Legal Education Review

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

Legal Education Review |

|

Where to Now? The 2002 Australasian Research Skills Training Survey

Terry Hutchinson *

Legal research is a fundamental “lawyering” skill, and as such its importance in legal education has had more recognition than other discipline-specific attributes.1 However, in 1988, when an initial review of research skills training in Australasian law schools was completed,2 the predominant philosophy appeared to be that the skill would be developed via a process of “osmosis”.3 Since then, a transformation of sorts has occurred. Legal research training has become an integral part of the curriculum of most law courses offered within the Australian region. At the same time, skills generally have gained increasing importance in the tertiary sector and especially in the law school curriculum. Within this context, some law schools have instigated reviews of their overall skills training, and this has had a flow-on effect on legal research training. This current Australian legal tertiary framework of enhanced importance for skills training and an increased use of technology for teaching, forms the backdrop for the 2002 survey.

This paper firstly reviews the developments taking place within higher education as reflected in the various government reports. It then outlines the relevant literature on literacy competency within information sciences. Also pertinent is the law schools’ response to doctrinal research skills training. Previous surveys of legal research teaching in Australia are summarised. The paper then examines the outcomes of the 2002 survey and makes some conclusions and recommendations based on the analysis of results taking into account the challenges identified for the tertiary education sector in Australia.

Several reviews of the Australian higher education sector have taken place and these reports have reinforced the need for universities to reconsider the generic skills and personal attributes of the graduates they produce. They also provide a helpful context for understanding the importance of research skills training in legal education. An early review of generic skills was carried out by the Mayer Committee established by the Australian Education Council and Ministers of Vocational Education, Employment and Training.4 The Mayer Report in 1992 set out seven basic generic competencies including the following three:

• Collecting, analysing and organising information. The capacity to locate, sift and sort information in order to select what is required and present it in a useful way, evaluate both the information itself and the sources and methods used to obtain it. • Communicating ideas and information. The capacity to communicate effectively with others using the range of spoken, written, graphic and other non-verbal means of expression. • Using technology. The capacity to apply technology, combining the physical and sensory skills needed to operate equipment with the understanding of scientific and technological principles needed to explore and adapt systems.5

Following this, the West Review produced a useful framework for Australian graduate outcomes, by stipulating that, ideally, every graduate with a first degree should have acquired the following attributes:

• the capacity for critical, conceptual and reflective thinking in all aspects of intellectual and practical activity; • technical competence and an understanding of the broad conceptual and theoretical elements of his or her fields of specialisation; • intellectual openness and curiosity, and an appreciation of the interconnectedness and areas of uncertainty in current human knowledge; • effective communication skills in all domains (reading, writing, speaking and listening); • research, discovery and information retrieval skills, and a general capacity to use information; • multifaceted problem solving skills and the capacity for team work; and • high ethical standards in personal and professional life, underpinned by a capacity for self-directed activity.6

In 1999, the Commonwealth green paper, New Knowledge, New Opportunities7 and the later white paper, Knowledge and Innovation8 looked at research and research training at a broad level within universities. The green paper stated that postgraduate research training “represents one of the most significant areas of national investment in research”.9 The policies being put forward sought to move funding for research and research training to a performance-based system where funding is based on outcomes and the quality of the research being produced in the university. The objective of this strategy was to produce graduates who are more attractive to employers outside the universities and research institutes.10 Again in 2000, the then Minister for Education, Training and Youth Affairs, Dr David Kemp, emphasised the strategic importance of the “encouragement of universities to ensure that their graduates enter the workforce with the competencies needed, including information literacy skills and lifelong learning skills”.11 In addition, the Commonwealth Government was considering ways of testing the development of generic capabilities or attributes using the Graduate Skills Assessment across all universities. This was Commissioned by the then Department of Education, Training and Youth Affairs and introduced in 1999.12 There was some recognition that the current environment, especially involving developments in technology, can lead to dynamic change and therefore there is a need for graduates to have the skills to stay abreast of knowledge shifts in their fields.

For a comparative viewpoint, the 2001 National Centre for Vocational Education Research’s Generic Skills for the New Economy noted the way sets of key competencies/key skills have been developed in Britain, the United States and Australia.13 The NCVER Review of Australian and international literature and research on generic skills noted the changes that had taken place since the Mayer report and especially the effects of globalisation, competitive economies and the technological revolution. It found this had changed the needs of employers and requirements for workers’ competencies. It also noted that the shift to active learning techniques is needed to develop generic skills throughout a working life.14

The 2002 Review of Higher Education, initiated by the Minister for Education, Science and Technology, Dr Brendan Nelson,15 has prompted further debate concerning all aspects of university education in Australia. Relevant to our discussion is the following statement regarding the purpose of tertiary education:

Higher education fulfils significant functions in our society. It values learning throughout life. It promotes the pursuit, preservation and transmission of knowledge. It extols the value of research, both “curiosity-driven” and “use-inspired”. It enables personal intellectual autonomy and development. It provides skills formation and educational qualifications to prepare individuals for the workforce. It helps position Australia internationally.16

Therefore, once again, the themes of lifelong learning and autonomous learning, along with the importance of research and skills are being emphasised at higher government policy levels.

Within the tertiary library community, heightened awareness has centred on the issue of information literacy. The United States Association of College and Research Libraries17 defined information literacy as a set of abilities requiring individuals to “recognize when information is needed and have the ability to locate, evaluate, and use effectively the needed information”.18 This report identified five standards as being:

1 The information literate student determines the nature and extent of the information needed. 2 The information literate student accesses needed information effectively and efficiently. 3 The information literate student evaluates information and its sources critically and incorporates selected information into his or her knowledge base and value system. 4 The information literate student, individually or as a member of a group, uses information effectively to accomplish a specific purpose. 5. The information literate student understands many of the economic, legal, and social issues surrounding the use of information and accesses and uses information ethically and legally.

