University of New South Wales Faculty of Law Research Series

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

University of New South Wales Faculty of Law Research Series |

|

Last Updated: 5 May 2008

Challenges in improving access to Asian laws:

the Asian Legal

Information Institute (AsianLII)

Graham

Greenleaf, Professor of Law,

University of New South Wales, and Co-Director,

AustLII

Philip Chung, Lecturer in Law,

University of Technology,

Sydney, and Executive Director, AustLII

Andrew Mowbray, Professor of Law,

University of

Technology, Sydney, and Co-Director, AustLII

Presented at the 4th Asian Law Institute

(ASLI) Conference -

“Voices from Asia for

a Just and Equitable World”, Jakarta, May 2007.

Accepted for

publication in the Australian Journal of Asian Law.

Abstract[*]

The Asian Legal Information Institute (AsianLII) <http://www.asianlii.org> is a free access legal research facility, developed by the Australasian Legal Information Institute (AustLII), in conjunction with partners in various Asian countries. Launched in December 2006, AsianLII now includes 120 databases from all 27 Asian countries, from Mongolia in the north to Timor Leste in the south, Japan in the east to Pakistan in the west. It includes about 150,000 full text cases, and over 15,000 items of legislation, plus law reform reports, a few law journals, and other materials. All of this content may be searched simultaneously, and individual country collections, or individual databases, may be searched separately. Some of the larger collections are from the Philippines, India, Singapore, and (for legislation) Timor-Leste and Vietnam. AsianLII also includes Hong Kong databases from HKLII, and Papua-New Guinea databases from PacLII, and Korean and Taiwanese databases from GLIN at the Law Library of the US Congress, exemplifying cooperation between members of the Free Access to Law Movement. AsianLII already receives over 50,000 ‘hits’ per working day. This paper discusses the challenges involved in building AsianLII, particularly in a region of such linguistic diversity: its rationale, technical features, approaches to partnerships, migration of technology and content control, and sustainability.

Introducing AsianLII

The Asian Legal Information Institute (AsianLII - www.asianlii.org - pronounced ‘Asian-lee’), is a non-profit and free access website for legal information from 27 countries and territories in Asia, from Mongolia in the north to Timor-Leste in the South, and from Japan in the east to Pakistan in the west. AsianLII is being developed by the Australasian Legal Information Institute (AustLII), a joint facility of the Law Faculties at the University of Technology, Sydney (UTS) and the University of New South Wales (UNSW), in cooperation with partner institutions in Asian countries and with other legal information institutes (LIIs) belonging to the Free Access to Law Movement.

AsianLII was launched on 8 December 2006 in Sydney jointly by the Co-Chair of the Conference of Chief Justices of Asia and the Pacific (the Chief Justice of Queensland) and the Deputy Director-General of AusAID. The Philippines launch of AsianLII in Manila on 10 January 2007, was by the Chief Justice of the Philippines and the Australian Ambassador. Similar launches will take place in other Asian countries.

AsianLII includes databases of legislation, case-law, law reform reports, law journals and other legal information. It already (as at April 2007) provides access to 120 databases with at least one from each of the 27 countries. So far, over 140,000 cases from fifteen countries, over 15,000 pieces of legislation from sixteen countries, law reform reports from seven countries, and four law journals are searchable. All databases can be searched simultaneously (eg from the front page of AsianLII), or searches can be limited to one country’s databases or other combinations. Search results can be ordered by relevance, by date, or by database, or by country.

Most databases are in English as yet, but there are substantial databases in Bahasa and in Portuguese. There is also a catalog of law web sites, and a ‘Law on Google’ facility, for each country, so as to provide more comprehensive research. The search software used by AsianLII (‘Sino’), and the hypertext mark-up software used to create its databases from text files, were developed by AustLII. Work is underway to develop the software further to enable searching of Asian languages.

This paper discusses the challenges involved in building AsianLII, particularly in a region of such linguistic diversity. We cover AsianLII’s rationale, technical features, approaches to partnerships, migration of technology and content control, sustainability, and plans for future development.

Background – Free access to law and legal information institutes

The Legal Information Institute started at Cornell University Law School in 1992 with databases primarily of US federal law was the first significant source of free access law on the Internet. The Australasian Legal Information Institute (AustLII) was started by UNSW and UTS Law Schools in1995. It borrowed the ‘LII’ suffix from Cornell, as others have done since, but was the first LII to attempt to build a comprehensive free access national legal information system rivaling that of commercial publishers.

