|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

Upholding the Australian Constitution: The Samuel Griffith Society Proceedings |

In the matter of seeking amendments to the Australian Constitution we can, I think, divide the 20th Century into two parts, namely the first three-quarters with one pattern and the last one-quarter with a different pattern. That is a rough division of time, but it illustrates the point explained below. With the sole exception of the republic question, the Prime Minister of the day has promoted an affirmative vote. Therefore, by looking at the record of referendums, we can see what has motivated the leaders of our federal governments.

Consider the (chronologically) first 28 proposals placed before the people. This period begins with the first proposal put (Senate Elections in December, 1906) and concludes with the 27th (Prices) and the 28th (Incomes), polled on the same day in December, 1973. Of those 28, no less than 23 proposed to amend s.51 of the Constitution, which sets out the concurrent powers of the Commonwealth Parliament. In short, the Prime Ministers of that period were overwhelmingly motivated by a desire to increase the powers of the Commonwealth.

Now consider questions 29 through to 44 (a total of 16), for which referendums were held between May, 1974 and November, 1999. Not a single one of those sought to amend s.51. The priorities of our Prime Ministers had changed. What, then, were those priorities for the last quarter of the 20th Century when attention was given to constitutional change? One would have to concede they were more mixed than for the earlier period. Yet one item on the agenda of Prime Ministers stands out. All five men – Gough Whitlam (1972-75), Malcolm Fraser (1975-83), Bob Hawke (1983-91), Paul Keating (1991-96) and John Howard since 1996 – have proved themselves to be Senate bashers.

These five men were all significant holders of the office of Australian Prime Minister. Consequently their records can be checked. In the case of Whitlam, the Senate-bashing aspect of the man is so well established it scarcely needs to be re-stated. Nevertheless, I discuss below two aspects which have tended to be over-looked. In the case of Howard, this part of his agenda did not become clear until June last year, when he made a speech to the Liberal Party’s National Convention in Adelaide. It is to that part of Howard’s record this paper is mainly devoted. His record, however, should be seen in the context of his predecessors – Whitlam, Fraser, Hawke and Keating.

Gough Whitlam was a member of, in fact he was the leading light of, the Joint Committee on Constitutional Review established by the Commonwealth Parliament during the 1950s. Its 1959 Report came to 173 pages (not including Appendices) and was much praised by the progressives of the day. Yet its historical status is one of failure – a discredited, disreputable report which succeeded in achieving only one amendment, the repeal in 1967 of the old s.127 of the Constitution. In other words, only three of its 173 pages have been put into effect, pages 54, 55 and 56, or Chapter 9 “Reckoning of Population”. What a dismal record! It was disparaged by both Sir Robert Menzies and Sir Garfield Barwick who, as Prime Minister and Attorney-General respectively, had carriage of constitutional reform. A powerful dissenting report was delivered by Senator Reginald Wright (Liberal, Tasmania) as Appendix B, constituting pages 176-188.

Chapter 5 was titled “Terms of Senators” and covered pages 34-38. Here was set out the most dishonest proposal to amend the Constitution ever put to the people in my lifetime. Under the title Constitution Alteration (Simultaneous Elections) 1974 it was first put to the people at a May, 1974 referendum by the Whitlam Government. Purporting to provide for simultaneous elections for the two Houses, its real purpose was to give the Prime Minister more power over the Senate. By doing away with the current senatorial fixed term of six years and replacing that with two terms of the House of Representatives, it would have given the Prime Minister the power at any time to dissolve half the Senate by virtue of his power to dissolve the House of Representatives.

Each of Whitlam’s two successors tried to implement this same proposal without success, at referendums in May, 1977 and December, 1984, respectively. The only difference lay in the title. For the Fraser Government the title was Constitution Alteration (Simultaneous Elections) 1977, while for the Hawke Government it was Constitution Alteration (Terms of Senators) 1984. My case rests upon this notable similarity. Each of Whitlam, Fraser and Hawke were Senate bashers.

Paul Keating never actually caused a referendum to take place. Had he been given the power to do so he would surely have given priority to promoting the republic. My claim that he was a Senate basher lies in the simple fact that, speaking in Parliament as Prime Minister in November, 1992, he coined the memorable phrase “unrepresentative swill” to describe the Senate. I have more to say on that below.

I now come to John Howard. From 1996 to 2002 he seemed willing enough to negotiate his legislative programme through the Senate without making too many concessions to influential Senators whose votes he needed. However, on 8 June, 2003 he gave his closing address to the Liberal Party’s National Convention in Adelaide. The transcript of that speech reads in part as follows:

“We all know from our learning of Australian history that the Senate was essentially given its powers as a result of the federal compact between the various States of Australia at the time of Federation. The ideal was that it would be a State’s house as well as a house of review. The reality is that long years ago the federal Senate ceased to be a State’s house, and in more recent times it has certainly also dropped the pretence of being a house of review. Tragically for Australia, through the instrument of the Labor Party and the minor parties, the Australian Senate in recent years, so far from being a State’s house or a house of review, has become a house of obstruction. . .

“The deadlock provisions of the Constitution in section 57 were inserted way back at the time of Federation. And they contemplated the holding of a joint sitting after a double dissolution election in order to resolve deadlocks between the two Houses. The reality is that in a period of 102 years they have only been used to produce a joint sitting on one occasion and that was in 1974. . . .

