|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

Upholding the Australian Constitution: The Samuel Griffith Society Proceedings |

Chapter One

The Case for Increased Commonwealth Involvement in Health

Andrew Podger

The case for increased Commonwealth involvement in health is not based on the poor performance of the States and an assumption of better performance by the national government. It is based in part on Australia’s history, but primarily on external factors including changing demands on the health system, changing expectations, and the need for cost controls which promote efficiency and effectiveness and do not undermine equity or quality. Each of these factors can only be addressed successfully by having a single government funder and purchaser of health and aged care services. For Australia, that is only possible if the Commonwealth is given this role.

The Commonwealth has steadily increased its share of government funding of health since federation, and has in fact been the dominant government funder since the 1950s.

Figure 1: Shares of Government Spending on Health1

From a very limited role focussed on human quarantine, the Commonwealth role expanded2 following the First World War, then again following the Second World War, and steadily thereafter. Medibank and Medicare in the 1970s and 1980s continued trends already firmly in place.

The initial jump after the First World War was in response to two factors: the needs of our returning soldiers, many of whom were injured or sick, and the impact of the influenza pandemic which demonstrated the need for national action beyond human quarantine to address communicable diseases. The second factor led to establishment of the Commonwealth Department of Health in 1921 with the encouragement and financial assistance of the Rockefeller Foundation.

The next major expansion came after the Second World War following deliberations in the Parliament during the war about the financing of the war effort and the case for offering the Australian community, who were being asked to pay so much, better social security once the war was over. Health insurance was part of a broader menu of social benefits proposed, including unemployment and sickness benefits and housing support. Not all were enacted and implemented, and the health insurance measures in particular required a change to the Constitution as well as lengthy and fractious debate with the medical profession. Nonetheless, by the end of the 1940s, Australia had a Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) and a Hospital Benefits Act 1945 (Cth), the latter directing money via the States. The Commonwealth Rehabilitation Service was also established at this time.

A compromise was reached with the medical profession in the Page Plan under Menzies which introduced a Pensioner Medical Service, with the rest of the population utilising private health insurance with Commonwealth subsidies and regulation. The steady expansion under Menzies of these programs, along with the PBS, took Commonwealth health funding above that of the States. The Coalition Government also introduced the Aged Persons Homes Act 1954 (Cth), and later the Aged Persons Hostels Act 1972 (Cth), beginning the process of Commonwealth domination of the aged care area.

Medibank in 1975, reintroduced as Medicare in 1984, added further to the Commonwealth’s share of health funding but on a base which by then was well over 50 per cent. It has since remained at just under two-thirds of total government spending on health.

A selective summary of major Commonwealth developments in health since Federation is set out in Table 1.

Table 1: Major Commonwealth Initiatives Since Federation

|

Decade

|

Major Commonwealth Initiatives

|

|

1900s

|

Federal Quarantine Service

|

|

1910s

|

Repatriation Commission

Commonwealth Serum Laboratories

|

|

1920s

|

Commonwealth Department of Health

|

|

1930s

|

National Health and Medical Research Council

|

|

1940s

|

Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme

Commonwealth Rehabilitation Service

|

|

1950s

|

Page Plan (Pensioner Medical Service (PMS), private health insurance

subsidies and regulation, school milk program)

Aged Persons Homes Act

|

|

1960s

|

Expansion of Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS), PMS, residential aged

care

|

|

1970s

|

School Dental Scheme

Medibank (Medical Benefits Scheme, free public hospitals, community health

services)

Medibank Marks 2 and 3 (means tests, PHI subsidies)

|

|

1980s

|

Medicare (similar to Medicare Mark 1)

Therapeutic Goods Administration

Better Health Commission

Australian Institute of Health

|

|

1990s

|

General Practice Strategy (GP Divisions etc)

National Food Authority

Office of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health

Private health insurance subsidies, life-time community rating

Community aged care expansion, Aged Care Standards and Accreditation

Agency

Australian Council for Quality and Safety

|

|

2000s

|

Expansion of General Practice Strategy, community aged care

Australian Radiation Protection and Nuclear Safety Authority; Gene

Technology Regulator

National E-Health Transition Authority

COAG agenda including national regulation of health workforce

|

Apart from the level of funding, there have been a number of recurring debates about the nature of the Commonwealth’s role.

