activities in Overseeing Immigration Detention January to June 2019 (Report No 1, February 2020) (‘Ombudsman Report Jan-June 19’) .

[4] Lucia Nalbandian, ‘An Eye for an “I”: A Critical Assessment of Artificial Intelligence Tools in Migration and Asylum Management’ (2002) 10(32) Comparative Migration Studies 10, 9–13.

[5] Reza Aslami, ‘Chinook Canada – IRCC Decision-Making System’, Arnika Visa Solutions (Web Page) <https://arnikavisa.com/all-we-know-about-chinook-system/>.

[6] Ninareh Mehrabi et al, ‘A Survey on Bias and Fairness in Machine Learning’ (2021) 54(6) ACM Computing Surveys 115; Harini Suresh and John Guttag, ‘A Framework for Understanding Sources of Harm throughout the Machine Learning Life Cycle’ (Working Paper No 17, Cornell University Library, 4 November 2021).

[7] Mehrabi et al (n 6) 117.

[8] Daniel Birks, Michael Townsley and Timothy Hart, ‘Predictive Policing in an Australian Context: Assessing Viability and Utility’(Research Report No 666, Trends and Issues in Crime and Criminal Justice, Australian Institute of Criminology, 9 March 2023) 2.

[9] Sarah Brayne, Predict and Surveil: Data, Discretion, and the Future of Policing (Oxford Academic, 2020).

[10] Rick Sarre and Ben Living, ‘Artificial Intelligence and the Administration of Criminal Justice: Predictive Policing and Predictive Justice. Australia Report’ (2023) e-Revue Internationale de Droit Pénal 3.

[11] See generally Danielle Ensign et al, ‘Runaway Feedback Loops in Predictive Policing’ (2018) 81 Proceedings of the 1st Conference on Fairness, Accountability and Transparency 160, 160–71.

[12] Robert Koulish and Ernesto Calvo, ‘The Human Factor: Algorithms, Dissenters, and Detention in Immigration Enforcement’ (2021) 102(4) Social Science Quarterly 1761.

[13] Martha Von Werthern et al, ‘The Impact of Immigration Detention on Mental Health: A Systematic Review’ (2018) 18(1) BMC Psychiatry 1; Janet Cleveland et al, ‘Symbolic Violence and Disempowerment as Factors in the Adverse Impact of Immigration Detention on Adult Asylum Seekers’ Mental Health’ (2018) 63(8) International Journal of Public Health 1001; Derrick Silove, Patricia Austin and Zachary Steel, ‘No Refuge from Terror: The Impact of Detention on the Mental Health of Trauma-affected Refugees Seeking Asylum in Australia’ (2007) 44(3) Transcultural Psychiatry 359.

[14] Ombudsman Report Jan-June 19 (n 3) 19–22.

[15] Melissa Bull et al, ‘Sickness in the System of Long-term Immigration Detention’ (2013) 26(1) Journal of Refugee Studies 47; Alessandro Spena, ‘Resisting Immigration Detention’ (2016) 18(2) European Journal of Migration and Law 201.

[16] Allan M Williams and Vladimir Baláž, ‘Migration, Risk, and Uncertainty: Theoretical Perspectives’ (2012) 18(2) Population, Space and Place 167.

[17] Mary Douglas, Risk and Blame: Essays in Cultural Theory (Routledge, 1992) 7.

[18] Ulrich Beck, Risk Society: Towards a New Modernity (Sage, 1992).

[19] Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms, opened for signature 4 November 1950, 213 UNTS 222 (entered into force 3 September 1953); NJCM v the Netherlands (‘SyRI’) (District Court of The Hague 5 February 2020).

[20] Ewert v Canada (Correctional Service) (Judgment) [2018] 2 SCR 165.

[21] State v Loomis 881 NW 2d 749 (Wis, 2016).

[22] Visa refusals or cancellation decisions on character grounds by delegates of Ministers, but not Ministers personally, under Migration Act 1958 (Cth) s 501 are reviewable by the Administrative Appeals Tribunal (to be replaced by the Administrative Review Tribunal).

[23] In Neat Domestic Trading Pty Ltd v AWB Ltd [2003] HCA 35 [51] (McHugh, Hayne and Callinan JJ), the High Court found that it was not possible to impose public law obligations on a private body (AWB) while at the same time accommodating its private interests.