These standards were published post-Boyer,19 and were certainly influenced by the ideas espoused in that report, particularly the “Ten Ways to Change Undergraduate Education”:

• make research-based learning the standard • construct an inquiry-based freshman year • build on the freshman foundation • remove barriers to interdisciplinary education • link communication skills and course work • use information technology creatively • culminate with a capstone experience • educate graduate students as apprentice teachers • change faculty reward systems • cultivate a sense of community.

The Council of Australian University Librarians (CAUL) published a list of core standards based largely on the US list in 2001. A revised Australian list was published in 2003 after an exhaustive consultation process. The new Standard Four includes an ability to “record information and its sources” and to organise this information.20 It states: “The information literate person manages information collected or generated.” Standard Five states that the information literate person “applies prior and new information to construct concepts or create new understandings”.21

Information literacy has been considered to provide a pedagogical or theoretical teaching framework for legal research practice.22 Christine Bruce’s theory on information literacy places reader education or research training development in an historical framework and so demonstrates an interesting parallel to the developments in legal research skills training. She notes that the “bibliographic” movement was the prominent focus in libraries in the 1980s.23 This was so in legal research training circles as well, until it was replaced by the Wrens’ push towards teaching legal research as a process.24 More recently, interdisciplinary research incorporating empirical methodologies and additional theoretical, policy and reform aspects have been included in the curricula.25 These connections between information literacy and the theory behind research skills teaching are very important to the overall development of reflective practice and scholarship in this area. Fitzgerald identified the lack of “theory-based research on skills” in 1996 as being one of the main reasons why skills had been slow to enter the law school curriculum.26

Legal research is a traditional legal skill. However, the various reports on legal education documented the slow rate of change in relation to skills training. Beginning with the 1987 Pearce report,27 and the subsequent McInnis and Margison report in 1994,28 there was recognition that “any movement towards skills development within law schools had been slow”.29 In the United States, the 1992 McCrate Report on legal education had identified a list of fundamental lawyering skills. Of course, legal research figured in that list.30 Given these developments, it is not surprising that the Australian Law Reform Commission, in its 1999 report on managing justice, called for legal education to focus on “what lawyers need to be able to do” rather than “what lawyers need to know”.31 By 2003, Johnstone and Vignaendras’ “stocktake” of legal education in Australia reported that “arguably the most significant of all of the developments in Australian legal education in the past decade is the focus on teaching legal skills within the undergraduate curriculum”.32

One school, for example, has developed a framework to develop “graduate attributes”.33 The school identified the six attributes of a law graduate. A graduate who possesses the nominated attributes will generally be able to demonstrate a variety of skills.34 There are 26 skills, which have been broadly categorised as attitudinal (including reflective practice), cognitive (including legal research and IT literacy), communicative (including oral and written communication), and relational skills (time/project management). The skills have been integrated with the content of the compulsory units within the undergraduate LLB and incrementally developed up through the degree in three broad levels of skill progression, which move from generic to more legally specific and ultimately more complex applications. Thus, legal research has been integrated into the law degree through three levels over the four years of the degree.35 There is also an advanced level available through the Research Project unit elective, which is offered to later year students who may want to research and write on a specific topic under academic supervision. This is merely an example of one school’s approach to integrating skills in the curriculum.

In order to chart the development and challenges of teaching legal research skills, it is useful to be reminded about the results of previous surveys. An initial scan and informal survey in 1988 demonstrated that very few law schools were “attempting to teach legal research in a formal manner”.36 By 1991, the scene was changing. Thirteen of the universities surveyed had introduced research training since 1988, three in 1990 and six in 1991. Perceived weaknesses in the courses resulted from inadequate staffing, inadequate facilities and the corresponding lack of motivation seen in the students.37

The 1995 survey covered 30 Australian, New Zealand and Papua New Guinea Law schools in June 1995. The survey generally covered the issues of orientation courses for first year students, the provision of undergraduate and postgraduate research courses, and the inclusion of legal writing in the curriculum. Some emphasis was placed on the issue of computer-assisted research and the inclusion of this in the courses. Respondents were asked whether social science and empirical research methods were included in the units. Respondents were also asked to rank some of the main difficulties encountered in the courses.

Nineteen responses were received as was reported at the inaugural meeting of the Legal Research Communications Group at the Australasian Law Teachers Association (ALTA) Conference at Flinders in 1995.38 At that stage, the survey demonstrated that most law schools were offering some form of legal research training, mainly at undergraduate level. However, some were also conducting orientation courses for first year, and about half had some training schedule for postgraduates.

The majority of the schools therefore were offering first year courses and three were offering an integrated skills program. At that point, seven reported a compulsory separate subject dealing with research in first year. Another eight reported research being taught as a segment of a compulsory first year subject, which was a very positive development, although in most of these units, the research training segment was limited to 20 hours or less of a full year unit.

Most of the research units included some writing instruction. This basically consisted of assignment writing, with less emphasis being given to a broader range of pertinent writing genres such as barrister’s opinions, briefs to counsel, case notes, letters to clients, internal office research memorandums and journal articles.

The main method of assessment was, not surprisingly, through assignments and seminar performance. However, it was disappointing to note that a few were still using the standard law school examinations, even though this is certainly not the most effective way to assess research. Perhaps this was indicative of staffing levels available for the units because less staff time is normally required to mark one exam than to mark a longer research assignment.

Although the teaching teams consisted principally of academics, there were many instances reported of combined academic and librarian teaching teams. However, overall the teaching teams seemed to be very small, which suggested very high staff/student ratios. When asked about the problems being encountered with the units, it is not surprising that this response was most prevalent, the others being resource problems and motivating students. So the difficulties that had been raised in the 1991 survey were highlighted once more, and these seem not to have disappeared, judging by the most recent survey responses.

