Melbourne Journal of International Law

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

Melbourne Journal of International Law |

|

TERRITORIAL DISPUTES AND DEEP-SEA MINING IN THE SOUTH CHINA SEA

Territorial Disputes in the South China Sea

ALISON MCCOOK[*] AND DONALD R ROTHWELL[†]

After more than half a century of contemplation and controversy, deep-sea mining is becoming increasingly technologically and economically viable. However, despite its potential, deep-sea mining poses serious environmental and political threats. Understanding the legal regimes that regulate deep-sea mining is crucial for understanding its prospects and consequences and for establishing effective governance.

This article explores the impact of territorial disputes in the South China Sea (‘SCS’) on the regulation of deep-sea mining in the region. It begins by charting the existing territorial disputes in the SCS and the salience of seabed resources to these disputes. It then outlines the legal regimes under which deep-sea mining may be conducted and their comparative benefits. After assessing the impact of the South China Sea Arbitration on these regimes, the article analyses the serious challenges posed to these legal systems by the presence of regional disputes. The interaction between various governing rules, systems and bodies results in an inability to conclusively determine the limits of national sovereignty over the seabed in disputed areas and, consequently, a regulatory lacuna. As a result, this article concludes that legal frameworks for deep-sea mining are hamstrung in the SCS by territorial contests.

CONTENTS

Seabed mining has been mired in legal, political, economic and environmental controversy throughout the past 70 years. It has driven the development of the law of the sea, from the 1945 Policy of the United States with Respect to the Natural Resources of the Subsoil and Sea Bed of the Continental Shelf (‘Truman Proclamation’) to current debates[1] over the International Seabed Authority (‘ISA’) and deep-sea mining under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (‘UNCLOS’).[2] The Truman Proclamation, which asserted the United States’ claim to its contiguous continental shelf, was motivated by US interests in enabling continental shelf mining offshore California and Texas in the Gulf of Mexico.[3] This was a catalyst for the rapid development of state practice, the conclusion of the 1958 Convention on the Continental Shelf (which in turn generated interest in deep-sea mining at the limits of the continental shelf) and the increasing interest of the international community in deep-sea mining beyond the limits of national jurisdiction.[4]

“Deep-sea mining” refers to mining of the continental shelf and deep ocean floor at depths of over 200 metres, as opposed to most seabed mining, which currently occurs in more economically accessible shallow coastal waters.[5] International interest in deep-sea mining at the outer limits of the continental shelf and in the deep seabed began in the 1960s, and the development of the legal regime for “the Area” — the deep seabed beyond national jurisdiction — was central to the third round of negotiations which led to the conclusion of UNCLOS in 1982.[6] During the negotiations, the topic was critical to both the G77 group of developing countries, including China, and to developed nations, particularly the US, which refused to sign UNCLOS due to disagreement over deep-sea mining provisions.[7] Deep-sea mining may occur on the juridical and extended continental shelves (that is, within national jurisdiction) or in the Area.

Although this article’s scope is largely directed at deep-sea mining for solid minerals, it is also relevant to the extraction of hydrocarbons from the deep seabed (in this article, such extraction is referred to as mining).[8] Oil and gas mining provides insight into the politico-legal background for other deep-sea mining. Additionally, hydrocarbon extraction now regularly takes place at depths significantly greater than 200 metres and in areas of extended continental shelf.[9] As outlined further below, the regulatory status of such mining in areas beyond national jurisdiction is unclear (though a full exploration of this issue is beyond the scope of this article), and it is subject to many of the same regulatory challenges as deep-sea mining for critical minerals.

As resource insecurity grows and technological capability develops, resource extraction of hydrocarbons and critical minerals in the deep sea is becoming increasingly viable.[10] In July 2021, Nauru compelled the ISA — the body tasked with regulating mining in the deep sea beyond the continental shelf — to urgently develop and finalise a mining code, and those processes remain under discussion in 2024.[11] In August 2022, the ISA also authorised a trial of deep-sea mining in the Pacific by a Nauru-sponsored company, which commenced in September 2022.[12] In December 2023, the US made a declaration purporting to define the limits of its extended continental shelf in seven offshore areas, a move likely motivated by a desire to secure claims to hydrocarbons and critical minerals in resource-rich seabeds.[13] As the US has not ratified UNCLOS, the declaration was made unilaterally, and stated that continental shelf limits had been determined in accordance with UNCLOS as reflecting customary international law.[14] In January 2024, Norway’s Parliament approved the issue of commercial exploration licences for deep-sea mining on its continental shelf (including its extended continental shelf), becoming the first country to do so.[15] Deep-sea oil rigs are also becoming increasingly prevalent: for example, in April 2022, Canada issued exploration permits for offshore oil and gas exploration approximately 270 nautical miles offshore.[16] Simultaneously, between 2020 and 2022, both hydrocarbon and mineral prices hit record highs, increasing the incentives to expand offshore mining.[17] As a result, after half a century of consideration, commercial-scale deep-sea mining for critical minerals is on the brink of commencing.[18]

These endeavours have the potential to mitigate impending global resource crises, particularly in the energy sector.[19] However, they remain highly controversial due to their serious impact on the marine environment.[20] Leading scientists[21] and environmental groups[22] have emphasised the unknown and possibly irreversible environmental impacts of deep-sea mining in the Area.[23] In 2023, protests from an environmental group against a vessel conducting deep-sea mining exploration activities caused conflict between states, contractors, and the ISA (which defended the contractor by promulgating immediate measures calling on all parties to maintain a safe distance of 500 metres from the vessel).[24] There is now growing momentum for a moratorium on exploitation until further research is conducted, backed by states as diverse as Canada, Chile, Fiji, Palau and the United Kingdom.[25]

The legal governance of deep-sea mining is crucial for both its prospects and consequences, including whether effective regulation of both the industry and its effects on the marine environment can be established.[26] This is especially the case in areas where maritime entitlements and associated boundaries remain unresolved and where tensions exist between coastal states. The South China Sea (‘SCS’) is one such area.[27] As explained further below, these tensions arise because of significant contest between states over their territorial claims to islands, rocks, low-tide elevations, reefs and shoals scattered throughout the SCS. In addition, there are differing views as to the characterisation of these features under UNCLOS and, consequently, their entitlements to maritime zones under the law of the sea.[28] This determines whether these features generate a continental shelf, which ultimately impacts the delineation of the SCS deep seabed and the Area.[29]

This article explores the impact of territorial disputes in the SCS on the legal aspects of deep-sea mining on the continental shelf and in the Area. Given the existing resource and environmental controversies in the SCS, further disagreement between coastal states (and potentially the broader international community) will increase legal and geopolitical tensions in the region. We begin by briefly charting the existing SCS territorial disputes and the growing salience of deep-sea mining in these disputes, before identifying the legal regimes under which deep-sea mining may be conducted. We analyse the intense uncertainty around these regimes in the SCS. In particular, the 2016 award in the South China Sea Arbitration (‘2016 Award’) placed constraints on the ability of coastal states to claim part of the SCS seabed because of its findings regarding the inability of some features to generate a continental shelf.[30]

In this context, the presence of various disputes in the region presents serious challenges to legal and regulatory systems. Several aspects of the current framework interact to create a legal impasse, including the current approach to assessing continental shelf claims in disputed areas, the lack of any clear deadline to make continental shelf claims, and the ambiguous relationship between delineation and delimitation of maritime boundaries. The resulting inability to conclusively determine the limits of national sovereignty over the seabed in disputed areas results in a regulatory vacuum.

As a result of these issues, this article concludes that general legal regimes for deep-sea mining in the SCS are severely constrained by territorial contests. Any form of deep-sea mining will therefore likely occur through unilateral, bilateral or trilateral action outside international law frameworks. These conclusions are also relevant to the prospects and regulation of deep-sea mining in all areas where territoriality or maritime boundaries are contested. By analysing the challenges that conflict poses to current legal regimes for deep-sea mining in contested areas, this article may inform the evolution of more effective regulatory regimes.

Part II of this article outlines the context by describing current territorial claims in the SCS and the impact of seabed resource disputes on these claims. Part III then outlines the legal regimes under which seabed (including deep-sea) mining can be conducted and their implications for the regulation and profitability of such mining. After assessing the impact of the South China Sea Arbitration on these regimes, Part IV analyses the serious challenges posed to regimes by the presence of regional disputes. It concludes that the interaction between various governing rules, systems and bodies results in an inability to conclusively determine the limits of national sovereignty over the seabed in disputed areas and, consequently, a regulatory lacuna. Part V outlines the implications of this lacuna for the future of deep-sea mining in the SCS. This article seeks to reflect law and state practice up to April 2024.

