University of New South Wales Faculty of Law Research Series

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

University of New South Wales Faculty of Law Research Series |

|

Last Updated: 26 August 2010

Sustaining Growth in Developing Economies through Improved Taxpayer Compliance: Challenges for Policy Makers and Revenue Authorities

Margaret McKerchar and Chris Evans [1]

Citation

Paper presented at 21st Australasian Tax Teachers Annual Conference University of Canterbury, 20-21 January 2009.

Abstract

The existing body of literature on taxpayer compliance has developed over some 30 years or more and has predominantly emanated from developed economies including the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada and Australia. Over the same period many developed economies have made considerable investment in legislative tax reforms, taxpayer education programs, tax enforcement strategies, and increasingly sophisticated systems of tax administration using new technologies. Undoubtedly there are lessons to be learnt from studying best practice in developed economies.

However, compared to their counterparts in developed economies, policy makers and revenue authorities in developing economies face quite different challenges and constraints that require careful consideration in designing appropriate and effective tax systems. In particular, the tax system in a developing economy must foster sustainable economic growth, ensuring that the necessary revenue collections are made to provide for political stability, investment in infrastructure and improved standards of living. Typically developing economies have both limited administrative resources and expertise. Tax administration is generally weak, with widespread evasion, corruption and coercion. Further, taxpayers tend to have low levels of literacy, low tax morale and negative attitudes towards government. The cash economy, and its inherent opportunities for engagement in fraud and tax evasion, often plays a major role in developing economies.

This paper explores these challenges and constraints in developing economies. It uses Nigeria as a case study, and identifies the strategies considered to be most effective in improving both personal and corporate taxpayer compliance and the necessary steps to implement them in order to achieve sustainable economic growth.

1 INTRODUCTION

Taxes, and tax systems, are fundamental components of any attempts to build nations, and this is particularly the case in developing nations. As Brautigam has noted, “[t]axes underwrite the capacity of states to carry out their goals; they form one of the central arenas for the conduct of state-society relations, and they shape the balance between accumulation and redistribution that gives states their social character”.[2] In short, taxes build capacity (to provide security, meet basic needs or foster economic development) and they build legitimacy and consent (helping to create consensual, accountable and representative government).

A key component of any tax system is the manner in which it is administered. “No tax is better than its administration, so tax administration matters – a lot”.[3] And an essential objective of tax administration is to ensure the maximum possible compliance by taxpayers of all types with their taxation obligations. Unfortunately, in many developing countries, tax administration is “usually weak and characterised by extensive evasion, corruption and coercion. In many cases overall tax levels are low, and large sectors of the informal economy escape the tax net entirely”.[4]

A considerable body of literature and much ‘best practice’ knowledge and experience currently exists in respect of both tax administration and taxpayer compliance. This is understandable given the fundamental contribution that taxation makes to the achievement of the many goals (including economic and social) of governments and their constituents. However, the reality is that much of this literature, knowledge and experience has emanated from developed economies and the extent to which they apply to developing economies is uncertain. Given this gap of knowledge, together with the fact that tax administration is one of the most important but least studied aspects of fiscal reform in developing economies,[5] there appears considerable scope for further research.

The purpose of the paper is to identify the most appropriate and effective strategies to improve taxpayer compliance in developing countries. This is an ambitious task as taxpayer compliance in itself is a complex phenomenon that takes place in a dynamic environment with many factors at play including tax policy and tax administration. It uses the example of Nigeria to illustrate its central points, but considers that the principles have broader application to other developing countries. Nigeria has recently released a Draft National Tax Policy aimed at providing direction for the Nigerian tax system in order to “stimulate the economy in a way that will be of benefit to all Nigerians”.[6] That is, there currently exists in Nigeria recognition of the need to engage in tax reform at all levels of government in addition to the expressed desire to develop a set of guiding principles built on stability, accountability, equity and centralised authority. Given Nigeria’s reform agenda, the identification of appropriate and effective strategies to improve taxpayer compliance is timely.

The balance of the paper is presented in four parts. Following on from this introduction, Part 2 of the paper presents an overview of the taxpayer compliance literature and presents findings on how behaviour is influenced by a range of strategies commonly adopted by revenue authorities. The underlying challenges for policymakers are also considered. The intent of this part is to be both broad and general in its approach and not be necessarily constrained by domestic, economic or other considerations. In Part 3 of the paper the Nigerian tax system is discussed including consideration of its challenges, capacity and proposed reforms. Together Parts 2 and 3 of the paper provide the context for Part 4 in which the strategies for improving taxpayer compliance that are considered most appropriate to Nigeria are identified and discussed. Some concluding comments on tax policy, tax administration and tax compliance are made in the fifth and final section of the paper, in addition to the identification of areas where further research may be fruitful.

2 FACTORS AFFECTING COMPLIANCE

2.1 Obligations and managing risk

The fundamental goal of any revenue authority is to collect taxes and duties payable according to the law. However, when it comes to the obligations imposed on them by law, taxpayers are not always compliant. A compliant taxpayer is one who fulfills every aspect of their tax obligations including:

A non-compliant taxpayer is one who fails to satisfy any one or more of these aspects and poses a risk to revenue collection. Research has shown that non-compliance may be as a result of a deliberate decision by the taxpayer, or it may be unintentional.[8] Further, there is a range of possible compliance outcomes driven by a variety of factors including demographic (including age, gender and level of education), personal (including attitudes, experiences, morale and financial circumstances) and aspects of the tax system itself (including tax rates, penalties, audit probabilities, enforcement strategies, complexity and costs of compliance). As many of these factors are not constant, it is to be expected that compliance behaviour can change over time and a compliant taxpayer one year may be non-compliant the next.

From the perspective of the revenue authority, the ideal is to have all taxpayers fully compliant at all times. If this were the case, the tax gap (the difference between what a revenue authority theoretically should collect and what it actually does collect) would not exist. The ideal is obviously not attainable. But to be able to work towards this ideal, the revenue authority needs to be able to identify and understand the various types of compliance outcomes and then develop and apply appropriate strategies to modify (or reinforce) taxpayers’ behaviour accordingly. As the revenue authority normally has limited resources at its disposal, it needs to be strategic if it is to be efficient and effective in managing its risks. This will require the authority to identify and prioritise its risks, to tailor and target specific activities to each identified risk, and to allocate resources accordingly. This is commonly referred to as a risk management approach to compliance and is widely adopted in many jurisdictions, and in particular, where taxpayers are required to self-assess their tax liability.[9]

The 2004 OECD report notes that “the benefits of pursuing a risk management approach are well established. For a revenue authority they include:

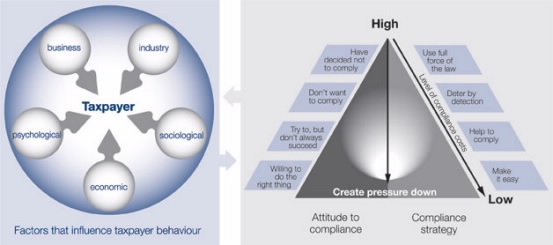

The Australian compliance model (see Figure 1)[11] is typical of the models currently being operated by revenue authorities in many developed countries. The models are based on the premise that the revenue authority can influence behaviour through its responses and interventions. The focus is upon the causes rather than the symptoms of non-compliance, requiring an understanding of the business, industry, sociological, economic and psychological factors that drive taxpayer behaviour.

