University of New South Wales Faculty of Law Research Series

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

University of New South Wales Faculty of Law Research Series |

|

Last Updated: 4 October 2009

Beyond Methods - Law & Society in Action

Patrick Schmidt, Macalester College

Simon Halliday, University of

Strathclyde, University of New South Wales

Citation

This article is the introductory chapter of a book (Halliday, S. and Schmidt, P., Conducting Law and Society Research: Reflections on Methods and Practices, New York: Cambridge University Press, 2009).

Abstract

This essay is the introductory chapter of a book about research methods in the field of law and society (Halliday, S. and Schmidt, P., Conducting Law and Society Research: Reflections on Methods and Practices, New York: Cambridge University Press, 2009). Through interviews with many of the most noteworthy authors of law and society, Conducting Law and Society Research takes readers behind the scenes of empirical scholarship, showing the messy reality of the research process. The challenges and the uncertainties, so often missing from research methods textbooks, are revealed in candid detail. The accessible and revealing conversations about the lived reality of classic projects will be a source of encouragement and inspiration to those embarking on empirical research, ranging across the full array of disciplines that contribute to law and society. In this introductory essay, we argue for greater candor in discussing the messiness of empirical research methods, particularly in the field of law and society which has for many years explored the gap between rules and reality. We also examine the role which luck (both good and bad) plays in empirical research. Ultimately, we suggest that narratives of the research process such as the conversations contained in the book are a necessary complement to research methods textbooks. They reveal, in powerful ways, that “good research” displays not an absence of problems but the care taken in negotiating them.

Keywords: research methods; law and society; empirical research.

Introduction

One might be forgiven for wondering what is to be

gained from another book on research methods. There is certainly no shortage of

research methods texts, especially when one includes in the counting the volumes

written for the separate disciplinary traditions

that comprise Law and Society.

Yet for scholars about to conduct empirical work for the first time, or about to

attempt a very different

approach, there is more to be said about the social

realities of conducting research than is found in most of these texts. A proper

grasp of the philosophical underpinnings of various research methods, and an

adequate understanding of the practical prescriptions

about the mechanics of

research are clearly essential aspects of one’s training. However, the art

of cooking is more than the

following of recipes. Just as reading recipes in a

cookbook does not sufficiently prepare you for your first foray into the kitchen

(and certainly does not make you a good cook), most research methods books can

only take you so far in preparing you for fieldwork.

Orthodox methodological

texts have two important limitations in this respect.

First, they do not

generally convey a sense of what it feels like to be out in the field,

particularly when things go wrong or become difficult (which is almost always

the case). As the interviews

contained in this book suggest, research projects

are usually longer and their narratives more complex than the researcher would

have imagined at the outset. Although this has to be experienced firsthand to be

fully appreciated, the retrospective tales told

in this volume work particularly

well as a window onto the lived reality of research. They demonstrate powerfully

that one of the

major skill sets required of a fieldworker is not so much the

preparation of the project, though this is very important, but the

ability to

respond to the unexpected, to serendipitous opportunities and, almost

inevitably, to a certain level of disappointment.

It is a rare research methods

textbook that prepares students for the emotional dimensions of research and

academia and helps them

set expectations about what constitutes

“success” in research and publication.

Second, research methods

texts, and the presentation of research findings more generally, often remain

quiet about the imperfect path

of the research process. Although transparency

about research design and data collection is a basic principle of good social

science,

it takes a brave soul to give a genuinely “warts and all”

account of the mistakes that are made along the way, or of

other infelicities in

the research process. There is much to inhibit us from such complete candor.

Having made mistakes or missed

opportunities, scholars learn to paper over those

problems with a dispassionate voice and a cool recollection of the

methodological

steps. The “whole truth” of how research work

actually gets done tends to remain unspoken except perhaps to one’s

students, who hear these tales as reassurance when their own projects are mired

in ambiguity and struggle. It is difficult, in research

as in any area of life,

to share one’s insecurities.

