Current Issues in Criminal Justice

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

Current Issues in Criminal Justice |

|

Crime, Policing and (In)Security: Press Depictions of Sydney’s

Night-Time Economy

Phillip Wadds[*]

Abstract

The night-time economy is a space of significant anxiety and concern. Recent high-profile incidents of alcohol-related violence in Sydney, Australia, have exacerbated community fears about the risks associated with the city after dark and placed the regulation and policing of nightlife in the media spotlight. This article is based on a content analysis of newspaper representations of Sydney’s night-time economy and the policing and security of nightlife settings from 1996 to 2012. It argues that public police and private security are portrayed in contrasting ways. Print media reflects public ambivalence and insecurity by representing the private security industry as unruly and violent, and with links to criminality. In contrast, media portrayals of New South Wales Police reflect the conscious efforts of an increasingly media-aware police organisation to protect its public image and reinforce its occupational legitimacy.

Keywords: night-time economy – nightlife – policing – plural policing –

private security – media – news – image-work – Sydney

Introduction

In the last two decades, restructuring post-industrial cities have focused on a reshaping of the urban night away from its traditional depiction as a sphere of crime and danger. The emergence of what is now known as the urban night-time economy (‘NTE’) was central to this transformation. The NTE, as a concept, refers to the range of leisure-based activities and experiences connected with after-dark socialising and entertainment (Rowe et al 2008). Researchers have suggested that the urban centres that were developed to host the NTE are the product of neoliberal strategies, such as market deregulation and the promotion of private investment, that claim to provide the solution to dormant economies and the crisis of public sector funding (Harvey 1989; Hughes 1999).

Advocates view the NTE as a sphere with the potential to arrest the decline of many inner-city precincts and to create new forms of public sociability and inclusion in regenerated and reinvigorated urban spaces (see Bianchini 1995; Landry et al 1995). Indeed, Bianchini (1995), the first to coin the term ‘night-time economy’, argued that the creation of vibrant, inclusive and culturally diverse night-time entertainment precincts would have the combined effect of providing a solution to issues of crime and personal safety in derelict sites, as well as rejuvenating depressed city centres by mobilising social and cultural engagement in unused urban spaces. In this vision, inclusiveness and cultural diversity would engender the relaxed pursuit of ‘civilised’ after-dark leisure with minimal social conflict, restricted demands on police time, and the enhancement of an underlying sense of public safety by the provision of expanded private security services.

These processes of urban change with expanded commercial nightlife have shaped the planning and promotion of most cities that make claim to a ‘global’ cosmopolitan or culturally significant status. Sydney is the Australian city where this title has been most fervently pursued. The city’s urban NTE is a place of both real and imagined risk, where apparent freedom and transgression are ostensibly linked, and where the regulation of leisure and collective drinking is diffused throughout a network of state and private actors. There are public policy contradictions in ‘policing’ an expanded NTE that is often linked to social disorder, but which also provides a significant source of income for the state economy and private sector interests. Government and political ambivalence regarding the role and value of alcohol and associated leisure is reflected in the development and adoption of shifting strategies regarding policing and regulation. The frequent influence of the media on the public and political agenda has made the application of stable regulation more difficult, and it has also limited policing and security strategy. Furthermore, in this occupational domain the role of both public and private policing bodies is ambiguous and in constant flux.

This article aims to explore media depictions of policing in urban nightlife precincts to ascertain what impact such representations have on occupational legitimacy and broader processes of pluralisation occurring in the policing of these spaces. It begins with a general discussion of media treatment regarding urban nightlife before moving on to more targeted analyses of the media representation of public police and private security operating in Sydney’s NTE.

Crime, media and nightlife security

Fishman’s (1978) seminal article ‘Crime Waves as Ideology’ referred to the power that public consciousness holds over the political and social agenda in relation to crime and safety. He observed the influence of various media forms in producing a politics around crime that fundamentally alters perceptions of public safety and security. Similarly, Hall et al (1978) argued that media-driven moral panics can serve as reinforcement for repressive state-based policing initiatives and authoritarian politics more broadly. While these works were written over 30 years ago, their messages resonated at the end of the last century and in more recent years (see also Hogg and Brown 1998; Critcher 2003; Potter and Kappeler 2006; Poynting and Morgan 2007).

In an age of expanding media platforms and ‘new media’, the general public is exposed to more ‘news’ than ever before (Lee 2007; Newman, Dutton and Blank 2011). In relation to crime and crime news, it appears that public interest has grown alongside the range of media through which information is channelled. Crime, in ‘factual’ and fictional form, now holds a significant place in all popular media. Indeed, Reiner, Livingstone and Allen (2000) documented that crime news has increased dramatically and has become a highly valued “commodity” in contemporary times. The public fascination with crime and crime news has led to a representation of offending that often contradicts official crime statistics (Fishman 1978; Ditton and Duffy 1983; Smith 1984; Reiner 1997; Howitt 1998; Potter and Kappeler 2006).

Since the mid-1970s, researcher views of the effects of media on fear of crime have been mixed (Heath and Gilbert 1996; Ditton et al 2004). Nevertheless, the apparent over-representation of crime in the media, particularly crimes of a violent and personal nature (Ditton and Duffy 1983; Williams and Dickinson 1993; Reiner 1997; Lundman 2003; Potter and Kappeler 2006), is thought to influence fear of crime (Cornaglia and Leigh 2011). Research indicates a link between media representations of crime, particularly those involving interpersonal violence, and a decrease in perceptions of public safety and a rise in local fear of victimisation (Chiricos, Eschholz and Gertz 1997; Potter and Kappeler 2006; Ericson 2007; Lee 2007; Cornaglia and Leigh 2011). In relation to the making of news, Hall et al (1978:57) noted that ‘the media do not themselves autonomously create news items; rather they are “cued in” to specific news topics by regular and reliable institutional sources’. Consequently, the media act as ‘secondary definers’ of news events, reproducing information provided from primary sources and frequently translating/manipulating them into popular stories (Barker 2003) with high news value (Jewkes 2015). Journalists writing on police and the NTE are part of this process (Ericson, Baranek and Chan 1989).