Rights to maritime zones depend on territorial sovereignty over land.[31] In the SCS, the relevant land includes the surrounding continental and archipelagic landmasses, along with islands, rocks, reefs and other features, including the Paracel and Spratly island groups.

Continental Southeast Asia is relatively free of competing territorial claims.[32] Competing claims over North Borneo by the Philippines and Malaysia have recently been raised because of Malaysia’s attempts to claim sovereignty over the adjacent continental shelf.[33] This underscores the importance of seabed resources to territorial disputes, and vice versa. Some island disputes and their status have been settled by the International Court of Justice (‘ICJ’), especially between Indonesia and Malaysia,[34] and Malaysia and Singapore.[35]

In the SCS, competing claims to islands, rocks and reefs drive disputes over maritime areas. While the features themselves are generally small and barren, a coastal state’s ability to control and exploit the resource-rich and strategically critical waters ultimately depends on its ability to establish territorial claims to the features.[36]

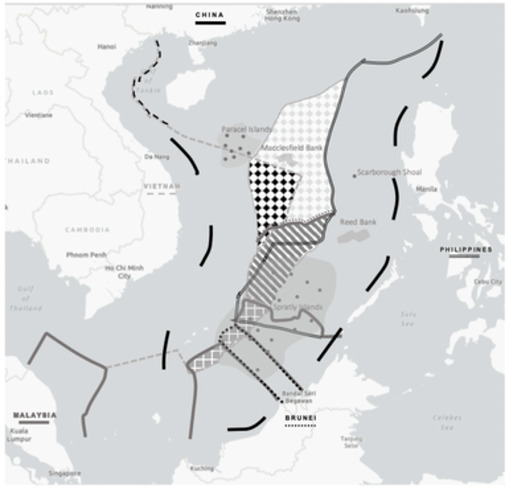

Claims to the waters and features of the SCS are currently made by Brunei, China, Malaysia, the Philippines, Taiwan and Vietnam.[37] While the waters surrounding Indonesia’s Natuna Islands are also disputed, they are beyond the scope of this article.[38] These claims are shown in Figure 1 and are summarised below.

Malaysia’s 2019 CLCS submission

Vietnam 2009 Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (‘CLCS’) submission

Vietnam and Malaysia 2009 CLCS submission (shared development)

Areas beyond continental / archipelagic 200-nautical-mile exclusive economic zone (‘EEZ’) and continental shelf (‘CS’)

Vietnam claim

Malaysia claim

China’s nine-dash line (tenth dash offshore Taiwan not included in map area)

Brunei claim

Philippines claim

Boundary between Vietnam and China delimited by agreement

Figure 1: Claims in the South China Sea, including section beyond the continental or archipelagic 200-nautical-mile extended economic zone and continental shelf.[39]

The Philippines claims sovereignty over the Kalayaan Island Group (‘KIG’) and Scarborough Shoal. While the claim was initially presented as a “box” around the KIG, the current claim appears to be to all claimable features within this box and their appurtenant maritime entitlements as permitted under UNCLOS, acknowledging that none of the features are ‘islands’ under art 121.[40]

Malaysia claims sovereignty over 12 of the Spratly Islands,[41] Brunei claims several features subsumed in its UNCLOS entitlements[42] and Vietnam claims sovereignty over the entire Paracel and Spratly island groups. Vietnam and China have delimited their respective maritime zones in the Gulf of Tonkin.[43]

The nature of China’s (and Taiwan’s) claim is unclear. China has not specified whether its former nine-dash line,[44] and 2023 adjusted ten-dash line,[45] represent a claim to the land features within the line and their ancillary maritime zones, a claim to some non-exclusive, non-territorial historic rights over the entire enclosed area, or, most controversially, a claim to exercise territorial sovereignty over the enclosed waters themselves.[46] Recently, rhetoric has shifted away from the dash lines to the assertion of territorial sovereignty over all features, including low-tide elevations (‘LTEs’), within Nanhai Zhudao (containing, inter alia, the Paracel and Spratly island groups).[47] China also argues that straight or archipelagic baselines can be used in the region.[48] While its use of such baselines is ambiguous, it appears to include drawing straight or archipelagic baselines around the outer boundaries of each group of features, enclosing significant expanses as internal waters.[49]

The above disputes are multifaceted. Taiwan’s status as a legitimate territorial sovereign is not widely recognised, and yet Taiwan occupies territory in the SCS and asserts maritime claims.[50] This is a reality that all SCS coastal states deal with in various ways. Not only is the identity of the territorial sovereign over features contested — a traditional sovereignty dispute — but states also contest whether and to what extent the features are subject to territorial claims.[51] As discussed below, disagreement about features’ status as islands, rocks or LTEs affects whether they can be acquired and the rights that acquisition generates over adjacent waters.[52] For example, the Macclesfield Bank reef is claimed by China; however, it is submerged at high tide and therefore not subject to appropriation.[53]

While a history of these disputes is well beyond this article’s scope, it is worth noting there has been a pattern of confrontation and attempts at pacification since at least the 1970s.[54] The latter include ongoing bilateral negotiations; multilateral negotiations, including the signing of a Declaration on the Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea (‘Declaration’) between the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (‘ASEAN’) and China;[55] the protracted negotiation of a legally binding ‘Code of Conduct’ between the same parties;[56] and the South China Sea Arbitration and 2016 Award.

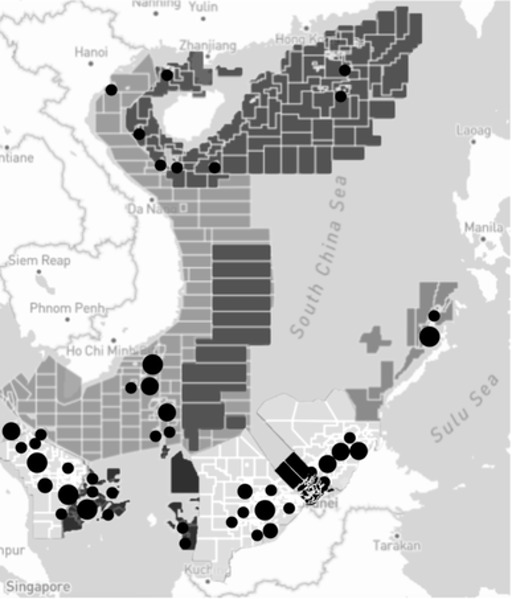

Although the amount of oil and gas resources in the SCS is debated, it is unquestionably significant.[57] Figure 2 depicts oil and gas claim blocks in the SCS as of December 2023, with currently producing oil fields marked with circles. Although this data is incomplete and, in particular, is missing comprehensive information on China’s oil production, it outlines the extent — and overlapping nature — of hydrocarbon claims.

Several key flashpoints in the history of the SCS have been sparked by competition over hydrocarbon resources and drilling. A notable example is the Philippines’ exploration of Reed Bank in the 1970s, which led to tense standoffs with China. While tension over Reed Bank diffused due to less-successful-than-expected drilling results, as the Philippines’ currently producing Palawan oil fields closer offshore are depleted, it may need to turn back to Reed Bank and other oil fields in the SCS.[58] Similarly, there have been clashes between Malaysia and Brunei over drilling in contested border areas.[59] Further, Vietnam and China have a long history of conflict over the presence of oil rigs in their disputed waters, dating from the 1990s and reigniting in 2017 and 2021.[60] This tension is likely to heighten as other regional oil and gas reserves are depleted.[61] However, hydrocarbon exploitation has also operated as an incentive for setting aside territorial disputes in favour of bilateral and multilateral cooperation in the SCS.[62]

Figure 2: Oil and gas claim blocks by country, with currently producing oil fields as at December 2023 marked by black circles.[63]

Future competition may also arise over deep-sea mining for valuable critical minerals, such as copper and nickel, contained within seabed crusts, sulphides and polymetallic nodules.[64] While proposals for mining these minerals were first made in the 1960s, technical challenges and low mineral prices made these early ventures unviable.[65] However, these minerals are required to produce electronics, including batteries, and global demand is projected to soar during the green energy transition.[66] Record prices for these minerals have coincided with technological advances as the commencement of deep-sea mining becomes a realistic prospect. As previously mentioned, the first recent trial of extracting polymetallic nodules from the deep seabed is currently underway in the Pacific.[67] There has also been growing interest in mining phosphorous nodules, as phosphorous-based fertilisers become increasingly important for meeting a growing world’s agricultural needs.[68]