Yet, particularly for Law and Society

scholars, there is surely both credit to be taken and comfort to be given in

being a little

more candid. We might usefully think about research methods as

embodying the “laws” of the research process. Prescriptions

about

the mechanics of data collection and analysis are, in important ways, the rules

and regulations of the social sciences—a

self-regulatory system controlled

through a mix of community and competition. And just as early socio-legal

scholars exposed the

gap between law in the books and law in action, so we

might, as a scholarly community, consider the gap which inevitably exists

between

research methods and the realities of research. Although normatively

important, we should not expect the prescriptions of research

methods found in

the textbooks to be perfectly mirrored in the research process.

Methodological Anxiety Syndrome

Responding to these limitations is more than an

intellectual exercise. They have a practical impact on researchers, particularly

those

new to the enterprise. Many students and scholars experience what we would

dub “MAS,” or Methodological Anxiety Syndrome.

MAS is a pervasive

and sometimes debilitating doubt about whether one has the necessary

methodological skills to embark on empirical

socio-legal work in the first

place. It is important to recognize that not all the disciplines which

contribute to the Law and Society

field engage in the same kind of

methodological training. In particular, those coming from law schools may have

received no training

whatsoever in social science research methods. Yet,

socio-legal research has a particular appeal for lawyers who have become

frustrated

and/or bored with the limits of doctrinal scholarship, as a number of

the contributors to this book can testify (see, for example,

chapter 5 with

Lawrence Friedman, chapter 8 with David Engel, chapter 9 with Keith Hawkins, and

chapter 15 with Gerald

Rosenberg.)[1] It is

easy, we suggest, for legal scholars asking socio-legal questions to be

intimidated by the apparent mystery of research methods,

and to be held back

from conducting empirical work because of their lack of formal training.

Piercing criticism from social scientists

of scholarship by

lawyers—attacked as insufficiently attentive to the “rules” of

empirical research methodology—can

all too easily be read as only

discouraging exploration or raising barriers to participation in the

interdisciplinary

dialogue.[2]

However, as a number of the chapters in this book demonstrate, formal

training, although invaluable, is not always a pre-requisite

to the conduct of

high quality socio-legal research (see, for example, chapter 2 with Stewart

Macaulay, chapter 7 with Alan Paterson,

and chapter 16 with Michael McCann). We

do not suggest that training in research methods is unimportant – far from

it. There

is no immunity from the obligation to be as complete and transparent

as possible in describing one’s steps in empirical research,

and training

can provide both the vocabulary and imagination necessary for conceptualizing

and communicating good scholarship. Yet,

we suggest that an awareness of

methodological issues and the requisite sensitivity to methodological questions

can still be gained

where formal training has not been available. In the world

of computer programming, software developers openly speak of the

“naïve

implementation” of a solution - the first, simplest, and

often “textbook” way to get a piece of software up and

running. But

they cannot end there, if they are to be successful. Software may even be

released to the public in “Beta”

form, with many problems yet to be

identified and new versions to be released. Law and Society research typically

proceeds on a similar

basis: beginning with a naïve design, but informed

and evolved through experiences in the field and engagement with the data.

Only,

we have not done so well at naming and accepting the importance of

“naïve fieldwork” in the research process.

In this

understanding, then, being methodologically thoughtful—that is,

possessing the capacity to move from the naïve understanding of one’s

project to the more sophisticated,

and to discover the questions, theoretical

potential, and epistemological problems latent in your engagement with the world

as you

see it—is ultimately much more important that being

methodologically trained. Some of the interviews in this volume should

give

considerable encouragement in this regard, as examples of how to enter the field

even when formal training is lacking, while

developing one’s capacity for

empirical research in the process.

MAS, of course, is not restricted to those

without formal methods training. It also refers to debilitating doubts about the

extent

to which one’s research projects has met the methodological

standards of the field and so may constitute acceptable scholarship.

Many

scholars, us included, know the feeling of things having “gone

wrong” or having realized well after the fact that

a step taken was less

than ideal, or worse. Such doubts about methods holds some people back from

seeking publication in the best

journals of the field. The sentiment that

“this can’t possibly be good enough to publish in the Law and

Society Review” is a self-fulfilling prophecy when one never submits

it. Since we began this project, many people have told us of graduate

students—those in different careers today—who went out into the

field, sometimes to foreign countries, to begin their

research. Finding

“the real world” so different from their theoretical expectations

and the approach they had designed

for it, they became frustrated, lost in the

ambiguity, and never completed their degrees.