“And not surprisingly, when you look back through the history of constitutional examination you find some nuggets, and I found a nugget back in 1959. It was a Joint Parliamentary Committee on Constitutional Reform and it had impeccable bipartisan credentials. One member of it was the then member for Werriwa, Edward Gough Whitlam, and another was Sir Alec Downer. . . And what that Committee essentially recommended was that the Constitution should be altered by referendum to provide that if legislation were rejected on a number of occasions by the Senate in the way described in section 57, there could be a joint sitting of the two Houses called without the necessity to hold a double dissolution election: and that if the legislation were passed through that joint sitting then it would become law. I think that could offer, some years into the future, a way of providing a more modern and contemporary and workable method of resolving differences between the two Houses”.

Howard’s description of that Report is good for a chuckle from anyone acquainted with its politics. At the time, Labor chose to give its allotted places to its heavyweight Members and Senators, Arthur Calwell, Gough Whitlam, Reg Pollard and Eddie Ward from the House and Nick McKenna and Pat Kennelly from the Senate. By contrast, the Liberals chose (apart from the dissenting Reg Wright) those among its members of lightest weight. In truth Sir Alec Downer was a less substantial figure than his son! Howard’s description that the Report had “impeccable bipartisan credentials” would have been greeted with a hollow laugh by senior members of the Liberal Party at the time.

With that June, 2003 Adelaide speech Howard placed himself firmly in the line of Senate-bashing Prime Ministers, with Whitlam, Fraser, Hawke, Keating and Howard competing for the title of the man most willing to assert the supremacy of the House of Representatives over the Senate. More, however, was to come. As promised in that speech, the Howard Government would release in October, 2003 its official paper with the title Resolving Deadlocks: A Discussion Paper on Section 57 of the Australian Constitution.

Now for a brief diversion. My paper contains eight tables, and it is no accident that they are updated versions of the same eight tables which appeared in my chapter Thoughts on the 1949 Reform of the Senate, in the Proceedings of the Eleventh Conference of this Society held at Melbourne in July, 1999.1 My theme today is exactly the same as was my theme then. So permit me to quote myself:

“The 1949 reform was the result of a piece of ordinary legislation which passed through the Commonwealth Parliament in 1948. At the time debate was dominated by the short-term consequences of the new system. Looking back over 50 years, however, we can now give a verdict on the behaviour of the Senate. It is given in Table 1. Note that there have now been more parliaments under ‘PR’ than there were under previous non-proportional systems from 1901 to the election of the 18th Parliament in 1946”.2

|

Date of Electiona

|

Number of Parliament

|

Prime Minister at Opening

|

Date of Dissolution

|

|

Hostile Senateb

|

|

|

|

|

December 1949

|

19

|

Menzies (Liberal)

|

March 1951

|

|

December 1972

|

28

|

Whitlam (Labor)

|

April 1974

|

|

May 1974

|

29

|

Whitlam (Labor)

|

November 1975

|

|

October 1980

|

32

|

Fraser (Liberal)

|

February 1983

|

|

December 1984

|

34

|

Hawke (Labor)

|

June 1987

|

|

Government Senate Majority

|

|

|

|

|

April 1951

|

20

|

Menzies (Liberal)

|

April 1954

|

|

May 1954

|

21

|

Menzies (Liberal)

|

November 1955

|

|

November 1958

|

23

|

Menzies (Liberal)

|

November 1961

|

|

December 1975

|

30

|

Fraser (Liberal)

|

November 1977

|

|

December 1977

|

31

|

Fraser (Liberal)

|

September 1980

|

|

Government de Facto Senate Control

|

|

||

|

December 1955

|

22

|

Menzies (Liberal)

|

October 1958

|

|

December 1961

|

24

|

Menzies (Liberal)

|

November 1963

|

|

November 1963

|

25

|

Menzies (Liberal)

|

October 1966

|

|

November 1966

|

26

|

Holt (Liberal)

|

September 1969

|

|

October 1969

|

27

|

Gorton (Liberal)

|

November 1972

|

|

March 1983

|

33

|

Hawke (Labor)

|

October 1984

|

|

July 1987

|

35

|

Hawke (Labor)

|

February 1990

|

|

March 1990

|

36

|

Hawke (Labor)

|

February 1993

|

|

March 1993

|

37

|

Keating (Labor)

|

January 1996

|

|

March 1996

|

38

|

Howard (Liberal)

|

August 1998

|

|

October 1998

|

39

|

Howard (Liberal)

|

October 2001

|

a The date of the election is that for the House of Representatives, which was also usually a Senate election date. The government of the day at all times enjoyed a House of Representatives majority and, therefore, total control of the Lower House.

b A “Hostile Senate” is defined as one which was dissolved. Thus the Date of Dissolution column records the date of the double dissolution. In respect of rows for “Government Senate Majority” and “Government de Facto Senate Control” the dissolution date is for the House of Representatives only. It is important to note that there were only five double dissolutions but there were 16 dissolutions for the Lower House alone. Those 16 dissolutions produced five general elections for the House of Representatives only (1954, 1963, 1966, 1969 and 1972) and 11 House of Representatives plus half-Senate elections.

And “PR” means proportional representation. It was placed in inverted commas to recognize that the international literature on electoral systems calls our Senate system “semi-proportional” because of the malapportionment between the States, each always having the same number of Senators for very different population sizes. At the Census of March, 1901 the population of New South Wales was 1,354,800, that of Western Australia 184,100 and of Tasmania 172,500. At the August, 2001 Census the population of New South Wales was 6,371,700, that of Western Australia 1,851,300 and of Tasmania 456,700.

It can be ascertained that only five of the 21 Parliaments in Table 1 saw the government of the day with a Senate majority. Where I differ from Howard’s paper lies in my explanation for the rarity of that. The contrast between the two explanations could scarcely be greater.