[24] R v Panel on Take-Overs and Mergers; Exparte Datafin [1986] EWCA Civ 8; [1987] 1 QB 815. The Court found that judicial review applies to private bodies carrying out governmental but non-statutory functions. Governmental functions were characterised by ‘public power’ integral to the government’s regulatory approach.

[25] Plaintiff M61/2010E v Commonwealth [2010] HCA 41; (2010) 243 CLR 319, 345 (French CJ, Gummow, Hayne, Crennan, Keifel and Bell JJ).

[26] Administrative Decisions (Judicial Review) Act 1977 (Cth) s 3 requires reviewable decisions to be ‘made under an enactment’.

[27] Applicant S270/2019 v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection [2020] HCA 32; (2020) 383 ALR 194.

[28] Minister for Immigration and Citizenship v Li [2012] HCA 61; (2013) 249 CLR 332, 76 (Hayne, Kiefel and Bell JJ).

[29] Bogle (n 3).

[30] The European Artificial Intelligence Act (2024) (European Union) (‘Artificial Intelligence Act’) classifies ‘migration, asylum and border control management’ as high risk in certain circumstances, including tools used to ‘assess a risk, including a security risk, a risk of irregular migration, or a health risk, posed by a natural person who intends to enter or who has entered into the territory of a Member State.’

[31] Department of Industry, Science and Resources (Cth), ‘The Australian Government’s Interim Response to Safe and Responsible AI Consultation’ (Media Release, 17 January 2024)

<https://www.industry.gov.au/news/australian-governments-interim-response-safe-and-responsible-ai-consultation>.

[32] ‘Safe and responsible AI in Australia: Proposals Paper for Introducing Mandatory Guardrails for AI in High-risk Settings’, Department of Industry, Science and Resources (Cth) (Web Page, 5 September 2024) <https://consult.industry.gov.au/ai-mandatory-guardrails>.

[33] Artificial Intelligence Act (n 30) art 49.

[34] Volker Türk, ‘What Should the Limits e? – A Human-Rights Perspective on What’s Next For Artificial Intelligence and New and Emerging Technologies’ (Media Release, Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, 12 July 2023). See also Australian Human Rights Commission, Submission to the Department of Industry, Sciences and Resources, Supporting Responsible AI (26 July 2023).

[35] Yee-Fui Ng et al, ‘Revitalising Public Law in a Technological Era: Rights, Transparency and Administrative Justice’ [2020] UNSWLawJl 37; (2020) 43(3) The University of New South Wales Law Journal 1041, 1045.

[36] Mark Aronson, Michael Groves and Greg Weeks, Judicial Review of Administrative Action and Government Liability (Lawbook Co, 6th ed, 2001) 142 [3.190].

[37] Kirk v Industrial Court of New South Wales (2010) 239 CLR 531, 581 [99] (French CJ, Gummow, Hayne, Crennan, Kiefel and Bell JJ).

[38] Chris Bleby, ‘Datafin: Endgame’ (2022) 104 Australian Institute of Administrative Law Forum 20, 30–5.

[39] Ombudsman Report Jan-June 19 (n 3) 17 [5.37].

[40] Australian Human Rights Commission, Mr RG v Commonwealth of Australia (Department of Home Affairs) (Report No. 148, 7 September 2023). At [9], see recommendation 3 – ‘The Department should require Serco to review the Security Risk Assessment Tool to ensure that it clearly identifies detainees who are vulnerable to harm from other detainees, and detainees who present a risk to the safety of other detainees’.

[41] Australian Human Rights Commission, Use of Force in Immigration Detention (Report No 130, 23 October 2019). At [105] the Commissioner says, ‘the quality of the ultimate risk rating calculated by the tool is reliant on the quality of information entered into it. For example, some incident types may capture a broad range of conduct of different degrees of seriousness, but are treated in the same way for the purpose of the tool. I am concerned that a commonly used category is “abusive/aggressive behaviour”, which encompasses both the use of bad language and conduct that is physically aggressive (but that does not amount to an assault)’.

[42] See Plaintiff S99/2016 v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection and Another [2016] FCA 483; (2016) 243 FCR 17.

[43] FBV18 v Commonwealth of Australia [2024] FCA 947; AYX18 v Minister for Home Affairs [2024] FCA 974.

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/UNSWLawSocCConsc/2024/18.html