Most forbidding of all, doubt

and anxiety generate a collective silence that no one person can break. We

suggest that research methods

need to be demystified and understood as social

practices, just as surely as socio-legal scholars believe that law’s claim

to autonomy and superiority must be laid bare. The collection of interviews in

this volume makes an important step towards that goal.

Serendipity and Bad Fortune

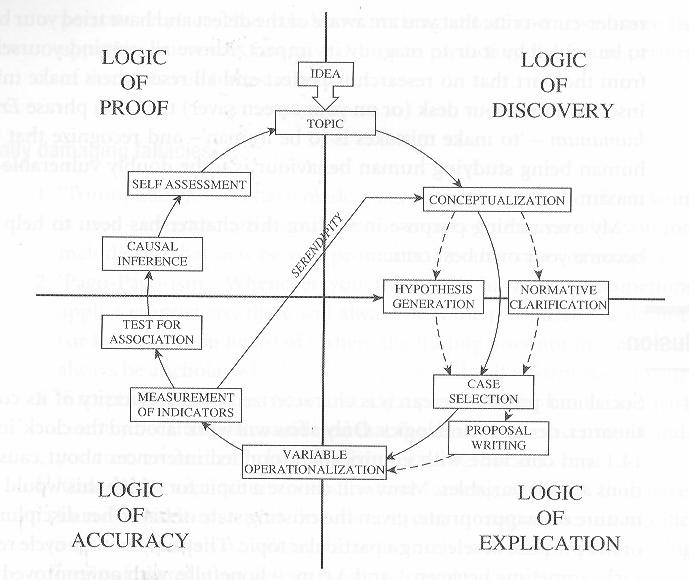

W. H. Auden suggested that “a poet will always have a sneaking regard for luck because he knows the role which it plays in poetic composition.”[3] Before embarking on this project we sensed that, just as in the arts, serendipity played a significant role in the production of social science. Of course, others have pointed to serendipity. Consider an example from a recent, excellent collection of methodological essays (see Figure 1).[4]

Figure 1: Serendipity in Methodology – One Formulation

Source: Schmitter (2008), Figure 14.3.

Amid the grand unified theory represented in the figure, incorporating all of

the logics of enquiry and analysis, a thin line labeled

“serendipity” cuts across and intervenes. It seems out of place, a

sharp juxtaposition between the concreteness of the

process and the “black

box” that happens at some point in good research. But how can this

mysterious dimension be explored

and communicated to others? Is serendipity more

than insight, or even genius that cannot be acquired, only possessed?

Serendipitous

experiences may be too idiosyncratic and context-dependent to

articulate in a systematic way, but that is not to say we shouldn’t

attempt an investigation into the craft that occurs at this level of

specificity.

Of course, amid the chance developments and insightful

realizations that help to refine a research project, the research process throws

up bad fortune as well as good. Our second instinctive hypothesis was that

ambiguity and difficulty were the rule rather than the

exception in empirical

research. We suspected that behind most research projects—right up to the

most insightful socio-legal

projects, the ones we teach and turn to for our own

inspiration—were stories that would settle the nerves of every aspiring

researcher. By reaching out to leading scholars in the field, and asking for

their reflections on their projects, we appreciated

that we were putting people

into an academic confessional. We knew we would hear of challenges and how many

of these hurdles were

overcome (or else these works would not exist as well-read

and much-discussed contributions to the field), but we would also draw

attention

to mistakes and the limitations of these studies. Our approach is not to meet

candor with criticism. While there are unquestionably

norms and best practices

for research methods, analysis, and interpretation, we maintain a less normative

stance, one that views

ambiguity and difficulty as essential elements of

the research process. For research to be at the cutting-edge, the researcher

needs to be discovering new areas of study,

finding new communities or subjects

of research, or testing new analytical frames. The ambition to discover

something new about the

world brings the research into engagement with the

world. A judge may believe that his or her task is to find the most closely

matched

precedent to answer the case at hand (however discretionary we know that

task to be); a researcher who is not simply replicating

existing research does

not have that comfort. Every research project is, in some way, a project of

“first impression”,

a de novo attempt to find the world

through a new slice or with a new lens. Uncertainty and doubt will be the

researcher’s faithful companion.