It is likely that a disproportionately high focus on certain crime in the news can inform a simplistic and punitive law and order view of offending, punishment and prevention. This perception is reinforced by the reported views of a number of ‘primary definers’ who add further weight to law and order claims that tap into populist views about crime (Hogg and Brown 1998:18; see also Hall et al 1978). These actors sit atop the hierarchy of credibility (Becker 1967), a privileged position in mainstream media that can enhance the legitimacy of the different parties they choose to endorse. While, historically, populism does not have a ‘pre-ordained ideological content’ (Quilter 2014:7), in more recent times it has come to be associated with conservative politics and can be understood as a political doctrine that claims to represent the views and sentiment of the dominant population in a given place (Hogg 2013). These findings have significance for the analysis of media depictions of policing and security within the NTE, as for most people it is the media that provides the central locus of discussion regarding urban crime and safety after dark. As found from this media analysis, the ‘commonsense’ regarding Sydney nightlife is that it is typically the domain of disorderly, intoxicated and poorly supervised young revellers.

The Sydney press study

This article is based on a content analysis of Sydney’s NTE and the ‘policing’ of Sydney’s nightlife settings in two local daily newspapers from 1996 to 2012. It studied depictions of both public and private policing to reflect upon the contradictory governance in relation to the NTE and to investigate discourses that relate to the regulation and policing of this domain. The underlying approach of content analysis involves the application of a coding schema to texts in order to count instances of given categories or themes within data (Riffe et al 2008). In this case, basic counting and assessment of article numbers, frequency, prominence in text and imagery was employed to gain insight into the salience of particular media themes concerning the condition of Sydney nightlife and its policing.

Press items were subjected to content analysis with the focus on a discursive construction of meaning (Minichello et al 1999; Philips and Hardy 2002; Fairclough 2003; Richardson 2007). This press study formed one part of a broader mixed methods ethnographic study including a combination of participant observation of key nightlife sites (see Wadds 2013; Tomsen and Wadds 2015) and semi-structured, in-depth, interviews (Wadds 2013) with informants engaged in the policing and security sectors operating in the NTE of Sydney.

The high frequency and prominence that accounts of night-time violence and disorder receive in the general media and print news suggest serious risks to personal safety and security. Although it is the case that in the NTE an intoxicated release from the routines of contemporary life often results in nuisance, disorder and assaults, media depictions of more extreme violence than minor public disorder offences appear to play a significant role in shaping public opinion and occasional policy change. Reports about disruptive night leisure were found with regularity over the timeline of the press analysis conducted by the author, with high news value placed on the presentation of graphic images and text concerning violence. For example, this analysis uncovered a significant increase in reporting on the topic of ‘drinking and violence’ between 1996 and 2012. During this period, there were 623 articles written in the two major Sydney-based newspapers subject to study. The Sydney Morning Herald (‘SMH’) and The Daily Telegraph (‘DT’) represent respectively Sydney’s main broadsheet and tabloid newspapers.

If taken as an indicator of public and political concern, the increase in articles does not sit well with official crime figures for these same years that provide a breakdown of the number of incidents of alcohol-related assaults in inner city Sydney. Although official crime statistics are often limited by a lack of reporting and recording (Weatherburn 2011), data from the New South Wales Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research (‘BOCSAR’) suggests that per capita rates of alcohol-related violence and disorder in parts of inner city Sydney (including Kings Cross) have fallen or remained stable over the last decade.

Historically, broadsheet newspapers have been said to report the news more ‘objectively’ than tabloids. Objectivity in relation to the media usually refers to a focus on corroborated ‘facts’. Broadsheet newspapers such as the SMH have historically claimed to favour news stories that are supported by ‘expert’ opinion rather than less reliable sources. This focus promotes greater impartiality than tabloid newspapers that often present news with a more obvious level of sensation. Thus, in Sydney’s case, the key tabloid daily is sometimes vernacularly referred to as ‘the Daily Terror’. However, one important and recurrent observation throughout the literature on media effects is that news articles, including those presented in broadsheet newspapers, have become more sensational or ‘tabloid’ over the last three decades in their search for audiences (Blumler and Gurevitch 1995; Grabe et al 2001; Uribe and Gunter 2004; 2007). This broad ‘tabloidisation’ of news media has influenced news selection and production methods and has often detracted from the apparent objectivity of the news (Uribe and Gunter 2004, 2007) and influenced perceptions of particular topics.

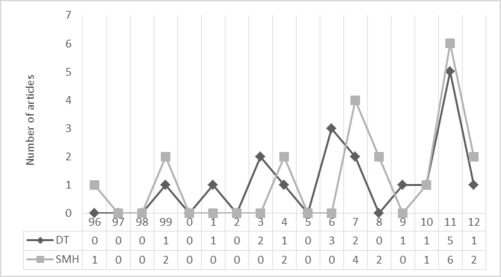

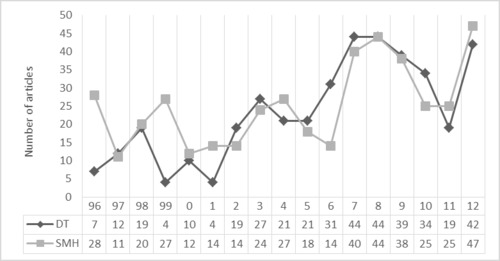

The results of the press analysis shown in Figure 1 clearly indicate the 17-year increase in reports of drinking and violence with notable peaks in 2008 (when the New South Wales (‘NSW’) state government and police declared a full ‘war’ on drunken violence) and 2012 (coinciding with the controversial killings of two young revellers in Sydney’s Kings Cross). This overall increase and key peaks can be seen in the reports for both newspapers. Similar peaks can also be seen in Figures 2 and 3, which map the number of articles from both papers concerning ‘private security and pubs’ and ‘police and alcohol’.[†]

Figure 1: Number of articles by year and publication: ‘Drinking and violence’

It is arguable whether or not the rise in articles written in the broadsheet SMH over the study period was a reflection of a tabloidisation process or a shift in interest towards this topic with an overt NSW state political focus. The sharp increase in articles between 2011 and 2012 in the SMH included accounts stressing the moral legitimacy of the victim as naïve innocents killed in the violent nightlife of Kings Cross, with a flow on professional middle-class family campaign and comment from legal figures regarding proposed and adopted reforms to regulation of nightlife and punishment of violent offenders.