From 1999 AustLII started to use its search engine (Sino) and other software to assist organisations in other countries to establish LIIs with similar functionality. The local partners usually had academic roots: in 2000, the British & Irish Legal Information Institute (BAILII), based at the Institute of Advanced Legal Studies, London and University of Cork; in 2001, the Pacific Islands Legal Information Institute (PacLII) at the University of the South Pacific Faculty of Law for fourteen island countries of the Pacific (now 20); in 2002 the Hong Kong Legal Information Institute (HKLII) at Hong Kong University; the Southern African Legal Information Institute (SAFLII) with Wits University Law school in 2003 (now operated by the South African Constitutional Court Trust for sixteen countries in southern and eastern Africa); and the New Zealand Legal Information Institute (NZLII) established by Otago University Law School in 2004. For all these LIIs, AustLII established the initial system and ran it for a while, with the aim of assisting full local take-over as soon as possible. Cylaw in Cyprus developed independently from 2004, but uses AustLII’s search engine.

Meanwhile, the long-established LexUM team at the University of Montreal established the Canadian Legal Information Institute (CanLII) in 2000, initially by using the AustLII software but then developing their own. They also developed Juri Burkina (2003), Droit Francophone (2003), and are assisting development of systems in other countries.

BAILII and PacLII were multi-country regional systems from inception, but did not involve material from other LIIs. A linguistic rather than regional focus was taken by Droit Francophone (2003), with initial content concentrating on West and Central Africa, but some databases from across the francophonie. It is a single LII but now includes content derived from Juri Burkina. WorldLII (2002) was the first multi-LII site, initially incorporating data from AustLII, BAILII, PacLII, HKLII and CanLII. Two multi-LII sub-portals followed. In 2005 AustLII developed the Commonwealth Legal Information Institute (CommonLII, 2005) for Commonwealth and Common Law countries (‘droit Anglophone’ is its nickname), which added databases from 20 new countries, but also relied upon the content of existing LIIs: AustLII, BAILII, CanLII, PacLII, HKLII, SAFLII and CyLaw. All of this fed back into WorldLII.

While this LII development was taking place, the Asian Development Bank also funded AustLII to develop a Catalog of external websites from every country in the world, and an associated websearch facility (Project DIAL 1997-2002). The ADB's intention was to provide governments and lawyers in Asian developing countries with a low-cost means of legal research via the Internet. From 2003-06 the Catalog's development was funded by the Australian Research Council (ARC). AustLII staff used the DIAL resources in 2000-2002 to train government lawyers from seven Asian countries (Indonesia, Pakistan, Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, China and Mongolia) in legal research techniques (see DIAL 2002). The catalog and websearch became part of WorldLII.

Rationales for an Asian law portal

Asia is a region with many different legal systems, as well as one of linguistic and cultural diversity. The traditional historical influences on its legal systems differ widely because of its huge geographical spread, and the influences of colonial legal systems are equally diverse. Some legal systems are influenced principally by the civil law systems of western Europe (Japan, South Korea, Indonesia etc), and often different civil law systems at that (French, German, Dutch etc). An equal number are based on the common law system of England (Pakistan, India, Singapore, Malaysia, Brunei, Sri Lanka etc), and some on US-derived common law (The Philippines). Yet others are influenced by the legal systems developed in the former Soviet bloc countries as well as by civil law traditions (Vietnam, China, North Korea, Mongolia etc). Compared with the legal systems of Europe, where civil law influences dominate, South and Central America with a relatively consistent Iberian civil law heritage, or Africa where there are two predominantly influences (English common law and French civil law), the hallmark of Asia is diversity if you take a pan-Asian view.

Despite this apparently unpromising start to the prospect of an Asia-wide legal information system, there are nevertheless sufficient common factors to make such an enterprise worthwhile, if daunting. They can summed up as trends toward hybridization (perhaps even covergence), the value of transparency, and the value of the rule of law.

The first factor indicating feasibility is that the differences may be reducing. Is a convergence of Asian and Western legal systems occurring? While this is a much larger topic than is the subject of this paper, it is sufficient to note that many authors do see such a trend. A survey by the Asian Development Bank over the 35 years 1960-1995 (Pistor, Wellons, Sachs and Scott, 1998) reached a cautious conclusion that the differences were diminishing:

Thirty five years after the onset of high growth in Asia, market-oriented law had come to play a greater role in Asian economies than in the past. Even in the past, however, law played a role in economic development as handmaiden to government economic strategy. Law was not irrelevant to the economy. During the thirty five years, differences in legal systems between Asia and the West diminished, particularly in the substance of the law. The patterns of legal and economic change in Asia suggest that substantial differences in legal process persist. However, this does not necessarily justify the assumption that legal systems in Asia will continue to diverge from those in the West. The variety in Asia’s growth resembles the many paths of economic and institutional change taken historically in the West, where substantial differences in legal systems and the structure of economies remain to this day.