This collection of interviews, if it

adequately captures the way research methodology works “in action”,

does not free

anyone of the need to be thoughtful, intentional, and reflective

about methods. What it might do, however, is relieve many of the

worries that

plague students and scholars.

Law and Society in the Confident Age

Though not a guiding purpose of this volume, in the

course of conducting the interviews we came to appreciate the collection as

having

a secondary value, functioning as an oral history, of sorts, of well

known and well regarded Law and Society research projects. Law

and Society as an

academic field and an organization are now firmly established, and the findings

of affiliated scholars have found

their way into curricula and policymaking

around the globe. Yet, fortunately, the field is young enough that many of its

founders

are around to tell their tales. The organizational history of Law and

Society has been told in other

places.[5] Also, the

stories of many research projects, including some of those in this book, have

been re-told at conference panels or lectures

to students, and occasionally

published as individual pieces. Still, while our primary emphasis has been on

understanding how projects

took shape and overcame challenges, we have

appreciated our position of hearing these stories and believe that others will

too. Both

for those with long-standing familiarity with the projects in this

volume, and for those coming to these analyses anew, there is

an intrinsic

interest in hearing the research stories which underpin them, one that requires

no justification.

Of course, there are many limitations to this volume if

approached as history. Having focused on the social realities of research,

our

dialogues with authors leave unexplored—or edited out due to limitations

of space—many features an historian might

think to ask or include. Perhaps

more significantly, the interviewees, while representing a diverse group of

scholars and projects,

were not sampled with a broader historical record in

mind. Having initially toyed with the notion of constructing a collection of

the

“classic” works in the field, we quickly retreated from that frame

for somewhat obvious good reasons. To attempt

to capture a group of studies

which represented “the classics” would be an almost impossible task

and necessitate a controversial

claim, especially in a field as diverse as Law

and Society.[6] Further,

it would have restricted our focus to the earlier period of the Law and Society

movement. This would have undermined our

primary goal of creating a useful

resource for junior researchers of various intellectual interests and

methodological approaches.

In our collaborative discussions about the plan of

the book, we frequently pointed to more recent works that we thought presented

wonderful models of field research but that may not yet have attained the iconic

status possessed by older works. We also wanted

to focus on projects which

turned their attention to important new domains or have applied exciting new

analytical frames. The interviews

with Yves Dezalay and Bryant Garth (chapter

20), John Braithwaite and Peter Drahos (chapter 21), and John Hagan (chapter

22), each

focusing in their own way on globalization, are cases in

point.

Even if not a rigorous history in any meaningful sense, it is

difficult not to be impressed by the interplay of forces that have helped

to

generate many major research projects in the field. Rather than reducing

research to an individual enterprise, the interviews

in this book repeatedly pay

a debt to mentors, such as J. Willard Hurst, or the concentrations of colleagues

found at key institutions

in the development of the field, such as the American

Bar Foundation, the University of Wisconsin, Yale University, the Oxford Centre

for Socio-Legal Studies, or yet others. Though merely scratching the surface, by

tracing out the common intellectual and institutional

roots of these empirical,

socio-legal projects, these interviews contribute a deeper appreciation of the

emergence of Law and Society

as a field confident in its ability to contribute

to the understanding of law in action.

Methods and Approach

In our conversations with the scholars in this volume

and with interested colleagues, we could not avoid the recursive suggestion

that

the interviews we were conducting might be put to use in a sociological study of

the sociology of law. Our actual ambitions

were much more modest, but we

nevertheless recognized that it would be supremely ironic if we did not, in a

collection such as this,

turn the spotlight on ourselves long enough to speak in

detail, and with candor, to the methods and approaches we adopted in producing

this book.