On the other hand, the tabloid DT appears to have had a much higher focus on the 2008 ‘war on alcohol-related violence’ as an episode with a discursively more simplistic opposition between public authority and the behaviour of intoxicated ‘thugs’.

Figure 2: Number of articles by year and publication: ‘Private security and pubs’

Figure 3: Number of articles by year and publication: ‘NSW Police and alcohol’

Quite unexpectedly, the number of reports in the broadsheet SMH exceeded those of the tabloid DT in seven of the 17 years in articles written on the subject of ‘private security and pubs’ and in eight years in articles written on the subject of ‘police and alcohol’.

Despite this difference in reporting between the two newspapers, a general tone of police-positive/security-negative persisted for both newspapers. This was particularly noteworthy for the SMH when it entered into a phase of heightening interest in the political ramifications of the form and regulation of Sydney’s NTE.

Public police in the press: The search for legitimacy in the NTE

Reiner (2010:201), discussing the changing nature of the police-public relationship, stated that ‘public faith in the police is tentative, volatile, contradictory, and brittle, and has to be negotiated case by case’. Media depictions of crime, and the inability of police to control it, have highlighted what Garland (1996:448) called the ‘myth of sovereign crime control’ and have led to a questioning of whether police have the ability to satisfy the broadest public demands for order, safety and security in contemporary society. It is evident that this ‘crisis’ in policing has required the police to utilise high-profile media campaigns to reinforce their legitimacy. Alongside the expanded public interest in more crime news, contemporary police organisations have been subjected to increased public visibility (Mawby 2002). The police inability to address all form and incidents of crime and civil disorder could potentially erode levels of public confidence. Any possible decline in confidence would create a very significant problem because, as Lee (2011:2) suggests, ‘to be effective, policing requires the ongoing support, consent and ongoing cooperation of the public. Such public support and cooperation rests upon the legitimacy of the police organisation’.

The representation of contemporary nightlife uncovered by this press analysis often stressed issues of violence and disorder alongside suggestions that public safety and security were not being satisfied by traditional policing services. In some examples, public policing agencies were depicted as being fully incapable of controlling unruliness and crime at night. Articles such as the following reflected this sentiment:

• ‘Call in Clayton’s Cops’ (Lamont 1999)

• ‘Thugs Lay it on the Line: Train Security is Being Fast-Tracked ... and Night Travellers Know Why’ (Walker 1999)

• ‘Police Get Blame for Rise in Bar Violence’ (Baker 2008a)

• ‘Private Army of the Cross’ (Howden and Ralston 2011)

• ‘Kings of the Cross Take Matters into Their Own Hands’ (Howden 2011)

• ‘The Real Crime in Kings Cross is Police Inaction’ (Devine 2012).

Here, public policing services were portrayed as ineffective in relation to urban nocturnal safety. The article ‘Call in Clayton’s Cops’ referred to the need for private security to be introduced because ‘the police can't be everywhere and most government statutory authorities have a good reason to have [special constables]’ (Lamont 1999).[‡] More recently, the articles ‘Private Army of the Cross’ (Howden and Ralston 2011) and ‘Kings of the Cross Take Matters into Their Own Hands’ (Howden 2011) described new initiatives undertaken by the NSW state government, local council, local liquor accords and key stakeholders in Sydney’s Kings Cross nightlife precinct. Here, private security guards were being employed to police public space in an effort to curb alcohol-related street violence and disorder.

The media reports oscillated between censure and a tone of sympathy in relation to the activity of public police. In Howden and Ralston’s (2011) article, the leader of one security team claims that police have informed him ‘they could not do it (police Kings Cross) without us’. Howden’s (2011) article takes this position further, insisting that a local Licensing Accord Association was unable to rely on NSW Police to maintain law and order. Furthermore, members of the Accord were reported as claiming that the increased demands being made on licensees in relation to the conduct of patrons on their premises are not being supplemented with adequate support from the police (Howden 2011).

Such reports were typical of those found throughout the analysis. They appear to promote a sense of social vulnerability by highlighting the limited resources of public policing agencies that are arguably symptomatic of the neoliberal focus on free markets, privatisation and cuts to service provision by the state (Amin and Malmberg 1995; Jessop 1997; 2002 Fourcade-Gourinchas and Babb 2002; Harvey 2005). Under the direction of neoliberalism, state institutions have been ‘hollowed out’ (Newburn 2001; Jessop 1997, 2002) and assumed greater audit and regulatory capacities at the expense of public service delivery (Harvey 2005). Thus, unsurprisingly, such reports also foster an interest in a further privatisation of policing/security of a sort that disregards the trouble between police and security that such pluralisation can create. While Mazerolle and Ransley (2005) suggest that civil involvement in policing is instrumental to an ultimate shared policing goal, in the context of a NTE that is full of inherent distrust and tension between police and security, major extension of public surveillance operations by non-police are resented by those officers who see such developments as akin to ‘vigilantism’. Indeed, following the introduction of a private security force employed to police public space in Kings Cross, Scott Weber, President of the NSW Police Association, stated, ‘[A]n untrained, poorly equipped and unaccountable private security gang is no substitute for a professional police force’ (Howden and Ralston 2011). This official discomfort reflects mixed feelings about the occupational shift towards privatisation of this work, but says nothing about the issues of legality that are more pressing for the greater public.