The model’s core principle is to make compliance (including access to entitlements and benefits) as easy as possible for those who want to comply. At the other end of the spectrum, the full force of the law is applied when taxpayers willfully seek to abuse the system.

Figure 1: The Australian Taxation Office compliance model

The underlying assumption in the risk management approach is that all risks can be identified and measured to some extent. The reality is likely to be quite different. The discussion that follows serves to illustrate that there are many dimensions to compliance behaviour and that it is a complex and multi-dimensional problem. A standard solution to the problem has thus far proved to be elusive and it continues to pose a formidable challenge to tax administrators globally.[12] Following is a review of what is known about taxpayer compliance behaviour and how it may be influenced by many of the various strategies commonly used by revenue authorities.

2.2 Understanding compliance behaviour

Over the last thirty years or so, a considerable body of literature has developed in the area of taxpayer compliance from which has emerged two significant and widely accepted findings. Firstly, taxpayer non-compliance is a continual and growing global problem that is not readily addressed. Secondly, despite a great deal of research emanating from a wide variety of disciplines, there is not a great deal of consensus about why people do, or do not, pay their taxes or otherwise comply with their tax obligations. Nonetheless, strategies to improve compliance need to be embedded in sound theory, so an understanding of the compliance literature is an important starting point for the revenue authority seeking to improve the efficiency of its collections. [13]

Models and theories of compliance behaviour tend to reflect one of three schools of thought commonly referred to as economic deterrence, social psychology, and fiscal psychology (the latter representing an evolution of the other two).

Economic deterrence models

Economic deterrence models[14] in general are based on the theory that behaviour, in a wide range of contexts including tax evasion, is responsive to punishment or sanctions. Economic deterrence models tend to have a narrow, theoretical view of behaviour, reducing its dimensions to numerical measures and assigned probabilities from which outcomes can be predicted using calculus. In order to determine behaviour in this manner, economic deterrence models tend to rely upon a wide range of fundamental assumptions that are generally unrealistic. For example, that all people respond to a change in any one variable in an identical and predictable manner; that all taxpayers have a full knowledge of the probability of being audited; and that all taxpayers have the same level of risk preference. Although empirical testing has been limited, the theoretical principles of economic deterrence have been widely adopted by tax administrations in developing enforcement strategies that rely principally on penalties and the fear of getting caught.

There is evidence to support the relevance of deterrence strategies to addressing non-compliance, but it appears that their impact may not be captured by a single mathematical expression. For example, the fear of getting caught, or the probability of detection, has been found to be an effective strategy to induce truthful reporting where the assumption that taxpayers were risk neutral was relaxed.[15] Further, in an Australian study it was found that individual tax evasion behaviour was not solely determined by the monetary value of expected gains, but that ‘moral’ factors also influenced this decision.[16] These results suggest that the economic deterrence models have relevance to compliance behaviour, but that there are other influences to be considered.

Social psychology models

Social psychology models are concerned with the

prediction and understanding of human behaviour, or how people make decisions,

using

a range of methodological approaches including compositional modeling,

attribution theory and equity theory.

Compositional modeling is characterised

by the view that individuals undertake deliberate and reasoned action according

to their personal

preferences.[17] This

approach assumes that people consider the implications of their actions before

they decide, or form an intention, to engage

or not engage in a given behaviour.

Further, this approach assumes that intention directly translates into

behaviour, without any

further influences. The model then seeks to explain how

intention is formed.

According to the theory of reasoned action, an individual’s intention is a function of two basic determinants, one personal in nature and the other reflecting social influence. The personal factor is the individual’s attitude toward the behaviour and is assumed to be either positive or negative. The second determinant of intention is the subjective norm, or the person’s perception of the social pressures to perform or not perform the behaviour in question. Generally, individuals will intend to perform a behaviour when they evaluate it positively and believe that others (whose opinion they value) think they should perform it. In testing this theory in the context of tax evasion it was found that the intention to comply could be improved by directly communicating to taxpayers their personal and social responsibilities.[18]

Attribution theory is based on the assumption that individuals rationally interpret and analyse events in order to understand causal structures.[19] People have internal (personal) and external (situational) attributes. In judging the behaviour of others, people will generally attribute the outcome as being caused by their own internal attributes. In judging their own behaviour, people tend to believe the cause is due to external attributes. For example, he is a tax evader because he is a bad person; I am a tax evader because the government wastes my taxes (and that’s not my fault).

These social psychology models highlight the importance of equity theory in the study of compliance and taxpayer behaviour. Equity theory proposes that individuals are more likely to comply with rules if they perceive the system that determines those rules to be equitable. Where there are perceived inequities, individuals will adjust their inputs to the exchange until equity is restored. Based on equity theory, addressing inequities in the exchange relationship between government and taxpayers would result in improved compliance.[20]

Fiscal psychology models

Fiscal psychology models draw on both the economic deterrence and the social psychology models and generally view tax enforcement as a behavioural problem, one that can be resolved by co-operation between taxpayers and tax collectors. To obtain this co-operation, the role of the tax system itself in providing the positive stimulus (such as decreasing penalties) is emphasised. This stimulus is then expected to generate a more positive attitude in taxpayers that will in turn impact on their compliance decisions.

The fiscal psychology models place considerable emphasis on taxpayer attitude. It has been held that tax mentality, feelings of tax tension, and tax morale were the three psyches that together made up a taxpayer’s attitude. The more positive the taxpayer’s attitude towards paying tax the greater the level of co-operation with the tax authority and the greater the willingness to pay tax.[21] However, fiscal ignorance may be a negative influence on a taxpayer’s attitude.[22] Further, there is evidence to suggest that the threat of sanctions is a negative influence on taxpayers in low socio-economic groups and that appeals to conscience are less effective than the threat of sanctions on taxpayers in high socio-economic groups.[23] It has also been found that in the case of taxpayers with low moral reasoning, appealing to their sense of morality is unlikely to be effective.[24] However, research has found that carefully tailored persuasive communication strategies can impact on taxpayer reporting, at least in the short-term.[25]

Based on studies in Switzerland, Belgium and Spain, trust in the legal system, government, or parliament; national pride; and pro-democratic attitudes all have a positive effect on tax morale and support the finding that higher legitimacy for political institutions leads to higher tax morale.[26] Further, there is evidence, based on a study of 30 developed and developing countries (although primarily non African), that tax compliance is highest in the countries characterised by high control of corruption and low size of bureaucracy.[27]

In a study by Song and Yarborough[28] it was assumed that a high level of tax ethics (on the part of taxpayers) was a prerequisite for a fair and successful tax administration, particularly one that was based largely on voluntary compliance. They argued that voluntary compliance was determined by three major factors: the overall legal environment, the citizen’s tax ethics, and other situational factors operating at a particular time and place. It was found that people with higher income levels and high levels of education had higher ethics. However, the extent to which ethics (which could be aligned with intention under the theory of reasoned action) determines actual behaviour is unclear.