Consider, first, the Howard paper’s description on pages 5 and 6:

“Today, there is a case for change. Two important legislative reforms have combined to alter the composition and function of the Senate fundamentally.

“First, the introduction of proportional representation in 1948, taking effect in 1949, has fostered the development of minor parties.

“This has been a valuable evolution in the representative character of the Australian Parliament.

“In addition to the introduction of proportional representation, there was an amendment in 1983 which increased the number of Senators elected in each State from five to six at a half-Senate election.

“In practice, the election of an even number of Senators at a half-Senate election, combined with proportional representation, has meant that it is virtually impossible for a government to obtain a majority in the upper house, no matter how large its majority is in the lower house”.

Then on page 29 the discussion paper remarks:

“Critically, the increase to 12 Senators means that at each election there will be six, not five Senate spots available in each State.

“Therefore it is much more difficult statistically for a political party to win a majority of Senate seats from an even number at each half-Senate election than the odd number that existed before the amendment was made in 1983.

“When there were 10 Senators from each State, a party at a half-Senate election could win a majority of seats in a particular State (i.e., three out of five) with 50.01 per cent of the vote in that State.

“However, now with 12 Senators, a party needs 57.16 per cent of the vote at a half-Senate election to win a majority of seats in a State (four out of six)”.

If one were motivated to be extremely charitable to the discussion paper one could (perhaps) say that there is “something in” all that. The trouble is that the discussion paper does not explain why only the Menzies and Fraser governments were able to get Senate majorities. The inference that the reader is meant to draw is to say “Menzies and Fraser governed before the amendment of 1983”. The statement is true but is not central to the argument. The paper nowhere mentions the truly important trend – the declining shares of big party votes.

In a proportional representation system a government can fairly complain if it gets a majority of Senate votes, Australia-wide, but not a majority of seats in the Senate. Thus Menzies could fairly complain when the 1949 election gave him a majority of the votes for both Houses but Labor continued to have a Senate majority in seats. However, no Prime Minister post-Fraser can so complain. Table 2 sets out the percentages at those elections when a “big party” received a vote in excess of 49 per cent. I regard a 49 per cent support as high enough to be called a “majority” of the vote.

It will be noticed that two of the four entries in Table 2 failed to give a majority in the whole Senate to the party with the majority of votes. Labor continued to have a majority in the

Table 2: Senate first preference “majority” percentages

|

Party

|

1949

|

1951

|

1953

|

1975

|

|

Coalition

|

50.4

|

49.7

|

44.4

|

51.7

|

|

Labor

|

44.9

|

45.9

|

50.6

|

40.9

|

Senate in the Menzies 19th Parliament. By contrast, Menzies had a Senate majority throughout the whole of the 20th and 21st Parliaments – even though Labor won 50.6 per cent of the vote at the May, 1953 separate election for half the Senate. In all three cases the reason had to do with the rotation of Senators.

By contrast, the Coalition’s 49.7 per cent in 1951 and 51.7 per cent in 1975 did produce a Senate majority in the 20th, 21st, 30th and 31st Parliaments. The reason has to do with the proportionality of the result when the most recent election was double dissolution, and the semi-proportionality of the result when the most recent election was half-Senate. I have more to say on that below, where I shall give a detailed explanation as to why Menzies and Fraser enjoyed the Senate majority which has wholly eluded the Howard Government.

The continuing refusal of the Australian people to vote for the government of the day in the Senate election has produced this consequence. The normal situation is that the government has de facto control of the Senate without enjoying an actual majority. While we may disagree, on the merits of each particular case, with the decision of the Senate to reject this or that piece of government legislation, it is difficult to object on democratic grounds.

In defence of my view I set out in Table 3 the percentage of the vote secured by the Government (which in 1983 and 1996 entered the election as the Opposition party) at the Senate election relevant to the main life of that Parliament. Note that in 1964, 1967 and 1970 the election in question was a separate election for half the Senate.

Table 3: Selected Government Senate percentages

(Parliaments where Government had de facto Senate control)

|

Election Date

|

Party

|

Percentage

|

|

December 1955

|

Coalition

|

48.7

|

|

December 1961

|

Coalition

|

42.1

|

|

December 1964

|

Coalition

|

45.7

|

|

November 1967

|

Coalition

|

42.8

|

|

November 1970

|

Coalition

|

38.2

|

|

March 1983

|

Labor

|

45.5

|

|

July 1987

|

Labor

|

42.8

|

|

March 1990

|

Labor

|

38.4

|

|

March 1993

|

Labor

|

43.5

|

|

March 1996

|

Coalition

|

44.0

|

|

October 1998

|

Coalition

|

37.7

|

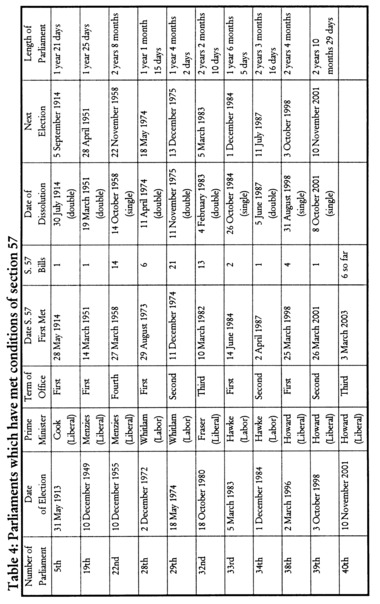

While a Government may, perhaps, reasonably object to Senate rejection of its legislation by a genuinely hostile Senate (of which there have been only five cases in 21 Parliaments after 1949), it is difficult to see how any Government could reasonably object to Senate rejection of legislation during any of the Parliaments covered by Table 3. It is worthwhile noting that four of the Parliaments contained in Table 3 met the technical conditions of s.57 of the Constitution – as is set out in Table 4. It is also worth noting that none of Menzies, Hawke or Howard could justify to himself or his party the pulling of the “triggers” he had established for himself in the 22nd, 33rd, 38th and 39th Parliaments. That is why the subsequent election was of the conventional type, that is to say for the House of Representatives and half the Senate.

