University of New South Wales Faculty of Law Research Series

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

University of New South Wales Faculty of Law Research Series |

|

Last Updated: 4 September 2008

Crime, Justice and Indigenous People

Chris Cunneen

In: Barclay, E., Donnermeyer, J., Scott, J. and R. Hogg (eds) Crime in Rural Australia, The Federation Press, Leichhardt, pp142-153,

Abstract

Indigenous people are proportionately more likely to live in rural and remote areas of Australia than other culturally and linguistically distinct groups. For this reason, a study of rural crime and justice demands particular attention be paid to the nature and incidence of crime in Indigenous communities as well as the relationship between Indigenous people and the broader non-Indigenous justice institutions.

This chapter considers three issues: the nature of crime and victimisation in Indigenous rural and remote communities; the responses of the Anglo-Australian criminal justice system to Indigenous crime and justice issues; and the potential for developing and strengthening Indigenous responses to crime. In brief, the rural and remote nature of Indigenous communities influences the social and spatial dynamics of crime. Further, government responses have varied depending on the nature of the Indigenous and non-Indigenous community. In many respects remote Indigenous communities have tended to have less consistent intervention by justice and welfare agencies, while ‘mixed’ rural communities where Indigenous people comprise a significant minority have tended to have a much stronger law and order presence aimed at controlling Indigenous populations. A further dynamic has been recent work in Indigenous communities aimed at developing localised governance structures to enable communities to deal more effectively with crime prevention and more effective models of sanctioning and rehabilitation (often drawing on various alternatives seen to be more appropriate for Indigenous control).

Introduction

Indigenous people are proportionately more likely to live in rural and remote areas of Australia than other culturally and linguistically distinct groups. For this reason, a study of rural crime and justice demands particular attention be paid to the nature and incidence of crime in Indigenous communities as well as the relationship between Indigenous people and the broader non-Indigenous justice institutions.

This chapter considers three issues: the nature of crime and victimisation in Indigenous rural and remote communities; the responses of the Anglo-Australian criminal justice system to Indigenous crime and justice issues; and the potential for developing and strengthening Indigenous responses to crime. In brief, the rural and remote nature of Indigenous communities influences the social and spatial dynamics of crime. Further, government responses have varied depending on the nature of the Indigenous and non-Indigenous community. In many respects remote Indigenous communities have tended to have less consistent intervention by justice and welfare agencies, while ‘mixed’ rural communities where Indigenous people comprise a significant minority have tended to have a much stronger law and order presence aimed at controlling Indigenous populations. A further dynamic has been recent work in Indigenous communities aimed at developing localised governance structures to enable communities to deal more effectively with crime prevention and more effective models of sanctioning and rehabilitation (often drawing on various alternatives seen to be more appropriate for Indigenous control).

Before I explore these issues more fully, it is worth noting the structure, location and socio-economic profile of Indigenous peoples in Australia, and the impact that these factors are likely to have on matters of crime and justice. Some 27 per cent of the Indigenous population nationally live in remote or very remote areas compared to 2 per cent of the non-Indigenous population. Conversely, 30 per cent of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people live in major cities, compared to 67 per cent of the non-Indigenous population. The remainder of Indigenous people (43 per cent) live in rural and regional areas (ABS 2003). [1]

One of the key characteristics of the Indigenous population in Australia is its youthfulness. In 2001, the proportion of Indigenous people under 15 years of age was 39 per cent compared with 20 per cent of non-Indigenous people. Persons aged 65 years and over comprised 3 per cent of the Indigenous population and 13 per cent of the non-Indigenous population (ABS 2004a). Australia's Indigenous population had a median age of 20 years, some 16 years younger than the median age for the non-Indigenous population (ABS 2004a). The relative youthfulness of Indigenous people in Australia is important because we know that reported crime is likely to involve younger people in their late teenage / early adults years.

In terms of education, Indigenous young people are less likely to complete Year 12 than non-Indigenous young people (18 per cent compared to 41 per cent). The situation is exacerbated by geographic remoteness, where the rate of completion of Year 12 was only a quarter of the non-Indigenous rate (ABS 2003).