A study into the extent to which unfairness was the basic cause of dissatisfaction with the tax system in the State of Oregon found that fear of informal sanctions (from peers, from community and from the stress of getting caught) was one of the most powerful predictors of conformity with tax laws.[29] A study into income tax evasion in Australia found that 86 per cent of evaders surveyed considered that the level of income tax in relation to the level of government services was excessive. Further, the burden of tax was regarded as not shared fairly and the rates of tax were perceived to be too high.[30]

In a US study into income tax compliance,[31] the effects of audit rates, penalties, other tax administration policies and socio-demographic factors on tax compliance were examined. It was concluded that an increased probability of audit, increased use of first and second notices of taxes due and increases in criminal penalties all generally led to increased level of compliance. Further, education of taxpayers appeared to increase compliance.[32] Results in respect of enforcement were mixed, but they did indicate that increased levels of activity in these areas were associated with decreased rather than increased compliance. Dubin[33] studied the impact of criminal investigations (in the case of money laundering) on taxpayer compliance and found that they have a positive effect on general deterrence. For those taxpayers engaged in illegal activities, the threat of imprisonment was found to be a more effective deterrent than were monetary penalties. Further, Dubin argues that the media can play an important role in disseminating information to the public and thereby improving voluntary compliance. This concept is referred to by Alm et al[34] as the indirect deterrent effect of audit. Alm et al found that ‘unofficial” communications have a strong indirect effect that increases compliance, but that “official” communications may not encourage voluntary compliance.

Smith and Kinsey developed a useful conceptual framework of tax compliance that incorporated three key points: in a complex tax system, compliance was as problematic as non-compliance; individuals have different opportunities for performing particular acts; and that tax behaviour did not necessarily involve conscious decisions.[35] It was argued that the assumption that had dominated earlier models, that non-compliance was a result of considered choices and conscious decisions by taxpayers, was neither appropriate nor needed. Some compliance may be unintentional, simply the result of indifference or habit. It was recognised that the strategies utilised to reduce intentional non-compliance may not be the most effective strategies to reduce unintentional non-compliance. This argument, viz. that compliance and non-compliance could not be understood as unitary phenomena, and therefore policy and enforcement strategies would be more effective if directed to address specific compliance behaviour, has continued to be reinforced in the literature.[36]

Clearly, understanding taxpayer compliance remains a challenging and unresolved problem. A large part of the problem appears to have been the search for one overarching model of taxpayer compliance that allowed predictions to be made about the taxpaying population as a whole. Realistically, the later typology-type fiscal psychology models offer more guidance for revenue authorities seeking to improve voluntary compliance in a dynamic environment. That is, different strategies are more appropriate for different types of taxpayers, but that an understanding of the various types of taxpayers underpins the choice of strategies. Again, this approach is consistent with the tax risk management approach advocated by the OECD and is practised today by many leading tax administrations.[37] However, as noted by Kornhauser in the context of the United States, further behavioural research is still needed and together with educational efforts aimed at all segments of the population to improve taxpayer knowledge, attitudes and behaviour, holds much promise for improving voluntary compliance.[38] These needs are not unique to the United States and could be said to be equally applicable to any tax administration, and particularly those that rely on self assessment.

2.3 Challenges for policymakers

What emerges from the literature is that there are no quick fixes to improving taxpayer compliance. Instead, what is required is a concerted, long-term coordinated and comprehensive plan that uses a complimentary range of policy instruments underpinned by a solid legal base.[39] This highlights the importance of tax policy and other aspects of tax systems design that provide the framework within which the revenue authority has to perform its responsibilities. In reality it makes sense for policymakers to identify and address the underlying and systemic challenges of their tax systems before the respective revenue authorities considers how to manage their resources and discharge their responsibilities.

The desirable features of a tax system are generally considered to be equity (fairness), certainty (simplicity), convenience of payment and economy in collection (efficiency).[40] However, it is recognised that these features are conflicting and that policymakers have to repeatedly choose between simplicity and efficiency, or fairness and simplicity, or fairness and efficiency.[41] For example, a simple, efficient system with a high degree of certainty is unlikely to be entirely equitable. A simple system should facilitate high levels of voluntary compliance and be more efficient as a result. That is, at the outset policymakers must consider the necessary trade-offs of these features and determine the desired balance that is appropriate to the given context.

Typically simplicity in a tax system is sought but this gives rise to the dilemma of identifying what is a simple tax system and how it can best be achieved. Structural simplicity (for example) can be improved by measures including minimising both the number of different taxes and the number of different rates. Structural simplicity can reduce both compliance costs for taxpayers and the costs of tax administration. However, structural simplicity (in spite of its attractiveness) may have a negative impact on vertical equity. In the case of developing economies, Bird and Casanegra de Jantscher set out that, as a rule, an essential precondition for the reform of tax administration is the simplification of the tax system to ensure that it can be applied effectively given the generally ‘low compliance’ contexts.[42]

The lack of legal simplicity (i.e. tax law complexity) has been identified as the single greatest problem facing taxpayers and tax administrators[43] and has many causes including drafting style, language, and volume.[44] It is a perennial problem as taxpayers facing self assessment require greater certainty. It also makes enforcement more difficult. However, tax law complexity does not just arise from the expression of the law but can occur because of the underlying policy in itself is complex. That is, the less complex the policy the greater the likelihood of being able to develop law that can be readily applied. Policy is the fundamental starting point or first stage in having a simple tax system.

Simple policy (or at least as simple as possible) needs to have clearly articulated objectives and be integrated with other aspects of the tax system. In developing policy, the application of the policy must be considered and this will require consultation with its intended users and drafters. Policymakers need to consider the volume of legislation and the rate of change as complicating factors and seek to minimise them (for example, by moving away from ‘black letter’ law). Simple policy then must then be translated into legislation (second stage), the purpose of which must be transparent and clearly communicated to the drafters. The drafters must then produce legislation that users (including taxpayers, tax administrators and the judiciary) can apply (third stage) efficiently, consistently and with certainty. In doing so, both compliance and administrative costs can be minimised and simplicity best achieved.

In terms of practice, Arnold[45] described the integrated policy of the formulation of tax policy as having three major components – policy development, technical analysis and statutory drafting – and argued that the three functions are so closely interrelated that the entire process would suffer if performed by different parts of the government bureaucracy. However, the tax policy function should be separated from the tax administration and enforcement function (but there needs to be effective communication). Separation of policymakers and tax collectors results in a system of checks and balances which protects the interests of taxpayers and the government. There is a danger that policymakers are often so taken with the theoretical purity of their proposals that they do not pay sufficient attention to the compliance and administrative aspects of the proposals. Approaches to simplify tax law that have failed in developed economies (such as Australia, the United States and the United Kingdom) have done so because they did not adequately develop tax policy in the context of wider economic reforms.[46]

In the case of developing economies undertaking tax reform, Bird and Casanegra de Jantscher argue the need to have a strategy or comprehensive plan that assigns clear priorities to the tasks that must be performed, tailored to the available resources. The scarcity of resources is a common constraint and reform strategies that require substantial additional administrative resources are doomed to failure simply because the resources are unlikely to materialise fully or in a timely fashion. Instead, more efficient alternatives (such as eliminating unproductive tasks or simplifying procedures) need to be pursued.[47] Further, Bird and Casanegra highlight the importance of a robust management information system together with the streamlining of systems and procedures in reforming tax administration.[48]

This part of the paper has identified broadly and generally many of the issues affecting taxpayers, revenue authorities and tax policymakers today. Before analysing the implication of these issues for identifying strategies to improve taxpayer compliance in Nigeria it is necessary to consider the Nigerian tax system, and its current proposals for tax reform, in some detail. This – in turn – will permit the identification of the full range of compliance challenges that Nigeria is currently facing and underpin the development of suggestions to deal with those compliance challenges.