The idea of national insurance, aimed to protect Australians from the adverse financial impact of various life events, has attracted significant political support on a number of occasions. National health insurance, along with national superannuation, was debated long and hard in the 1930s and 1940s, and again in the 1970s (along with national compensation) and 1980s. This debate encompassed issues such as whether governments should simply focus on protecting people from poverty, such as through means-tested pensions and benefits financed from general revenue, or whether they should assist people to maintain their living standards in retirement or sickness or unemployment with earnings-related benefits financed through compulsory insurance contributions.

Broadly, Australia’s preference for focussing government action on poverty alleviation financed from general revenue has prevailed, though in health a preference towards universal coverage can be detected well before the introduction of Medibank and Medicare with the steady expansion of the earlier schemes. Whichever approach has been favoured, there has long been strong support for national rather than State-based financial protection.

A second recurring debate has been whether Commonwealth involvement in health should be limited to the financing of health insurance, or include the provision of health services. As part of the Commonwealth’s repatriation program, it became involved in direct provision of hospital and medical services for veterans. In the 1920s and 1930s the first Director-General of Health, John Howard Lidgett Cumpston, wanted the fledgling Medical Service (established to support the military and the public service, and immigration activity) to become a national health service delivery organisation. He was thwarted by the Treasury which agreed there was a case for insurance, but not for Commonwealth involvement in providing health services. Whitlam also had dreams of the Commonwealth taking over hospitals and running community health services. Sid Sax, head of the Hospitals and Health Services Commission from 1972 to 1978, talked him out of most of this ambition, suggesting, instead, the Commonwealth-State Hospitals Agreement (nowadays, the Australian HealthCare Agreements), with increased Commonwealth funding conditional on free public patient hospital care. The Commonwealth’s direct involvement in community health under Whitlam was limited and short-lived.

The Commonwealth’s direct involvement in hospitals was substantially wound back in the 1990s in line with New Public Management reforms. Repatriation hospitals were privatised or handed back to the States, and the Department of Veterans’ Affairs became the purchaser rather than the provider of services for veterans. Nonetheless, for both veterans and the general public, the Commonwealth’s insurance role became more hands-on during the 1990s and 2000s with more sophisticated purchasing rather than simply reimbursing costs, and the establishment of structures and processes aimed at improving the quality and effectiveness of services. While not involving direct service delivery, initiatives such as establishment of GP divisions and introduction of payments to GPs for computers and nurses and allied health along with rewards for high levels of immunisation and cancer screening, etc, all increased Commonwealth influence in delivery of health services. Similarly, the last 25 years have seen a wide range of Commonwealth initiatives affecting the delivery of services, both through direct funding of service providers such as Aboriginal Medical Services and through conditional grants to the States.

A third recurring issue has been the role of private health insurance. This debate mirrors, to a large extent, the debate about national insurance, with those advocating the latter giving lower priority to the role of private health insurance. Sir Earle Page, Minister for Health from 1949 to 1955, limited the insurance role of the government itself to medical benefits in respect of pensioners, and pharmaceutical benefits, encouraging most Australians to take out private health insurance which was then subject to community rating regulation; Medibank/Medicare made Private Health Insurance far less important. In the 1990s, the steady fall in Private Health Insurance coverage, exacerbated by community rating regulation which had not been removed when Medicare was introduced, was adding to public hospital costs. Both sides of politics, having agreed to support universal Medicare, now looked for options for a complementary role for Private Health Insurance that might be sustained. Commonwealth subsidies were introduced in recognition of the savings to Medicare from reduced public patient admissions, and a new form of community rating was introduced taking more account of the different costs of people at different ages. While the respective roles of Medicare and Private Health Insurance remain matters of political controversy, along with the level and design of any subsidy, no serious question has been raised for more than 50 years about the Commonwealth having responsibility for regulating the Private Health Insurance industry and providing any support.

A final area of debate has been about regulation of the providers of health services. Until recently, this has remained largely with the States. During the last 20 years there has been a significant increase in Commonwealth involvement. Some Commonwealth involvement in residential aged care has been exercised by the conditions for financial support but, even in this area, a major extension of the Commonwealth role took place in the late 1990s with the establishment of the Aged Care Standards and Accreditation Agency. While the States retain the legal authority for accrediting hospitals, there has been a strong shift towards a national approach. Health workforce regulation has become increasingly national also, with more recent in-principle agreements for the Commonwealth taking responsibility.