China has longstanding dominance in the global market for these minerals.[69] As domestic and foreign demand grows and China’s land-based mines are depleted, exploitation of the deep seabed will become highly attractive. Seen as the most advanced country in the deep-sea mining “race”, China has invested heavily in deep-sea mining capabilities and has conducted surveys indicating the SCS contains significant polymetallic nodule deposits.[70]

Deep-sea mining projects in the near future are likely to be primarily based in the ISA-regulated Clarion-Clipperton Zone, a remote region of deep seabed in the Pacific, which has long been assessed as a rich source of minerals.[71] Nineteen of the total 31 exploration contracts granted by the ISA relate to this Zone, including two contracts granted to China.[72] However, as technological capability grows, deep-sea mining is likely to expand to other parts of the Area (current areas being explored include the Western Pacific Ocean, Central Indian Ocean and Central Indian Ridge, and Mid-Atlantic Ridge) and to claimed areas of continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles that are contested. Importantly, any mining in the ISA-regulated Clarion-Clipperton Zone (or other parts of the Area) will be subject to mining regulations including the exploration regulations and the emerging exploitation regulations. The developing ISA regulatory regime applicable to mining in the Area, outlined below, may make deep-sea mining in the continental shelf comparatively more profitable. Mining by the coastal state in the continental shelf will not be subject to this regime, which in the ISA-regulated Area may include costly administrative and environmental obligations alongside profit-sharing requirements. This may make SCS deep-sea mining more attractive: ‘the best way for China to ensure continued access to these seabed minerals ... would be to treat [waters holding minerals] as sovereign territory’.[73]

It is important to acknowledge the multifaceted nature of SCS disputes, which are driven not only by seabed resources but also by fisheries conflicts and other political factors.[74] Nonetheless, territorial conflicts are undeniably and inextricably intertwined with seabed mining in the SCS. As shown above, competition over seabed resources has fuelled — and will continue to fuel — territorial conflict in the SCS. Inversely, seabed resources are also used as a tool to reinforce assertions of territorial sovereignty. Surveys, research and resource exploitation may all be used (legitimately or not) as effectivités to legitimise territorial claims.[75]

The international legal regime applicable to exploration and exploitation of the seabed is based upon maritime entitlements within distinctive maritime zones. Recognised UNCLOS maritime zones directly address the sovereignty, sovereign rights and interest of states in the seabed and confer upon them various capacities to engage in seabed mining. Each is discussed below.

Coastal states have sovereignty over a 12-nautical-mile territorial sea, measured from the ‘baselines’ drawn around its coast determined in accordance with UNCLOS, which encompasses the ‘bed and its subsoil’.[76] Territorial sea entitlements are enjoyed offshore the coast of all land, including islands and rocks (subject to delimitation between states with overlapping entitlements).[77] LTEs are not capable of appropriation and do not generate a territorial sea; however, LTEs within an existing territorial sea belong to the coastal state and may be used as a basepoint from which straight baselines are drawn and a territorial sea asserted.[78] Coastal state sovereignty includes the right to freely exploit the territorial sea seabed.[79] Coastal states lacking the capacity to explore and exploit their territorial sea seabed may, consistently with their sovereignty, licence others to do so on their behalf, including foreign entities.[80]

Waters landward of a state’s baselines are internal waters, over which a coastal state enjoys full sovereignty including to the seabed and its resources.[81] The lack of any right of innocent passage for other states constitutes the primary difference in legal rights over the territorial sea and internal waters.[82] Additionally, archipelagic states may draw their baselines between the outermost points of the outermost islands and drying reefs of the archipelago, thus enclosing significant expanses of ocean.[83] The waters enclosed by these baselines are treated as internal waters, though UNCLOS provides for certain rights of passage through archipelagic waters.[84]

Coastal states also have exclusive sovereign rights to explore and exploit the natural resources of their continental shelves.[85] The juridical continental shelf extends a minimum of 200 nautical miles from the baselines, beyond which a complex geographic test may be used to establish an extended continental shelf (‘ECS’) up to a certain limit.[86] A juridical continental shelf is generated by islands, but not by ‘rocks’ under art 121(3) — that is, features incapable of sustaining human habitation or an economic life of their own.[87] As is the case with all maritime zones, a continental shelf is subject to delimitation between states with overlapping entitlements.[88]

While states’ continental shelf entitlements are inherent,[89] fulfilling procedural requirements is vital to create certainty and opposability of ECS limits.[90] To assert an ECS, states must make submissions to the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (‘CLCS’).[91] The CLCS, a body composed of experts in the fields of geology, geophysics and hydrography, assesses these submissions and makes recommendations to the coastal state.[92] Outer limits proclaimed by states based on CLCS recommendations are final and binding.[93] However, as discussed below, the CLCS will not make recommendations in areas where a dispute exists, and so establishing conclusive outer limits may not be possible.[94]

Although it has been said ‘there is in law only a single “continental shelf”’, a distinction nonetheless exists between the juridical continental shelf up to 200 nautical miles and the extended continental shelf beyond.[95] As observed in Delimitation of the Continental Shelf between Nicaragua and Colombia beyond 200 Nautical Miles from the Nicaraguan Coast (‘Nicaragua v Colombia (2023)’), there is a difference in the basis of entitlement to these two continental shelf zones.[96] UNCLOS also establishes a revenue-sharing scheme which applies to the ECS but not the 200-nautical-mile continental shelf.[97] Under art 82, a proportion of mining profits from activities in states’ ECSs must be paid to the ISA, which is to distribute them on the basis of ‘equitable sharing criteria’.[98] While these criteria have not yet been established, the mandatory payment of a proportion of mining profits may adversely affect the profitability of deep-sea mining operations given the significant capital outlay required.[99] The implementation of art 82 is becoming increasingly urgent in light of developments such as Norway’s issue of exploration licences for deep-sea mining for critical minerals in its ECS and Canada’s issue of exploration permits for oil in its ECS, each discussed above. An exemption applies to developing states which are net importers of minerals produced on their continental shelves.[100] Of the SCS coastal states, China would not enjoy that exemption, but other states likely would.

The Area is defined as the ‘seabed and ocean floor and subsoil thereof, beyond the limits of national jurisdiction’.[101] Determining the extent of the Area therefore requires resolution of the limits of the continental shelf.[102] Continental shelf limits for an individual coastal state may variously be determined by a maritime boundary settled with a neighbouring state, by the juridical outer limit of 200 nautical miles recognised by UNCLOS art 76(1), or by the coastal state on the basis of a CLCS recommendation that the coastal state has a juridical continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles as provided by UNCLOS art 76(8).[103]

Part XI of UNCLOS governs activities in the Area.[104] Its scope extends to exploration and exploitation of ‘all solid, liquid or gaseous mineral resources ... including polymetallic nodules’.[105] This definition should, it would seem, include hydrocarbon resources, though interestingly hydrocarbons have seemingly evaded the ISA’s regulatory focus.[106] This is despite the fact that:

Activities with respect to ... the exploitation of ... solid minerals such as polymetallic nodules are still in its [sic] very early stages [whereas] exploration and exploitation for oil and gas in the Area is feasible now [and] oil and gas are the main non-living natural resources.[107]

Hydrocarbon exploration is already underway in regions beyond the 200-nautical-mile continental shelf limit where an ECS has not been conclusively established. For example, in 2017, Mexico and the US agreed on boundaries for oil exploitation in areas of the Gulf of Mexico beyond 200 nautical miles.[108] In issuing calls for tenders for oil exploitation in the region, the US noted that art 82 royalties would apply to activities in the region if the US became a party to UNCLOS.[109] These activities are particularly notable in light of the US’ inability to make a CLCS submission as a non-party to UNCLOS (though, as noted above, it has recently declared the limits of its ECS, which align with the previously agreed boundaries in the Gulf of Mexico). As such, the legal regime over these areas cannot be definitively determined and hydrocarbon extraction will occur in a region where an ECS cannot be conclusively established based on CLCS recommendations. This has implications for the interests of the international community, all of whose members have a legal interest in the Area as part of the common heritage of mankind. The environmental regulation and financial benefit-sharing of hydrocarbon extraction in these indeterminate zones will depend on whether they are ultimately found to be part of a state’s ECS or the Area.

Similarly, Canada is the first UNCLOS party to issue discovery licences in its ECS and is likely to issue the first production license before its ECS boundaries are conclusively established on the basis of CLCS recommendations.[110] However, despite the fact that hydrocarbon exploration is well underway in areas beyond 200 nautical miles (which may or may not be part of the Area) and exploitation may not be too far away, the focus of the ISA has remained on deep-sea mining for solid minerals.