The reported challenges for public police in relation to control of nightlife went even further and have also reinforced the industry push for more use of private security. In current public policy, the focus is on ‘risk-based’ crime prevention in dealing with problems of crime and disorder. Privatised forms of security are seen as a legitimate solution to the fiscal crisis that grips many of the state governments across Australia. By encouraging private individuals to take up the mantle of security provision, the state is acknowledging its inability to provide effective governance (Garland 1996). Given evidence linking police efficacy to institutional legitimacy (see Hough et al 2010), it is likely that this pluralisation of policing (see Loader 2000; Jones and Newburn 2002, 2006) at least partly undermines public confidence in the police.

Paradoxically, such transformations are also more broadly tied to long-term efforts to stifle police corruption in relation to nightlife. In Sydney, this critical public scrutiny of policing is compounded by the lasting legacy of negative images from the Wood Royal Commission (1994–97), which exposed the vice and corruption of Kings Cross Police officers concerning the regulation of nightlife venues. It is major scandals like this, alongside escalating fear of crime and public demands for improved safety, that have placed increasing pressure on the police to generate positive images in an attempt to bolster public confidence (Mawby 2002; Lee 2011; Lee and McGovern 2014).[§]

The NSW Police ‘brand’ and Operation Unite

The media, while drawing out many of the problems concerning police legitimacy, have also provided policing organisations with a valuable medium through which positive symbolic images of the police can be promoted (Lee and McGovern 2014). Indeed, it is argued by Lee and McGovern (2014) that this type of ‘simulated’ policing is seen by police as a legitimate form of policing. This process has been evident in NSW with the establishment and increasing growth of the Public Affairs and Corporate Communications Branch of the NSW Police (McGovern and Lee 2010; Lee 2011; Lee and McGovern 2014). This incorporates the Police Media Unit and is responsible for: media and issue management; proactive communications and marketing projects; oversight of media policy, corporate image and branding; and public relations work (NSW Police Force 2014). Lee (2011) suggests that the establishment of the NSW Police Media Unit and Public Affairs Branch was/is symptomatic of the need for police to be seen taking direct action against crime, and that it plays a key role in shaping the ‘corporate reputation’ of NSW Police. In controlling data and providing media training and expertise to the police hierarchy, the Media Unit ensures that police reports are delivered in a way that produces the most positive public image.

Regardless of research suggesting that police are increasingly undertaking their own image work through social media platforms (Ellis and McGovern 2015), this sort of symbiotic police and media relationship regarding reports of night-time and street danger from violence and crime has in fact developed over many decades. However, contemporary NSW Police organisational changes appear to have made this mutual closeness even more pronounced. Examples of this process include how police have responded to a number of public and media concerns regarding Sydney nightlife. In 2008, during a time of increased public anxiety about violence and disorder in Sydney’s NTE, the NSW Government, along with NSW Police, declared a ‘war’ on alcohol-related violence (Welch 2008a). Since this time, the NSW Police have engaged in high-visibility, targeted policing operations targeting on key nightlife hotspots. The largest of these operations, Operation Unite, was launched in December 2009 as ‘a blitz against drunken violence’. Alongside these operations, a new policing unit, the Alcohol Licensing Enforcement Command (‘ALEC’) was established, with the explicit task of driving down alcohol-related violence in NSW.

Operation Unite is a nationwide campaign against alcohol-related violence. Symbolically, the operation has become a cornerstone of police policy concerning alcohol-related offences in Sydney. Since 2008, NSW Police have frequently utilised the media to reassure the public that this ‘war on drunks’ is being won by the police and that alcohol-related violence and disorder will not be tolerated. NSW Police Commissioner Andrew Scipione, as the state spokesperson for Operation Unite, has faced television news cameras and released dozens of press releases concerning the success of police operations.

Operation Unite employs high-visibility street policing that aims to saturate nightlife precincts with police to prevent alcohol-related offences. According to a police media statement released on 11 May 2011, NSW Police arrested 2100 people, laying 3440 charges over three operations (NSW Police 2011). These figures included 640 arrests in December 2009, 737 in September 2010 and 723 in December 2010 with 1025 charges laid in December 2009, 1101 in September 2010 and 1314 in December 2010. These statistics reflect the nature of the operation, which is employed to offer positive public images of police control and order with a large crackdown on many low-level offences.

BOCSAR indicates that, since the inception of the NSW Government’s war on alcohol-related violence and the introduction of Operation Unite, recorded and well-publicised ‘liquor offences’, which may have a strong relationship with perceptions of public order, have dramatically increased. In 2007, prior to the state Government’s declaration of ‘war’ on alcohol-related violence, the number of recorded liquor offences in Sydney’s local government area (‘LGA’) was 1641. The following year, 2513 offences were recorded by BOCSAR, an increase of 53.1 per cent. Between April 2010 and March 2011, 3466 liquor offences were reported in the Sydney LGA, an increase of 111.2 per cent since 2007. While these ‘liquor offence’ statistics have dramatically increased over the period since the state Government’s declaration, more serious offences, including ‘assault — non domestic violence related’, most commonly associated with alcohol-related violence, have remained stable and show no significant rise over the same period (3980 incidents between April 2006 and March 2007, and 3952 between April 2010 and March 2011).

Despite police responses not focusing on levels of violence, which are the focus of most media attention, the hard-line approach taken by the police towards liquor offences has been a way to create positive imagery of police outcomes. In this sense, the police can be seen as engaging with public demands for increased action on disorderly nightlife, or ‘doing something’ as Lee (2011) put it. This approach favours street police action to reinforce police imagery. To some extent, engaging with very broad crime categories like ‘liquor offences’ can be a means through which this legitimacy is enhanced.