In summary, the Commonwealth is the dominant government funder of health and aged care services, and has been for more than 50 years. It is not directly in the business of service provision, but it is by no means a passive funder simply reimbursing costs. It is increasingly a sophisticated purchaser of services, setting standards and influencing the distribution of services as well as promoting efficiency and cost-effectiveness. It has also long been involved in health industry regulation, and that role is currently expanding as the industry itself is becoming more national.

The case for a further and substantial increase in the Commonwealth role is based primarily on the changing demand for health services, and the obstacles which current divided responsibilities present to ensuring the most appropriate care for patients and the most efficient and effective use of taxpayer resources.

The changing demand for health services does not reflect growing health problems so much as the downside impact of our success.

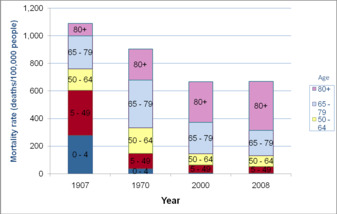

Figure 2: Australian Mortality Rates by Age3

Life expectancy in Australia is one of the highest in the world, and is continuing to rise. Between 1907 and 1970, this rise was driven mostly by reductions in mortality rates amongst younger people: many more Australians were living to age 50. Since 1970, life expectancy has continued to rise, but this improvement primarily occurs because those who reach age 50 live much longer afterwards. This trend is clearly continuing in the twenty-first century. It may be that Figure 2 will need to be re-drawn in a decade or so to separate mortality rates for those aged 80 to 89 from the rate for those over 90, with possible reductions in rates for those “young” people in their eighties!

What this means is that the health system is now responding to many more frail aged than ever before, and many more with chronic illnesses. More than 80 per cent of the burden of disease is now from chronic illness, mostly amongst the elderly, but also from mental illness and life-style causes. Most of the people concerned can live with a considerable degree of comfort and independence, but they need continuing support services: occasional acute care, drugs which lower their risks and reduce their pain, frequent diagnostic tests and check-ups, various allied health services and possibly personal care services including through residential aged care.

The Australian health system is particularly badly designed to respond to this change. Not only is it structured around programs of different providers (for example, hospitals, doctors, aged care homes and hostels) rather than around patients, but the boundaries are reinforced by having different government funders. The problems involved are not trivial. Rehabilitation services were wound back substantially during the 1990s leaving too much burden on families and/or forcing too many people into residential care.

On the other hand, limited places in residential aged care are still leaving many frail elderly in hospitals rather than in facilities better suited to providing continuing care and support. Emergency departments are clogged with people who really ought to see a general practitioner, and they wait for hours because the triage system rightly says they are not a priority. Patients are discharged without proper consultation with general practitioners and specialists and without proper post-operative care plans. Insufficient investments are being made into targeted prevention services such as diagnostic testing of at-risk population groups. Too many people in nursing homes are being sent to hospitals for services that could and should be provided in their homes. Too many people are dying in hospitals rather than with dignity in the comfort of their homes with their families.

There is no magic answer to these problems. The current approach of different programs funded by different governments is clearly exacerbating the situation. Incentives for the most appropriate and cost effective care are missing. Indeed, when health spending next comes under serious scrutiny, which must be soon, the incentives for service providers will once again be to focus on each one’s care responsibilities and to rely on others to fill the gaps.

The other shift in demand which the current health system is struggling to manage is the increase in community expectations for personalised services and choice. This shift requires quite fundamental micro-economic reform, with less emphasis on supply-side controls and more on the demand-side, and greater use of “internal markets” which provide the flexibility to respond to individual preferences without adding to total costs to taxpayers.

Examples of obstacles to micro-economic reform include the lack of an even-playing field for public or private hospital patients. Casemix funding might go some way to resolving the problem, but not the full distance. There is nothing more confusing for the public at the present time than whether to “go public or go private” when admitted to a public hospital. For public hospitals not funded according to numbers of patient episodes, (but by block funds based on estimates drawn from past history), a public patient is a cost without any compensating income; a private patient is a source of income but whose cost can be absorbed by adjusting queues. There is little or no incentive for a public hospital to compete for a contract with a Private Health Insurance fund for private patients as the default payment is generally sufficient, particularly when capital costs are met elsewhere. For the patient, having reached the point of admission, there is no queue-jumping advantage from “going private,” only the possibility of choice of doctor and access to a private room (depending on the insurance cover); on the other hand, there is still the likelihood of co-payments that a public patient does not face, notwithstanding improvements during the past ten years in funds reaching agreements with doctors and hospitals on “no or known” co-payments. As far as the Private Health Insurance funds are concerned, members “going public” relieve them of an expense, and encourages them to design products with high front-end deductibles intended precisely to cost-shift to public hospitals and hence to government and taxpayers.