The 2002 survey instrument was based on the previous surveys in order to allow for some comparison. Survey forms were sent to the Deans of all law schools for distribution to their legal research teaching staff. Forms were also sent to the law librarians at all law schools in Australia (30) and those in New Zealand (5). In addition, the survey was distributed through the ALTARESCOM email discussion list. This list consists of those within the Australasian Law Teachers Association Legal Research and Communications Interest Group, and includes many of the legal research teachers in Australian law schools.39 Other teachers were identified from the web unit outlines and surveys were sent directly to their email addresses.

This resulted in 31 surveys being returned, with respondents from all six States and the Australian Capital Territory. There were more responses received from New South Wales and Queensland than other jurisdictions. The respondents included all academic levels from Professor to Associate Lecturer as well as law librarians. In all, 25 institutions were represented.

In the modern context, most law schools have a web presence. A detailed examination of these websites was undertaken as part of this project. Research unit details that were available were analysed and some comments are directed to the information provided there.

The 2002 survey responses were anonymous, in conformity with university ethics requirements. As a result, confidentiality was assured. However, it was also the case that more than one response was received from some law schools, with individual respondents simply addressing the specific units they were involved in teaching. The figures in the following analysis indicate numbers of institutional responses and where all individual respondents are included, this is clearly indicated.

These survey questions also assumed that electronic research methods would be covered in some detail given the changed context in the last seven years brought about by the widespread use of the Internet. In the interests of brevity, there was less emphasis on asking for detailed information about the curriculum, given the increasing number of research texts published for this market. Teaching methods were not surveyed. At the time of the earlier surveys, some schools were still trying to teach research using a lecture format, but it was thought that such crude ways of teaching skills would no longer prevail in the current climate.40

Thus, although the survey asked how many students were enrolled overall in the units for each year, the question was not asked how these students were taught. Was the material delivered in small groups, and if so what was the usual size of these groups? Was the material delivered with a mixture of lectures and workshops? How long were the workshops? These questions were not asked but consideration will be given to including them in the next survey.

The initial question was directed at actual research training for the bulk of the student body. The survey asked whether the law school offered subjects teaching research skills at the undergraduate level. There was one negative response to this question.

A scan of the websites for the universities also revealed that nearly all the faculties include the advanced elective, research project unit in their degrees. The research projects are often only encouraged where the students are in the final semesters of their degree and have proven themselves to be high achievers and competent to produce a publishable quality paper on a topic of their own choosing with minimal guidance from an academic expert in their chosen topic area. This is traditionally an opportunity offered to brighter students who may be considering further study and an academic career. These supervised research projects tend not to include any formal research training as envisaged by the terms of this survey question. It is very unlikely that there was any misunderstanding of the question so that respondents covered this unit in their reply.

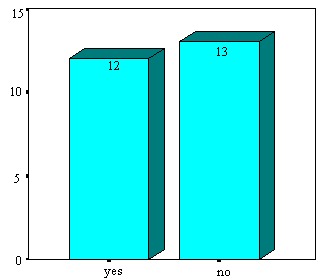

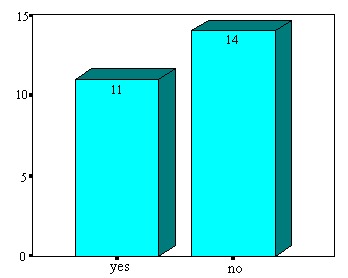

Respondents were asked whether their law faculty offered a traditional Orientation program and tour for first year students in which legal research skills were included. The responses were fairly evenly divided on this.

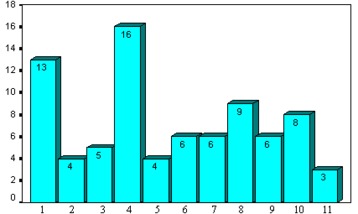

Figure 1

Does the Law Faculty offer an Orientation Course to first year students in which legal research skills are taught?

(n = 25)

If formal courses have been introduced then the schools who are in that category may judge that it is not necessary to pour resources into the traditional introduction and tour of the Law Library, the lecture on “how to write a case note” and the short guide to citation and how to find cases and legislation. This is debatable. One side of the debate would say that students are overwhelmed if they are force-fed information about legal sources in the first week of their degree and it tends to “go over their heads” anyway. There is considerable support for the theory that skills in particular are mastered best at the point of need. Some would argue that this is the reason why hands-on incremental skills’ teaching was introduced in the first place. Perhaps, for these schools, this orientation aspect is now being left to the law library’s organisation of voluntary tours during Orientation Week. The counter argument is that a scaled-down bare-bones introduction is necessary in any case in order to help the students through the first weeks – at least until they begin formal instruction in the intricacies of using legal resources within their research units.

The next series of questions tried to “tease out” some basic aspects of the undergraduate courses being offered. There are several methods of introducing research skills training into the curriculum. The schools seem to fall into categories based on four main issues:

a) whether the research units are compulsory; b) whether the units are separate, or research training is included as part of a larger compulsory foundation unit; c) whether the research skills training is only included in an elective unit; and d) whether there is anything offered beyond first year leading to “capstone” experiences prior to graduation.

A recent government paper on higher education has noted the importance of “capstone subjects” which build on skills acquired in earlier courses and emphasise situations and challenges that exist in the “real world”.41 The study points to the need to “cap” the student’s learning experiences to ensure that the necessary skills and knowledge have been acquired and can be demonstrated.42 The importance of reinforcement of research skills training is receiving some support, judging by the responses on the unit organisation questions.