Part XI of UNCLOS was revolutionary in providing that the Area’s resources are part of the common heritage of mankind.[111] As a result, no state can ‘claim or exercise sovereignty or sovereign rights over any part of the Area or its resources’, and all activities in the Area must be consistent with Part XI and the ISA’s rules.[112] In particular, Part XI sets up a benefit-sharing obligation similar to that contained in art 82 in respect of the ECS, requiring ‘equitable sharing of financial and other economic benefits derived from activities in the Area’.[113]

Part XI’s strict language and egalitarian values were mitigated by the 1994 Agreement relating to the Implementation of Part XI of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (‘Agreement on Part XI’), which relevantly lessened payments to the ISA, reduced the ISA’s control over mining approvals and relaxed the requirement that mining profits be equitably shared.[114] The Agreement on Part XI also reduced the role of the Enterprise (the organ of the ISA which was to carry out exploration and exploitation activities in the Area directly) and shifted considerable power from the ISA’s Assembly to the Council (which, unlike the Assembly, is not a plenary organ).[115]

The difficulties of establishing an effective benefit-sharing regime are significant[116] and in 2024 are under consideration during the 29th Session of the ISA.[117] There has been ongoing criticism of the ISA’s proposals, including that they do not reflect the aims of the UNCLOS common heritage regime.[118] Nonetheless, UNCLOS and the Agreement on Part XI undeniably implement a regime which limits the conduct and profitability of deep-sea mining within the Area.

This is particularly salient at present, as the ISA has been compelled to urgently develop and finalise a mining code which will regulate mining in the Area and which in 2024 has been a focal point of discussion at the ISA’s 29th Session.[119] The mining code is the set of rules, regulations and procedures issued by the ISA under the UNCLOS framework to regulate prospecting, exploration and exploitation of marine minerals in the Area, including profit-sharing and other requirements.[120] Exploration regulations have already been developed with respect to polymetallic nodules, polymetallic sulphides and cobalt-rich ferromanganese crusts.[121] Exploitation regulations are under development.[122]

The conduct and profitability of seabed mining by a coastal state therefore depends on its territorial sovereignty and on certainty as to the maritime entitlements that may be generated offshore its coast (including from both adjacent and distant islands). In the SCS, there are multiple factors that contribute to uncertainty as to the extent of a coastal state’s continental shelf and the extent of the Area within which other interested states may be able to operate under an ISA-administered framework consistently with the Part XI regime. Two aspects in particular add to that uncertainty: overlapping maritime claims and the CLCS process to obtain recommendations as to the extent of the juridical continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles.

Asserted continental shelf claims between opposite or adjacent states may overlap in three ways: first, where each coastal state asserts a continental shelf of no more than 200 nautical miles; second, where one state’s 200-nautical-mile entitlement overlaps with another state’s ECS; and third, where states have overlapping ECS claims.

The first type of overlapping claim to the seabed can be resolved through general delimitation dispute resolution mechanisms as outlined in UNCLOS.[123] These extend from negotiation of a maritime boundary to third party dispute settlement, such as resort to the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (‘ITLOS’) or the ICJ.[124] Part XV of UNCLOS provides compulsory procedures for settlement of disputes on the interpretation or application of UNCLOS, though art 298(1)(a) allows states to make declarations refusing to accept such procedures in relation to maritime boundary delimitations.[125] Of the SCS claimant states, only China has made such a declaration.[126] In general, dispute resolution takes place through UNCLOS annex VII arbitration.[127]

Both the second and third types of overlapping claim have been significantly affected by jurisprudence. The possibility of the second type of overlapping claim, albeit rare and to date subject to little state practice, was addressed by the recent decision of the ICJ in Nicaragua v Colombia (2023). The Court determined that ‘under customary international law, a state’s entitlement to a continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles ... may not extend within 200 nautical miles from the baselines of another State’.[128] This view reaffirms that at a minimum, every coastal state enjoys a continental shelf of 200 nautical miles (limited, of course, by any delimitation dispute of the first type). The result is that one coastal state’s juridical entitlement to a continental shelf up to 200 nautical miles will not be diminished by an overlapping entitlement of another coastal state to an extended continental shelf of over 200 nautical miles, even if that ECS is based on CLCS recommendations.[129] While the ICJ in Nicaragua v Colombia (2023) relied upon customary international law because Colombia is not a party to UNCLOS, the decision is equally applicable to the interpretation of the Convention given that it deals with the juridical continental shelf regime.

This judgment has implications for overlapping continental shelf claims in the SCS. Legal continental shelf disputes between opposite states in the SCS — which, because of its geography, are the dominant scenario — will now be reserved to the third scenario: disputes in areas beyond 200 nautical miles from either state’s baselines (the patterned areas in Figure 1).

The resulting centrality of the third type of dispute highlights the significance of the South China Sea Arbitration for the regulation of deep-sea mining in the SCS. The 2016 Award analysed numerous SCS features to determine their UNCLOS status. It found that several claimed features were LTEs and so were not appropriable and did not generate a territorial sea.[130] Further, it applied a relatively restrictive interpretation of art 121(3) of UNCLOS, finding that none of the high-tide features considered by the Tribunal in the Spratly Islands were art 121(3) islands capable of generating a continental shelf.[131] That is, because those features are not juridical islands, they are incapable of generating their own continental shelf and at most only enjoy a territorial sea.[132] Although certain features of the Paracel Islands may be art 121 islands (notably including Woody Island, which has a civilian population at the prefectural-level Sansha City)[133] the 2016 Award’s conclusions regarding the non-island status of features in the Spratly Islands confirm the existence of a “pocket” of deep seabed beyond 200 nautical miles of any coastal states’ territory in the SCS (see Figure 1).[134] This “pocket” of deep seabed is therefore subject to ECS claims and may ultimately be considered to be a part of the Area. Any deep-sea mining taking place would therefore be subject to either UNCLOS art 82 profit-sharing or to ISA regulation of the Area which prohibits mining activity which is not authorised and regulated by the ISA.

The Tribunal also assessed China’s claim to historic rights over the area encompassed within its nine-dash line. It made three particularly relevant findings: first, it implicitly reiterated that rights to maritime zones are contingent on claims to territorial sovereignty, and waters within those zones do not of themselves generate any sovereignty rights;[135] second, it found that there was no evidence China had historic rights in the SCS, and any pre-existing historic rights would regardless be extinguished to the extent they were incompatible with UNCLOS;[136] and third, it confirmed that straight or archipelagic baselines could not be drawn so as to connect the features in question.[137]

With respect to continental shelf entitlements in the areas under consideration, the 2016 Award settles that many features in the area, variously referred to as islands, rocks, reefs or shoals, do not generate a continental shelf.[138] The result is that to legitimately claim resource sovereignty over this sector of the SCS deep seabed, states will be required to conclusively establish ECS entitlements either from the adjoining Southeast Asian mainland coast, archipelagic baselines proclaimed by Indonesia or the Philippines, or from juridical islands.

Given the 2016 Award’s above findings, conclusively determining the extent of SCS ECS claims in order to identify the applicable legal regime for deep-sea mining becomes even more critical. However, in the face of SCS territorial disputes, the capacity of the CLCS to determine ECS claims is compromised.

SCS submissions to the CLCS have been made by Malaysia and Vietnam jointly in 2009,[139] Vietnam in 2009[140] and Malaysia in 2019.[141]

China, the Philippines and Brunei have not made ECS submissions in the SCS, though each has indicated its intention to do so.[142] Taiwan, which is not an UNCLOS party, has also not made a CLCS submission and is not eligible to do so.[143]

These CLCS submissions have been watershed moments in SCS territorial and maritime disputes in several ways. The submissions and the diplomatic responses they have generated are undeniably made tactically to strengthen and to refute sovereignty and maritime claims.[144] They have inflamed pre-existing diplomatic and legal clashes, provoking strong and varied responses.[145] Further, by requiring states to publicly make CLCS submissions regarding their SCS continental shelf entitlements, greater clarity has been given to the extent of certain land and maritime claims.[146]

CLCS submissions encompassing the SCS and the ensuing diplomatic responses emphasise the intractability of regional territorial disputes and the corresponding impossibility of clarifying the legal regime for deep-sea mining. Several aspects of the current legal regime — including, inter alia, the CLCS’s approach to disputed areas, the ambiguous relationship between delineation and delimitation of maritime boundaries beyond 200 nautical miles and the lack of any clear deadline to make ECS submissions — have contributed to legal deadlocks and a regulatory vacuum. This has only contributed to regional geopolitical instability.