The discussion paper trades on the ignorance of readers in matters psephological. Take, for example, the assertion “that it is virtually impossible for a government to obtain a majority in the upper house, no matter how large its majority is in the lower house”.4 The reader is encouraged to assume that a large majority in the Lower House is based on a high share of the vote. Such is usually not the case – as can be seen by considering the example of the March, 1996 election, Howard’s first win. In the House of Representatives vote the Coalition received 47 per cent of first preferences, which inflated to 54 per cent of the two-party preferred vote, which inflated to 64 per cent of the seats. In the Senate election, however, the Coalition received only 44 per cent (see Table 3). Could anyone seriously argue that there was an injustice to the Coalition that it lacked a Senate majority in Howard’s first term?

Readers who compare this paper with my earlier paper for the Eleventh Conference of this Society may notice that I have updated Table 1 and Table 3 each by one parliamentary term, but I have updated Table 4 by two terms. The reason for the apparent discrepancy is that the history books have not yet determined whether or not the present (40th) Parliament ended up as a “hostile Senate” case. Personally I have no doubt there will not be a double dissolution. If I am right, then the 22nd Parliament (the fourth Menzies term) and the 40th (the third Howard term) will rival each other for the number and importance of “triggers” never pulled. As can be seen from this, I do not accept that the present can be described as a “hostile Senate”. That becomes so only if the Prime Minister makes it so. He could do that by double dissolving.

There are very good reasons why I compare and contrast the comparable 22nd and 40th Parliaments. The two similarities are: (a) no double dissolution, notwithstanding the number and importance of “triggers”; and (b) a reasonable expectation of a Coalition gain in Senate seats at a half-Senate election. The three dissimilarities are: (a) five-seat Senate elections in 1958 but six-seat Senate elections in 2004; (b) the Menzies prospect to get an actual Senate majority in 1958 contrasting with Howard’s chance to get “only” 38 out of 76 senators in 2004; and (c) the much higher Coalition Senate vote under Menzies than under Howard.

Point (c) above needs to be repeated and stressed. Whenever one compares like with like under each of Menzies, Fraser and Howard, one finds the Coalition’s Senate percentages to be highest under Menzies, second highest under Fraser and lowest under Howard. Here we have the first example. When Menzies decided not to double dissolve in 1958, he was aware that the Coalition’s Senate vote had been 44.4 per cent in 1953 and 48.7 per cent in 1955, an average of 46.6 per cent. However, when Howard decides not to double dissolve in 2004, he will be aware that the Coalition’s Senate vote has been 37.7 per cent in 1998 and 41.8 per

cent in 2001, an average of 39.8 per cent.

The creation of six-seat half-Senate elections under Howard (compared with five-seaters under Menzies and Fraser) was implemented by the Hawke Government in 1983. To get the numbers in the Senate, Labor persuaded the National Party to go along with its plan, which was opposed by the Liberal Party and the Democrats. That fact has enabled the Liberals to make a claim to the moral high ground which, on the face of it, seems reasonable. They can then proceed to claim that the Hawke Government wrecked the Coalition’s position in the Senate. They can even do something which Howard actually did in his June, 2003 Adelaide speech quoted at length above. As part of that speech he said:

“As a result of the changes that were made in 1983 when the size of the Parliament was increased, I might remind you against the determined vote of the Liberal Party, it is for practical purposes impossible for the Coalition in its own right to obtain a majority of the 76 members of the federal Senate”.

It is quite wrong to make that “impossible for the Coalition” claim. Howard could double dissolve in 2004 and could easily get a Senate majority if the Coalition’s Senate vote were high enough. It has been demonstrated in Table 2 that the Menzies Senate vote of 49.7 per cent at the 1951 double dissolution election was enough to give him a Senate majority. The Fraser Senate vote of 51.7 per cent at the 1975 double dissolution election was also enough to give him a Senate majority. With 12 Senators per State to be elected today (instead of 10 then) it would be even easier for Howard – provided that the Coalition’s Senate share were high enough.

Howard must surely know that this “impossible for the Coalition” claim is nonsense. The truth was stated above: whenever one compares like with like under each of Menzies, Fraser and Howard, one finds the Coalition’s Senate percentages to be highest under Menzies, second highest under Fraser and lowest under Howard. Surely the Liberal Party must know that.

This point is one of two reasons why I quoted Howard as I did immediately above. The other reason is to note his words “against the determined vote of the Liberal Party”. That is a correct statement of history, but the reality is that the Nationals at the time understood the future electoral interests of the Coalition better than did the Liberals.

This assertion, the truth of which I demonstrate below, explains why I describe the Howard discussion paper as I do, namely as “a dishonest piece of current Liberal Party propaganda”. Never do I use the expression “Coalition propaganda”. The reason is that I do not associate the National Party with it.