3 THE NIGERIAN TAX SYSTEM

One striking characteristic of the Nigerian tax system is its heavy reliance on the petroleum industry (through the Petroleum Profits Tax (“PPT”) and royalties) for a significant proportion of its tax revenue, both in absolute and relative terms. In 2005 Gallagher suggested that “80% of Federal Government revenues in Nigeria is derived directly from the oil sector”.[49] The 2008 Draft Document on the National Tax Policy[50] shows that this is only 55% of total tax revenue (i.e. from federal, state and presumably local taxes), but this is still a very significant proportion. Table 1 indicates the principal components of Nigerian tax revenue in comparison with three comparable African nations.

Table 1 Components of Total Revenue in Major African Economies (%)

|

Tax as a % of Total Revenue

|

Nigeria

|

Ghana

|

Kenya

|

South Africa

|

|

Personal Income Tax

|

0

|

11

|

20

|

31

|

|

Corporate Tax

|

15

|

13

|

19

|

24

|

|

VAT

|

12

|

25

|

47

|

28

|

|

Customs & Excise

|

18

|

18

|

9

|

8

|

|

Petrol taxes and other

|

55

|

33

|

5

|

9

|

|

Total

|

100

|

100

|

100

|

100

|

Source: Adapted from Presidential Committee on National Tax Policy, Draft Document on the National Tax Policy, Draft 1.1 16 July 2008, at page 34.

As can be seen from the table, the other principal components of tax revenue in Nigeria are Corporate Income Tax (“CIT”), Value Added Tax (“VAT) and a variety of Customs and Excise duties and levies. The CIT operates on a classical basis whereby corporate profits are charged at the level of the company and distributed dividends are separately subject to a withholding tax. CIT is charged at the standard rate of 30%, although companies in many industries (manufacturing, agricultural production, certain mining and export trades) whose turnover is less than NGN 1 million may be eligible for a 20% rate. Corporate capital gains are taxed at 10%.

The VAT was introduced in 1993 and has always been charged on taxable goods and services at the single rate of 5%. Exports are exempt from VAT as are medical services and products, basic food items, books and educational materials, newspapers and magazines, commercial vehicles and spares, and various items of plant and machinery used in agriculture and the gas and petroleum industries. The 5% rate is low by African standards – the VAT rates for other Economic Community of West African States (“ECOWAS”) in 2006 generally varied between 15% and 19%.[51]

The Personal Income Tax (“PIT”) is levied on individuals in receipt of income from sources inside or outside Nigeria. With certain exceptions (see later) the PIT is levied in the state in Nigeria in which the individual is deemed to be resident in the (calendar) year of assessment. PIT is charged on a progressive basis after personal allowances (5,000 NGN plus 20% of earned income) at rates of between 5% and 25%, subject to a minimum tax charge of 0.5% of total income. Capital gains are charged at 10%. As can be noted from Table 1, the PIT produces negligible tax revenue.

The need to review the performance of the Nigerian tax system has been attributed to the negative economic impact of persistent fiscal deficits that have occurred primarily because of the inadequacy of the revenue base to cope with the targeted level of economic activities.[52] This situation (i.e. deficit financing) is not unique to Nigeria and is indeed common to many developing economies.[53] At the outset it is important to recognise that the tax system needs to reflect the goals of the economy and that these will change over time. For example, during the colonial period and immediately after the Nigerian (political) independence in 1960, the sole objective of taxation was to raise revenue. The emphasis then shifted to the protection of infant industries and income redistribution.[54] In the current Draft Document on the National Tax Policy the objectives of the Nigerian Tax System have expanded and are identified as:

Further, the fundamental features to be exhibited by all taxes within the Nigerian Tax system include:

Similar to many other countries that were formerly British colonies including Australia, Nigeria has three tiers of government (federal, state and local) each with (in theory) different taxing powers and responsibilities for certain categories of expenditures.[56] It appears that in the past there has been an emphasis on continued financial independence of each tier of government (as underpinning political stability and social harmony of the nation).[57] In practice there has been illegal multiple taxation (i.e. same tax applied at multiple levels of government contravening the law) and a proliferation of taxes that have posed challenges (and costs) for revenue authorities and taxpayers (particularly in respect of the lack of certainty) alike. Indeed the burdens of administration and collection of taxes in Nigeria were recently described as one of the worst in the world[58] and the tax system described as woefully lacking in the required manpower, infrastructure and technology.[59]

In particular, local governments (of which there are 774) in Nigeria have often paid scant regard to the provisions of the law in respect of their taxing powers.[60] In the past this may have been attributed to deficiencies in the legal framework and policy orientation of the federal, or central government.[61] However, the recent decision of the Court of Appeal in Eti-Osa Local Government v. Jegede and another[62] held that, under the Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria (1999), the federal government alone had the power to determine and legislate on the kind and quantum of taxes that should be imposed by each tier of government.[63] This decision, the first that has tested the relevant decree,[64] is expected to resolve what has been a contentious issue in respect of the taxing powers of local government.[65]

For state governments, wielding the power to tax appears to have been less contentious. State governments, each of which has its own Board of Internal Revenue (there are 36 State Boards), collected sales tax until it was replaced by a VAT in 1994.[66] The introduction of VAT was one of the recommendations of a Study Group set up by the federal government in 1991 to undertake a comprehensive review of the Nigerian tax system (at both state and federal levels). The introduction of VAT was in response to the federal government’s desire to widen the tax base, promote uniformity and enhance collection efficiency.[67] However, noncompliance with VAT and corruption have both been problematic[68] and this is of concern given the negative impact of corruption on taxpayer morale and, in turn, on compliance.[69]

Other reforms that were recommended by the Study Group and subsequently adopted included the introduction of a uniform PIT system and a self-assessment system.[70] Tax reforms of this nature, and in particular widening of the base and flattening of tax rates, are widely evident in developed countries and becoming increasingly evident in developing countries.[71] Self assessment is becoming increasingly more evident globally[72] but it does bring particular challenges for all stakeholders given its fundamental reliance on voluntary compliance. Self assessment is more likely to succeed where the tax system is simple both for taxpayers to understand and for the revenue authority to administer. That is, fewer taxes, straightforward rate structures and laws (and secondary materials) that are readily understood can give taxpayers certainty and reduce the discretionary powers of the revenue authority and thereby have a positive impact on the level of voluntary compliance in a self-assessment environment.

In 2002 the Minister of Finance set up a further Study Group to review the Nigerian tax system followed by a Working Group in 2004 to review the Study Group’s recommendations. The recommendations of both the Study and the Working Groups were reviewed by various stakeholders and have led to the formulation of the Draft National Tax Policy by the Presidential Committee on National Tax Policy. Circulation of the Draft National Tax Policy document, developed by the Presidential Committee which was established in 2005, indicates that Nigeria is committed to effective tax reform, interactive discourse with its stakeholders and greater accountability.[73] Further, there appears to be a willingness to engage key stakeholders in the formal economy, in particular, the petroleum sector which is regarded as critical to Nigeria’s economic and social performance.[74]

Further evidence of this commitment is apparent in the restructuring (and streamlining) of the tax administration. The former Federal Board of Inland Revenue (“FBIR”) was first created in 1961 to assess, collect and account for all taxes under its jurisdiction in Nigeria. The Federal Inland Revenue Service (“FIRS”) was then the operational arm of the Board and carried out the statutory functions of the Board including the assessment, collection, and accounting of the following eight taxes:

(i) PPT;

(ii) CIT;

(iii) Stamp Duties;

(iv) Capital Gains Tax (CGT);

(v) PIT[75] of

• Armed Forces Personnel and the Police,

• External Affairs Officers (i.e. The Nigerian Foreign Service),

• Residents of the Federal Capital Territory;

• Non-residents deriving income or profits from Nigeria;

(vi) VAT;

(vii) Education Tax; and

(viii) Back duty Penalties and Pre-operation levy.