Rule 46 of the CLCS Rules of Procedure in conjunction with art 5(a) of annex I provides that where a dispute exists, the CLCS will not consider or qualify submissions made by a party to the dispute unless all parties to the dispute consent.[147] There are two categories of dispute: first, delimitation disputes over the continental shelf between opposite or adjacent states; and, second, other unresolved land or maritime disputes.[148] The broader second category includes, but is not limited to: land disputes regarding sovereignty over features from which an ECS is generated; land disputes regarding sovereignty over features which may generate maritime entitlements overlapping with the claimed ECS; and maritime disputes regarding the entitlements extending from a feature.

As further discussed in the section below, the refusal by the CLCS to consider disputed areas under art 5(a) can create legal and practical deadlocks.

A range of dispute types are present in the SCS, as evidenced by a survey of notes verbales responding to Malaysia’s 2019 submission. The disputes raised explicitly (by invoking art 5(a)) and implicitly in the notes include:[149] (1) delimitation disputes between Malaysia and the Philippines, and between China and other claimant states (‘delimitation disputes’); (2) territorial sovereignty disputes over features in the Paracel and Spratly island groups between Malaysia and the Philippines, between China and the Philippines, and between China and Vietnam; (3) territorial sovereignty disputes over Sabah (North Borneo) between Malaysia and the Philippines; (4) maritime entitlement disputes relating to the ability of features in the Spratly Islands to generate an exclusive economic zone (‘EEZ’) and continental shelf between China and Malaysia, the Philippines, Vietnam, Indonesia and seven other non-claimant states[150] (‘maritime zone entitlement disputes’); (5) maritime entitlement disputes relating to the ability to draw straight or archipelagic baselines around these features between China and the Philippines, Indonesia and seven other non-claimant states[151]; and (6) maritime disputes relating to the ability to claim sovereignty over waters in the SCS based on historic rights between Malaysia and the Philippines, and between China, Malaysia, the Philippines, Vietnam, Indonesia and seven other non-claimant states.[152]

It is unclear from CLCS precedent whether maritime zone entitlement disputes (such as the disputes listed at (4) above) constitute a dispute under rule 46 and art 5(a) of annex I. This is particularly relevant to disputes over whether a feature is a juridical island or a juridical rock, and whether it generates a continental shelf entitlement consistent with art 121 of UNCLOS. Japan’s 2008 CLCS submission, which partly relied on Oki-no-Tori Shima in the North Pacific Ocean as generating a continental shelf, was opposed by China and Korea on the basis that the feature was a rock within the meaning of art 121(3).[153] The CLCS accepted Japan’s argument that its competence did not extend to considering art 121, and therefore, it would not consider whether there was an art 121 dispute. It then established a subcommission to consider Japan’s submission, suggesting these entitlement disputes are not rule 46 disputes.[154]

However, after the subcommission prepared recommendations, the CLCS subsequently stated that ‘it would not be in a position to take action on [the subcommission’s recommendation relating to Oki-no-Tori Shima] until [those] matters ... had been resolved’.[155] It did not refer to the Rules of Procedure, including art 46 or art 5(a) of annex I, in this statement. This makes the legal basis for its restraint unclear, particularly given it has a mandate to provide recommendations and has been criticised for overly curtailing its ability to consider submissions, as discussed below. Regardless, the Commission’s treatment of the claim to Oki-no-Tori Shima indicates that maritime EEZ entitlement disputes will bar final Commission recommendations.[156] Controversially, it also appears to confirm that disputes raised by third-party (ie not opposite or adjacent) states can prevent consideration of submissions.[157] This is particularly relevant to the SCS, where numerous claims overlap and third-party external states (such as Australia, Japan, the UK and the US) have made public objections to claims.[158]

As mentioned above, the CLCS’s refusal to make recommendations in relation to disputed areas is not entirely uncontroversial. The rationale for this refusal is clear, as the CLCS is not a legal body qualified to decide disputes nor should it become a political arena. However, Massimo Lando and Øystein Jensen (among others) have suggested that art 5(a) of annex I to the Rules of Procedure may be ultra vires by contradicting the ‘imperative language’ of UNCLOS art 76(8), which provides ‘[t]he Commission shall make recommendations to coastal States’.[159] Article 5(a) could also be seen as creating a new ‘veto’ right for states, contradicting the explicit intention of UNCLOS parties that the Rules of Procedure should not create new rights.[160]

More generally, the CLCS’s broad approach to identifying disputes has attracted some criticism.[161] Progressive decisions — including allowing maritime entitlement disputes and disputes raised by third-party states to bar resolution of submissions, as discussed above, and deciding that legally binding court and tribunal decisions do not resolve disputes for the purpose of art 5(a), as discussed below — have narrowed the ability of the CLCS to provide final resolution of ECS claims and, consequently, to fulfil the UNCLOS’s goal of providing certainty regarding the scope of maritime entitlements and the Area.[162] As at May 2024, for example, the CLCS had deferred or partially deferred consideration of 26 submissions — one quarter of the 104 total submissions received — because another state had invoked the existence of a dispute under art 5(a).[163] The ramifications of this approach, including creating “deadlock” in disputed areas, are further discussed below.

Regardless of these critiques, because of the disputes numbered above, the CLCS has deferred consideration of the joint 2009 Malaysia and Vietnam submission concerning the South China Sea, the separate 2009 Vietnam submission in the North Area and Malaysia’s 2019 submission in the southern part of the South China Sea. All three submissions have been placed at the back of the queue.[164] The deferral approach stands in contrast to CLCS practice of explicitly choosing ‘not to consider’ submissions in cases of clearly insoluble land disputes (such as the Malvinas and Antarctica).[165] Even allowing for an evolution in the CLCS approach to these matters, and the differences that exist between various territorial disputes and how they are addressed in CLCS submissions, the approach adopted may imply the Commission views the SCS disputes as delimitation-related rather than sovereignty-related and would reconsider the submissions if new developments resolve the disputes.[166] However, the possibility of resolution encounters numerous difficulties.

One of these difficulties is that the exact scope of the disputes and of the boundaries to be delimited is unclear as the Philippines, China and Brunei have not made submissions on their ECS claims in the SCS. Although timely and final resolution of ECS claims was a major purpose of the CLCS regime, the deadline to make full submissions has been extended multiple times. The very existence of any deadline is now highly ambiguous.[167] This ambiguity adds to the ongoing uncertainty and unlikelihood of resolving ECS claims. Without any legal deadline, full submissions by all SCS states do not appear likely in the foreseeable future and the extent of disputes remains unknown.

The clearest path to resolution is that SCS states reach multilateral agreement on territorial claims and the delimitation of their resulting maritime entitlements through purely political means. However, the history and complexity of the disputes make this unlikely.[168]

The legal mechanisms for resolution of territorial and maritime delimitation disputes sit within a framework created under art 33 of the Charter of the United Nations for the peaceful settlement of disputes in which the ICJ, ITLOS and annex VII UNCLOS Arbitral Tribunals all play a role.

The relationship between delineation of continental shelves beyond 200 nautical miles and delimitation of maritime boundaries between opposite or adjacent states is unclear in UNCLOS. The CLCS is at the centre of the delineation of the juridical continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles but plays no direct role in maritime boundary delimitation. This lack of conceptual clarity has been reflected in judicial practice.[169] Delimitation can only occur where there are overlapping entitlements, prima facie requiring states to establish they have a right to an ECS before delimiting it.[170] Accordingly, courts and tribunals initially avoided delimiting maritime boundaries beyond 200 nautical miles in the absence of CLCS recommendations.[171] Such an approach, however, risks deadlock, as the CLCS will refuse to issue recommendations in areas subject to delimitation disputes.[172] Another relevant factor is the significant delays currently experienced in the issue of CLCS recommendations, which is likely to continue for years to come. As of 1 June 2024, the CLCS had 55 submissions queued awaiting consideration.[173]

As a result, beginning with the sui generis Bay of Bengal cases and followed by the preliminary objections decision in Delimitation of the Continental Shelf between Nicaragua and Colombia beyond 200 Nautical Miles from the Nicaraguan Coast (‘Nicaragua v Colombia (2016)’), the ICJ and ITLOS have been prepared to delimit boundaries beyond 200 nautical miles notwithstanding the absence of CLCS recommendations.[174] The admissibility of a request to delimit boundaries in such circumstances is not guaranteed: in particular, the preliminary objections decision in Nicaragua v Colombia (2016) found that submissions to the CLCS in accordance with art 76(8) of UNCLOS, which establish the likely existence of overlapping entitlements beyond 200 nautical miles, are a sufficient prerequisite for delimitation by the Court (without recommendations being required).[175] In contrast, Nicaragua’s preliminary submissions, which did not meet the requirements of art 76(8), were insufficient.[176] This has been criticised as incoherent as there appears to be no legal basis for assuming that full submissions establish the existence of an ECS. To do so overlooks the CLCS’s role in making ECS claims legally opposable under UNCLOS.[177] This argument has particular force in the politically charged arena of the SCS seabed, where claims are made tactically.