In terms of employment, Indigenous persons in the labour force were almost three times more likely than non-Indigenous persons to be unemployed (20 per cent compared with 7 per cent ). While Indigenous unemployment in remote areas appears lower than other regional and urban centres, this is largely an artefact of the Community Development Employment Program (CDEP or work-for-the-dole scheme). Some 79 per cent of CDEP workers are in remote areas (ABS 2003). In 2001, the average household income for Indigenous persons was $364 per week, or 62 per cent of the corresponding income for non-Indigenous persons ($585 per week). For Indigenous persons, income levels generally declined with increasing geographic remoteness (ABS 2003).

In terms of households and overcrowding, average Indigenous households are larger than their non-Indigenous counterparts. Of more relevance to the current discussion, however is the fact that one in four Indigenous people over the age of 15 years live in over-crowded housing and the situation is worse in remote areas (SCRGSP 2005: 10.11). Some remote/rural communities like Palm Island report housing overcrowding at 17 people per house (Waters 2005). Overcrowding in housing can be associated with a range of social problems including family violence.

Finally, it is worth noting that poor health is also a major factor in Indigenous communities. Some poor health outcomes, including the higher prevalence of certain diseases, arise from inadequate housing and poor basic facilities (SCRGSP 2005: 10.3). Alcohol consumption is also problematic for some Indigenous people. In remote communities, a higher proportion of Indigenous people do not consume alcohol (46 per cent), than other non-remote Indigenous people (25 per cent) or non-Indigenous people more generally (16 per cent). However, in remote areas there is also a comparatively large group who drink in the medium to high risk category. Excessive alcohol consumption is associated with a range of health problems, and, importantly in the current discussion, inter-personal violence. We know for example, that alcohol is more likely to be involved in Indigenous homicides compared to non-Indigenous (SCRGSP 2005: 3.71).

The nature of crime and victimisation in Indigenous rural and remote communities

Thus if we were to generalise concerning Indigenous

people in Australia the population is younger, living out of cities in rural and

remote areas, and experiencing significant levels of disadvantage across a range

of social, economic and health indicators. Again,

in general, those measures of

poverty are exacerbated the more remote the community. Counterpoised against

this are elements of cultural

strength.

In 2002, the National Aboriginal and

Torres Strait Islanders Social Survey found that measures of cultural

attachment were reported

at much higher rates in remote areas. In remote areas

38 per cent of Indigenous people were living on their homelands, 87 per cent

had

attended a cultural event in the last 12 months, and 54 per cent spoke an

Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander language (ABS

2004b).

It is important to recognise that the social, economic and spatial location of Indigenous people in Australia today is an outcome of a complex historical process deriving from two centuries of colonisation. In general terms Indigenous peoples living in remote communities have been affected by colonisation far more recently than Indigenous peoples of south eastern mainland Australia, Tasmania and the south west of Western Australia.

Indigenous people living in regional and country towns of Australia have experienced their own set of issues. Historically, people may have been forcibly relocated to missions and reserves on the outskirts of country towns. Today, people live on this land which is now controlled under Aboriginal land rights legislation, but is still colloquially known as the ‘mission’ or ‘reserve’ (for example, Moree or Walgett in NSW). Alternatively, a system of town camps may have emerged, as for example has occurred in Alice Springs. These towns camps have both permanent residents and transient people moving in from remote communities, often to access services. In addition, many country towns have Aboriginal people living in particular defined areas because of the location of public housing.

Urban Indigenous populations also vary - for example small residual populations of Indigenous people have remained in the heartland of Australian cities such as La Perouse and Redfern in Sydney, while new urban and semi-urban populations have grown with public housing relocations after the 1970s and 1980s. So, for example, in contemporary Sydney the largest Indigenous population is in the western suburbs - a relatively recent population which has moved from other urban and rural locations. A further factor cutting across these divisions is the high mobility of Indigenous people between different communities. Individuals may spend time with extended family in both urban and rural locations, and frequently move between the two.

What this leads to is a kind of geographic mosaic of differing levels and types of contact with the criminal justice system. For example, contact with criminal justice agencies (as measured by police contact) is slightly less in remote areas than non-remote (ABS 2004b). However, some remote areas have very public and volatile relations with police. For example, Palm Island residents burnt a police station to the ground after a death in custody in 2004.

Indigenous people are over-represented before the courts and in prison for most offence categories, although there are variations. For example, Indigenous people are much less over-represented for offences relating to fraud, traffic-related matters and illicit drugs. Generally, Indigenous people come before the courts for more serious property offences including break and entering, and stealing motor vehicles, whereas non-Indigenous people have a greater proportion of more minor property offences such as shoplifting and larceny. Another area of significant difference is the large proportion of Indigenous people who come before the courts on matters of violence. Research in various jurisdictions has noted that the level of over-representation is among the greatest for these category of offences (Fitzgerald and Weatherburn 2001, Harding et al 1995, Cunneen 2005). I return to this issue below.