However, the FBIR was dissolved in 2007 and FIRS was established as an autonomous body reporting to the Minister of Finance.[76] VAT offices have been absorbed into FIRS structure and increasing centralisation of the Nigerian tax system is becoming more apparent. Other recent changes include the broadening of the investigative powers of the FIRS and the strengthening of penalties (including imprisonment) for false declarations and unpaid taxes. State Boards of Internal Revenue remain in place (reporting directly to the Minister of Finance) and local government councils will retain specific taxing rights and responsibilities. Further, it has been announced that taxpayer identification numbers (“TINs”) are to be issued to every taxable person in Nigeria by the FIRS (i.e. centrally) rather than in the case of most individual taxpayers, by the State Revenue Boards as had been the case previously.[77]

In reality the FIRS has been undergoing considerable administrative reforms since 2004. Apart from the statutory change discussed above, there have been many internal changes aimed at clarifying its mission, values and goals; streamlining its structure; addressing systemic corruption; and securing funding (based on a percentage of its non-oil tax collections rather than relying on budgetary provisions) to drive capacity (staff recruitment and staff training being key features of this capacity).[78] These changes may be potentially very influential in respect of the legitimacy of government, the integrity of the revenue authority and the morale of taxpayers. They do appear to be reflective of cautious and considered change.

Finally, the role of the Joint Tax Board (“JTB”) needs to be considered in the light of the strengthening tax reform agenda in Nigeria. The JTB is an umbrella organisation that was first established by the Personal Income Tax Decree in 1993. The purpose of the JTB was to harmonise the tax activity of the three levels of government. The JTB was chaired by the Chairman of FBIR and all Chairmen of State Boards of Internal Revenue were members of the JTB. The Court of Appeal in Eti-Osa Local Government v Jegade and another[79]noted that the establishment of the JTB was a good attempt at coordinating the types and nature of taxes imposed by the various levels of government in Nigeria and that (in furtherance of the constitution), all taxes chargeable should be channeled through the JTB.[80]

However, according to the Draft Document on the National Tax Policy, it is proposed that the Ministry of Finance will be the body charged with providing the oversight function of the revenue authorities in Nigeria and the sole organisation responsible for tax policy matters. Further, no government ministry or organisations or person will have the authority to introduce new taxes without following due process i.e. through the Federal Ministry of Finance.[81] It therefore appears that the role of the JTB is to be somewhat refined in that it has no direct reporting relationship with the Federal Ministry of Finance, although it may play an advisory role to government, should its opinion be sought. It is further proposed that the JTB co-ordinate the shared activities (primarily PIT) of the federal and state revenue authorities and provide technical assistance and support to the State Boards of Revenue. However, it is proposed that the JTB will have legal powers to function as a policy making body for those taxes for which the administration is split across States, although all decisions of the JTB are subject to the approval of the Minister of Finance.

It is clear that Nigeria has made considerable progress, in the period since 1999 and particularly in the last six years, in identifying a policy framework and beginning the process for the development of a tax system that can provide the revenue capacity and the state-building legitimacy that is desperately needed. But the challenges are still significant. Accompanying documentation to the 2008 draft of the National Tax Policy frankly notes that Nigeria’s past experience with respect to the administration of taxes has been typified by sub-optimal administration, multiplicity of taxes, uncertainty, low levels of compliance and high costs of collection.[82] The theme of low levels of compliance is confirmed by Anyaduba, who notes, in 2006, that “the lukewarm and nonchalant attitude of most taxpayers towards voluntary compliance is widespread and pervasive”.[83]

The challenge presented by high costs of collection is also significant. There is no major empirical work that has directly measured the operating costs of the Nigerian tax system – compliance costs for taxpayers and administrative costs for the revenue authorities. But anecdotal evidence and evidence from other African developing nations suggests that the costs of collection will be high and represent a major challenge for the system. For example, Evans suggests that compliance costs in developing nations are typically four to five times higher than in developed countries.[84]

Other major challenges identified by Anyaduba also point to the sub-optimal administration and include:

One further challenge – and perhaps the largest – is

the size of the informal or shadow economy in Nigeria. Estimates

derived by

Schneider[85] suggest

that in 2002-03 Zimbabwe, Tanzania and Nigeria had by far the largest shadow

economies among African nations, as shown in

Table 2. Using a macro-economic

modeling approach based upon currency demand, Schneider estimated the size of

the Nigerian shadow

economy to be roughly 60% of GDP, compared to an African

unweighted average (based upon 37 countries) of just over 40%, and an average

in

21 developed OECD countries of 16%. Indeed, only a handful of central and South

American nations had higher shadow economies

than Nigeria. Although some

commentators suggest that analysing macro-economic data tends to overstate the

size of the shadow economy

(and therefore some prefer using surveys and tax

records),[86] there is

little doubt that the size of the shadow economy is one of the single most

important challenges facing the Nigerian tax

system.

Table 2 The Size of

the Shadow Economy in 37 African Countries

|

|

|

Shadow Economy (in % of official GDP) using the DYMMIC and

Currency Demand Method

|

||

|

No.

|

Country

|

1999/00

|

2001/02

|

2002/03

|

|

1

|

Algeria

|

34.1

|

35.0

|

35.6

|

|

2

|

Angola

|

43.2

|

44.1

|

45.2

|

|

3

|

Benin

|

47.3

|

48.2

|

49.1

|

|

4

|

Botswana

|

33.4

|

33.9

|

34.6

|

|

5

|

Burkina Faso

|

41.4

|

42.6

|

43.3

|

|

6

|

Burundi

|

36.9

|

37.6

|

38.7

|

|

7

|

Cameroon

|

32.8

|

33.7

|

34.9

|

|

8

|

Central African Republic

|

44.3

|

45.4

|

46.1

|

|

9

|

Chad

|

46.2

|

47.1

|

48.0

|

|

10

|

Congo, Dem. Rep.

|

48.0

|

48.8

|

49.7

|

|

11

|

Congo,

|

48.2

|

49.1

|

50.1

|

|

12

|

Cote d'Ivoire

|

43.2

|

44.3

|

45.2

|

|

13

|

Egypt, Arab Rep.