It seems impossible to sort out this muddle while there are different government funders and different purchasing regimes, as well as fundamental flaws in the regulation and subsidies for private health insurance.

Micro-economic reform is also made more difficult when each health program has its own approach to co-payments, most of which are crude and not well-designed to balance the need to manage moral hazard and the need to allow reasonable access to appropriate services. A patient-focussed regime is far more likely to get the balance right.

More generally, the current program focus is almost certainly allocating resources inefficiently as well as inequitably. It is hard to believe that the separate budget arrangements for each program equates to the optimal balance of funds for the most cost-effective mix of services for individuals. There is growing evidence of excessive resources for hospitals and inadequate investment in primary and preventive services, including community support services for the aged and mentally ill. There is also evidence of the limitations of Medical Benefits Scheme/Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme arrangements for ensuring primary care support for people in rural and Indigenous communities in particular, but there is understandable reluctance by the States to make up the difference.

All this points to the need for a health system with the following design principles:

Table 2: Optimal System Design Principles

|

• National framework but with flexibility at a lower level.

• Mixed public and private system:

o governments concentrate on regulating, funding and

purchasing;

o service provision primarily private or charitable;

o increased competition amongst providers, increased

sophistication amongst purchasers;

o substantial role for private health insurance;

o significant role for co-payments and private

contributions.

• Single funder and/or single purchaser, with funds following

patients rather than being defined by strict functional or jurisdictional

boundaries.

• More emphasis on primary care support, including continuity of care

for those needing ongoing services across the system,

and increased investment

in preventive health.

|

The key options to help us move in this direction are:

A. States to have full responsibility for public purchasing of all health and aged care services.

B. The Commonwealth to take full financial responsibility as both public funder and public purchaser.

C. Commonwealth/State pooling with State or regional purchasers buying the full range of health and aged care services for the population involved.

D. Managed competition (Scotton model4 or NHHRC’s “Medicare Select”5).

Option A could follow Canadian practice with national principles set out in Commonwealth legislation together with a suitable revenue-sharing agreement. Spain also has a provincial-based system but reliant on national government funding. The question is, could such a system work in Australia given our history and our approach to health and health insurance? What would we actually do about the Medical Benefits Scheme and the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme, or the system of legislated entitlements for aged care services? Could or should we reverse the trend towards national approaches to industry regulation? What about private health insurance (the Canadians have effectively banned a substantial role for private health insurance under their “Medicare principles”)? Whatever the theorists might say about the benefits of subsidiarity, it is hard to see that this option is either politically feasible or economically sensible given our history and the current operational design of our system.

Leaving aside Option B for the moment, pooling along the lines of Option C was canvassed in some detail in the deliberations of the Council of Australian Governments in the 1990s. In theory, multiple government funders pooling their resources and using a single purchaser structure would achieve all the benefits of a single government funder as there would be no incentive to shift costs between funders or between programs. All costs and gains at the margin would be shared. The practical problems, however, proved to be immense: how to agree on the risk-sharing, how to agree on the policy framework, how to agree on the structure for purchasing and its accountability framework? The Howard Government in 1996 agreed to test the idea in one area. It chose aged care which does not have the demand-driven design challenges of the Medical Benefits Scheme or the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme. But even this idea was rejected out of hand by every State and territory. Discussion did not even reach first base. Moreover, pooling arrangements with shared responsibilities present other major practical problems including highly bureaucratic processes, delays in decision-making, and limited scrutiny of administration by legislatures.

Option D has some important attractions and could draw on the Netherlands’ experience and some experience in the United States. It involves identifying each individual’s risk-rated Medicare premium and paying that to the health insurance fund or healthcare manager chosen by the individual. These funds and managers would then compete for business, and would have incentives to optimise the healthcare of their members through the most cost-effective means they can find. The funds could also choose to offer additional benefits for members willing to pay for them. Accordingly, the option has the theoretical benefits of more choice and increased competition while still offering universal coverage.

Option D is, at best, “unproven”. The World Bank notes there are significant benefits from competing providers but limited, if any, gains from competing insurers. Private insurers may not be as effective in managing moral hazard as governments, and policing them to ensure they are, indeed, meeting their Medicare responsibilities and not avoiding risks by adverse selection techniques, etc, is not straightforward. Possibly more to the point right now is that to identify and pay risk-rated Medicare premiums requires a government to appropriate the funds. In Australia, this could only be done by the Commonwealth. Those attracted to this option need to identify a pathway to its implementation, a pathway which must involve the Commonwealth taking full financial responsibility.