There are also significant differences between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people in relation to court appearances for public order offences. In New South Wales, Indigenous young people appeared in court at more than ten times the rate of non-Indigenous youth for these offences (Luke and Cunneen 1995: 11). In the Northern Territory, 72 per cent of court appearances for public order offences involved Indigenous people (Luke and Cunneen 1998:33). Information on police arrests also shows the prevalence of public order offences. In Western Australia, 45 per cent of all arrests for public order offences involved Indigenous people. This was the offence category with the largest proportion of Aboriginal people (Harding et al 1995: 43). Recent research in Queensland shows that 30 per cent of all Indigenous adult local court appearances were for public order-related offences compared to 12 per cent of non-Indigenous appearances (Cunneen 2005:55).

Finally, Indigenous people are more highly over-represented in their appearances before the courts for those group of offences called ‘justice-related’ matters. These offences are primarily related to breaches of existing court orders such as conditions placed on bail, bonds, probation or parole.

Poverty, Crime and Rural Areas

In general it is towns camps, ex missions and reserves, and public housing estates in rural towns that are most associated publicly with crime and disorder involving Indigenous people. For example, recent reports stated that Alice Spring’s town camps had experienced 15 murders and homicides in the space of 16 months (‘Politicians Quiet on Town Camp Unrest’, ABC News Online 11/4/06). Similarly, the Gordon public housing estate in Dubbo is often in the limelight because of crime and public disorder. In January 2006 it became subject to a police ‘lockdown’ which utilised new public order legislation introduced after the Cronulla riots. Reported crime statistics often find the highest rates of interpersonal violence and house burglary in rural communities where there are significant Indigenous populations. For example, in 2005 the highest reported rates of assault were in north western and far western divisions of NSW. Rates of house burglary were the second and third highest in the State in the same divisions (Moffat et al 2006: 6-9).

There may also be a relatively close fit between Indigenous levels of poverty, crime and victimisation. For example, New South Wales is divided into six regions for federal and state Indigenous matters (arising from the old ATSIC regions). They are Sydney, Binaal Billa (Wagga Wagga and the southwest), Kamiliaroi (Tamworth and the north), Murdi Paaki (Bourke and the northwest and west), Many Rivers (Coffs Harbour and the north coast) and Queanbeyan (the southeast). The Murdi Paaki region is the most disadvantaged Indigenous region in New South Wales and among the most disadvantaged nationally (ABS 2000). The Murdi Paaki region has much higher offending levels for Indigenous people as measured by local court appearances, with a rate almost twice that of Indigenous people in the Sydney region (Cunneen 2002: 17). Similarly, victimisation rates for Indigenous people in the Murdi Paaki region are much higher than for Indigenous people living elsewhere in New South Wales. The victimisation rate per 1000 of Indigenous population living in Murdi Paaki was 255 compared 42 in Sydney and 45 in Queanbeyan. Thus an Indigenous person in Bourke is around six times more likely to be a victim of crime than an Indigenous person living in Sydney (Cunneen 2002: 31).

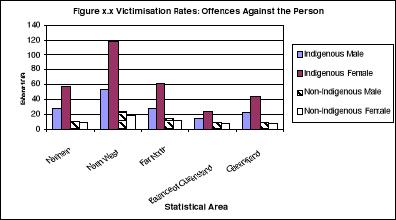

A regional analysis of poverty, disadvantage and victimisation in Queensland confirms the links identified above. The study shows that the far north and north west regions of Queensland have the worst measures of low income, high unemployment and housing overcrowding for Indigenous people (Cunneen 2005:11-13). Victimisation data for offences against the person supplied by the Queensland Police show whether the victim was male or female and Indigenous or non-Indigenous, and are shown in Figure X.X.

Overall, the victimisation levels are approximately four times higher for offences against the person among Indigenous compared to non-Indigenous peoples. The rate of victimisation is particularly high in the north west region where it is 2.6 times higher than the Indigenous rate for Queensland as a whole (86.6 compared to 33.5 per 1,000). Generally the northern and far north regions have higher rates than the rest of the State.