|

35.1

|

36.0

|

36.9

|

|

14

|

Ethiopia

|

40.3

|

41.4

|

42.1

|

|

15

|

Ghana

|

41.9

|

42.7

|

43.6

|

|

16

|

Guinea

|

39.6

|

40.8

|

41.3

|

|

17

|

Kenya

|

34.3

|

35.1

|

36.0

|

|

18

|

Lesotho

|

31.3

|

32.4

|

33.3

|

|

19

|

Madagascar

|

39.6

|

40.4

|

41.6

|

|

20

|

Malawi

|

40.3

|

41.2

|

42.1

|

|

21

|

Mali

|

42.3

|

43.9

|

44.7

|

|

22

|

Mauritania

|

36.1

|

37.2

|

38.0

|

|

23

|

Morocco

|

36.4

|

37.1

|

37.9

|

|

24

|

Mozambique

|

40.3

|

41.3

|

42.4

|

|

25

|

Namibia

|

31.4

|

32.6

|

33.4

|

|

26

|

Niger

|

41.9

|

42.6

|

43.8

|

|

27

|

Nigeria

|

57.9

|

58.6

|

59.4

|

|

28

|

Rwanda

|

40.3

|

41.4

|

42.2

|

|

29

|

Senegal

|

45.1

|

46.8

|

47.5

|

|

30

|

Sierra Leone

|

41.7

|

42.8

|

43.9

|

|

31

|

South Africa

|

28.4

|

29.1

|

29.5

|

|

32

|

Tanzania

|

58.3

|

59.4

|

60.2

|

|

33

|

Togo

|

35.1

|

39.2

|

40.4

|

|

34

|

Tunisia

|

38.4

|

39.1

|

39.9

|

|

35

|

Uganda

|

43.1

|

44.6

|

45.4

|

|

36

|

Zambia

|

48.9

|

49.7

|

50.8

|

|

37

|

Zimbabwe

|

59.4

|

61.0

|

63.2

|

|

Unweighted Average

|

41.3

|

42.3

|

43.2

|

|

Source: Schneider, F., 2004, “The Size of the Shadow Economies of 145 Countries all over the World: First Results over the Period 1999-2003”, Discussion Paper 1431, Institute for the Study of Labour, Bonn at p. 11.

4 STRATEGIES TO IMPROVE TAXPAYER COMPLIANCE

4.1 Underlying propositions

There are no quick fixes or “silver bullets” available to improve voluntary and enforced taxpayer compliance and the other challenges identified in the preceding section. Nor is there a “one size fits all solution”. Instead, what is required is a concerted, long-term coordinated and comprehensive plan that is tailored to the context and suitably resourced. This section details the processes involved in developing such a plan and the principal components of the plan.

The guidelines on managing and improving tax compliance released by the OECD in 2004 suggests that effective application of compliance strategies depend on a revenue authority being strong in “three key capabilities: resources, design and execution.”[87] Indeed, Bird and Gendron[88] identify adequate investment in tax administration as a critical ingredient for sustainable success in the reform of tax administration. The availability of resources to fund such investment is beyond the scope of this paper. But, for the purposes of developing appropriate compliance strategies, it is assumed that the resources can be found and allocated. There are, in any case, many indications that the revenue bodies (and their political masters) in Nigeria are more than aware of the strategic importance of providing adequate resources and developing those other capabilities.

What, then, can be done to improve tax compliance? In the first place, there are a series of key high level and strategic propositions that must underpin the development of appropriate compliance strategies at the operational level. These propositions have emerged from the paper to date, and are summarised for convenience here. Again, while they have been developed in the context of Nigeria, they would no doubt be of relevance to other developing countries.

Proposition 1: the legitimacy and credibility of the revenue authorities need to be established and enhanced as part of a broader consensual revenue-bargaining arrangement between government and its citizens.

This goes to the heart of good governance. Bird et al[89] conclude that a more legitimate and responsive state is likely to be an essential precondition for a more adequate level of tax effort in both developing countries and high income countries. This is also the key message from a number of other commentators, including Brautigam et al[90], who note that “...authority, effectiveness, accountability and responsiveness [are] closely related to the ways in which governments are financed. It matters that governments tax their citizens rather than live from oil revenues and foreign aid, and it mattes how they tax them. Taxation stimulates demand for representation, and an effective revenue authority is the central pillar of state capacity.”

Given that the overriding objective of the recently published National Tax Policy in Nigeria is “to provide a stable point of reference for all stakeholders in the country on which they shall be held accountable”[91], and that the document goes on to recognise the importance of the consensual relationship between the state and society in a number of reasoned ways, there is some cause for cautious optimism so far as this first proposition is concerned. However, there is much more to be done in order to ensure that “the attentions and political energies of a substantial fraction of [Nigerian] citizens in taxation issues [are engaged] by raising taxes from them. The felt experience of paying taxes should not be confined to small numbers of companies and very rich people”.[92] And those taxes need to be raised as consensually and as transparently as possible.

Proposition 2: the goals and objectives of tax reform need to be clearly articulated and the tax policy settings need to match those goals.

It may be obvious that “good tax policy influences economic development”[93], but that does not detract from the importance of the statement. Having a clear vision of where the tax reform is supposed to lead and then getting the tax policy settings right is absolutely critical to the success of tax reform, and a precondition for enhanced compliance activity. Within these parameters, Nigerian tax reform appears to be headed in the right direction.

The objectives of the reform are clearly stated in the National Tax Policy[94], and the policy settings appear capable of achieving those goals and are in line with mainstream thinking on the point. They involve, sensibly, a broad simplification of the tax system incorporating simpler taxes, policies and processes. The National Tax Policy anticipates fewer taxes; the use of broad based taxes with lower rates; a shift in emphasis from direct taxes to indirect taxes; a reduction in the number of tax incentives and tax expenditures; the elimination of multiple taxation by various tiers of government; and consolidation and centralisation of political and administrative responsibility for taxes and the administration of the tax system.

Proposition 3: A risk management approach to taxpayer compliance is vital and should in turn underpin resource allocation decisions.

Resources are not infinite and therefore risks to the revenue need to be prioritised and continually reassessed. Adopting a risk management approach means that the revenue authorities need to understand their taxpayers and create appropriate typologies. Different strategies are needed to address different types of compliance behaviour, and a variety of audit strategies will need to be developed according to risk assessment and resource availability. There is a need for on-going research to understand taxpayer morale and to monitor the impact of the various strategies that are employed. All of this has implications for the introduction of appropriate management information systems and infrastructure within the revenue authorities.

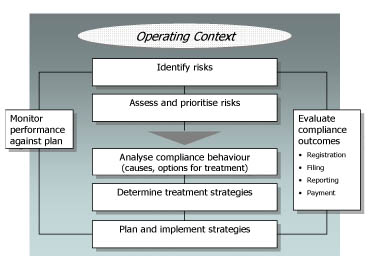

The Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (“OECD”) has suggested a broad compliance risk management process designed to identify, assess, prioritise and treat compliance risks, and this is summarised in Figure 2.[95] Although informed primarily by the experiences of more developed economies, the process is also appropriate for less developed jurisdictions.

Figure 2: The OECD Compliance risk management process

Source: OECD, 2008, Monitoring

Taxpayers’ Compliance: A Practical Guide Based on Revenue Body Experience,

OECD, Paris, p. 8.

4.2 Compliance strategies

Based on these three propositions, the following, more specific, compliance strategies can begin to address the needs of the Nigerian revenue authorities at the operational level and allow them to move away from their current sub-optimal performance levels. The strategies are grouped into four broad categories: creating a more effective tax administration; fostering voluntary compliance and enhancing taxpayer morale; strengthening and enforcing compliance; and tackling the shadow economy. Note that in practice the categories and strategies are not as discrete or compartmentalised as suggested in the paper – they are of necessity interdependent, with all feeding into each other and off each other.

4.2.1 Creating a more effective tax administration

An effective tax administration is obviously critical to enhanced compliance outcomes in the four key areas of service, education, verification and enforcement. Without this vital ingredient the major compliance risks relating to taxpayer notification and registration, return filing, correct reporting and accurate and timely tax payment cannot be overcome. There are a number of possible strategies that can help to achieve a more effective tax administration, including strategies related to: organisational and institutional reform; management strengthening; nuts and bolts reform; and building integrity and tackling corruption.