The theme of the 2006 ASLI Conference was ‘Convergence versus Divergence’. In his opening address Grand Justice Cao Jianming stressed both that ‘although great differences exist among nations in history, religion, culture and even legal tradition, they have ultimately taken the road to rule of law’ and that ‘we should recognize the differences in different nations’ effort to develop their legal systems’ (Jianming, 2006). Notions of convergence must obviously be treated with caution.

It is more clear that in many Asian countries there is increasing hybridization of the influences and models that are used to reform particular aspects of their legal systems. Instead of a consistent adoption and development of models from one particular tradition such as the civil law, English common law or US common law, there is increasing borrowing from a variety of traditions depending on which models are seen as more internationally successful, particularly in the advancing economic development. This process has been advanced a great deal by the practices of international aid organizations in funding legal reform projects involving international experts over the last 45 years. The ever-increasing number of international agreements requiring local laws to be made consistent with an international standard, and the pressures from regional organizations such as APEC, SAARC and ASEAN for regional harmonisation of some laws increases the trend (see for example APEC 2006). To the extent that hybridization or convergence is occurring, it makes the facilitation of comparative law research within Asian legal system more valuable.

Increased transparency of legal systems is one of the common features of conditions of accession to the World Trade Organisation, and may even include a requirement that laws be available in other than national languages. For example “China specifically agreed to translate into one of the WTO languages and make publicly available all WTO-related law, to apply such law in a uniform and neutral manner, and to allow judicial review of administrative decisions relating to such implementation” (Halverson, 2004). From this perspective the advantage that a system like AsianLII provides is that it enhances transparency to the outside world.

The front page of AsianLII – extract as at 29 April 2007

The complementary argument is that increased transparency of a country’s legal system to its own citizens supports the rule of law, while at the same time helping demonstrate the effectiveness of the rule of law to the ‘outside’ world. In various countries across Asia there is still a tension between the rule of law and rule by law (Spigelman 2002, 2003). In this conflict any increase in transparency of a country’s laws to its own citizens falls clearly on the side of supporting the rule of law: it both informs citizens of the laws they are subject to, and of the precise rules by which government agencies and other powerful institutions are also subject to those laws.

Multi-source site within Asian jurisdictions

An additional, perhaps surprising, value of AsianLII is that it provides a demonstration of the value of making various categories of documents from within a country (legislation, decisions from different courts, treaties etc) available on the one site and jointly searchable. It is often difficult for separate government agencies and courts to cooperate directly in order to achieve this. It is rare for Asian governments to build free access websites for all legal resources for a county (Sri Lanka’s LawNet is an exception, and Singapore’s LawNet is a pay-for-use example). The inclusion of databases from various agencies and courts on a country’s page on AsianLII (as in the Philippines illustration following) gives a demonstration of the advantages of creating more comprehensive national sites.

Emergence of AsianLII

AustLII’s work from 1999-2002 laid the foundations for the development of AsianLII. We learnt from Project DIAL that there was a high demand in Asian countries for an easy way to research law from many countries across the world, including other Asian countries, but that a catalog of websites could not deliver this by itself. However, it did mean we had an extensive catalog of legal websites for every Asian country, and developed valuable working relationships in seven Asian countries. The creation of CommonLII in 2005 resulted in our developing databases for seven of the eight Commonwealth countries in Asia, including extensive databases from India and Singapore. We had already developed some substantial databases from non-Commonwealth Asian countries (Indonesia, Cambodia and Timor-Leste) on WorldLII. HKLII and PacLII already provided databases for Hong Kong and Papua New Guinea which were available for inclusion through LII cooperation. With databases already available from twelve of the twenty seven Asian countries it was therefore feasible to develop an Asia-wide legal database system, and this became AsianLII. In 2006 Ausaid and the Australian Attorney-General funded development of further databases from the Philippines, Vietnam, China, Malaysia and Thailand. By the end of 2006 the rudiments of an Asia-wide system were therefore in place, sufficient to justify its launch. Of course, AsianLII currently contains only a fraction of the Asia-wide legal information which it would be desirable to have available in a convenient and moderately consistent form.

Other Asia-wide systems

Has such a system already been built for Asian law? There are few Asia-wide law websites. The Asian Legal Information Network (ALIN) <http://www.e-alin.org/> describes as one of its aims “The creation of an online database of statutes, cases, Official Gazettes and any other legal information of Asian countries which will be freely available to Asian legal information-related institutions or organizations”. It is managed by the Korea Legislation Research Institute (KLRI) in conjunction with many prominent law schools and research institutes across the region. At present it provides for public access 145 research papers, laws etc contributed by its member institutions, and may provide more for ‘members only’ access.