We can see clearly from this evidence that offending and victimisation among Indigenous people are not equally distributed across the population. The data from Queensland and NSW both show that Indigenous people in particular rural areas are over-represented as both victims and offenders, and these areas are the ones that exhibit highest levels of poverty.

Indigenous Women and Violence

The rate at which Indigenous women are victims of crimes against the person is also shown in the above Figure x.x. For Queensland as a whole, Indigenous women are twice as likely as Indigenous men to be victims of offences against the person. They are 4.7 times more likely to be victims compared to non-Indigenous men, and nearly six times more likely to be victims than non-Indigenous women. In the north west region, the rate of victimisation for Indigenous women is 118.4 per 1,000 of the Indigenous female population (Cunneen 2005:33-34). Extrapolating from the homicide data, we know that this violence is more likely to take place in the family environment, and between intimate partners or other family members (SCRGSP 2005: 3.71).

A nine year study of homicide and Indigenous women between 1989 and 1998 showed that the rate of homicide for Indigenous women was 11.7 compared to a non-Indigenous rate of 1.1. Thus Indigenous women were more than 10 times more likely to be a victim of homicide than other women in Australia (Mouzos 1999). Indigenous women were also more likely to be killed by an intimate partner than non-Indigenous women (75 per cent for Indigenous women compared to 54 per cent for non-Indigenous women). Conversely, very few Indigenous women were killed by strangers (1.5 per cent of Indigenous women compared to 17.2 per cent of non-Indigenous women) (Mouzos 1999). Approximately 95 per cent of Indigenous women killed were killed by Indigenous men (Mouzos 1999).

Research in New South Wales shows that Aboriginal women are between 2.2 and 6.6 times more likely to be victims of crime than other women. Rates of sexual assault for Aboriginal women were 251.7 per 100,000 compared to 101.4 for women generally (Fitzgerald and Weatherburn 2001).

Under-reporting of violence against Aboriginal women appears to be a significant problem, with Aboriginal women less likely to report than non-Aboriginal women (Harding et al, 1995:18, Memmot et al 2001:7). Numerous reports have considered the issue of why Aboriginal women are less likely to report offences to police (see, for example, Criminal Justice Commission 1996, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Women’s Task Force on Violence 2000).

The relationship between Aboriginal women and violence also highlights how the separation between ‘victim’ and ‘offender’ is not at all clear. In reality many Aboriginal people in the criminal justice system are both offenders and victims. For example, some 78% of Aboriginal women in prison in New South Wales have been victims of violence as adults. More than four in ten Aboriginal women in prison reported being victims of a sexual assault as an adult (44%) (Lawrie 2002:41). Other research shows that being a victim of assault or abuse is also strongly associated with the likelihood of arrest for Aboriginal people (Hunter 2001). A further point to be made in the context of the current discussion is that these patterns of victimisation are likely to be concentrated in particular areas where poverty is highest and the opportunity to access services is lowest. Thus Indigenous women in north west Queensland have a much greater likelihood of being a victim of violent crime than Indigenous women elsewhere in the State.

Understanding Indigenous Over-Representation in the Criminal Justice System

It is been recognised for some time that there is a need for a multifaceted understanding of why Indigenous people are over-represented as victims and offenders in the criminal justice system. An adequate explanatory model involves analysing interconnecting issues which include historical and structural conditions of colonisation, social and economic marginalisation, and systemic racism, while at the same time considering the impact of specific (and sometimes quite localised) practices of criminal justice and related agencies (Cunneen 2001).

Some important and specific factors necessary to explain Indigenous over-representation include:

It is can be seen from the list that rural issues are important across a range of factors, including the concentration of poverty in particular areas, and the lack of access to services. In addition, specific elements of the criminal justice system may not operate in rural areas, such as the availability of non-custodial sentencing options – a point I return to below.

Responses of the Anglo-Australian criminal justice system.

Reponses to Indigenous people by the criminal justice system have varied during different historical periods. Very broadly, it is possible to distinguish three periods as (i) dispossession and war during the late 18th and 19th centuries; (ii) protection and segregation during the late 19th and early 20th centuries; and (iii) formal equality since the 1960s. Policing and criminal justice system responses to Indigenous people varied considerably across different periods and locations. The processes of colonisation were not uniform across time and space, and as result the time of contact varied. It is not possible to review these issues here and they have been dealt with in more detail elsewhere (Cunneen 2001, Hogg 2001).