Organisational and institutional reforms

Autonomous

revenue authorities

In recent years many developing countries have

established their tax departments into autonomous or semi-autonomous revenue

authorities

(“ARAs”). It has been a noticeable world-wide trend,

with some suggestions that the World Bank has, upon occasions,

“been a

persuasive

salesman”.[96]

As of March 2006 Fjeldstad and Moore note that there were about 30 ARAs in the

developing world, largely in Africa and South America

and including Uganda

(1991), Kenya (1995), South Africa (1997), Ethiopia (2002) and Gambia

(2005).

The defining feature of an ARA is some degree of autonomy whereby the revenue collection function is removed, either partly or wholly, from the Ministry of Finance. The management of the ARA therefore has significant independence in financial, personnel and operational matters, but is accountable for delivering agreed results, with continuation of appointment and renewal of contract for top management dependent upon revenue administration performance.[97] These independent revenue agencies, it is argued, are thus more able to provide better pay and other incentives to their staff while also imposing greater accountability for performance.[98] Taliercio argues that if one compares the pre- and post- reform state of affairs in countries where ARAs have been introduced, there is improvement in most cases along most dimensions of performance. Moreover, he suggests, the relatively more autonomous revenue authorities (such as Peru, Kenya and South Africa) have been more adept at increasing performance than the less autonomous ones (such as Uganda, Mexico and Venezuela).[99]

Others are more circumspect. Gallagher notes that the jury is still out,[100] while Fjeldstad and Moore suggest that many of the perceived advantages may have been short term and identify a number of conceptual and practical problems with ARAs that suggest they are not always the panacea that the World Bank may have suggested.[101]

Arguments for and against adopting an ARA strategy are ultimately beyond the scope of this paper. It is noted, however, that despite initial resistance, Nigeria appears to be developing its revenue agencies along autonomous lines, both in terms of its funding structure and in terms of its separation from the broader civil service set up.[102]

Organisational options

Regardless of whether the revenue authority

is constituted as an autonomous or semi-autonomous body, the way in which it is

internally

organised can have a significant impact upon the effectiveness of the

tax administration. “A well-designed organizational

structure can provide

a foundation for effective tax administration, which minimizes tax evasion

opportunities and fosters voluntary

compliance”.[103]

Traditionally three separate models for the organisation of revenue authorities have been suggested both in the broader organisational theory literature[104] and in more specific literature relating to tax administration:[105]

Sometimes, revenue agencies adopt a fourth approach, involving some combination of these three models, often referred to as a matrix approach.

There are obvious advantages and disadvantages of each of the three principal approaches, as summarised in Table 3.

Table 3 Summary of advantages of different organisational models

|

Criterion

(Advantage) |

Organisational model

|

||

|

Product-based/

type of tax |

Functional

|

Client-based/

Type of taxpayer |

|

|

Establishes clear accountability within organisation and control for each

tax

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

|

Improves opportunity for compliance by taxpayers

|

Neutral

|

Yes

|

Neutral

|

|

Enhances quality of taxpayer service

|

Yes

|

No

|

Yes

|

|

Permits different administrative procedures for different taxes

|

Yes

|

No

|

No

|

|

Produces lower administrative costs and high staff productivity (less

duplication)

|

No

|

Yes

|

No

|

|

Imposes lower compliance costs on taxpayers

|

No

|

No

|

Yes

|

|

Reduces opportunities for collusion and corruption

|

No

|

Yes

|

No

|

Based upon Vehorn, C. and J. Brondolo, 1999, ‘Organizational Options for Tax Administration’, paper presented at 1999 Institute of Public Finance Conference, Zagreb, June.

Developing countries have tended to move away from product-based structures built upon different types of tax to those which are based upon function, although often with elements of a client-based market segmentation approach also in evidence (for example, the introduction of large taxpayers units focusing upon the large companies which are often responsible for a disproportionate amount of revenue collections; or the introduction of industry-based organisational structures).[106] In this way they have been able to secure the advantages of improved accountability and control, enhanced compliance, better administrative efficiency, reduced corruption and more customised taxpayer service.

Management strengthening:

Gill has noted that

“[t]he quality and continuity of leadership of the [revenue administration] reform effort is a major determinant of success. Senior managers should be selected carefully.... Efforts should be made to minimize changes as these have a disruptive effort on the reform process”.[107]

Those senior managers carry the main burden of “setting strategic goals; formulating operational policy; managing financial, human, information and physical resources effectively; supervising, monitoring and evaluating performance; improving coordination, anticipating and resolving operational problems; enforcing internal control systems; preventing corruption; improving mechanisms to redress taxpayer grievances; and interacting with external stake-holders”.[108]

Unfortunately the importance of a strong and continuing management team – often necessarily supported by political champions and mentors – has been under-emphasised in many countries, with the result that weak management teams and perverse management practices have been allowed to continue to the detriment of the development of a changed culture.

Nuts and bolts reform

In addition to the need for

organisational change and management strengthening, there are many other more

mundane, but nevertheless

vital, changes that can help to create a more

effective and efficient tax administration, thereby enhancing the revenue

authority’s

capacity to enhance voluntary compliance and strengthening its

ability to enforce compliance. These “nuts and bolts”

reforms

include strategies relating to areas such as registration and tax collection

Registration

Many developing countries (and most developed) have

introduced unique Taxpayer Identification Numbers (“TINs”) as a

means

of ensuring registration by taxpaying units (whether individuals or

corporates). This is a strategy facilitated by the development

and spread of

digitalisation and communication

technologies.[109]

The existence of a TIN “forms the basic building block for revenue

administration IT systems, as it allows connecting taxpayers

to their returns,

payments and major taxable transactions with third

parties”.[110]

Field surveys to detect unregistered taxpayers, as well as extensive publicity

campaigns, have often accompanied the introduction

of TINs.

Tax collection

Improved information technology has enabled Nigeria

to consider a number of potential strategies for enhancing the efficiency and

integrity of revenue collections. For example, in 2004 the Bank Collection

Reform Committee (with representatives from FIRS, the

Central Bank of Nigeria,

the Nigerian Customs Service, Telnet (Nigeria) Ltd and the four leading Nigerian

banks) was set up to consider

means through which an improved tax collection

system devoid of leakage and fraud could be established in

Nigeria.[111] Its

“Project

FACT[112] is well

advanced, and automated accounting systems and an integrated tax administration

system are apparently currently being developed

and implemented.

Building integrity and tackling corruption

The integrity of

its staff and systems is a vital component of any effective revenue

administration, and yet – as Bahl and Bird

point out – corruption

and taxation have always been associated in history – and not just in

developing

countries.[113] It

would be naïve to believe that corruption is not a serious issue in Nigeria

– indeed Uche and Ugwoke noted in 2003

that “[t]he major threat to

the effective administration of VAT in Nigeria...is the widespread corruption

and indiscipline

which are deeply entrenched in all aspects of the

country’s social and economic

life”.[114]

Corruption may be systematic – involving groups of employees acting together in a corrupt fashion and often led by senior staff – or individual; and may or may not involve external “clients”. Examples are not difficult to cite: charging for services that should be free; diverting cash; making false repayment claims; losing files; and receiving payments to complete tax returns or bribes to favorably settle audits. And corruption is not limited simply to tax activities – it can also include abuses of power such as theft or private use of goods like office equipment; fraudulent subsistence and travel allowance claims; and stealing time to pursue outside interests and/or employment.[115]

The consequences of corruption are obvious. It is a cancer that destroys the organisation itself and undermines all other aspects of society. It erodes confidence in the tax system and encourages evasion. It increases the costs of doing business and distorts the level playing field that should be available. And to the extent that there is a political limit as to the amount of tax that people will bear in a developing country (and that there is therefore a substitution effect between taxation and corruption), it reduces the amount of formal tax that can be collected.[116]

A number of strategies to combat or address the issues of corruption in a revenue authority have been identified in the literature.[117] These include:

Corruption risk mapping

The preparation of “Corruption Risk

Maps”, designed to guide procedural changes to reduce opportunities of

corruption,

is a useful starting point for any revenue agency determined to

tackle problems of corruption. In Columbia this strategy was successfully

employed, based upon an initial systematic study of important business

processes, to address the vulnerable points in the systems

and identify optimal

strategies for dealing with

each.[118]

Recruitment policies and practices

Staff need to be carefully

recruited on merit based selection principles, and remunerated at levels which

are at least comparable

to equivalent positions in banking and the accounting

profession, have access to carefully developed in-house and external training

possibilities and have realistic opportunities for career and income

progression.