Conversations I have had with senior Nationals leave me in no doubt about three key points. First, none of them really supports the paper. Second, they are very much aware that these six-seat half-Senate elections would never have come about but for the parliamentary votes of the Labor and National parties combining to give the plan (to increase the Parliament’s size) a Senate majority in a circumstance where both the Liberals and Democrats were opposed. Third, the Nationals are well aware that in 1983 their parliamentarians did, indeed, understand the future electoral interests of the Coalition better than did the Liberals.

To demonstrate the truth of this assertion I begin with the Senate as it was composed from July, 1993. There is a good reason for that. The first Senate election under the increase (in December, 1984) was for seven Senators per State as a transition to the higher number. The second (in July, 1987) was a double dissolution. Thus the third and fourth elections (in March, 1990 and March, 1993) were the first cases of six-seat Senate elections. The state of Senate parties from July, 1993, therefore, constituted the first case where the numbers were composed from the combination of two preceding six-seat half-Senate elections. When I use the expression “37th Parliament” I refer to Senate numbers from 1 July, 1993. Consequently the Senate numbers for the 38th, 39th and 40th Parliaments mean from 1 July, 1996, 1999 and 2002 respectively.

In the 37th Parliament the Coalition had 36 of the 76 Senators (or 47.4 per cent), yet its March, 1993 Senate vote was only 43 per cent. In the 38th Parliament the Coalition had 37 of the 76 Senators (or 48.7 per cent) yet its March, 1996 Senate vote was only 44 per cent. In the 39th Parliament the Coalition had 35 of the 76 Senators (or 46 per cent) yet its October, 1998 Senate vote was only 37.7 per cent. In the present (40th) Parliament the Coalition has 35 of the 76 Senators (or 46 per cent), yet its November, 2001 Senate vote was only 41.8 per cent. It is clear, therefore, that from 1993 onwards so-called “proportional representation” has disproportionally favoured the Coalition, albeit at a lower rate than the “one vote, one value” House of Representatives.

It will be noticed that the number of Coalition Senators (35) is the same now as it was in the last (39th) Parliament. The reason for that is simply explained. In March, 1996 the Coalition won 20 of the 40 places (three out of six in each of six States and one out of two in both Territories) and exactly the same occurred in November, 2001. Bearing in mind that the Coalition scored a 50 per cent success rate both times in seats, one can have little sympathy for Coalition complaints when one also notices their shares of the vote: only 44 per cent in 1996 and 41.8 per cent in 2001.

The 35 present Coalition Senators are four short of a majority, which is 39 out of 76. A notional re-count of the 1998 and 2001 Senate votes into five-seat elections shows the Coalition the same four seats short of a majority as at present, but without Senators Brian Harradine, Len Harris or Meg Lees to negotiate with. The balance of power would instead be shared between three Greens and six Democrats. So, instead of being disadvantaged, the Howard Government holds eight of the additional 16 seats in the Senate expanded since the Menzies era, while Labor has only five. The essential reason for this is the ease with which the Coalition can win three places out of six in each State and one out of two in each Territory.

If I am right in my prediction that the next election will again be for half the Senate, then it is safe to assume there will be 37 Coalition Senators – as there were in the 38th Parliament, Howard’s first term. Should Brian Harradine retire, then the Coalition would have 38 Senators, or 50 per cent of the seats, for a likely 42 per cent of the vote.

Essentially what I have been doing above has been measuring deviations from proportionality in translating votes into seats. These are questions vital to understand the distribution of political power. They are not mere academic questions. Yet they do raise two interesting questions for the academic. First, when does an election result cease to be proportional and become semi-proportional? Second, when does an election result cease to be semi-proportional and become non-proportional? The answer lies in a device of modern psephology known as the Gallagher least squares index of disproportionality. Named after the Irish political scientist Michael Gallagher, it measures in a single statistic deviations from proportionality.

In respect of recent events studied by me the highest index was that for the November, 1993 New Zealand general election. The index was 17.69. That composite statistic was calculated from a National Party over-representation of 15.46 (50.51 per cent of seats for 35.05 per cent of votes), a Labour over-representation of 10.77, an Alliance under-representation of 16.19, a New Zealand First under-representation of 6.38, and so on.

South Africa has the most proportional system in the world today. At the June, 1999 general election the Gallagher least squares index of disproportionality was only 0.16. For example, the African National Congress won 266 of the 400 seats in the National Assembly, which is 66.50 per cent of the seats. It had 66.36 per cent of the votes. The New National Party won 28 seats, exactly seven per cent of the 400 seats. It won 6.87 per cent of the votes; and so on.

Table 5 gives the equivalent Australian figures. Double

dissolution elections are shown with the word “(full)” by their

|

Election

|

House of Representatives

|

Senate

|

|

1949

|

7.50

|

3.42

|

|

1951

|

5.36

|

3.03 (full)

|

|

1953

|

–

|

3.29

|

|

1954

|

2.88

|

–

|

|

1955

|

6.84

|

6.52

|

|

1958

|

11.05

|

6.18

|

|

1961

|

7.12

|

9.75

|

|

1963

|

9.00

|

–

|

|

1964

|

–

|

2.06

|

|

1966

|

10.83

|

–

|

|

1967

|

–

|

3.80

|

|

1969

|

6.95

|

–

|

|

1970

|

–

|

3.16

|

|

1972

|

6.90

|

–

|

|

1974

|

5.96

|

3.72 (full)

|

|

1975

|

14.05

|

3.08 (full)

|

|

1977

|

15.02

|

7.30

|

|

1980

|

8.46

|

1.51

|

|

1983

|

10.41

|

3.37 (full)

|

|

1984

|

7.82

|

5.35

|

|

1987

|

10.41

|

2.60 (full)

|

|

1990

|

12.49

|

4.39

|

|

1993

|

8.06

|

3.33

|

|

1996

|

11.24

|

4.54

|

|

1998

|

11.85

|

7.34

|

|

2001

|

9.81

|

8.47

|

side, indicating an election for the whole Senate. It should be noted that only in 1961 did the Senate election result turn out to be less proportional than that for the House of Representatives. It was a half-Senate election. My broad judgment is that an index of less than four constitutes a proportional result, while an index of more than ten constitutes a non-proportional result. Anything in between is semi-proportional. Thus I say that only when the whole Senate is elected can the system truly be said to be one of proportional representation. Notice that the index was 3.03 in 1951, 3.72 in 1974, 3.08 in 1975, 3.37 in 1983 and 2.60 in 1987.