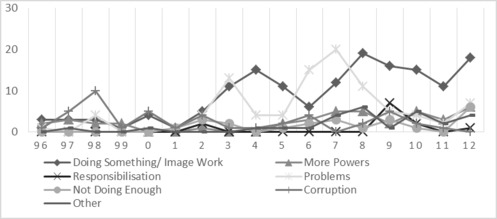

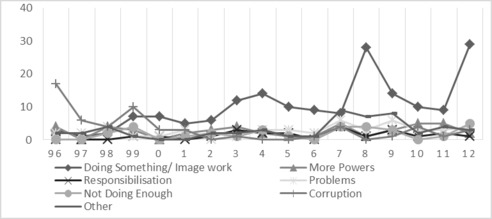

Figures 4 and 5 illustrate the trend toward ‘image work’ in police-media relations. Breaking down the period of analysis by theme (guided by analysis and selected based on prominence in press reports on police in the NTE) reveals that in the first four years of observation there was a heightened media focus on police corruption stemming from the then recently completed Wood Royal Commission. Indeed, drinking and nightlife featured prominently in these accounts of corruption, with much attention given to high levels of police drug and alcohol use both while on and off duty. Following this brief period of exception, the primary focus of media reports was on promoting positive imagery of the police. This has predominantly been achieved by presenting accounts of police action on issues relating to, and incidents of, alcohol-related violence. From the thematic analysis it is also possible to see evidence of the promotion of a law and order ‘commonsense’ (Hogg and Brown 1998) in frequent reports concerning problems relating to nightlife and a subsequent need for more police powers and a more responsible community.

Figure 4: ‘Police and alcohol’ thematic breakdown: Article number and theme by year,

The Daily Telegraph

Figure 5: ‘Police and alcohol’ thematic breakdown: Article number and theme by year,

The Sydney Morning Herald

Part of the prominent narrative surrounding police image work, particularly in relation to Operation Unite, has been an emphasis from senior police officials to project a traditional and punitive message concerning alcohol-related violence and disorder. Headlines such as the following provide examples of the way in which issues involving the police have been depicted in the media:

• ‘Operation Unite — Time’s up for Drunken Thugs’ (Fife-Yeomans 2009a)

• ‘Operation Unite Sends a Strong Message’ (Anon 2009)

• ‘RECLAIM OUR STREETS: Police across Two Nations Unite to Fight Violence’ (Fife-Yeomans 2009b)

• ‘Police Chief Calls for War on Drunks’ (Welch 2008a)

• ‘Police Get Tough on Alcohol’ (Welch 2008b)

• ‘Last Order for Drunken Aggression’ (Weber 2012).

Featured in each of these articles is a strong police narrative that provides reassurance to the public that proactive action is being taken to allay public concerns and anxieties about urban night-time disorder.

Private security in the press

While the police have (for the most part) successfully engaged with the media as a means to deliver positive imagery related to their service provision, private security providers have not and, as such, are presented in a wholly contrasting way. Though public policing agencies still occupy the key position in protecting populations from the threat of crime, it is private security that takes up much of the work that police no longer have the resources or desire to do. This process of ‘load shedding’ (Button 2002) is not new, but it has now seen private security increasingly take over or expand further into roles such as doorwork, venue control and guarding duties. Publicans, licensees and local councils/accords have turned to the private security industry to prevent violence and placate the concerns of authorities and local residents about violence and disorder in the NTE. Subsequently, the private security industry has now assumed the role of primary provider of safety and security in nightlife settings (Prenzler, Sarre and Earle 2007/8; Rigakos 2008; Sarre and Prenzler 2011; Wadds 2013). However, the pattern in Sydney’s NTE suggests very significant ambivalence in public and media discourse surrounding private security and its developing range of responsibilities.

High-profile incidents involving private security employees in Sydney’s NTE have placed the industry into the media spotlight and caused significant ruptures in public and police perceptions and confidence. These have included the death of Peter Dalamangas at Star City Casino in 1998, the death of David Hookes in 2004 (occurring in Melbourne but covered in high national publicity), the death of Wilson Duque Castillo following an altercation with venue security at a Kings Cross nightclub in 2010, and the bashing of Nicholas Barsoum at The Ivy entertainment complex in 2011. The press content associated with the above events suggests serious problems with ‘bouncer’ violence (see Clifton 2000; Hills 2011).

Images of heavily tattooed, hyper-masculine bouncers injuring patrons have been present throughout media coverage of the NTE. Violent bouncer behaviour is commonly linked with claims that the industry suffers a lack of appropriate regulation. The most important issue here is a matter of proportion rather than whether or not such violence is real — allegations of violence and criminal association among private security firms are supported by research that suggests that ‘doorwork cultures’ place a high value on violent/physical reputation and behaviour (Winlow 2001; Hobbs et al 2003; Tomsen 2005; Wadds 2013).

The headlines below encapsulate these themes and sentiments concerning bouncers that have emerged from the media content analysis:

• ‘Bouncer Regulations Inadequate, Says Professor, as Tragedy Sparks Call for Industry Crackdown’ (Jacobsen 2004)

• ‘Security Bounced from Cross Clubs’ (Kennedy 2009)

• ‘High Risk People in Security Industry’ (Dasey 2000)

• ‘Pub Violence Caused This Bloody Mess’ (Davies 2008)

• ‘Who Will Guard the Guardians?’ (Baker 2008b).

In ‘High Risk People in Security Industry’, Dasey (2000) claims that people employed in private security are more likely to be psychopathic than other ‘unskilled’ workers. The article is based on a purported ‘academic study’ and reports that the ‘security industry employs “significantly more” dangerous personality types than any other unskilled field because it offers them access to positions of power’. Furthermore, security workers have ‘a diminished sense of social responsibility and might commit violent and antisocial acts’ (Dasey 2000). These claims send a powerful message to target audiences and often fuel negative public perceptions of security staff (Wadds 2013).