In contrast, in Delimitation of the Maritime Boundary between Mauritius and Maldives in the Indian Ocean (‘Mauritius v Maldives’), the ITLOS Special Chamber proceeded to delimitation on the basis of a preliminary submission by Mauritius, stating that it ‘does not consider that there is any rule requiring that a submission be made prior to the institution of delimitation proceedings’.[178] The Chamber considered it could not proceed with delimitation because of the existence of ‘significant uncertainty as to the existence of a continental margin in the area in question’, citing Delimitation of the Maritime Boundary in the Bay of Bengal (‘Bangladesh v Myanmar’).[179]

This approach provides a potential escape from the legal deadlock created by the CLCS’s treatment of disputes. However, such an escape is only available where there is “no significant uncertainty as to the existence of a continental margin in the area in question” (presuming the standard applied in Mauritius v Maldives and Bangladesh v Myanmar is followed). It is unclear whether claims in the SCS would meet this standard. It is also worth noting that thus far, there are limited examples of this approach actually providing an escape route: the Bay of Bengal cases were acknowledged to be sui generis, ‘significant uncertainty’ was found in Mauritius v Maldives, and the final judgment in Nicaragua v Colombia (2023) skirted the issue by making its decision on the basis that ECS claims cannot overlap with 200 nautical mile continental shelves.[180]

The presence of both territorial and maritime entitlement disputes (disputes (2)–(6) above) raises further issues requiring an appreciation of the jurisdiction and competence of courts or tribunals under Part XV of UNCLOS and the broader jurisdiction that can be exercised by the ICJ under the Statute of the International Court of Justice. Although the ICJ has a wide-ranging subject matter jurisdiction and is capable of considering territorial and maritime disputes which require an interpretation and application of UNCLOS,[181] ITLOS and annex VII UNCLOS Arbitral Tribunals are generally unable to determine territorial disputes and consider questions of territoriality, although jurisprudence indicates there is scope for limited consideration of ancillary territorial sovereignty issues.[182] While China in 2006 made an UNCLOS art 298 declaration removing, inter alia, disputes about continental shelf delimitation from ITLOS’s jurisdiction,[183] ITLOS would prima facie be able to consider delimitation disputes between all other claimant states, as well as maritime entitlement disputes between all states including China.[184] However, consideration by ITLOS of the significant territorial disputes in the region would likely be impermissible.[185] While the ICJ is likely capable of considering all conflicts in the area (both territorial and UNCLOS-based), no SCS claimant has accepted the ICJ’s jurisdiction over UNCLOS disputes (nor have all claimants accepted ICJ jurisdiction over relevant territorial disputes).[186] As such, bringing a case in any forum would require consent from all parties to the relevant dispute.[187]

Even if these barriers could be overcome and a legally binding award or judgment was given on maritime delimitation, entitlements and sovereignty, it is unlikely that this would be sufficient to allow CLCS consideration of submissions relating to the SCS. CLCS practice indicates that, at least with respect to delimitation, a binding decision cannot negate a dispute’s existence or act as a substitute for the express consent of all relevant parties.[188] It is unclear but likely that the same approach would be taken to decisions on sovereignty and maritime entitlements.

This approach stands in contrast to the approach of ITLOS in Mauritius v Maldives. In that case, the Special Chamber found that a non-binding advisory opinion of the ICJ in respect of questions of sovereignty had made any continued claim of the United Kingdom to the Chagos Archipelago nothing more than a ‘mere assertion’, which was not sufficient to prove the existence of a dispute.[189] This appears to exemplify a pragmatic approach which gives full force to the ‘prior authoritative determination of the main issues relating to sovereignty claims [by a] judicial body’.[190]

As the CLCS is a scientific, rather than legal, body, it should be unsurprising that it has not taken such a pragmatic approach to identifying the existence of disputes under annex I to the Rules of Procedure. The inability of legally binding decisions to nullify a dispute’s existence for the CLCS’s purposes is highlighted by China’s response to the South China Sea Arbitration and the subsequent diplomatic exchanges over Malaysia’s 2019 CLCS submission. Although the 2016 Award “resolved” the disputes over maritime entitlements, baseline entitlements and sovereignty over waters and reduced the scope of potential boundary delimitation disputes, these exchanges demonstrate its lack of effect in resolving the CLCS deadlock.

Legal resolution of the disputes blocking CLCS consideration of submissions in the SCS faces additional challenges. There are very limited prospects for legal resolution of the maritime boundary delimitation disputes in the SCS. Indeed, some scholars debate whether delimitation can legally occur with a claim which has been found to be legally invalid under UNCLOS.[191] Given this context and the findings of the 2016 Award, any legally effective continental shelf delimitation is unlikely to occur in future between China and the Philippines. Even if such delimitation were to occur by consent, other coastal states impacted by the delimitation may seek to diplomatically or legally contest the maritime boundary. Likewise, the 2016 Award is only binding on China and the Philippines and so has not resolved other non-delimitation disputes between other states, including those between China and other coastal states.[192] Due to the multi-sided nature of SCS disputes, any comprehensive legal resolution will need to be binding on all parties to the relevant dispute.

In summary, the presence of multilateral, multifaceted sovereignty and entitlement disputes in the SCS impedes the regulation of deep-sea mining in the region. Several interacting aspects of the current regime also contribute to the lack of legal clarity regarding activities in disputed areas of the deep seabed. The CLCS’s broad approach to identifying disputes has placed courts and tribunals delimiting maritime boundaries beyond 200 nautical miles on a tenuous legal footing. Judicial delimitation decisions made prior to CLCS recommendations could supplant the CLCS’s role, while the CLCS’s refusal to consider disputed areas even after legal resolution will limit the utility of judicial decisions in creating legal certainty.

This inability of the CLCS to consider ECS submissions in the SCS will prevent deep-sea mining from occurring through the ISA as the region cannot be confidently seen as part of the Area. The ISA is also unable to act as a potential broker for the resolution of issues regarding the outer limits of states’ juridical continental shelves in the SCS and the resulting extent of the Area in the region.

From a regulatory perspective, the existence of zones that could be part of the Area but are subject to unresolved ECS claims paralyses the ISA and other supervisory bodies. With the notable exception of its role in implementing art 82 of UNCLOS (payment of royalties for exploitation of the ECS), the ISA’s role is to ‘organize and control activities in the Area’ including enforcing its mandate to protect the environment in the Area.[193] Given the inherent nature of states’ continental shelf entitlements, zones subject to unresolved ECS claims are not likely to be seen as forming part of the Area. Accordingly, the ISA probably lacks jurisdiction to regulate activities in these undetermined zones. It also has no mandate to participate in or challenge the determination of the outer limits of the ECS (and therefore the Area). As such, it is impotent until all territorial issues are resolved.[194]

ITLOS’s Seabed Disputes Chamber provides a further forum for dispute settlement. The Chamber may hear disputes between state parties, the ISA and contractors undertaking activities in the Area in relation to (inter alia) acts alleged to be in violation of UNCLOS or the ISA rules and regulations and contracts for seabed mining activities.[195] This allows both the ISA and other states (and contractors themselves) to enforce regulation over deep-sea mining. However, the Chamber’s jurisdiction is relevantly limited to ‘disputes with respect to activities in the Area’.[196] As such, the Chamber is likely to lack the power to hear cases in relation to areas of deep seabed that could be part of the Area but are subject to unresolved ECS claims or activities therein.[197] While the Chamber may apply a “substantial uncertainty” standard to whether a zone is part of an ECS or the Area, as described above, it seems probable that substantial uncertainty would attach to the status of any claimed ECS zones in the SCS. As a result, like the ISA, the regulatory power of the Seabed Disputes Chamber is effectively paralysed by the existence of unresolved ECS claims.

The SCS is one of the most deeply contested areas in the world. The geography of the region is highly complex. It involves numerous proximate states with long histories of engagement, making individual and collective territorial claims over hundreds of features, each with varying legal status. The intersection of these issues with UNCLOS maritime entitlements creates exceptional challenges for notions of territoriality that have rarely been encountered since World War Two. These challenges are particularly evident in the juridical continental shelf and the Area because of the deep seabed’s rich resources. This intensifies the territorial, maritime and resource-related challenges over deep-sea mining.