Sub-regional organisations provide some multi-country information. ASEAN <http://www.aseansec.org/> provides regional agreements. The ASEAN Law Association site <http://www.aseanlawassociation.org/> , for a regional association of lawyers, has a valuable set of introductions to the legal systems of ASEAN countries, and speeches and papers concerning the law of each country. The South Asian Association For Regional Cooperation (SAARC) has a website <http://www.saarc-sec.org/> which provides some information about regional agreements. The South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation in Law (SAARCLAW) is a regional organisation of lawyers, judges, law teachers, legal academician and legal researcher of SAARC countries. Its website <http://www.saarclaw.com/> contains its newsletter on regional law developments, speeches and other publications.

None of these systems provides a substantial comparative research facility for cases and legislation from across all Asian countries, or for any part of the Asian region.

Contents of AsianLII

Does AsianLII start to fill this gap? What information does it provide at present? A somewhat more detailed description of its contents than is given in the introduction is now needed in order to establish its credentials. As at April 2007 AsianLII provides access to 120 databases with at least one from each of the 27 countries.

Legislation

Over 15,000 pieces of legislation from sixteen countries are included. The largest legislation databases are from Vietnam (2462 laws), China (1478 laws), India (1049 Acts from 1836), Singapore (536 consolidated Acts) and Sir Lanka (516). Other significant legislation collections are from Indonesia and Cambodia. The comprehensiveness and currency of this legislation varies considerably. For example, the Sri Lankan legislation is a 1980 consolidation, and is being updated from the Sir Lankan Lawnet site. There are nine separate Philippines legislation databases. HKLII and PacLII maintain up-to-date legislation from Hong Kong and PNG. GLIN provides English summaries of almost 3,000 pieces of Korean legislation, and the full texts in Hangul. Constitutions from most Asian countries are included as separate databases, and there is a separate page for comparative constitutional searches.

Court decisions

So far, over 140,000 cases from fifteen countries, are included, the largest databases being from the Supreme Court of the Philippines (46,505 decisions from 1901), the Supreme Court of India (21,642 decisions from 1950), the Supreme Court of Sri Lanka (1,100, only to 2000 but now being updated). There are other large case law collections from India (13 High Courts) and the Philippines (3 courts). Decisions of the Courts of Singapore and Malaysia at various levels are included but only from recent years. HKLII and PacLII maintain large collections of the decisions of numerous Courts from Hong Kong and PNG. AsianLII also provides summaries in English of the decisions of the highest courts of Japan, South Korea, Thailand and Taiwan. The extensive Benchbook of the Supreme People's Court of Vietnam is a new type of judicial database, increasing the transparency of Vietnam’s judicial process.

Other content

Law reform reports from seven countries are included (Bangladesh, India, PNG, Hong Kong, Pakistan and Singapore), and are jointly searchable. A collection of law journals has commenced, small as yet with four journals from Japan, the Philippines, India and Malaysia. Treaties and agreements are not yet well represented, but there are small databases from Singapore, ASEAN, APEC and SAARC. The virtual databases discussed below address some of these limitations in content.

Virtual databases – International court decisions and law journals articles

Some databases of the World Legal Information Institute (WorldLII) include data of direct relevance to Asian countries. This information is being ‘data mined’ from WorldLII (and therefore from any other LIIs) and included as ‘virtual databases’ on AsianLII. For example, wherever the decision of an international Court or Tribunal included on WorldLII has an Asian country as a party, that decision will also be searchable on AsianLII. Wherever a law journal or legal scholarship repository on WorldLII refers to an Asian country in its title, that article will be searchable on AsianLII. Where there are any bilateral treaties involving Asian countries in the treaties collections on WorldLII, they will be searchable on AsianLII.

Data collection approaches

How data is acquired for AsianLII’s databases varies a great deal. The local involvement may be passive because a court or legislation website indicates that others are allowed to republish its content. Alternatively the copyright law of a jurisdiction may state there is no copyright in classes of legal documents for that whole jurisdiction. Examples are s52(q) of India’s Copyright Act 1957, or Article 6 of Macau's Copyright Law (Decree-Law no 43/99/M of August 16, 1999), or s9 of Sri Lanka’s Code of Intellectual Property 1979. This last section provides that copyright ‘protection shall not extend to (a) laws and decisions of courts and administrative bodies, as well as to official translations thereof’, and the Macau provision is in much the same term.