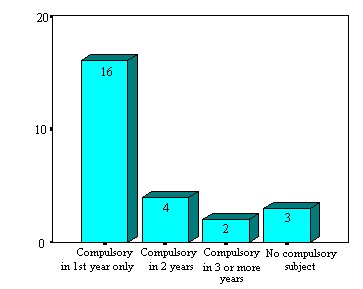

Dealing first with the compulsory nature of the units, it was evident that most law schools had compulsory courses in the first year only. Figure 2 demonstrates that four of the 25 schools reported a compulsory unit being offered at least twice in the degree. Two schools were providing compulsory training in three or more years. Another three responses included those schools where there was no compulsory research subject offering formal training or where research training was only offered as an elective unit.

Figure 2

To what extent is the legal research unit compulsory?43

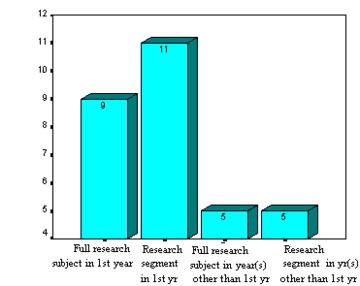

How is the research segment integrated into the curriculum? Is the introductory research training offered as a separate unit or is it merely a segment of another larger foundation unit? Is there a difference between the approach in first year and later years? From Figure 3, it is evident that five responses noted that there were separate research units in later years and the others said these were segments of other year units. It is evident that the main research training is taking place in first year with nine stating there is a discrete research unit in first year and another 11 stating that research is merely a segment of a first year introductory course. This compares favourably to the 1995 result with a slight increase from the seven reporting a separate subject and eight reporting research taught as a segment of a compulsory first year subject. This demonstrates an overall improvement in the take-up between 1995 where there were 15 universities reporting a first year research unit compared to 20 in 2002.

Figure 3

When is the legal research unit offered?44

Another question sought to discover whether the unit was taught over one or two semesters. This issue was more important prior to the overall move to semesterise all units in most law schools, largely because of the introduction of summer semester teaching. Full year units are not prevalent in most law courses now, and not surprisingly all respondents reported one-semester courses.

Questions were directed to determining the relative importance of the legal research training segment based on the number of hours of instruction on research as against other content in the unit. This was especially revealing where legal research was simply a segment of a substantive course. The questions posed were “How many teaching hours are there in the subject?” and “How many teaching hours are dedicated to teaching research in the subject?” Questions were also directed to the number of hours for legal writing instruction and non-doctrinal methodologies instruction in the units. The following tables represent the responses where the legal research unit was compulsory. Some of the results, especially those in Table 1 stating that very few hours are spent on research within the compulsory units, appear contradictory, which seems to suggest that they were misclassified by the respondents.

Table 1

Time spent on research training in compulsory units45

|

Training Time

|

Frequency

|

|

Less than 10 hours

|

4

|

|

11 – 15 hours

|

3

|

|

16 – 20 hours

|

2

|

|

More than 20 hours

|

6

|

|

Total

|

15

|

Table 2

Time spent on writing training in

compulsory research units46

|

Training Time

|

Frequency

|

|

Less than 5 hours

|

8

|

|

6 – 10 hours

|

2

|

|

More than 20 hours

|

2

|

|

Total

|

12

|

It would seem from these responses that writing skills are being included in the research skills units but writing is a relatively minor aspect within the whole. It tends to be relegated to five or less teaching hours. Only in a couple of instances was there an even division of research and writing in the content, despite these courses often being referred to as “research and writing” units.

Where research training is only a part of a larger unit the figures demonstrate, not surprisingly, that fewer hours are allocated to the research segment. The total hours devoted to legal research skills training are very much reduced where research is taught within other units, with six responses noting less than five hours and another six reporting under ten. None had more than 15 hours. From this it is possible to conclude that this aspect of the curriculum will be under pressure with arguably insufficient time being allocated because of the need to fit in other curriculum material. This means that students in some schools are receiving more than 20 hours training in research while students in other schools are receiving less than five hours. There can thus be quite a disparity in emphasis and likely skills development and outcomes for the students at different universities.

Table 3

Time spent on research training where a segment of a compulsory unit47

|

Training Time

|

Frequency

|

|

Less than 5 hours

|

6

|

|

6 – 10 hours

|

6

|

|

11 – 15 hours

|

4

|

|

Total

|

16

|

Table 4

Time spent on writing training where a segment of a compulsory unit48

|

Training Time

|

Frequency

|

|

None

|

12

|

|

Less than 5 hours

|

6

|

|

Total

|

18

|

Where research is a segment of another unit, then understandably the hours listed for teaching writing are also less. There were 18 responses to this question and the majority reported that legal writing was allocated no time. If there was legal writing training it was absolutely minimal, being less than five hours. Where the unit was a compulsory separate subject then all reported having a little writing training – but once again, the majority reported less than five hours.

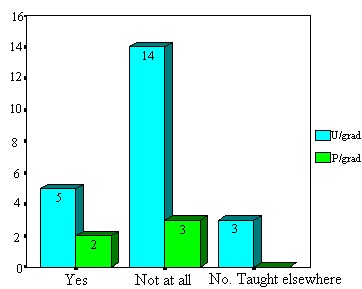

Respondents were asked whether social science or empirical methodologies were covered in the research units. Fourteen respondents replied that there was no social science methods segment in the undergraduate subjects. Only five said that it was taught in the undergraduate degree units. Three respondents stated that there were separate elective units covering these issues. One respondent said such issues were preliminary aspects dealt with for students undertaking an undergraduate research project or essay unit. Only two of the postgraduate units had this training included.