This, in my view, leaves us with Option B, the Commonwealth as single government funder and purchaser. This would not rule out a later move to the Option D.

Option B requires the Commonwealth to be both funder and purchaser. The challenge of managing moral hazard requires increasing sophistication in purchasing, using a mix of fee for service or activity-based-funding, and funding based on populations and outcomes. Equity also demands pro-active purchasing, for example, to ensure services are available in rural and remote areas and for marginal groups.

Being essentially a monopsony purchaser, the Commonwealth also needs to develop a regulatory framework for setting prices within policies set by politicians. To take full advantage of being a single funder, the Commonwealth should also establish the capacity to analyse the health and financial risks of different population groups to develop strategies for most cost-effective support, complementing existing program-based strategies for determining cost-effective products and services.

There is little if any need for the Commonwealth to be involved in direct service provision. Indeed, the separation of purchasing from providing offers substantial benefits in terms of the professional independence of providers and the promotion of innovation, as well as greater efficiency through competition. But purchasing needs to be at a far more local level than nationally if there are to be improvements in allocational efficiency. While some national prices may be appropriate (for casemix, MBS, PBS, aged care entitlements), a considerable degree of flexibility about the quantum and mix of services, and to allow for variations in demand and supply, will be needed at a sub-national level (and, in most cases, at a sub-State or regional level).

Such a purchasing regime should not operate unilaterally. Owners of assets and managers of services should have some input into the policy framework, and access to some mechanism to review decisions taken by the price regulators.

This suggests some continuing roles for the States notwithstanding the Commonwealth being the sole funder and purchaser. These include contributing to the policy framework, particularly for the price regulators, through COAG or one of its ministerial councils. States should also take the lead on place management including the definition of regions and localities. Assuming the Commonwealth establishes some regional planning and purchasing structure, States and/or local government should be involved to help ensure appropriate placement of services.

States are likely to remain the owner of many major assets, and responsible for their governance. They may choose to transfer some of this role to local government or even community and not-for-profit organisations such as churches and charities. As such, they also need to have access to processes for review of pricing decisions by the Commonwealth regulators.

It is also possible to leave room for a State to choose to supplement the Commonwealth funding to meet perceived demands from their electors that are not being met by the Commonwealth. There would be dangers, however, of the Commonwealth cost-shifting its responsibilities in the future and opening up new boundary problems.

Current arrangements involve serious and increasingly important structural impediments to best and most cost-effective health care. The Commonwealth as the single government funder and purchaser would not automatically improve the system, but it is essential to future improvements and micro-economic reform.

Endnotes

1. AIHW; and Podger 1979.

2. Beddie 2001.

3. AIHW 2006, 2010.

4. Scotton 1994.

5. National Health and Hospitals Reform Commission 2009.

References

Australian Institute of Health, Australian Health Expenditure 1970-71 to 1984-85, AGPS, 1988.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Health Expenditure Bulletin, No. 17, September, 2001.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Mortality over the twentieth century in Australia, 2006.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Australia’s Health, 2010.

Francesca Beddie, Putting Life into Years: The Commonwealth’s Role in Australia’s Health Since 1901, Commonwealth of Australia, 2001.

National Health and Hospitals Reform Commission, A National Health and Hospitals Network for Australia’s Future, Australian Government, 2010, Canberra.

A.S. Podger, 1979, “Expenditures on Social Welfare in Australia, 1900-1970”, in Ronald Mendelsohn (ed), The Condition of the People, George Allen and Unwin, 1979.

A.S. Podger, 2006, ‘Directions for Health Reform in Australia’, in Productivity Commission, Productive Federalism, Proceedings of a Roundtable, February 2006.

A.S. Podger, “A Model Health System for Australia”, The Inaugural Menzies Centre Lecture on Public Health Policy, the Menzies Centre for Public Health Policy, 3 February 2006, published as a series of articles in the Asia Pacific Journal of Health Management, Volume 1, 1 and 2; and Vol 2, 1, 2006.

Richard Scotton, “The Scotton Model”, in Productivity Commission, Managed Competition in Health Care, Workshop Proceedings, 2002.

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/SGSocUphAUCon/2010/4.html