As a result, it is unlikely that deep seabed activities or resolution of territorial challenges in the SCS will be conducted within the mechanisms originally devised by UNCLOS or with any certainty as to the applicability of the relevant international law frameworks. Despite perfunctory attempts to pigeonhole claims within the applicable legal framework, states’ approaches and solutions to the contests have generally occurred outside these regimes.[198] For example, the Declaration between ASEAN and China, a non-binding agreement to promote stability, was seen as a breakthrough in the regional impasse that had developed.[199] However, the Declaration did not prevent the Philippines from commencing proceedings against China over its SCS conduct, and has not placed constraints on China’s construction of artificial islands in the SCS. The hopes for a legally binding code of conduct achieving a resolution of these issues appear slim.[200] This aversion to legal regimes may be a result of the failure of traditional regimes to account for longstanding, politically complex territorial disputes which are not amenable to legal resolution; and the preference of regional states for cooperative, rather than legal, approaches.[201] These aspects mutually reinforce each other.

As outlined above, the CLCS, ISA and UNCLOS Part XV dispute settlement bodies all lack a clearly defined role in resolving these SCS issues. This is due to the complexity of the SCS’s territorial and maritime issues and because UNCLOS was not designed as a legal instrument to resolve and manage territorial issues. Outside of UNCLOS frameworks, other extra-juridical resolution mechanisms may gather support. Joint development agreements can occur within existing legal frameworks (such as provisional arrangements between states with continental shelf delimitation disputes under art 83 of UNCLOS) or outside these frameworks (such as between SCS states with broader territorial disputes).[202] There is a track record of joint development agreements in areas of seabed with hydrocarbon potential,[203] including in the SCS between Malaysia and Brunei, Malaysia and Vietnam, and China and the Philippines.[204] The latter is particularly notable as it was entered into despite the 2016 Award debarring the legitimacy of China’s claims and so may undermine the Philippines’ legal position on its SCS claims.[205] This suggests the Philippines is willing to sacrifice legal rights for political gain, reiterating the impotency of legal frameworks and resolutions for seabed exploitation in the face of territorial conflict in the region.

In addition, without bilateral, regional or multilateral resolution of these issues, unilateral exploitation of the SCS seabed by multiple states is continually taking place.[206] Such unilateral exploitation may be incentivised by recent international judicial treatment of oil and gas activities in disputed seabed areas. In Delimitation of the Maritime Boundary between Ghana and Côte D’Ivoire, the ITLOS Special Chamber found that damaging unilateral drilling activities undertaken by Ghana in disputed areas did not breach the UNCLOS art 83(3) obligation ‘not to jeopardize or hamper’ delimitation agreements and to act without prejudice to final agreed boundaries because it was conducted in areas which were eventually found to belong to Ghana.[207] This implies that unilateral exploitation of disputed areas will not be deemed illegal if those disputed areas are finally found to belong to the exploiting party and, further, that such activities will in any case not be deemed illegal until boundaries are finally delimited. This approach could ‘[motivate states] to undertake as many unilateral oil exploration and exploitation activities as possible’.[208] Similarly, in contrast to the earlier decision in Delimitation of the Maritime Boundary between Guyana and Suriname,[209] the extent, intensity and ongoing nature of Ghana’s oil exploitation — which created a ‘risk of considerable financial loss to Ghana’ if suspension occurred — led the Chamber to find that suspending Ghana’s activities would impose an ‘undue burden’.[210] Again, this jurisprudence could incentivise states to implement more intensive exploitation activities in disputed areas.

It is worth noting, however, that this is not guaranteed. Joanna Dingwall hypothesises that given the ‘significant investment required to mount deep seabed mining operations, it does not seem credible that an actor would engage in mining activities without a clear legal basis and enforceable legal title’.[211] From that perspective, it is possible that the allure of deep-sea mining may in fact drive SCS claimant states to politically cooperate and resolve disputes in order to circumvent paralysis within regulatory bodies and create a secure regime for their investments.[212]

The environmental dimension of these issues should not be ignored. In addition to calls for a mineral mining moratorium being applied to the Area, Virginie C Tilot et al have recently proposed specific management tools such as a sustainability index adapted to deep-sea mining for solid minerals in order to foster sustainability and engagement with affected communities.[213] The implementation of such measures requires clarity on the legal regime under which any deep-sea mining is operating and the bodies responsible for managing it. Although mechanisms such as joint development zones may allow deep-sea mining (including hydrocarbon extraction) to proceed in the face of territorial conflicts, the absence of a secure role for the CLCS, ISA or dispute settlement bodies presents challenges to the effective governance of resource extraction in these areas. For example, imposing the various obligations and protections set up under UNCLOS — such as benefit-sharing and environmental protection requirements — faces serious hurdles.[214] The need for regulation is not limited to these issues — the 2023 Nauru incident referred to above, in which the ISA felt compelled to intervene in a conflict between environmental protestors and a contractor, demonstrates the highly volatile nature of these activities and the need for effective governance.[215]

As shown, the extent and complexity of territorial disputes in the SCS bar any resolution of ECS claims. This means the legal regime applicable to deep-sea mining cannot be established in the short-to-medium term. Not only is it impossible to determine the Area’s limits, but it is practically impossible to legally resolve delimitation disputes between overlapping continental shelf claims and entitlements. The legal regimes and bodies created to govern deep-sea mining are effectively thwarted.

Although the above factors indicate that deep-sea mining in the SCS will likely occur outside the mechanisms originally devised in UNCLOS for these activities, it remains important to understand the legal framework in which these developments are occurring. This is vital to hold states accountable for breaches of international law and to identify and correct deficiencies in that law. As deep-sea mining becomes increasingly viable and profitable, effective regulation will be key to ensuring exploitation occurs in an environmentally and economically sustainable manner.

[*] Associate, Supreme Court of the Australian Capital Territory; LLB (Hons I, Medal), BPPE (ANU).

[†] Professor of International Law, ANU College of Law, ANU, Canberra, Australia.

[1] Policy of the United States with Respect to the Natural Resources of the Subsoil and Sea Bed of the Continental Shelf, 3 CFR 39 (1945) (‘Truman Proclamation’). See, eg, Tullio Scovazzi, ‘The Frontier in the Historical Development of the International Law of the Sea’ in Richard Barnes and Ronán Long (eds), Frontiers in International Environmental Law: Oceans and Climate Challenges (Brill Nijhoff, 2021) 217, 229; Virginie Tassin Campanella, ‘Introduction’ in Virginie Tassin (ed), Routledge Handbook of Seabed Mining and the Law of the Sea (Routledge, 2024) 1, 3–5; Catherine Blanchard et al, ‘The Current Status of Deep-Sea Mining Governance at the International Seabed Authority’ (2023) 147 Marine Policy 105396:1–9, 2; International Seabed Authority, ‘ISA Council Closes Part III of the 28th Session with the Agreement to Deliver the Consolidated Text of the Draft Exploitation Regulations to Pursue Negotiations in March 2024’ (Press Release, 9 November 2023) <https://www.isa.org.jm/news/isa-council-closes-part-iii-of-its-meetings-and-concludes-its-28th-session/>, archived at <https://perma.cc/6KE8-JBQM>.

[2] United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, opened for signature 10 December 1982, 1833 UNTS 396 (entered into force 16 November 1994) (‘UNCLOS’).

[3] Truman Proclamation (n 1), discussed in Ann L Hollick, ‘US Oceans Policy: The Truman Proclamations’ (1976) 17(1) Virginia Journal of International Law 23; Surabhi Ranganathan, ‘Ocean Floor Grab: International Law and the Making of an Extractive Imaginary’ (2019) 30(2) European Journal of International Law 573, 580.

[4] Robin Churchill, Vaughan Lowe and Amy Sander, The Law of the Sea (Manchester University Press, 4th ed, 2022) 221–7; Convention on the Continental Shelf, opened for signature 29 April 1958, 499 UNTS 311 (entered into force 10 June 1964).

[5] Hance D Smith, ‘Introduction to Deep Sea Mining Activities in the Pacific Region’ (2018) 95 Marine Policy 301, 301; Kathryn A Miller et al, ‘An Overview of Seabed Mining Including the Current State of Development, Environmental Impacts, and Knowledge Gaps’ (2018) 4 Frontiers in Marine Science 418:1–24, 2; ‘Deep Seabed Mining’, The Ocean Foundation (Web Page) <https://oceanfdn.org/seabed-mining/>, archived at <https://perma.cc/LJ3Q-HLQU>.

[6] LDM Nelson, ‘The New Deep Sea-Bed Mining Regime’ (1995) 10(2) International Journal of Marine and Coastal Law 189, 189–90; Morella J Calder and Anne M Robinson, ‘Deep Sea Mining and the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea 1982’ [1983] Australian Mining and Petroleum Law Association Yearbook 455, 455, 471–2.