The most important events distinguishing the recent period of contact with the criminal justice system was the demise of formal protection and segregation regimes and the movement of some Aboriginal people off former reserves and missions and into urban and rural centres. Corresponding with this change was the development of a perception that Indigenous people constituted a specific crime and disorder problem which demanded increased police attention and subsequent criminalisation. Aboriginal – police relations became highly problematic, particularly in rural towns and cities like Bourke, Brewarrina, Roebourne, Geraldton, and Townsville, and a few urban centres in capital cities such as Redfern, Fitzroy, and Musgrave Park. Particular rural and city areas became associated with ‘over-policing’ of Indigenous people which was reflected in the much stronger law and order presence aimed at controlling Indigenous populations. In the contemporary period the nadir of Aboriginal – police relations was reached at the time of the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody (RCADIC) (1987-1991). Some two thirds of the deaths investigated by the Commission had occurred in police custody.

Since the RCADIC, relations between Indigenous people and criminal justice agencies have tended to be more complex. On the one hand levels of criminalisation, particularly as measured by imprisonment have grown apace. On the other hand government agencies publicly advocate a commitment to reducing Indigenous over-representation in the criminal justice system and pay at least some attention to Indigenous demands for self-determination.

A recent example of the criminalisation approach is shown in the development of alcohol management plans in Indigenous communities in Queensland which includes restricted areas for alcohol. When a ‘restricted area’ is declared by law, a limit is set on the type and quantity of liquor that can be carried within the area. A person breaching the legislation can be fined or imprisoned. For a third offence this can amount to a $75,000 fine or 18 months imprisonment. Since the legislation has been put in place assaults have decreased, but there has also been a 414% increase in liquor offences (Cunneen 2005:156). As one magistrate put it,

I have not seen any of the sly groggers that are supposed to be rampant... The people who generally front up [to court] are either poor old drunks, or people bringing a bit of grog home from shopping (cited in Cunneen 2005:158).

What makes the issue particularly concerning is the fact that these specific restrictions only apply in Indigenous communities in Queensland.

General increases in police powers over recent years have also impacted negatively on Indigenous people. For example, the Police and Public Safety Act 1998 in NSW gives police specific ‘move on’ powers and the power to search people suspected of being in possession of knives and other prohibited implements (such as scissors, nail files, and so on). One aspect of the enforcement of the legislation is the way that it has impacted on young people, and more specifically Aboriginal young people. The legislation has general applicability to adults and juveniles. However it is overwhelmingly enforced against young people. Some 48% of people given directions to move-on were aged 17 years or younger. If we look more closely at the use of this legislation then it is also clear that not all young people are equally affected by it. In general, towns with high Aboriginal populations had much higher use of searches and move-on directions. Move-on directions were used by police some 184 times more frequently per head of population in Bourke and Brewarrina than they were in Sydney’s Rose Bay (NSW Office of the Ombudsman 2000:233-4). Similar disparities are also evident with the use of searches.

A key factor affecting the relationship of Indigenous people with the criminal justice system in regional, rural and remote areas is access to services. The New South Wales Legislative Council Standing Committee on Law and Justice (2006) recently completed an inquiry into community-based sentencing options in rural and remote areas. The focus of the inquiry was the extent to which options which the courts can use when sentencing offenders are actually available in rural and remote areas. The Committee found that supervised bonds, community service orders, periodic detention and home detention were not available in many parts of New South Wales. For example, home detention has been operating for nearly 15 years, but is only available in the Sydney, Wollongong, Newcastle and Gosford areas. An important point in the failure to provide these sentencing options is that they are generally at the heavier end of the sentencing scale and provide direct alternatives to the use of imprisonment. Thus courts are left with less alternatives to the use of imprisonment, and this particularly impacts on Indigenous people given that they are more likely to live in rural and remote areas, more likely to be before these courts, and are morelikely to be facing a term of imprisonment.

Similar problems have been identified in Queensland where sentencing alternatives are not available in remote communities for Indigenous adult and juvenile offenders because the relevant departments do not have the capacity to supervise court orders (Cunneen 2005:107-108). A result is that a range of sentencing alternatives and specific programs are not available. The outcome is that intermediary responses to offending behaviour are absent. Offenders either receive minimal sentences of unsupervised orders (and are then potentially more likely to re-offend) or they receive a harsher sentence of imprisonment. The failure to provide equitable services for Indigenous people in rural and remote areas entrenches their over-representation in the criminal justice system, and in particular in prison.