Figure 4

Is there a social science methods segment in the subject?49

Interdisciplinary methodologies are increasingly important in the current general tertiary framework and it would seem that this is an area that will eventually receive some recognition in the research courses. It is not apparently a common curricula inclusion judging from this survey result. Determining just how to deal with the issue of training law students in these methodologies is more troublesome. This is not an aspect that can be covered in even five hours! Perhaps the best method for approaching the teaching of empirical methodologies within the undergraduate law degree is to provide sufficient exposure to the relevant issues in the compulsory units so that the importance of understanding research using non-doctrinal research methodologies is highlighted. A follow-up elective might also be tailored to legal practitioners’ needs.

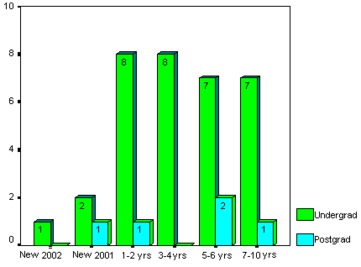

Only 11 of the respondents reported that postgraduate research training courses were being offered for this cohort. The remaining 14 said that there were no such courses. Nine universities were offering postgraduate courses according to the 1995 survey so the situation has only improved slightly. This response is particularly disappointing given the emphasis being placed by government policy on research training needs and completions.

Figure 5

Does the Law Faculty offer subjects teaching legal research at a postgraduate level?

Some respondents commented that postgraduate units were designated compulsory for some students. Other responses indicated that the courses were electives or simply informal instruction. Research training is essential for those postgraduate students who completed their undergraduate degree some years earlier; for international students unused to common law research; for non-law graduates; and for students undertaking large research projects for the first time, such as Masters by research, PhDs and professional doctorates. The units are excellent updates for the bulk of postgraduates, but they should be compulsory for the groups mentioned because some of these students will not have the basic research training provided at undergraduate levels. In addition, those undertaking larger research projects have different needs from undergraduates, in particular, writing research proposals, refining hypotheses and research management training.

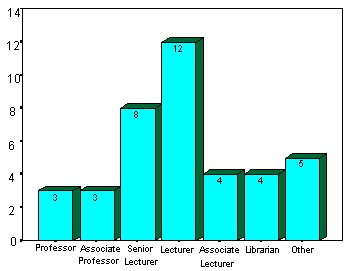

As is evident from the figure below, staff from all academic levels, including Professors and Associate Professors, coordinate the research courses. These units therefore are certainly not universally perceived as of a status to be relegated to lower level or part-time academic staff.

Five units were reported as being jointly coordinated by academics and law librarians. This constitutes the “other” column in Figure 6. This factor might be interpreted in two ways. On the one hand, it might point to the faculties’ commitment to ensuring that the students have the best of both sources of instruction, that is, more technical expertise from the law library staff together with more end-user substantive critique from the academics. It also ensures that the units are viewed as being of similar status to the substantive units. On the other hand, less positive interpretations might be placed on the arrangements, such as:

• academics seeking assistance so as to reduce the inordinately heavy preparation loads involved in the units; • academics seeking assistance because of the logistics of teaching skills to large numbers of first year students; • academics seeking ways to lighten the teaching load in such units because they are not substantive subjects and therefore less likely to lead to productive personal research and publications.

Figure 6

Who is co-ordinating the legal research subject?50

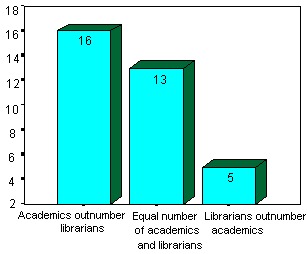

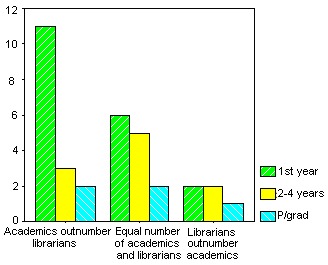

Academic staff outnumber librarians in the teaching of the first year students. This is perhaps because of some very large first year intakes, together with the likelihood that most classes take place in seminar groups of up to 20 students. Some first year intakes are as high as 750 and many later year units number over 300. This results in a great number of seminar classes, which need to be offered each week and also teaching staff who need to be involved. Several of the web outlines were noting that the teaching hours were divided into a one-hour lecture and a one-hour seminar. A variation on this is the 1.5 hour lecture and 1.5 hour seminar each week. These adjustments acknowledge the special aspect of skills teaching and the need for interactive workshops where students are encouraged in active learning or learning by doing. If it is not efficient to learn to ride a bike sitting in a lecture theatre, it is not a useful enterprise to lecture students on how to research. They must actively learn the skill and this normally takes longer than a one-hour seminar timeframe. It is unlikely that law library staff could cope with this type of teaching load. Law libraries can utilise their resources more efficiently by providing technical expertise and training for academics taking first year classes and concentrating on allocating more teaching time to later year units if required.

Figure 7

The number of academics compared to the number of librarians in the teaching team for all the legal research subjects 51

(Covers all year levels)

The teaching team figures tend to be different in the later years when it may be that the academics and law librarians are more likely to take a team approach wherever possible.

Figure 8

The number of academics compared to the number of librarians in the teaching teams for all the legal research subjects

(Breakdown of year levels)

It is gratifying to note the links being forged between law librarians and academic staff through team teaching because this provides the students with both substantive and technical expertise. A computer laboratory skills group requires two trainers to cope efficiently with the individual variation in abilities within a group of 20 students. A librarian/academic team approach should present the students with excellent outcomes in terms of technical knowledge and application to the subject area.

Table 5 demonstrates the array of assessment methods favoured in the research units. However, the majority tended to base their assessment on assignment work alone or in a combination of assignments, class performance and an exam. A glance at the web outlines for these various units suggests a mixed assessment regime including a series of exercises, assignments, research assignment, final exam, exercises, small group presentation, class participation, skills assignment (includes computer exercises throughout the year), research assignment, final exam, reflective essay, research essay, class assessment, ethics, teamwork exercise, group research topic, oral presentation, class tests, assignment and short presentation.