The idea for the project was floated over beers at The

Brewer’s Art, an upscale brewpub in Baltimore, where the Law and Society

Association annual meeting was held in 2006. We were already friends, having

worked as Research Fellows at Oxford University’s

Centre for Socio-Legal

Studies. Having previously enjoyed the experience of editing together a

collection of essays,[7]

we set our minds to the conception of another project which would allow us to

work together again. Our own memories of having completed

doctoral research in

the Law and Society tradition were sufficiently recent, perhaps even a little

raw, that we could see the value

of a volume such as this. In particular, for

each of us—in one case a little known, and now fairly old, volume of

reflective

essays[8] and

in the other a review essay based on a close examination of an empirical

project[9]—had

been of such inspiration and comfort to us, respectively, that we were confident

of the pedagogical pay-off of research

narratives over and above the methods

textbooks. Unusually, perhaps, for projects conceived in a brewpub the night

before, we pitched

the idea the next morning to John Berger at Cambridge

University Press—making it seem like it was a well-formed idea, of

course—and

his distinct enthusiasm launched our efforts.

One of our

first decisions was to choose particular projects, rather than authors with an

outstanding corpus of work. That meant

excluding many luminaries and some of our

favorite authors when their individual projects duplicated the approaches and

themes already

selected for inclusion. Our concern for the representativeness of

various methodologies, approaches and subjects meant that many

fine examples of

empirical scholarship, particularly given the depth of excellent ethnographic

fieldwork in Law and Society, could

not be included. Our emphasis on empirical

research projects naturally led us to reject numerous classic pieces that were

based on

keen insight into the empirical world but that did not tell the story

of a discrete

project.[10] Our

process of selection led us to produce a diverse list of works across a wide

time span. However, the selection was complicated

by not knowing what the

response to our invitations would be. We proceeded in waves, prepared to extend

different invitations depending

on the responses. As it happened, the response

rate to our invitations was 100%, so we never drew from our contingent list of

possibilities.

We chose an interview format for the main chapters, rather

than seeking authored essays. We did this for two reasons. First, for entirely

practical reasons, we believed that potential contributors from a wider range of

approaches (and frequently we had specific scholars

in mind) would be more

willing to agree to an interview than to authoring an essay. Second, and more

substantively, we were keen

to capture a more immediate and conversational tone

to the pieces. We instinctively felt that this format would make the book more

accessible and easier to use for readers, creating pieces that can be paired

with the primary texts as a form of commentary and reflection

on the works. We

were keen to establish a contrast to the more prosaic, and at times drier, style

of methods textbooks. We also believed

that capturing something of the spoken

voice of the authors would enliven the narratives and somehow bring them closer

to the reader.

It would help convey the essential humanity of research, an

underlying aim of the volume as a whole. Last, while some useful collections

have provided scholars with narratives about the methodological practices used

in the field,[11] we

knew from more isolated examples and our own experience with interview methods

that interviewing would allow us to ask authors

to “unpack” the

emotional dimensions of their projects or go deeper into various aspects of

their experiences. Interviews

simply allow one to access more spontaneous and

candid answers than an editor giving written comments to a draft of a chapter.

Most of the interviews for the book were conducted at the Law and Society

Association Meeting in Berlin the following year, 2007.

This was a

cost-effective and efficient way of carrying out the work. It was also

exhausting. Before Berlin we had ‘piloted’

the interview approach

with two contributors from Oxford University whom we knew, Keith Hawkins and

Doreen McBarnet. Other interviews,

for pragmatic reasons, were conducted after

Berlin (John Braithwaite and Peter Drahos, John Heinz & Edward Lauman, John

Hagan,

John Conley and William O’Barr, and Alan Paterson). The interview

with John Conley and William O’Barr was conducted by

telephone conference

call, as was the interview with Patty Ewick, though Susan Silbey had been

interviewed in person in Berlin. Although

Bill Felstiner had been interviewed in

Berlin, Austin Sarat contributed answers in writing to an edited text of the

Felstiner interview.

We prepared a set of universal questions which were

asked of all participants and were sent to them in advance of the interviews.