In contrast, a local partner institution may actively provide data to AsianLII which they have the right to publish, as in the Philippines or Thailand. In other cases obtaining republication rights requires requests and negotiation of terms with data sources (for example with the Singaporean data in AsianLII), but requests are rarely refused if the data is already being published for free access. The information is then extracted from the organisation’s website with its consent. In other cases negotiating the supply of a stream of otherwise unobtainable data can be very difficult, particularly if a commercial provider is already obtaining it (eg Malaysian legislation). Sometimes a government institution concerned is pleased to obtain an opportunity to publish on the Internet which is otherwise not readily available to it (though this is increasingly rare). PacLII and SAFLII have staff members who travel from country to country to obtain data not otherwise available, and AustLII does this in the limited number of countries where it has funding for AsianLII. A discussion of the many complexities of data acquisition would be very lengthy. It is sufficient to say that both AsianLII and the LII network generally have only scraped the surface of the valuable legal information which is potentially available. The key is to build up long-term relationships which facilitate the continuing supply of data.

Search facilities and value-adding

The most obvious advantage of AsianLII is that all its databases (and those of its collaborating LIIs) can be searched simultaneously, from its front page and elsewhere. The Sino search engine is very fast, and can search the full text of the approximately 200,000 documents on AsianLII in under a second for anything but the most complex searches.

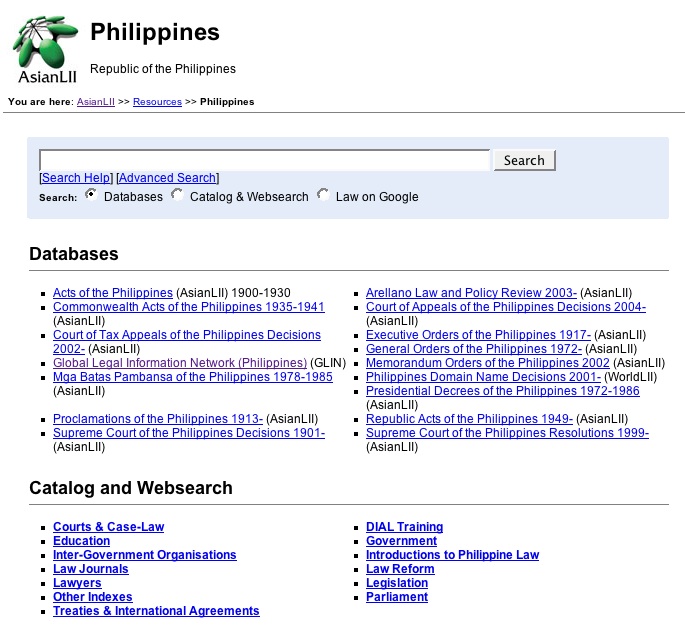

Searching the law of individual countries/economies

The following screen illustrates how AsianLII works in relation to each country or economy’s laws included in it. The default search option ‘Databases’ results in a search of all the databases for that country held on AsianLII or a collaborating LII (such as HKLII, PacLII, GLIN or WorldLII). In the example below, all 14 databases are searched jointly from the Philippines page, but can be searched separately from each database’s home page.

The second search option, ‘Catalog & Websearch’, results in a search of other websites relating to Philippines law, those listed in the extensive Catalog of law-related Philippines websites at the bottom of the Philippines page. The third option ‘Law on Google’ will run the same search over the Google search engine, after translating it into the correct search syntax. It will also limit the search scope to websites from the Philippines, or those mentioning the Philippines, and only if they relate to legal subject matter. Details of these options are in the AsianLII User Guide obtainable from the front page of AsianLII.

Extract from the Philippines page on AsianLII

Searching across only legislation or case law from multiple countries

The ‘Advanced Search’ facility on AsianLII’s front page (see the first illustration) allows a user to select ‘All legislation databases’, or ‘All case law databases’ or ‘All law journals databases’ to carry out specialised comparative research across Asian countries.

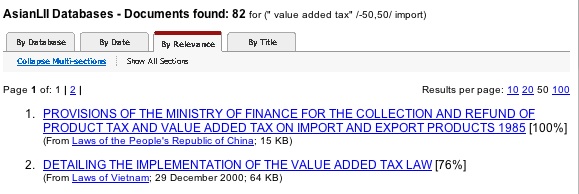

Search results display options

Search results may be displayed in a variety of ways. In default they are displayed in order of relevance to the search request as assessed by Sino’s relevance ranking algorithm. As illustrated below, they can be displayed by date (most recent documents first), or results may be grouped by database and then the results from particular databases displayed separately. Where search results contain multiple sections from one piece of legislation, they can be grouped together with only the first one shown (‘collapsed multi-section’), so that the rest of the results can be more easily seen.