Table 5

What methods of assessment are used in the research training component?

|

Method

|

Frequency

|

|

Assignment only

|

20

|

|

Quizzes only

|

1

|

|

Examination only

|

1

|

|

Assignment and examination

|

7

|

|

Class performance

|

2

|

|

Assignment and class

performance

|

5

|

|

Quizzes and exam

|

1

|

|

Total

|

37

|

Skills levels are notoriously difficult to examine. It is also very difficult to differentiate between student skills levels. It would have been useful to have received more information from the survey regarding this aspect of the courses. Most respondents are favouring assessment based on assignments only. This is an ideal way to examine research outcomes but, unfortunately, it can be open to abuse through over-collaboration amongst students. It also does not necessarily effectively examine research methodology or process. On the other hand, exams are extremely awkward methods for gauging skills levels, although there has been some experimentation with practical research exams in the past. Combinations of methods would seem to address some of the more “thorny” issues regarding both these approaches.

There have always been difficulties associated with implementing the research units. Figures 9 and 10 set out the teaching staff responses. In regard to undergraduate units, teachers identify difficulties in motivating students and in high teacher-student ratios. Time needed for preparation of research exercises (including library research exercises) and workbooks, and for constant updating of these resources for workshops can prove difficult, as can dealing with varying competency rates amongst students in the one class. The responses demonstrate that the last two factors are the ones most likely to prove challenging for those teaching the postgraduate cohorts.

Figure 9

What do you perceive to be the three main difficulties associated with teaching legal research to undergraduates?

Key:

1 – motivating students

2 – gaining faculty support

3 – attracting qualified staff

4 – teacher-student ratios

5 – lack suitable teaching areas

6 – lack hardcopy resources

7 – lack computers

8 – preparation and updating time for workshops

9 – constant changes to electronic resources

10 – varying competency rates amongst students

11 – other

Database licensing problems were included as a choice for this question, but no respondents placed this as one of the three main difficulties encountered in teaching the research subjects.

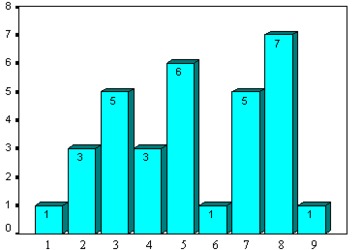

Figure 10

What do you perceive to be the three main difficulties associated with teaching legal research to postgraduates?

Key:

1 – teacher-student ratios

2 – lack teaching areas

3 – lack hard copy resources

4 – lack computers

5 – preparation and updating time for workshops

6 – database licensing problems

7 – constant changes to electronic resources

8 – varying competency rates amongst students

9 – other

The responses to the questions in Figures 9 and 10 relate well to another question on the survey. This asked whether the respondents would like to see specific improvements to the courses. The responses seemed to fall into a few categories. One group expressed the need for better resources, particularly in terms of a designated computer teaching laboratory and better teaching resources. They felt that the library could be better utilised for research teaching and a more hands-on approach taken to the unit. Another theme was the nature of the teaching workload with the research units. One respondent commented on the need for “[f]aculty recognition of labour-intensive nature of these units. Harder than teaching content unit.” Another commented that “[s]tudents need feedback on performance. More teaching credit [should be] allowed.” There was also recognition of the need for integration and reinforcement of the skills at a later year level: “Greater integration of techniques taught into other courses, or else the skills atrophy” and “Need research in all 4 yrs of degree”. Thus the themes of adequate resourcing of the units, heavy teaching workloads and the need for reinforcement and capstone units throughout the degree are recurring.

One difficulty identified in previous surveys was the tendency for research units to be changed constantly, with a consequential additional preparation time burden on those teaching them. Legal research materials tend to change every year in any case, so any change in format doubles the time taken to prepare materials. The results for this aspect of the survey were very encouraging in that they suggest that the courses are “settling down” and becoming more established parts of the curriculum. Despite this, the respondents are still commenting on the heavy preparation and updating times for the workshops as being major difficulties associated with the units.

Figure 11

How long has this subject been offered in its present format?

At least seven respondents reported that more changes were being considered for 2003. These included new teaching techniques, particularly as regards electronic delivery; new later year compulsory units; and integration of research skills training with other first year units.

Not surprisingly, there has been a gradual recognition of a need for skills reinforcement later in the law degree. This is reflected in the survey responses. So, as well as the compulsory first year research curriculum, six schools reported that research was compulsory in two or more years. This development makes good sense considering the rate of change in legal research sources over the years of the law degree in addition to the need for a “capstone” course to reinforce earlier skills training. It would make excellent sense to see this trend towards the inclusion of later year research skills updating and development units continue.

Aligned with any change such as this is the need for a coordinated approach to the inclusion of research skills in the degree. This is to ensure minimal duplication and ensure incremental skills development. As an example of ways of approaching this issue, QUT law school appointed a Director of Legal Research and Writing in courses in the mid 90s. The situation has now changed again and the Assistant Dean, Teaching and Learning has an umbrella role in relation to the embedding of all skills in the law degree. Other schools are also aware of this need for coordination.52

Unfortunately, there seems to be only a modest recognition of the need for non-doctrinal research methodologies being included in research training. How should this be accommodated? The options at present are a social science elective within the curriculum or the addition of basic segments to the present research courses. The difficulty lies in the total number and extent of possible options available for those students wishing to engage in non-doctrinal research methodologies. These of course include policy research, but also all the individual methodologies encompassed within the broader areas of qualitative and quantitative research. As well, there are the various electronic research packages to master, including, for example, EndNote, NVivo and SPSSX. Any such course still may not cover methodological research issues raised in the current interplay of medical research, DNA, bio-ethics and the law. All that can reasonably be accomplished in a compulsory course is to introduce the recognised non-doctrinal methodologies at a basic level. This certainly needs to occur by the time the students complete the upper level and postgraduate courses.