These questions covered issues such as the intellectual background of the

projects, the setting up of projects, how projects were

first intended or

designed, the acts of analyzing and writing up fieldwork, the emotional demands

of the research, and the authors’

reactions to the reception of their work

in the scholarly community. Additionally, we asked numerous questions specific

to the projects

being discussed. Interviews lasted between one and three hours,

with an average of approximately 90 minutes, producing transcripts

of between

approximately 10,000 words and 30,000 words. Our biggest challenge was to edit

those transcripts down to chapters of around

4,000 to 5,000 words. It should go

without saying then, that, without fail, interviews were far richer than this

book could accommodate,

and so we grew in appreciation of the choices that we

were making. Each interview received a two-stage process of editing, with one

of

us doing an initial cut and the other reviewing the edit against the original,

and frequently making considerable changes, both

cutting further and saving some

material from the cutting-room floor. Some interviews suggested a dominant

narrative quite readily,

while others were more chimeric. We chose not to ensure

uniformity of issues addressed across the chapters, but rather to retain

what we

felt were the most interesting and useful aspects of each interview. Having said

that, and as the concluding chapter by Bert

Kritzer highlights, there is still

considerable overlap between chapters in terms of the subjects discussed and

themes which emerge.

It also took us much longer to edit the transcripts than we

had originally anticipated – something, of course, that we should

have

foreseen on the basis of the research narratives we had listened to!

The

authors were promised that we would send the edited transcripts for their

approval. We invited them to amend the text where they

wished, including our

introduction to their chapter, and to suggest methodological keywords to be

included in their chapters. Every

author made some changes to their texts. Most

amendments were minimal. It took considerable nerve for some contributors to see

their

words on the page—what had been said in the comfortable and relaxed

atmosphere of Berlin—and to not shrink from our call

to allow their

doubts, mistakes, and reflects to go forward to press. We thank them for their

fortitude.

The one exception to our decision to conduct interviews is the

concluding chapter authored by Bert Kritzer, which pulls together the

insights

from the interviews in aggregate and reflects on the state of law and society

research. Bert Kritzer struck us as, perhaps

without peer, the scholar most

qualified to reflect on the reflections. The editor of Law & Society

Review from 2003 to 2007, and co-editor (with Peter Cane) of the Oxford

Handbook of Empirical Legal Studies, for the past three decades he has been

one of the leading producers and consumers of empirical Law & Society

research. In particular,

he has long taken a reflexive interest in the

research process, and has written much about how empirical research projects

have come

to pass.

The last matter to be decided in the production of the

book was how to title it. One of us is more demanding than the other (in a

good

way, it is hoped) regarding titles, asking that they be catchy and

memorable.[12] In

these interviews, we frequently asked authors how their books and articles got

their titles, and some of those answers made it

through the editing (see, e.g.,

Feeley, Chapter 4; Engel, Chapter 8; and Rosenberg, Chapter 15;). We struggled

to title this book,

having so many concepts and themes seemingly at play. One of

our colleagues early on gave us the promising suggestion of “Law

and

Society in Action,” a clever twist on an old theme, and we ran with it for

months. “Beyond Methods” was also

considered, later in the process.

Both fell afoul of the judgment of our editor at Cambridge, who sensibly advised

us that a plain

and descriptive title sells more books by giving readers and

libraries a better sense of why they need the book. The title and subtitle

of

this chapter, like gravestones for dead ideas, memorializes our journey through

the difficult job of naming one’s projects.

Organization of the Book

This book is not designed to be read cover-to-cover,

and so in some respects the order of the material may be irrelevant. In our

formal

proposal to Cambridge University Press we had suggested organizing the

book into sections reflecting the various research techniques

used and the

traditional subject foci of the Law and Society field. This would have mirrored

the approaches taken to research methods

textbooks and to various Law and

Society Readers. Several attempts in this vein left us frustrated that this

approach might obscure

more than it revealed for a volume such as this.