Extract from default results of a search for ‘value added tax near import’

Searching regional groupings – ASEAN, SAARC and APEC

On AsianLII’s front page are options allowing users to go to pages for each of the regional groupings ASEAN (7 countries), SAARC (7 countries) and APEC (13 Asian economies, though APEC also has non-Asian members). These page enable users to search only the databases from countries/economies in the grouping, plus a database of ‘Agreements and Declarations’ from the regional organization. There is also a catalog of web sites relating to the regional organization and its members. These pages are therefore ‘sub-portals’ for legal information from these regional groupings.

Usage

Although AsianLII was only launched 4 months ago, it is already receiving substantial use. For the January-March 2007 quarter the eleven AsianLII countries whose databases have accounted for the largest numbers of accesses are PNG (496,025), Philippines (435,347), India (198,374), Hong Kong (117,105), Sri Lanka (63,044), Indonesia (41,514), Macau (24,528), Vietnam (21,762), Singapore (11,084), China (9,559), and Thailand (8,147). There were another 25,000 accesses to the databases of another 16 AsianLII countries, giving a total of about 2,250,000 database accesses. Accesses to the Catalog pages, home page and menus amount to approximately 1,200,000. Therefore, in 3 months, there have been about 4,450,000 accesses, or about 1,150,000 per month or over 50,000 per working day. The distribution is, as expected, favouring jurisdictions with the largest databases. The project appears to be achieving its aim of increasing transparency of Asian legal systems, with AsianLII meeting a previously unmet demand for better access to legal information from Asian countries.

The statistics also indicate that AsianLII is already starting to achieve the project aim of improving inter-Asian access to legal information. The top 10 jurisdictions from which accesses to AsianLII can be identified as coming include Indonesia, the Philippines, Singapore and Japan, averaging about 9,000 accesses per country over 3 months. Malaysia, PNG, India and Hong Kong are included in the next 10 countries. Unfortunately the domains of 55.67% of all enquirers cannot be resolved, and this problem occurs disproportionately in developing countries, so there is a large ‘dark figure’ of unidentifiable accesses which may include a high percentage of access from Asia. A reasonable assumption is that the actual usage from Asian countries is at least double the figures given above (ie 6,000 accesses per month from the top 4 countries). There are also over 1,300 links to AsianLII from other websites around the world, indicating early recognition of its value.

Partnerships, support and sustainability

AsianLII’s viability depends on its relationships with, and support from, organisations in the Asian region. These include sources of data in each country, organisations with whom we are working to increase their own capacity to provide legal information (including law schools and government agencies), regional organisations (of governments, the legal profession and others), and the other LIIs who contribute to AsianLII’s content. These relationships are acknowledged in the ‘Stakeholder’ section accessible from AsianLII’s front page.

Partner institutions, and encouraging local capacity

It is essential to the viability of AsianLII that AustLII develops collaborative relationships with one or more institutions involved in the provision of legal information in as many as possible of the countries covered by AsianLII. So far, AustLII has concentrated on forming such relationships in those countries covered by its funding (as discussed below), but is gradually developing such relationships wherever possible. Our counterpart organizations to date are Arellano School of Law, and CD Asia Ltd (the Philippines), the Office of the Council of State in Thailand, the Institute of Law Research, Ministry of Justice of Vietnam, the University of Hong Kong and the University of Macau Faculty of Law (China), the Royal University of Law and Economics in Cambodia, and the M.K. Nambyar SAARCLAW Centre at the National Academy of Legal Studies and Research University (NALSAR) in India. We also cooperate directly with other projects such as the Indonesia Australia Legal Development Facility (IALDF).

The basis of these relationships varies, and will change over time. At the level of More intense collaboration it is likely to include the provision of AustLII’s Sino search engine and other software for LII development, and may also include AustLII support for applications by local partners to obtain resources, typically from international aid organisations. Part of the aim of the AsianLII project is to assist in the development of the local capacity of our partner organisations to develop and maintain independent local legal information to international best practice standards, and to integrate them into international free-access law networks such as AsianLII, CommonLII and WorldLII. Where possible and requested, AustLII provides technical assistance to our partner institutions to help develop these capacities.

We hope to gradually develop a wider range of collaborating institutions from all Asian countries, but this takes time. Expressions of interest are welcome from law schools, courts and government agencies, and other organisations involved in the provision of legal information.

Collaborating LIIs, networking, and the Free Access to Law Movement

The databases searchable via AsianLII will in most cases be located on the AsianLII servers located at AustLII, where they will be converted into a common format. In many cases the same data will also be able to be obtained from the websites of our local partners. Where countries in AsianLII are also Commonwealth countries (Pakistan, India, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Brunei, Malaysia, Singapore) the databases are shared with CommonLII (the Commonwealth Legal Information Institute) and have a CommonLII logo rather than an AsianLII logo simply because CommonLII was developed in 2005 before AsianLII.