Similarly, security staff are presented as engaging in retaliatory forms of collective action that results in brutal and premeditated violence. This violence is difficult for police to investigate because of a code of loyalty protecting security co-workers from criminal implication (Wadds 2013). The media has mainly focused on individual ‘bad apples’, those security guards whose rogue actions have resulted in serious injury or death. A particular feature of such accounts is the violent nature and history of the antagonists. In each of the above cases (Dalamangas, Hookes, Castillo, and Barsoum), some reference was made to the association between the security guards involved and their history of sporting violence (that is, boxing, martial arts or cage fighting). Such depictions focus on problematic individuals and are critically narrow, usually failing to engage in a discussion about the flawed regulations governing the industry.

Such negative media attention can, in exceptional circumstances, have a progressive influence in shaping public consciousness. This process was evident in the public outcry, and subsequent community and political mobilisation, which occurred throughout Australia following the death of David Hookes (see Wadds 2011, 2013). As a result, NSW legislation concerning the governance of the doorwork industry was reviewed and eventually amended, concluding with the introduction of the Security Industry Regulation Act 2007 (NSW).[**] The changes introduced by the new legislation have increased probity and background checks to ensure that persons with a recorded history of violence cannot enter the industry. Licensing processes have also been significantly altered, making very limited training programs more demanding. A probation period of one year has also been introduced ostensibly to ensure that those with no experience in the industry are subject to more rigorous operating standards. Nevertheless, flaws persist in the regulation, and the above case studies highlight the limits of the legislative and regulatory mechanisms that have so far failed to end abuse of the public and incidents of violence.

In recent decades, new and expanded urban NTEs have been promoted as emerging and desirable spaces of relaxed after-dark leisure and spending. Nevertheless, persistent issues of crime, public ambivalence and divisions between public police and private security limit this attractive vision. Media attention surrounding Sydney’s NTE is commonly directed to major incidents of alcohol-related violence in the city after dark. The author’s study of press reports confirms that this is the case in relation to both ‘broadsheet’ and ‘tabloid’ accounts of nightlife, policing and security. In relation to the policing and governance of nightlife, public police and private security are portrayed in contrasting ways that both approximate and are well removed from reality. To overcome the public apprehension about nightlife and to reinforce their own legitimacy, NSW Police has focused on high-visibility crackdowns and displays that are highly symbolic and in contrast with less dramatic (and less visible), but apparently more effective, modes of crime prevention and strategy, such as those introduced by local liquor accords. Police engagement in these high-profile ‘blitzes’ can be understood as part of the legitimising process to address community concerns about nightlife and thereby increasing public confidence.

Negative depictions of security partly undermine the very changes that are frequently touted as solutions to the contemporary crisis of urban security after dark. The media and political debate outlined in this article typically failed to engage fully in a more critical analysis of the industry and the regulations that govern it. Although private security employees are required to alleviate concerns about crime and interpersonal violence in the night-time economy, achieving this goal is hampered by the ubiquity of accounts that offer little faith in reform of the private security industry. There is a persisting uncertainty and doubt concerning the industry’s new position as key agents in the provision of personal safety and security in the city after dark. At one level, the negative representation of ‘bouncers’ engaging in aggressive and violent conduct can seem like appropriate accounts of serious episodes of misconduct and violence. At the same time, an overwhelming focus on such episodes and issues can exacerbate mistrust from both the public and from police, and detract from efforts to lift regulation within the security industry (see Sarre and Prenzler 2011).

Legislation

Security and Investigations Agents Regulations 2005 (Tas)

Security and Related Activities (Control) Amendment Act 2007 (WA)

Security Industry Regulation Act 2007 (NSW)

Security Providers (Crowd Controller Code of Practice) Regulation 2008 (Qld)

Security Providers (Security Officer — Licensed Premises — Code of Practice) Regulation 2008 (Qld)

Security Providers Regulation 2008 (Qld)

References

Amin A and Malmberg A (1995) ‘Competing Structural and Institutional Influences on the Geography of Production in Europe’ in A Amin (ed), Post-Fordism: A Reader, Blackwell

Anon (2009) ‘Operation Unite Sends a Strong Message’, The Sydney Morning Herald (online), 13 December 2009 <http://www.smh.com.au//breaking-news-national/operation-unite-sends-a-strong-message-20091213-kpxf.html>

Baker J (2008a) ‘Police Get Blame for Rise in Bar Violence’, The Sydney Morning Herald (Sydney), 24 April 2008, 3

Baker J (2008b) ‘Who Will Guard the Guardians?’, The Sydney Morning Herald (Sydney), 16 February 2008, 26

Barker C (2003) Cultural Studies: Theory and Practice, Sage

Becker HS (1967) ‘Whose Side Are We on?’, Social Problems 14(3), 239–47

Bianchini F (1995) ‘Night Cultures, Night Economies’, Planning Practice and Research 10(2), 121–6

Blumler JG and Gurevitch M (1995) The Crisis of Public Communication, Routledge

BOCSAR (2012) Drive-by Shootings by Suburbs: July 2007–June 2012, formerly available at <http://www.bocsar.nsw.gov.au/Lawlink/bocsar/ll_bocsar.nsf/vwFiles/Drive_by_shootings_LGA_Suburb.xls/$file/Drive_by_shootings_LGA_Suburb.xls>

Button M (2002) Private Policing, Willan Publishing

Chiricos T, Eschholz S and Gertz M (1997) ‘Crime, News and Fear of Crime: Toward an Identification of Audience Effects, Social Problems 44(3), 342–57

Clifton B (2000) ‘Why Casino Patron Died’, The Daily Telegraph (Sydney), 1 June 2000, 20

Cornaglia F and Leigh A (2011) ‘Crime and Mental Wellbeing’, CEP Discussion Paper No 1049, Centre for Economic Performance, London School of Economics