The Potential for Developing and Strengthening Indigenous Responses to Crime

One of the positive outcomes in relation to Indigenous people and the criminal justice system over recent years has been the growth in more grass roots Indigenous responses to crime. These alternatives approaches have included holistic anti-violence programs, community justice groups, Indigenous courts, and so on. Although many of these ‘alternatives’ are still very much within the existing non-Indigenous criminal justice system, they can help us to understand how Indigenous justice might develop as a distinctive response to Indigenous crime issues. In concluding this chapter, I want to refer very briefly to three initiatives: Aboriginal courts, community justice groups and night patrols.

Aboriginal courts (Circle sentencing, Koori Courts, Murri Courts and Nunga Courts) have been established for both adult and juvenile offenders in New South Wales, Victoria, Queensland and South Australia over the last few years. The courts typically involve an Aboriginal Elder/s or justice officer sitting on the bench with a magistrate. The Elder can provide advice to the magistrate on the offender to be sentenced and about cultural and community issues. Offenders might receive customary punishments or community service orders as an alternative to prison. Aboriginal Courts may sit on a specific day designated to sentence Aboriginal offenders who have plead guilty to an offence. The Court setting may be different to the traditional sittings. The offender may have a relative present at the sitting. The magistrate may ask questions of the offender, the victim (if present) and members of the family and community in assisting with sentencing options. The preliminary evaluations of these courts have been positive in terms of their impact on re-offending (see Harris 2004; Marchetti and Daly 2004;.Potas et al 2003; Cunneen 2005).

Aboriginal Justice Groups have been established in several jurisdictions in Australia. The groups are comprised of male and female community elders who provide advice to criminal justice agencies, and they may also deal with some justice matters themselves. Perhaps the most successful and certainly best evaluated have been the Aboriginal Justice Groups in Queensland (for a summary see Cunneen 2005:130-150). Aboriginal Community Justice Groups can work with police to issue cautions, establish diversionary options, support offenders, assist in access to bail, provide assistance to courts, and develop crime prevention plans. Evaluations of justice groups indicate they can achieve a reduction in juvenile offending and school truanting and a reduction in family and community disputes and violence. They can increase the more effective use of police and judicial discretion and provide better support for offender reintegration.

One of the longest running community-based crime prevention programs in Indigenous communities has been night patrols. They are also one of the few types of initiatives that have been evaluated at a more systematic level. Generally the evaluations have been very positive (Blagg and Valuri 2004). Evaluations of night patrols indicate they can achieve a reduction in juvenile crime rates on the nights the patrol operates, including for offences such as malicious damage, motor vehicle theft and street offences. They can work to minimise harm associated with drug and alcohol misuse, and they can enhance community perceptions of safety.

All of these initiatives can increase community self-esteem and empowerment. They can encourage Aboriginal leadership, community management and self-determination. These types of initiatives are important for their community capacity building effects. That is they can enhance the development of effective and culturally informed governance structures for communities, as well as defining matters of priority for the community.

Finally, it is important to note that many of the initiatives in Indigenous justice have developed in rural and remote areas. The night patrols began in communities like Yuendumu in the Northern Territory when Indigenous women sought greater control over community policing of alcohol and violence. Community justice groups began in Kowanyama because of dissatisfaction by Indigenous elders of mainstream government services like juvenile justice and corrections. Aboriginal courts began as initiatives between magistrates and elders to better deal with the problems of offending behaviour. Perhaps at this level, remoteness from centres of government power can be an advantage and an incentive to develop criminal justice structures more suited to the local environment.

References

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Women’s Task Force on Violence (2000) Final Report, DATSIPD, Brisbane.

ABS (2000) Report on Experimental Indigenous Socio-economic Disadvantage Indexes, Commonwealth Grants Commission, Canberra.

ABS (2003) Population Characteristics, Aboriginal and Torres Strait islander Australians 2001, Cat No 4713.0. http://www.abs.gov.au/Ausstats/abs@.nsf/e8ae5488b598839cca25682000131612/2b3d3a062ff56bc1ca256dce007fbffa!OpenDocument Accessed 10/4/06.