When combined with research, legal writing skills do not seem to be achieving the required number of teaching hours commensurate with the importance of excellent communication skills for lawyers. This is especially the case where legal research is merely a component of another compulsory unit. In this instance, the emphasis necessarily becomes an attempt to cover all the required research techniques and therefore communication misses out. Of course, the survey results do not take account of legal drafting units being offered in the degrees, or indeed of writing components in other units. However, the common view among law teachers would seem to be that the students should have good language and writing skills when they begin a law degree. If so, then the law curriculum should only need to focus on encouraging adherence to set citation styles and to teaching legal writing forms specific to the discipline such as letters to clients, barristers’ opinions, client newsletter articles or internal office research memorandums. Formative assessment can encourage good writing style. Bad writing can be penalised in a minor way through summative assessment criteria included within research assignments, for example. Unfortunately, this may not be sufficient. Perhaps there may be a case for more rigorous testing early in the degree to gauge competence. These issues are necessarily very sensitive because of the numbers of international students enrolled in law degrees and the great diversity of the current student body including the equity special entry cohort.53

Overall, there has been a transformation in the curriculum response to legal research in the last fifteen years in Australia. However, the impetus for change seems to have slowed in the last five years and there is still need for improvement. Teaching is uneven between the various law schools. Many schools have not taken notice of the real need for inculcating research and updating skills in their graduates especially when taking account of government agendas and the electronic revolution affecting research methods. There are also still reports of fundamental difficulties such as student motivation, high teacher student ratios and wide disparities in capabilities in the student population, especially at the postgraduate level. These are the same issues that were raised in 1991. This all points to a need for better understanding by the law school administrators of the heavy load that skills’ teaching places on academics. This includes extra preparation time, updating and marking of continuous assessment tasks. If we are looking for a blueprint for the future, we must endeavour to direct attention to these areas, along with the need for incremental skills training, recognition of the importance of understanding non-doctrinal methodologies and the ever-present need to nurture communication skills in law students.

[*] Senior Lecturer, QUT Faculty of Law. This article is based on a paper presented at the Legal Research Communications Interest Group session, Australasian Law Teachers Association Conference, Murdoch University, Western Australia, 2002. Tamara Walsh was the research assistant working on this project and Dr Helen Gustafson was the statistical consultant.

[1] See various studies including D Pearce et al, Australian Law Schools: A Discipline Assessment for the Commonwealth Tertiary Education Commission (Canberra: AGPS, 1987), Vol 1; F Zemans and V Rosenblum, “Preparation for the Practice of Law – The Views of the Practicing Bar” (1980) 1 American Bar Foundation Research Journal 1 at 3.

[2] T Hutchinson, “Legal Research Courses: The 1991 Survey” (1992) 110 ALLG Newsletter 87.

[3] S Christensen and S Kift, “Graduate Attributes and Legal Skills: Integration or Disintegration?” [2000] LegEdRev 8; (2000) 11 (2) Legal Education Review 207 at 213.

[4] Mayer Committee, Employment-related Competencies: A Proposal for Consultation (Melbourne: Owen King, 1992); Mayer Committee, Putting General Education to Work: The Key Competencies Report (Melbourne: Australian Education Council and Ministers of Vocational Education, Employment and Training, 1992).

[5] Id at 14.

[6] The Review Committee on Higher Education Financing and Policy (Chair Roderick West), Learning for Life (1998) 47; see http://www.dest.gov.au/archive/highered/hereview/toc.htm (viewed 7 October 2004).

[7] Dr D Kemp, New Knowledge, New Opportunities: A Discussion Paper on Higher Education Research and Research Training (Canberra: Commonwealth Department of Education, Science and Training, June 1999); see http://www.dest.gov.au/archive/highered/otherpub/greenpaper/index.htm (viewed 7 October 2004).

[8] Dr D Kemp, Knowledge and Innovation: A Policy Statement on Research and Research Training (Canberra: Commonwealth Department of Education Science and Training, 1999); see http://www.dest.gov.au/archive/highered/whitepaper/default.asp (7 October 2004).

[9] New Knowledge, New Opportunities, supra note 7 at 6.1.

[10] M Gallagher, “The Challenges Facing Higher Education Research Training” in M Kiley and G Mullins (eds), Quality in Postgraduate Research: Making Ends Meet (Proceedings of the 2000 Quality in Postgraduate Research Conference, Adelaide, April 13-14) 9 at 10 (as presented by J Gordon).

[11] Commonwealth Department of Science Education and Training, Learning for the Knowledge Society: An Education and Training Action Plan for the Information Economy (Australian National Training Authority, 2000) 82; see http://www.dest.gov.au/schools/publications/2000/learning.pdf (viewed 7 October 2004).

[12] Commonwealth Department of Education Science and Training, “Higher Education at the Crossroads: A Review of Australian Higher Education”, Higher Education Review Process: Issues Paper, Striving for Quality Learning, Teaching and Scholarship (Canberra: Department of Education Science and Training, 2002) 31; see http://www.backingaustraliasfuture.gov.au/review.htm (viewed 7 October 2004).

[13] P Kearns, NCVER Generic Skills for the New Economy: Review of Research (Canberra: Australian National Training Authority, 2001); see http://www.ncver.edu.au/publications/602.html (viewed 7 October 2004).

[14] Kearns, id at 76.