Ethical policies and practices

Staff must be aware of the

importance of integrity at both the personal and organisational levels, and

policy and practice must reflect

this. It is not sufficient merely to introduce

ethical “Codes of Conduct”, sets of internal disciplinary rules and

instruments

such as “Taxpayers’ Charters”; they also need to

be shown to be “living” documents that inform everyday

activity and

decision-making. Other practical measures include asset declarations for all

staff, and the availability of avenues

for whistle blowing (including protection

from disclosure after the event). Collier et al, in an Indonesian context,

identified

that the establishment of peer learning groups in the workplace

considerably enhanced and reinforced ethical behavior and reduced

corruption in

a revenue authority when allied to internal training on the topic. The groups

comprised a small number of trainees

who maintained contact and reinforced

communities of ethical practice in a variety of ways, including face to face

meetings, and

SMS and email groups, during and after the delivery of the

training.[119]

Internal controls and deterrence

Strong internal controls are an

essential part of any strategy designed to address corruption in a revenue

authority. Child notes

that managers must be proactive and conduct desk and

office inspections, and design procedures and systems that deter integrity

lapses

and make them easier to

spot.[120] Other

examples include restricting access by taxpayers to designated taxpayer service

areas so that they cannot access other revenue

authority work spaces;

restricting access by employees to scanned copies of original records to prevent

tampering; creating audit

trails of administrative decisions and changes made to

taxpayer current accounts; and separating the functions of assessing and

collection

in order to reduce opportunities for corruption and

collusion.[121]

In addition, an effective internal investigation force, combined with severe penalties (including dismissal and prosecution) for malfeasance and a strong likelihood of detection, will inevitably reduce the incidence of corruption. “To the extent corruption follows an economic calculus, the expected value of the outcome of taking a bribe may be heavily influenced by the chances of getting caught and being heavily penalized”.[122]

Statutory changes

Statutory changes to increase transparency,

remove discretion and simplify the law can make a significant contribution to

the enhancement

of the integrity of the operation of the revenue authority.

Where the structure of a particular tax is as transparent as possible,

and

obligations and liabilities are clearly stated, taxpayers will be less likely to

be cheated. Bahl and Bird note that “[n]othing

good can come of a

situation in which tax administrators and tax payers negotiate over how large

the tax liability should be. One

problem in the practice of income taxation in

developing countries is that, apart from withheld taxes, tax liabilities are, in

fact,

often

negotiated”.[123]

Minimise taxpayer/revenue agency interaction

The higher the level

of contact and interaction between tax officials and taxpayers, the greater the

scope for corruption and collusion.

Therefore minimising that contact through

the use of self-assessment, withholding taxes and the like can be an effective

strategy.

Gill identifies examples from Latvia and Russia where work processes

were modified to reduce interaction between tax officials and

taxpayers[124], and

Bahl and Bird note that VAT and payroll taxes tend to score relatively high in

this

respect.[125]

Reduce compliance costs

Compliance costs for taxpayers in

developing countries are four to five times higher than those in developed

countries.[126]

This therefore suggests that reducing compliance costs “lowers the amount

of bribe a (rational) taxpayer might be willing

to pay to avoid the declaration

and payment

process”.[127]

One strategy that does not appear to have been successful in combating corruption is the privatisation or outsourcing of the tax collection function. Tax farming (the process where the right to collect tax is auctioned off to a private agent in exchange for a fixed sum payable in advance) and tax sharing (whereby private agents collect taxes, with the right to keep a share of the total collection) have often been introduced with the objective of reducing administrative costs and increasing the level and reliability of collections.[128] The examples of outsourcing of some local authority tax collection in Tanzania and Uganda suggest that they may sometimes have succeeded in increasing revenue collections, but that the levels of corruption have also increased.[129]

4.2.3 Fostering voluntary compliance

In 2004 the OECD suggested that “[c]ompliance is most likely to be optimised when a revenue authority pursues a citizen-inclusive approach to compliance through policies that encourage dialogue and persuasion, combined with an effective mix of incentives and sanctions”.[130] This section of the paper focuses upon the voluntary aspects of this broad compliance strategy, while Section 4.2.3 turns to the sanction-based enforced elements.

Gill notes that voluntary tax compliance does not have a long history in many developing countries.[131] Nonetheless, this has been an area where significant developments have taken place in recent years. There has been a “very substantial shift in the attitudes of tax administrations towards taxpayers”.[132] Based in large part on the literature on compliance explored in Section 2 of this paper, tax administrations have come to recognise that that a cooperative and positive engagement with taxpayers and their advisers in a customer-service focused and user-friendly environment will be more productive and efficient than more traditional adversarial and antagonistic approaches.

As a result, the strategies designed to foster voluntary compliance have taken two broad and mutually supportive directions: building positive taxpayer and tax community morale; and making compliance easier and cheaper for taxpayers.

Building positive taxpayer and tax community morale

Enhanced

compliance, the literature tells us, is likely to occur where fiscal ignorance

is tackled and reduced, where taxpayers feel

that they are getting a fair deal

from the exchange relationship with the state, where the environment is

cooperative and where positive

attitudes towards taxation are nourished.

Taxpayers, and potential taxpayers, need to be aware of the general concept of

taxation

and why they should pay taxes.

Based upon this analysis, revenue authorities in many countries have undertaken community awareness campaigns. Some revenue authorities have been very creative in raising awareness of the value of the social exchange and contract between taxpayer and state, using TV skits; radio programs; competitions to create advertisements displayed on buses; school plays on tax issues; fairy tales spun around tax compliance; and the incorporation of tax themes in school curricula, in collaboration with Ministries of Education.[133] The South African Revenue Service widely advertises that “your taxes paid for this road/school/hospital”[134] while the Australian Taxation Office (“ATO”) used, for a long time, the slogan “Building a Better Australia”.

The focus is not just on the relationship between the tax authority and the taxpayer. The relationship between the tax authority and tax practitioners, industry associations, trade unions and other community groups can be just as important. The OECD recognises, correctly, the importance of building community partnerships, and that “[a]lliances with trusted intermediaries may be crucial to challenging community or industry attitudes and influencing taxpayer behaviour. Network alliances allow for the development of an integrated approach to addressing compliance issues and mutual support which greatly increase the chances of success of any given strategy”.[135]

Making it easer and cheaper to comply

On the assumption that

many, if not most, taxpayers wish to comply with their tax obligations (within

cultural and social norms),

efforts are being made in many revenue authorities

to make it easier and cheaper for taxpayers to comply. The strategies that can