A significant portion of the databases accessible via AsianLII are maintained by other independent free-access legal information institutes, not by AustLII. At present these are the Hong Kong databases from the Hong Kong Legal Information Institute (HKLII), the Papua New Guinea databases from the Pacific Islands Legal Information Institute (PacLII), and the South Korean and Taiwanese legislation databases from the Global Legal Information Network (GLIN) at the US Law Library of Congress (with abstracts in English and the full text legislation in Hangul and Chinese respectively).

Data access relationships in the networking of LIIs (April 2007)

Where there is an independent local legal information institute (such as HKLII or PacLII) providing some of the data, a constantly synchronised mirror copy of the LII is located at AustLII for searching purposes, but search results from AsianLII searches return the user to the local LII. We expect that this will soon be the case for LAWPHIL in the Philippines, and probably in some other Asian countries within a year or so.

All databases available through AsianLII are also thereby searchable via the World Legal Information Institute (WorldLII) <http://www.worldlii.org> , which contains databases from over 100 countries provided by 15 independent legal information institutes (‘LII’s). The current interconnections in this network are as above. The LII network relies upon a replication / synchronisation model (see Mowbray, Chung and Greenleaf (2007) for detail, and Greenleaf, Mowbray and Chung 2007 for an outline).

The LIIs whose data is searchable via WorldLII also belong to the Free Access to Law Movement (Declaration, 2002-04). The Declaration asserts the right of independent free access publishers to republish ‘public legal information’, defined as meaning

“legal information produced by public bodies that have a duty to produce law and make it public. It includes primary sources of law, such as legislation, case law and treaties, as well as various secondary (interpretative) public sources, such as reports on preparatory work and law reform, and resulting from boards of inquiry. It also includes legal documents created as a result of public funding.”

It encourages all ‘legal information institutes’ to participate in regional or global free access to law networks.

Regional supporting organisations

We are seeking the support of regional law organisations for the provision of legal information via AsianLII. APEC’s SELI (Strategic Economic Legal Infrastructure) Coordinating Group is a key supporter. LAWASIA has endorsed AsianLII in these terms:

“LAWASIA, the Law Association for Asia and the Pacific, endorses and supports AsianLII, and LAWASIA's international Council encourages all countries in the region to cooperate in the development of AsianLII through enabling access to all relevant legal materials.”

The International Development Law Organisation (IDLO) endorses AsianLII in similar terms. Discussions are continuing with the Inter-Pacific Bar Association, the Asia Project of the American Bar Association, and the Asian Development Bank, about such endorsement and cooperation. Other regional support is welcome. The Conference of Chief Justices of Asia and the Pacific has invited an AsianLII presentation to its June meeting in Hong Kong.

Funding and sustainability

AustLII received initial funding support for the development of AsianLII’s infrastructure from the Australian Research Council in 2006. AusAID’s Public Sector Linkages Programme (PSLP) assists development linkages between Australian public sector organisations (such as Universities) and those of Asian countries. Ausaid is providing PSLP funding for the inclusion of content from six jurisdictions (Indonesia, Cambodia, Thailand, Vietnam, the Philippines, and China including Macau and Hong Kong). Inclusion of content from four other jurisdictions is provided by the Australian Attorney-General’s Department (India, Singapore, Malaysia and China). Current funding is sufficient to support one full-time staff member at AustLII to build AsianLII databases, plus support overheads equivalent to another half a person, so the minimum infrastructure needed is relatively modest and capable of being sustained. Applications have been submitted to various aid bodies for support for the development of aspects of AsianLII’s content.

Future developments and priorities

Asian languages – searching and interfaces

English is an official language, used for legislation and court decisions, in more countries in Asia than any other language. Asian legislation and case summaries are more often translated into English than any other language. English language materials were therefore the sensible starting point for an Asia-wide law portal. Our initial aim is to include in AsianLII as much legal information as possible in the English language, so as to provide a common language platform (‘lingua franca’ isn’t quite the expression) for comparative legal research.

Having developed an initial set of English-language databases, we will now obtain for inclusion in AsianLII legal materials in the languages of countries/economies other than English. Databases in Bahasa (4) and Portuguese (2) have been added, as AustLII’s search engine (Sino) can already search those languages. There is limited utility in adding databases in languages which cannot be searched, except where a one-to-one link can be established between the searchable English language pages and pages in the other language, as with the Supreme People's Court of Vietnam Benchbook which is on AsianLII in English and Vietnamese with interlinked pages. GLIN also provides English summaries linked to laws in Chinese and Korean.