Critcher C (2003) Moral Panics and the Media, Open University Press

Dasey D (2000) ‘High Risk People in Security Industry’, The Sun Herald (Sydney), 29 October 2000, 43

Davies L (2008) ‘Pub Violence Caused This Bloody Mess’, The Daily Telegraph (Sydney), 29 May 2008, 13

Devine M (2012) ‘The Real Crime in Kings Cross is Police Inaction’, The Sunday Telegraph (Sydney), 15 July 2012, 41

Ditton J and Duffy J (1983) ‘Bias in the Newspaper Reporting of Crime News’, British Journal of Criminology 23(2), 159–65

Ditton J, Chadee D, Farrall S, Gilchrist E and Bannister J (2004) ‘From Imitation to Intimidation: A Note on the Curious and Changing Relationship between the Media, Crime and Fear of Crime’, British Journal of Criminology 44(4), 595–610

Ellis J and McGovern A (2015) ‘The End of Symbiosis? Australia Police-Media Relations in the Digital Age’, Policing and Society DOI: 10.1080/10439463.2015.1016942

Ericson RV (2007) Crime in an Insecure World, Polity Press

Ericson RV, Baranek PM and Chan JBL (1989) Negotiating Control: A Study of New Sources, University of Toronto Press

Fairclough N (2003) Analyzing Discourse: Textual Analysis for Social Research, Routledge

Fife-Yeomans J (2009a) ‘Operation Unite: Time’s up for Drunken Thugs’, The Daily Telegraph (Sydney), 11 December 2009, 12

Fife-Yeomans J (2009b) ‘RECLAIM OUR STREETS: Police across Two Nations Unite to Fight Violence’, The Daily Telegraph (Sydney), 19 November 2009, 1

Fishman M (1978) ‘Crime Waves as Ideology’, Social Problems 25(5), 531–43

Fourcade-Gourinchas M and Babb SL (2002) ‘The Rebirth of the Liberal Creed: Paths to Neoliberalism in Four Countries’, American Journal of Sociology 108(3), 533–79

Garland D (1996) ‘The Limits of the Sovereign State: Strategies of Crime Control in Contemporary Society’, British Journal of Criminology 36(4), 445–71

Grabe ME, Zhou S and Barnett B (2001) ‘Explicating Sensationalism in Television News: Content and the Bells and Whistles of Form’, Journal of Broadcasting and Electronic Media 45(4), 635–55

Hall S, Critcher C, Jefferson T, Clarke J and Roberts B (1978) Policing the Crisis: Mugging, the State and Law and Order, Palgrave MacMillan

Harvey D (1989) ‘From Managerialism to Entrepreneurialism: The Transformation in Urban Governance in Late Capitalism’, Geografiska Annaler 71(1), 3–17

Harvey D (2005) A Brief History of Neoliberalism, Oxford University Press

Heath L and Gilbert K (1996) ‘Mass Media and Fear of Crime’, American Behavioral Scientist 39(4), 379–86

Hills B (2011) ‘Bash Victim’s Widow Queries “Pack” Attack’, The Sunday Telegraph (Sydney), 9 January 2011, 33

Hobbs D, Hadfield P, Lister S and Winlow S (2003) Bouncers: Violence and Governance in the Nnight-time Economy, Oxford University Press

Hogg R (2013) ‘Punishment and “the People”: Rescuing Populism from its Critics’, in K Carrington,

M Ball and E O’Brien (eds), Crime, Justice and Social Democracy: International Perspectives, Palgrave Macmillan, 105–19

Hogg R and Brown D (1998) Rethinking Law and Order, Pluto Press

Hough M, Jackson J, Bradford B, Myhill A and Quinton P (2010) ‘Procedural Justice, Trust, and Institutional Legitimacy’, Policing 4(3), 203–10

Howden S (2011) ‘Kings of the Cross Take Matters into Their Own Hands’, The Sydney Morning Herald (Sydney), 1 August 2011, 1

Howden S and Ralston N (2011) ‘Private Army of the Cross’, The Sun Herald (Sydney), 20 March 2011, 19

Howitt D (1998) Crime, the Media and the Law, John Wiley and Sons

Hughes G (1999) ‘Urban Revitalization: The Use of Festive Time Strategies’, Leisure Studies 18(2), 119–35

Jacobsen G (2004) ‘Bouncer Regulations Inadequate, Says Professor, As Tragedy Sparks Calls for Industry Crackdown’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 21 January 2004, 6

Jessop B (1997) ‘The Entrepreneurial City: Re-Imaging Localities, Redesigning Economic Governance or Restructuring Capital’ in N Jewson and S MacGregor (eds), Transforming Cities: Contested Governance and New Spatial Divisions, Routledge

Jessop B (2002) ‘Liberalism, Neoliberalism, and Urban Governance: A State-Theoretical Perspective’, Antipode 34(3), 452–72

Jewkes Y (2015) Media and Crime, 3rd ed, Sage

Jones T and Newburn T (2006) Plural Policing, Routledge

Jones TT and Newburn T (2002) ‘The Transformation of Policing? Understanding Current Trends in Policing Systems’, British Journal of Criminology 42(1), 129–46

Kennedy L (2009) ‘Security Bounced from Cross Clubs, The Sun Herald (Sydney), 22 March 2009, 13

Lamont L (1999) ‘Call in Clayton’s Cops’, The Sydney Morning Herald (Sydney), 28 October 1999, 13

Landry C, Greene L, Matarasso F and Bianchini F (1995) The Art of Regeneration: Urban Renewal Through Cultural Activity, Comedia

Lee M (2007) Inventing Fear of Crime: Criminology and the Politics of Anxiety, Willan Publishing

Lee M (2011) ‘Force Selling: Policing and the Manufacture of Public Confidence?’, Proceedings from the Australian and New Zealand Critical Criminology Conference 2010, Sydney Law School, University of Sydney

Lee M and McGovern A (2014) Policing and Media: Public Relations, Simulations and Communications, Routledge