ABS (2004a) Experimental Estimates and Projections, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders Australians 1999-2009, Cat No 3238.0, Accessed 10/4/06. http://www.abs.gov.au/Ausstats/abs@.nsf/e8ae5488b598839cca25682000131612/4ef9b192cb67360cca256f1b0082c453!OpenDocument

ABS (2004b) National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders Social Survey 2002, Cat No 4714.0, http://www.abs.gov.au/Ausstats/abs@.nsf/e8ae5488b598839cca25682000131612/ad174bbf36ba93a2ca256ebb007981ba!OpenDocument

Blagg, H. and Valuri, G. (2004) ‘Self-Policing and Community Safety: The Work of Aboriginal Community Patrols in Australia’ Current Issues in Criminal Justice, vol 15, no 3, March 2004, pp205-219.

Criminal Justice Commission (1996) Aboriginal Witnesses in Queensland Criminal Courts, GoPrint, Brisbane.

Cunneen, C. (2001) Conflict, Politics and Crime, Allen and Unwin, Sydney.

Cunneen, C. (2002) Aboriginal Justice Plan Discussion Paper, Aboriginal Justice Advisory Council, Sydney.

Cunneen, C. (2005) Evaluation of the Queensland Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Justice Agreement, (unpublished).

Fitzgerald, J. and Weatherburn, D. (2001) ‘Aboriginal Victimisation and Offending: The View from Police Records’, Crime and Justice Statistics Brief, New South Wales Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research, Sydney.

Harding, R., Broadhurst, R., Ferrante, A. and N. Loh (1995) Aboriginal Contact with the Criminal Justice System and the Impact of the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody, Hawkins Press, Annandale.

Harris, Mark. (2004) ‘From Australian Courts to Aboriginal Courts in Australia- Bridging the Gap?’, Current Issues in Criminal Justice, , vol 16, no 1, July 2004.

Hogg, R. (2001) ‘Penality and Modes of Regulating Indigenous Peoples in Australia’ Punishment and Society, vol 3, no 3, pp 355-380

Hunter, B. (2001) Factors Underlying Indigenous Arrest Rates, New South Wales Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research, Sydney.

Lawrie, R (2002) Speak Out Strong: Researching the Needs of Aboriginal Women in Custody, New South Wales Aboriginal Justice Advisory Council, Sydney.

Luke, G. and Cunneen, C. (1995) Aboriginal Over-Representation and Discretionary Decisions in the NSW Juvenile Justice System, Juvenile Justice Advisory Council of NSW, Sydney.

Luke, G. and Cunneen, C. (1998) Sentencing Aboriginal people in the Northern Territory: A Statistical Analysis, NAALAS, Darwin.

Marchetti, Elena. and Daly, Kathleen. (2004) ‘Indigenous Courts and Justice Practices in Australia’, Trends and Issues No 277, AIC, Canberra.

Memmott, P., Stacy, R., Chambers, C. and Keys, C. (2001) Violence in Aboriginal Communities, Attorney-General's Department, Canberra.

Mouzos, J. (1999) 'New Statistics Highlight High Homicide Rate for Indigenous Women' Indigenous Law Bulletin, vol 4, no 25, pp.16-17

Moffat, S., Goh, D. and Poyton, S. (2006) New South Wales Recorded Crime Statistics 2005, NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research, Sydney.

New South Wales Legislative Council Standing Committee on Law and Justice (2006) Community-Based Sentencing Options for Rural and Remote Areas and Disadvantaged Populations, New South Wales Parliament, Sydney.

NSW Office of the Ombudsman (2000) Police and Public Safety Act, Office of the Ombudsman, Sydney.

Potas, Ivan, Smart, Jane, Bignell, Georgia, Lawrie, Rowena, and Thomas, Brendan (2003) Circle Sentencing in New South Wales. A Review and Evaluation. New South Wales Judicial Commission and Aboriginal Justice Advisory Committee, Sydney.

SCRGS (Steering Committee for the Review of Government Service Provision) (2005) Overcoming Indigenous Disadvantage Key Indicators 2005, Productivity Commission, Canberra.

Waters, J (2005) ‘Palm Island Housing’ Stateline Queensland, ABC Online. http://www.abc.net.au/stateline/qld/content/2005/s1471922.htm Accessed 2/5/06

[1] Much of the data on Indigenous issues uses a remote /non-remote divide. This has the effect of putting regional rural areas (which are not remote) with urban areas. Thus there are some problems when trying to discuss rural areas as distinct from both urban and remote.

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/UNSWLRS/2008/11.html