While Table 5 may seem somewhat academic, it illustrates a point which by now must be very clear to the reader. A half-Senate poll in 2004 will yield a semi-proportional result favourable to the Coalition. It would also enable the Coalition to preserve in full the benefits of the 2001 half-Senate election result, which yielded a semi-proportional result very favourable to the Coalition. By contrast, a double dissolution will yield a proportional result. Given its very low vote these days, that is the last thing the Coalition is likely to want. In terms of Senate seats, it means Howard choosing to have 32 Senators following a double dissolution compared with 37 or 38 from July, 2005 following a half-Senate election.

There is, therefore, only one outcome from a double dissolution likely to be attractive to Howard, namely the joint sitting it offers whereby he can pass all the legislation being the present and any future “triggers”. That is what truly motivates the Coalition in its desire for “Senate reform”. Whereas the present Constitution offers such an opportunity only after a double dissolution, the Coalition would ideally want that after a normal half-Senate election. As will be explained below, Senate reform means allowing Howard (and every future Prime Minister) to have his cake and eat it too.

I made the remark above that “whenever one compares like with like under each of Menzies, Fraser and Howard, one finds the Coalition’s Senate percentages to be highest under Menzies, second highest under Fraser and lowest under Howard”, and I gave two examples of that. Let me now draw that comparison together by taking the first four elections of each as Prime Minister or incoming Prime Minister. If one takes the Senate percentages (from Table 7) for Menzies in 1949, 1951, 1953 and 1955, the average is 48.3 per cent. If one takes the percentages for Fraser in 1975, 1977, 1980 and 1983, the average is 45.2 per cent. If one predicts a Senate vote of 42 per cent for the Coalition in 2004, and then takes an average for Howard’s elections of 1996, 1998, 2001 and 2004, one finds the average is 41.3 per cent. It must by now be entirely clear that the Coalition has no basis to complain.

Tables 6 and 7 draw this all together. While Table 7 is self-explanatory, Table 6 needs some explaining. A “John Howard Prime Minister” is one who had been Leader of the Opposition but had led his party out of Opposition to victory at a general election. The Senate record of the five post-war cases is set out in Table 6. One notices the decline in their Senate percentages at their second wins. Most of all, however, I am impressed by the magnitude of the Howard decline, and the low overall vote, a miserable 37.7 per cent, in 1998. It is my confidence that the Coalition will get a better figure in 2004 that causes my prediction

|

Prime Minister

|

1st Win

|

Senate % at 1st Win

|

2nd Win

|

Senate % at 2nd Win

|

Decline

|

|

Robert Menzies

(Liberal)

|

December 1949

|

50.4

|

April 1951

|

49.7

|

0.7

|

|

Gough Whitlam (Labor)

|

December 1972

|

(a)

|

May 1974

|

47.3

|

—

|

|

Malcolm Fraser (Liberal)

|

December 1975

|

51.7

|

December 1977

|

45.6

|

6.1

|

|

Robert Hawke (Labor)

|

March 1983

|

45.5

|

December 1984

|

42.2

|

3.3

|

|

John Howard (Liberal)

|

March 1996

|

44.0

|

October 1998

|

37.7

|

6.3

|

(a) The December, 1972 election was for the House of Representatives only.

that there will be 37 or 38 Coalition Senators from July, 2005 following the 2004 election, which will be for half the Senate. I am quite confident of my predictions both of the type of Senate election and of the number of Coalition Senators.

I remarked above that “Senate reform means allowing Howard . . . . . to have his cake and eat it too”. In order to understand that assertion let me take the two options proposed in the discussion paper. Since the Coalition will choose to have its 37 or 38 senators (rather than 32) it will not get a joint sitting under the present Constitution, because no double dissolution will occur. However, both options would give the Howard Government the joint sitting in addition to their 37 or 38 Senators.

Option 1 is the “nugget” referred to by Howard in his speech to the Liberal Party’s National Convention in Adelaide. It was recommended by the parliamentary Committee in 1959 which, according to Howard, “had impeccable bipartisan credentials”. Option 2 is often referred to as the “Lavarch Model”, though its alleged author Michael Lavarch (Attorney-General from April, 1993 to March, 1996 in the Keating Government) denies being its sponsor.