Particularly where single projects have used multiple methods, separating

chapters

out according to individual techniques would be problematic. Further,

in a developing field where research questions and analytical

constructs build

on and re-frame prior work, and where path-breaking work embraces and extends a

range of traditional themes, it

seems counter-productive to reduce projects to

one, or even a dominant, research concern. So serendipity intervened, just as

Figure

1 suggests it should—when attempting to place one’s data

alongside the conceptual framework—and we devised a new,

more satisfying

order of the chapters. The interviews, accordingly, follow a chronological

sequence according to the date of publication

of the main research publication

being discussed.[13]

In the end, the chronological frame helped us see the interviews in a way that

confirms an initial hypothesis: that uncertainty

and ambiguity are not products

of a particular age of a field, when it is new, but are ever-present. Hopefully

these interviews

will help lessen the anxieties that attend this condition.

[1] For other

personal accounts of the draw of socio-legal studies for lawyers, see Bradney, A

(1998) ”Law as a Parasitic Discipline

Journal of Law and Society,

vol. 25, no. 1, pp. 71 – 84; Cotterrell, R. (2002) ”Subverting

Orthodoxy, Making Law Central: A View of Sociolegal Studies”

Journal of

Law & Society, vol. 29, no, 4, pp.

632-44

[2] Lee

Epstein and Gary King, “The Rules of Inference,” University of

Chicago Law Review, vol. 69, no. 1 (2002), pp.1-133. See also, Robert

Spitzer, Saving the Constitution From Lawyers (New York: Cambridge University

Press, 2008), pp. 1-55.

[3] W. H. Auden,

The Dyer’s Hand and other essays (London: Faber and Faber,

1963), p.47

[4]

Philippe Schmitter, “The Design of Social and Political Research”,

in Approaches and Methodologies in the Social Sciences, Donatella Della

Porta and Michael Keating, eds. (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press,

2008), p. 294, Figure

14.3.

[5] See, for

example, Felice J. Levine, “Goose Bumps and ‘The Search for

Intelligent Life’ in Sociolegal Studies: After

Twenty-Five Years”

Law & Society Review vol. 24(1):7-33 (1990); and Bryant Garth and

Joyce Sterling, “From Legal Realism to Law and Society: Reshaping Law for

the

Last Stages of the Activist State,” Law & Society Review

32:409-71 (1998). For accounts of the development of socio-legal studies in the

UK, see Philip A. Thomas, ‘Socio-Legal Studies:

The Case of Disappearing

Fleas and Bustards’ in Thomas, ed., Socio-Legal Studies (Aldershot,

Dartmouth, 1997); and William Twining, “Remembering 1972: The Oxford

Centre in the Context of Developments in Higher

Education and the Discipline of

Law” Journal of Law and Society, vol. 22:35-49 (1995). See,

generally, Encyclopedia of Law & Society: American and Global

Perspectives, David S. Clark, ed., (Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications,

2007).

[6] But see,

Carroll Seron, ed., The Law and Society Canon (Aldershot, Ashgate, 2006);

and Seron, C. and Susan S. Silbey, “Profession, Science and Culture: An

Emergent Canon of Law and

Society Research,” in The Blackwell Companion

to Law and Society, Austin Sarat, ed., (Oxford: Blackwell, 2004) pp.

30-59.

[7] Human

Rights Brought Home: Socio-Legal Perspectives on Human Rights in the National

Context (Oxford: Hart Publishing,

2004).

[8] Robin

Luckham, ed., Law and Social Enquiry: Case Studies of Research (Uppsala:

Scandinavian Institute of African Studies,

1981).

[9] Herbert M.

Kritzer, “ ‘Data, Data, Data, Drowning in Data’: Crafting

The Hollow Core”, Law and Social Inquiry, 21:761-804

(1996).

[10] A

prime example is Marc Galanter’s, “Why the ‘Haves’ Come

Out Ahead: Speculations on the Limits of Legal

Change,” Law &

Society Review 9:95-160

(1974).

[11] June

Starr and Mark Goodale, eds., Practicing Ethnography in Law: New Dialogues,

Enduring Methods (New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan,

2002).

[12]The

other, having once been told by a colleague that he had conjured up the

“second-worst titled book in academia”, has

long-since abandoned

pride in the titling

process.

[13] A

number of authors produced additional outputs from the same projects. Details of

these are given at the beginning of the chapters.

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/UNSWLRS/2009/36.html