Sino is now being developed to allow it to search data in any language, including Asian scripts which currently use ASCII-based double-byte character encodings. However, the legal texts concerned will first have to be converted into Unicode (see Unicode home page and Wikipedia ‘Unicode’), using Unicode’s UTF (Unicode Transformation Format) encodings, unless they are available in Unicode already. The priorities for the development of Sino’s Asian language search capacity are Vietnamese and Chinese. We expect that progress will be made during 2007.

The interface to AsianLII also needs to accommodate languages other than English. Our current thinking is that wherever databases from a country are available on AsianLII in a language other than English, the home pages etc of the database should be in that language, and the ‘country page’ should be available in both that language and English. These processes can be automated after the translation of a standard set of terms, and are therefore sustainable within the low budget environment within which AsianLII must operate.

Content priorities – Primary materials first, then scholarship

Our initial priority is to include as much legislation and case law as can be obtained from each country, within the resources available to us. The second level of priority is to include treaties, law reform reports and law journals. A particular contribution that AsianLII could make is as a regional free access repository for law journals and journal articles, an alternative or complement to making those journals available through international commercial publishers such as Hein Online. AustLII has had success in this role in Australia, and now has nearly 50 Australian and New Zealand journals in its Australasian Law Journals Library. The content development of AsianLII will need to be measured in years not months. This is a first Annual Report.

The complementary priority – Fostering independent LIIs

None of this technical and content development will be sustainable unless we place a high priority on developing working relationships with institutions in Asian countries, encouraging them to develop their own free access provision of national legal resources (often but not always independent of government), and assisting them technically to do so to international best practice. This will usually result in the country’s materials continuing to be available to regional and international networks, but supplied with both quality and quantity improved. It removes the need for these resources to be maintained centrally, creates an increasingly valuable network, and makes it sustainable.

References

APEC 2006 Asia_Pacific Economic Cooperation Key APEC Documents 2006, APEC Secretariat, 2006

Declaration 2007 Declaration on Free Access to Law Free Access to Law Movement 2002-07 at <http://www.worldlii.org/worldlii/declaration/>

Greenleaf, G, Mowbray A and Chung P ‘Networking LIIs: How free access to law fits together‘ Internet Newsletter for Lawyers, UK,March/April 2007 at <http://www.venables.co.uk/n0703liisnetwork.htm>

Halverson K. ‘China’s WTO Accession: Economic, Legal, And Political Implications’ Boston College International and Comparative Law Review, 2004, available at <http://www.bc.edu/schools/law/lawreviews/meta-elements/journals/bciclr/27_2/06_TX>

Jianming, Cao, Grand Justice of the first rank and Vice President of the Supreme People’s Court of the People’s Republic of China Opening Address to the 3rd Asian Law Institute Conference: The Development of Law in Asia: Convergence versus Divergence? Shanghai, May 25th, 2006, available at <http://law.nus.edu.sg/asli/news/news13062006_2.htm>

Mowbray, A., Greenleaf, G., Chung, P. and Austin, D. (2007) ‘Improving stability and performance of an international network of free access legal information systems’ ARC eRsearch Seminar, Canberra, February 13-14, 2007, available at <http://law.bepress.com/unswwps/>

Pistor, K., Wellons, P. A., Sachs, J. D. and Scott, H S., Senior Advisors, Asian Development Bank The Role of Law and Legal Institutions in Asian Economic Development 1960-1995 - Executive Summary, Asian Development Bank, 1998, available at <http://www.adb.org/Publications/subject.asp?id=153>

Project DIAL 1997-2002 - Project DIAL home page <http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/special/dial/>

Spigelman, Hon. J J ‘The Rule of the Law in the Asian Region’ International Legal Services Advisory Council Conference, Sydney, Australia, 20 March 2003, available at <http://www.ag.gov.au/www/agd/agd.nsf/Page/RWPB779BB1E0FF6C2C5CA257199000AC9AF>

Spigelman, Hon. J J ‘Convergence and the Judicial Role: Recent Developments in China’ XVIth Congress of International Academy of Comparative Law, 16 July 2002, available at <http://www.lawlink.nsw.gov.au/lawlink/supreme_court/ll_sc.nsf/pages/SCO_speech_spigelman_110702> and in (2003) Revue Internationale de Droit Compare

Unicode home page - <http://unicode.org/>

Wikipedia ‘Unicode’ entry - <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Unicode>

[*] Acknowledgments: Thanks to all of AustLII’s staff who have worked on the databases and catalog available through AsianLII, particularly Kieran Hackshall. Thanks also to Ausaid, the Australian Research Council and the Australian Attorney-General’s Department for their support for this project. A revised version of this paper is to be published in the Australian Journal of Asian Law <http://www.law.unimelb.edu.au/ajal/> , and should be cited.

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/UNSWLRS/2007/42.html