[15] Dr B Nelson, Higher Education at the Crossroads: A Review of Australian Higher Education (Canberra: Commonwealth Department of Education Science and Training, 2002); see http://www.backingaustraliasfuture.gov.au/review.htm (viewed 7 October 2004).

[16] Id at 1.

[17] Information Literacy Competency Standards for Higher Education (Chicago: Association of College and Research Libraries, 2000); see http://www.ala.org/ala/acrl/acrlstandards/informationliteracycompetency.htm (viewed 7 October 2004).

[18] Definition from American Library Association, Presidential Committee on Information Literacy Final Report (Chicago: American Library Association, 1989); see http://www.ala.org/ala/acrl/acrlpubs/whitepapers/presidential.htm (viewed 7 October 2004).

[19] The Boyer Commission on Educating Undergraduates in the Research University, Reinventing Undergraduate Education: A Blueprint for America’s Research Universities (Stony Brook: State University of New York, 1998); see http://naples.cc.sunysb.edu/Pres/boyer.nsf/ (viewed 7 October 2004).

[20] A Bundy (ed), Australian and New Zealand Information Literacy Framework: Principles, Standards and Practice (2nd ed, Adelaide: Australian and New Zealand Institute for Information Literacy, 2004) 18; see http://www.caul.edu.au/info-literacy/InfoLiteracyFramework.pdf (viewed 7 October 2004).

[21] Id at 20.

[22] N Cuffe, “Information Literacy and Legal Research” (1999) 7(1) Australian Law Librarian 57.

[23] C Bruce, The Seven Faces of Information Literacy (Adelaide: Auslib, 1997) 7.

[24] C Wren and J Wren, “Reviving Legal Research: A Reply to Berring and Vanden Heuvel” (1990) 82 Law Library Journal 463.

[25] T Hutchinson, Researching and Writing in Law (Sydney: Lawbook Co, 2002).

[26] M Fitzgerald, “What’s Wrong with Legal Research and Writing? Problems and Solutions” (1996) 88(2) Law Library Journal 247 at 271.

[27] Commonwealth Tertiary Education Commission, Australian Law Schools: A Discipline Assessment for the Commonwealth Tertiary Education Commission (Canberra: AGPS, 1987).

[28] C McInnis and S Margison, Australian Law Schools after the 1987 Pearce Report (Canberra: AGPS, 1994).

[29] S Christensen and S Kift, supra note 3 at 208.

[30] American Bar Association, Legal Education and Professional Development – An Educational Continuum (Chicago: ABA, 1992).

[31] Australian Law Reform Commission, Managing Justice: A Review of the Federal Civil Justice System, Report No 89 (Canberra: AGPS, 1999) at para 2.21; see http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/other/alrc/publications/reports/89/ (viewed 7 October 2004).

[32] R Johnstone and S Vignaendra, Learning Outcomes and Curriculum Development in Law: A Report Commissioned by the Australian Universities Teaching Committee (AUTC) (Canberra: Department of Higher Education, Science and Training, January 2003) 133; see http://www.autc.gov.au/projects/completed/loutcomes_law/split_pdf.htm (viewed 7 October 2004).

[33] N Cuffe, “Embedding Graduate Attributes in Law: Reflections of a Law Librarian Seconded to a Teaching and Learning Grant Project” (2001) 9(4) Australian Law Librarian 314 at 315; and see Queensland University of Technology, Manual of Policies and Procedures, Chapter C1.3 Graduate capabilities; see http://www.qut.edu.au/admin/mopp/C/C_01_03.html (viewed 7 October 2004); S Christensen and N Cuffe, “What Lawyers Need to Know v What Lawyers Need to Do (2002) Jan/Feb Proctor 18; Christensen and Kift, supra note 3.

[34] Cuffe, supra note 33 at 318.

[35] Christensen and Cuffe, supra note 33 at 19.

[36] T Hutchinson, “Legal Research Courses: The 1991 Survey” (1992) 110 ALLG Newsletter 87.

[37] Id. These issues are still being highlighted by the respondents to the most recent survey in 2002.

[38] E Barnett, “Legal Research Skills Training in Australasian Law Faculties: A Basic Overview. The Issues” (Paper presented at the 50th Anniversary Conference of the Australasian Law Teachers Association 1995); see http://www.austlii.edu.au/cgi-bin/disp.pl/au/special/alta/alta95/barnett.html (viewed 7 October 2004).

[39] Subscribe to this list by emailing the Interest Group Convenor at t.hutchinson@qut.edu.au.

[40] However, it is never wise to assume that hard-earned expertise will prevail against economic rationalism so this should be included in future surveys.

[41] DEST, supra note 12 at 48.

[42] Id.

[43] Includes “separate compulsory subject” plus “segment of a compulsory subject”.

[44] Some universities have more than one subject included.

[45] Not all respondents answered this question.

[46] Not all respondents answered this question.

[47] Not all respondents answered this question.

[48] Not all respondents answered this question.

[49] Respondents from the 25 universities identified 27 subjects for the purposes of this question.

[50] All subjects over all universities. Each subject or unit counted once.

[51] Each subject or unit counted once (n=34 units/subjects).

[52] A coordinator’s position was certainly within the plans being put forward at the University of Western Australia in 1999; M Flynn, “Legal Research Skills: What are they? When should they be taught? How can they be taught? And what about the other 34 skills that law graduates frequently use?” (paper presented at the ALTA Conference Legal Research and Communications Interest Group, NZ, 1999).

[53] This view on legal writing is in contrast to that demonstrated in the US legal education context where heavy emphasis seems to be placed on writing at the expense of research in the Legal “Writing” courses. This difference could arguably be based on the different legal contexts and especially on the prevalence of use of written briefs in the US courts.

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/LegEdRev/2004/4.html