|

Election

|

Vote %

|

Election

|

Vote %

|

|

1910

|

45.6

|

1949

|

50.4

|

|

1913

|

49.4

|

1951

|

49.7

|

|

1914

|

47.8

|

1953

|

44.4

|

|

1917

|

55.3

|

1955

|

48.7

|

|

1919

|

55.2

|

1958

|

45.2

|

|

1922

|

52.0

|

1961

|

42.1

|

|

1925

|

54.9

|

1964

|

45.7

|

|

1928

|

50.5

|

1967

|

42.8

|

|

1931 (highest)

|

55.4

|

1970

|

38.2

|

|

1934

|

53.2

|

1974

|

43.9

|

|

1937

|

44.8

|

1975 (highest)

|

51.7

|

|

1940

|

50.4

|

1977

|

45.6

|

|

1943 (lowest)

|

38.2

|

1980

|

43.5

|

|

1946

|

43.3

|

1983

|

39.9

|

|

|

|

1984

|

39.5

|

|

|

|

1987

|

42.0

|

|

|

|

1990

|

41.9

|

|

|

|

1993

|

43.0

|

|

|

|

1996

|

44.0

|

|

|

|

1998 (lowest)

|

37.7

|

|

|

|

2001

|

41.8

|

|

Average 1910–46

|

49.7

|

Average 1949–2001

|

43.9

|

Note: The term Non-Labor means Liberal from 1910 to 1914, Nationalist in 1917, Nationalist-CP from 1919 to 1928, UAP-CP from 1931 to 1943, Liberal-CP from 1946 to 1980 and Liberal-National since 1983.

Now let me reproduce the drafting of the proposed new s.57A (Option 1):6

“57A Disagreement between the Houses

(1) If:

(a) the House of Representatives passes any proposed law; and

(b) the Senate rejects or fails to pass it, or passes it with amendments to which the House of Representatives will not agree; and

(c) after an interval of three months the House of Representatives, in the same or the next session, again passes the proposed law with or without any amendments which have been made, suggested, or agreed to by the Senate; and

(d) the Senate rejects or fails to pass it, or passes it with amendments to which the House of Representatives will not agree;

the Governor-General may convene a joint sitting of the members of the Senate and of the House of Representatives. But such joint sitting shall not take place after the next dissolution of the House of Representatives.

(2) The members present at the joint sitting may deliberate and shall vote together upon the proposed law as last proposed by the House of Representatives, and upon amendments, if any, which have been made therein by one House and not agreed to by the other. Any such amendments which are affirmed by an absolute majority of the total number of the members of the Senate and House of Representatives shall be taken to have been carried.

(3) If the proposed law, with the amendments, if any, so carried, is affirmed by an absolute majority of the total number of the members of the Senate and House of Representatives, it shall be taken to have been duly passed by both Houses of the Parliament, and shall be presented to the Governor-General for the Queen’s assent”.

And now let me reproduce the drafting of the proposed new s.57A (Option 2):7

“57A Disagreement between the Houses

(1) If:

(a) the House of Representatives passes any proposed law; and

(b) the Senate rejects or fails to pass it, or passes it with amendments to which the House of Representatives will not agree; and

(c) after an interval of three months the House of Representatives, in the same or the next session, again passes the proposed law with or without any amendments which have been made, suggested, or agreed to by the Senate; and

(d) the Senate rejects or fails to pass it, or passes it with amendments to which the House of Representatives will not agree; and

(e) after a dissolution of the House of Representatives, the House of Representatives again passes the proposed law, with or without any amendments which have been made, suggested, or agreed to by the Senate; and

(f) the Senate rejects or fails to pass it, or passes it with amendments to which the House of Representatives will not agree;

the Governor-General may convene a joint sitting of the members of the Senate and of the House of Representatives.

(2) The members present at the joint sitting may deliberate and shall vote together upon the proposed law as last proposed by the House of Representatives, and upon amendments, if any, which have been made therein by one House and not agreed to by the other. Any such amendments which are affirmed by an absolute majority of the total number of the members of the Senate and House of Representatives shall be taken to have been carried.

(3) If the proposed law, with amendments, if any, so carried, is affirmed by an absolute majority of the total number of the members of the Senate and House of Representatives, it shall be taken to have been duly passed by both Houses of the Parliament, and shall be presented to the Governor-General for the Queen’s assent”.

Media commentators have been unanimous in expressing the assessment that Option 1 is more radical than Option 2. Consequently they have judged that Option 1 is quite out of the question whereas, perhaps, there may be some point in considering the merits of Option 2.

The discussion paper itself has a conclusion which lists various things it does not propose to do, and then asserts:

“What this paper does not accept is that there should be a permanent and absolute veto for minority interests.

“Until such time as there is a more workable and efficient means of resolving deadlocks, the effectiveness of Australian governments will be impaired.

“Perhaps more significantly, the will of the electorate will remain subject to a veto for which there is no practical resolution.

“The solution must be to develop a model which more faithfully reflects the will of the people and the intentions of those who drafted the Constitution.

“It is a proposal therefore deserving of careful consideration and a constructive public debate”.8

I expect that control-freak Prime Ministers would endorse the thoughts above. By contrast, I disagree with every sentence. I deny that the present s.57 gives a permanent and absolute veto for minority interests. Nor is it true to say that a century of operation of s.57 has impaired the effectiveness of Australian governments. It is absurd to assert that the will of the electorate is subject to a veto for which there is no practical resolution. Since there is no problem, there is no need for a solution. The proposals do not deserve consideration, because they constitute a further impairment of the bicameral system.

Option 1 effectively turns a bicameral Parliament into a unicameral one. My firm impression is that only two members of the current federal Parliament actually support it, John Howard and Alexander Downer. It is true, however, that some support exists for Option 2 which is, therefore, more worthy of consideration. There seem to be a few Ministers and Liberal backbenchers supporting Option 2.

Two important points need to be made about Option 2. The first is that, if carried at a referendum held in conjunction with the 2004 general election, it would enable Howard to convene a joint sitting after he had arranged and won a House plus half-Senate election. He would get the best of both worlds – which is the motive behind the whole exercise. The second point is to notice the extent to which it does impair the bicameral nature of the Parliament.