[7] James L Malone, ‘The United States and the Law of the Sea After UNCLOS III’ (1983) 46(2) Law and Contemporary Problems 29.

[8] For the purpose of the analysis that follows, the extraction of any non-living resource from the seabed is “mining”, including continental shelf mining, deep-seabed mining and the extraction of hydrocarbons (oil and gas resources) from the seabed. Although deep-sea mining is commonly used in the literature to refer only to mining for solid minerals, as outlined further below, UNCLOS does not define mining, but does make clear that a range of activities associated with non-living resources on the seabed can occur and that such resources are to be referred to as ‘minerals’: art 1(3) defines ‘activities in the Area’ to encompass ‘all activities of exploration for, and exploitation of, the resources of the Area’; art 133(a) defines ‘resources’ as ‘all solid, liquid or gaseous mineral resources in situ in the Area’; and art 133(b) provides that ‘resources, when recovered from the Area, are to be referred to as “minerals”’. The terms ‘mining’ and ‘extraction’ were used interchangeably by the annex VII Arbitral Tribunal in the South China Sea Arbitration, where it was observed that ‘[s]eabed mining was a glimmer of an idea when the Seabed Committee began the negotiations that led to the Convention. Offshore oil extraction was in its infancy and only recently became possible in deep water areas’: South China Sea Arbitration (Philippines v China) (Jurisdiction and Admissibility) (2015) 170 ILR 1 (‘2015 Jurisdiction and Admissibility’); South China Sea Arbitration (Philippines v China) (Award) (2016) 33 RIAA 153, 290 [270] (‘2016 Award’) (together, the ‘South China Sea Arbitration’). See also the discussion on the interpretation of art 133 and the relationship between resources, minerals and mining in Part XI and UNCLOS generally: Tullio Scovazzi, ‘Article 133: Use of Terms’ in Alexander Proelss (ed), United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea: A Commentary (Verlag CH Beck oHG, 1st ed, 2017) 936, 938–9.

[9] Mark F Randolph et al, ‘Recent Advances in Offshore Geotechnics for Deep Water Oil and Gas Developments’ (2011) 38(7) Ocean Engineering 818, 818–19; James G Speight, Handbook of Offshore Oil and Gas Operations (Elsevier, 2014) 161–2.

[10] Rahul Sharma, ‘Deep-Sea Mining: Current Status and Future Considerations’ in Rahul Sharma (ed), Deep-Sea Mining (Springer, 2017) 3, 12–14; Ralph Watzel, Carsten Rühlemann and Annemiek Vink, ‘Mining Mineral Resources from the Seabed: Opportunities and Challenges’ (2020) 114 Marine Policy 103828:1–2, 1.

[11] Nauru Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, ‘Nauru Requests the International Seabed Authority Council to Adopt Rules and Regulations within Two Years’ (Press Release, May 2021) <http://www.nauru.gov.nr/government/departments/department-of-foreign-affairs-and-trade/faqs-on-2-year-notice.aspx> , archived at <https://perma.cc/7SAG-N8JN>; International Seabed Authority (n 1).

[12] Marian Faa and Jordan Fennell, ‘Pacific Islands Remain Divided on Deep-Sea Mining as Trial Begins to Extract Precious Metals from Ocean Floor’, ABC News (online, 15 September 2022) <https://www.abc.net.au/news/2022-09-15/deepsea-mining-pacific-ocean-nauru-metals/101438478>, archived at <https://perma.cc/2FE6-7D4C>.

[13] Caitlin Keating-Bitonti, Outer Limits of the US Extended Continental Shelf: Background and Issues for Congress (Report, 7 February 2024) 14; Danielle Bochove, ‘US Claims Huge Chunk of Seabed Amid Strategic Push for Resources’, Bloomberg (online, 23 December 2023) <https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-12-22/us-claims-huge-chunk-of-seabed-amid-strategic-push-for-resources>, archived at <https://perma.cc/HPM9-CGBD>; James Kraska, ‘Strategic Implication of the US Extended Continental Shelf’, Wilson Center (Web Page, 19 December 2023) <https://www.wilsoncenter.org/article/strategic-implication-us-extended-continental-shelf>, archived at <https://perma.cc/3UZA-WE34>.

[14] US Department of State, ‘Announcement of US Extended Continental Shelf Outer Limits’ (Media Release, 19 December 2023) <https://www.state.gov/announcement-of-u-s-extended-continental-shelf-outer-limits/>, archived at <https://perma.cc/XE3B-7LR3>; US Department of State, The Outer Limits of the Extended Continental Shelf of the United States of America: Executive Summary (Report, 2023) 6.

[15] Norwegian Ministry of Energy, ‘Norway Gives Green Light for Seabed Minerals’ (Media Release, 10 January 2024) <https://www.regjeringen.no/en/aktuelt/norway-gives-green-light-for-seabed-minerals/id3021433/>, archived at <https://perma.cc/TJ37-7Q7H>; Norwegian Offshore Directorate, ‘Parts of the Norwegian Shelf Can Be Opened for Mineral Activity’ (Media Release, 9 January 2024) <https://www.sodir.no/en/whats-new/news/general-news/2024/norwegian-shelf-opened-for-mineral-activity/>, archived at <https://perma.cc/Y7AG-3P5L>; Ashley Perl, ‘Mining the Depths: Norway’s Deep-sea Exploitation Could Put It in Environmental and Legal Murky Waters’, The Conversation (online, 1 February 2024) <https://theconversation.com/mining-the-depths-norways-deep-sea-exploitation-could-put-it-in-environmental-and-legal-murky-waters-220909>, archived at <https://perma.cc/EA93-7MXE>; Natasha Gilbert, ‘First Approval for Controversial Sea-bed Mining Worries Scientists’ (2024) 625(7995) Nature 435, 435.

[16] Minister of the Environment (Canada), Decision Statement: Issued under Section 54 of the Canadian Environmental Assessment Act 2012 (6 April 2022); Aldo Chircop, ‘Implementation of Article 82 of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea: The Challenge for Canada’ in Catherine Banet (ed), The Law of the Seabed: Access, Uses, and Protection of Seabed Resources (Brill Nijhoff, 2020) 371, 374.

[17] Ron Bousso, ‘Big Oil Doubles Profits in Blockbuster 2022’, Reuters (online, 8 February 2023) <https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/big-oil-doubles-profits-blockbuster-2022-2023-02-08/>, archived at <https://perma.cc/57NV-2DZM>; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission, ‘International Oil Prices Drove Petrol Prices Higher Despite Excise Cut’ (Media Release, 5 September 2022) <https://www.accc.gov.au/media-release/international-oil-prices-drove-petrol-prices-higher-despite-excise-cut>, archived at <https://perma.cc/TZ8N-SKT8>.

[18] Joanna Dingwall, ‘Commercial Mining Activities in the Deep Seabed beyond National Jurisdiction: the International Legal Framework’ in Catherine Banet (ed), The Law of the Seabed: Access, Uses, and Protection of Seabed Resources (Brill Nijhoff, 2020) 139, 156–61.

[19] Raphael Deberdt and PL Billon, ‘Green Transition Mineral Supply Risks: Comparing Artisanal and Deep-Sea Cobalt Mining in a Time of Climate Crisis’ (2023) 14 Extractive Industries and Society 101232:1–10, 6; Norman Toro, Pedro Robles and Ricardo I Jeldres, ‘Seabed Mineral Resources, An Alternative for the Future of Renewable Energy: A Critical Review’ (2020) 126 Ore Geology Reviews 103699:1–12, 1.

[20] See, eg, Sylvia Earle and Daniel Kammen, ‘The Case against Deep-Sea Mining’, Time (online, 25 October 2022) <https://time.com/6224508/deep-sea-mining-threat-ban/>, archived at <https://perma.cc/B897-J8NR>.

[21] European Academics Science Advisory Council, ‘Deep-Sea Mining: Assessing Evidence on Future Needs and Environmental Impacts’ (Report, June 2023); Diva J Amon et al, ‘Heading to the Deep End without Knowing How to Swim: Do We Need Deep-Seabed Mining?’ (2022) 5(3) One Earth 220.

[22] Greenpeace International, ‘The Oceans Need a Deep Sea Mining Moratorium, Not Regulations that Allow Destruction’ (Press Release, 8 November 2023) <https://www.greenpeace.org/international/press-release/63549/the-oceans-need-a-deep-sea-mining-moratorium-not-regulations-that-allow-destruction/>, archived at <https://perma.cc/4T6N-SMRU>.

[23] Olive Heffernan, ‘Seabed Mining is Coming: Bringing Mineral Riches and Fears of Epic Extinctions’ (2019) 571(7766) Nature 465.