It is true that the present s.57 impairs bicameralism to some degree. The important point, however, is that the present s.57 was drafted in light of the need to get New South Wales to cast an affirmative vote for Federation. To suggest that the present words do not faithfully reflect “the intentions of those who drafted the Constitution” is quite absurd. Every word of it is exactly as they drafted it!

In my opinion s.57 is a splendid piece of wording which has worked remarkably well for over a century. The fact that there has been only one joint sitting is proof of the excellence of the checks and balances of the Constitution. It is bizarre to suggest that the occurrence of only one joint sitting makes the section a failure. What it really means is that New South Wales was persuaded to join the Federation with the minimum impairment of the bicameral system, a veritable triumph for the Founding Fathers. Overall the Constitution strikes the perfect balance between the power of the Prime Minister and the Parliament, between the House of Representatives and the Senate, and between the people and the politicians.

Now that this discussion paper has fallen flat on its face, Howard can make his choice. He can call an election for six Senators per State, or he can call an election for twelve. No doubt Bob Brown strongly hopes he will do the latter. The more The Greens hope for it the less likely it is that Howard will exercise his power to double dissolve. He may want his joint sitting, but he will not want to help Brown and his party to inflict such damage on Coalition numbers in the Senate. Consequently, he will prefer to negotiate the government’s economic reform agenda through the next Senate, when the Coalition’s numbers will be higher than in the present Senate.

Of all the comments in the discussion paper, the one with which I disagree the most is this extraordinary assertion:

“Australia’s experience since Federation is that section 57, as a practical means of resolving deadlocks between the houses, has been all but unworkable”.9

That statement seems to assume that a deadlock must be resolved in favour of the House of Representatives. It is true that only twice (in 1951 and in 1974) has the deadlock been resolved in favour of the House. However, in 1914, 1975, 1983 and 1987 the deadlock was resolved in favour of the Senate. Whereas the paper asserts its “solution” to be “a model which more faithfully reflects the will of the people”, such is exactly what the present arrangements achieve. Among the several reasons why Howard will not double dissolve is that he knows the will of the people is against him on all the disputed legislation.

Essentially it is for that reason I refuse to define a “hostile Senate” as a case where s.57 “triggers” are merely in place. That has been true of the 22nd Parliament (Menzies), the 33rd (Hawke) and the three terms of Howard (see Table 4). Until there is a double dissolution, however, I refuse to accept that the majorities for the two houses are out of harmony. The majorities may be different, in part because of differences in the electoral systems (the more important reason) and in part because so many people split their votes. That cannot be said to produce discord. It merely produces legislation by negotiation.

Table 8: Years House of Representatives and Senate

majorities not in harmony in 20th Century

|

Number of Parliament

|

Years

|

Prime Minister

|

Length of Discord

|

|

5

|

1913–14

|

Cook (Liberal)

|

One year

|

|

6

|

1917

|

Hughes (Nationalist)

|

Two months

|

|

12

|

1930–31

|

Scullin (Labor)

|

Two years

|

|

19

|

1950–51

|

Menzies (Liberal)

|

One year

|

|

28/29

|

1973-75

|

Whitlam (Labor)

|

Three years

|

|

32

|

1982

|

Fraser (Liberal)

|

One year

|

|

34/35

|

1987

|

Hawke (Labor)

|

Ten months

|

|

Century Total

|

|

|

Nine years

|

From time to time the majorities in our two Houses do get out of harmony. In Table 8 is set out my assessment in that regard. It shows just nine years out of 100 in which those majorities were out of harmony; not a great number of years of discord.

In my opinion the proof of the pudding lies in the eating. When four double dissolutions have resolved the dispute in favour of the Senate and only two in favour of the House of Representatives, it is more reasonable to assume “the will of the electorate” (or “the will of the people”) prefers the politicians in the Senate to those in the Lower House. To use the expression “minority interests” to describe the Senate is just propaganda. It is merely polite language for “unrepresentative swill” and is just as wrong. The Government’s discussion paper is nothing more than a dishonest piece of current Liberal Party propaganda. It is very reminiscent of the kind of Labor Party propaganda which was so nauseating during the Whitlam years.

Let me utter a final thought. When I set a recent exam for my students, one question on the paper was this:

“The main purpose of an election is not to reflect ‘the will of the people’, but rather to provide voters with an opportunity to change the government without bloodshed. Do you agree? If so, why? If not, why not?”.

There is no prize for guessing the kind of answer I would give.

Endnotes:

1. Thoughts on the 1949 Reform of the Senate, in Upholding the Australian Constitution, Proceedings of The Samuel Griffith Society, Volume 11 (1999), pp. 251-272.

2. Ibid., p. 252.

3. Source: Ian McAllister, Malcolm Mackerras and Carolyn Brown Boldiston, Australian Political Facts, 2nd edition, Macmillan, 1997, pp. 8, 78 and 80. Updated for the 38th and 39th Parliaments by Malcolm Mackerras.

4. Resolving Deadlocks: A Discussion Paper on Section 57 of the Australian Constitution, Commonwealth of Australia, October, 2003, p. 6.

5. Source: Ian McAllister, Malcolm Mackerras and Carolyn Brown Boldiston, op. cit., pp. 100-106.

6. Resolving Deadlocks, op. cit., p. 47.

7. Ibid., p. 48.

8. Ibid., p. 46.

9. Ibid., p. 26.

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/SGSocUphAUCon/2004/5.html