Loader I (2000) ‘Plural Policing and Democratic Governance’, Social and Legal Studies 9(3), 323–45

Lundman RJ (2003) ‘The Newsworthiness and Selection Bias in News about Murder: Comparative and Relative Effects of Novelty and Race and Gender Typifications on Newspaper Coverage of Homicide’, Sociological Forum 18(3), 357–86

McGovern A and Lee M (2010) ‘“Cop[ying] it Sweet?”: Police Media Units and the Making of News’, Australian and New Zealand Journal of Criminology 43(3), 444–64

Mawby RC (2002) Policing Images: Policing, Communication and Legitimacy, Willan Publishing

Minichiello V, Sullivan G, Greenwood K and Axford R (1999) Handbook for Research Methods in Health Sciences, Prentice Hall

New South Wales Police (2011) OPERATION UNITE: Facts and Figures, formerly available at <http://www.police.nsw.gov.au/news/latest_releases?sq_content_src=%2BdXJsPWh0dHBzJTNBJTJGJTJGd3d3LmViaXoucG9saWNlLm5zdy5nb3YuYXUlMkZtZWRpYSUyRjIwMjEwLmh0bWwmYWxsPTE%3D>

New South Wales Police Force (2014) Public Affairs and Corporate Communications, 13 January 2014 <http://www.police.nsw.gov.au/about_us/structure/specialist_operations/public_affairs_branch>

Newburn T (2001) ‘The Commodification of Policing: Security Networks in the Late Modern City’, Urban Studies 38(5–6), 829–48

Newman N, Dutton WH and Blank G (2011) ‘Social Media in the Changing Ecology of News Production and Consumption: The Case in Britain’, Oxford Internet Institute Working Paper, Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism Working Paper <http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1826647>

Phillips N and Hardy C (2002) Discourse Analysis: Investigating Processes of Social Construction, Sage

Potter GW and Kappeler VE (2006) Constructing Crime: Perspectives on Making News and Social Problems, Waveland Press

Poynting S and Morgan G (eds) (2007) Outrageous: Moral Panics in Australia, ACYS

Prenzler T, Sarre R and Earle K (2007/8) ‘Developments in the Australian Private Security Industry’, Flinders Journal of Law Reform 10, 403–17

Quilter J (2014) ‘Populism and Criminal Justice Policy: An Australian Case Study of Non-punitive Responses to Alcohol-related Violence’, Australia and New Zealand Journal of Criminology 0(0),

1–29

Reiner R (1997) ‘Media Made Criminality’ in M Maguire, R Morgan and R Reiner (eds), The Oxford Handbook of Criminology, Oxford University Press, 189–231

Reiner R, Livingstone S and Allen J (2000) ‘No More Happy Endings? The Media and Popular Concern about Crime since the Second World War’ in T Hope and R Sparks (eds), Crime, Risk and Insecurity, Routledge

Richardson JE (2007) Analysing Newspapers: An Approach from Critical Discourse Analysis, Palgrave MacMillan

Riffe D, Lacy S and Fico FG (2008) Analyzing Media Messages: Using Quantitative Content Analysis in Research, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc

Rigakos G (2008) Nightclub: Bouncers, Risk, and the Spectacle of Consumption, McGill-Queen’s University Press

Rowe D, Stevenson D, Tomsen S, Bavinton N and Brass K (2008) ‘The City After Dark: Cultural Planning and Governance of the Night-time Economy in Parramatta’, Centre for Cultural Research, University of Western Sydney

Sarre R and Prenzler T (2011) ‘Private Security and Public Interest: Exploring Private Security Trends and Directions for Reform in the New Era of Plural Policing’, Final Report, Australian Research Council

Smith SJ (1984) ‘Crime in the News’, British Journal of Criminology 24(3), 289–95

Tomsen S (2005) ‘Boozers and Bouncers: Masculine Conflict, Disengagement and the Contemporary Governance of Drinking-related Violence and Disorder’, Australian and New Zealand Journal of Criminology 38(3), 283–97

Tomsen S and Wadds P (2015) ‘Masculine Violence, Nightlife and Policing’ in J Stubbs and S Tomsen (eds), Australian Violence, Federation Press

Uribe R and Gunter B (2004) ‘Research Note: The Tabloidization of British Tabloids’, European Journal of Communication 19(3), 387–402

Uribe R and Gunter B (2007) ‘Are “Sensational” News Stories More Likely to Trigger Viewers’ Emotions than Non-Sensational News Stories? A Content Analysis of British TV News’, European Journal of Communication 22(2), 207–28

Wadds P (2011) ‘Securing Nightlife: Media Representations of Public and Private Policing’, Paper presented at The Australian and New Zealand Critical Criminology Conference 2010, Sydney Law School, University of Sydney

Wadds P (2013) Policing Nightlife: The Representation and Transformation of Security in Sydney’s Night-Time Economy, PhD Thesis, The University of Western Sydney

Walker F (1999) ‘Thugs Lay it on the Line: Train Security is Being Fast-tracked and Night Travellers Know Why’, The Sun Herald (Sydney), 8 August 1999, 15

Weatherburn D (2011) ‘Uses and Abuses of Crime Statistics’, Contemporary Issues and Crime and Justice No 153, NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research

Weber S (2012) ‘Time to Call Time on Boozy Violence’, The Daily Telegraph (Sydney), 12 July 2012, 24

Welch D (2008a) ‘Police Chiefs Call for War on Drunks’, The Sydney Morning Herald (Sydney), 8 May 2008, 3

Welch D (2008b) ‘Police Get Tough on Alcohol’, The Sydney Morning Herald (Sydney), 4 October 2008, 8

Williams P and Dickinson J (1993) ‘Fear of Crime: Read All About It? The Relationship between Newspaper Crime Reporting and Fear of Crime’, British Journal of Criminology 33(1), 33–56

Winlow S (2001) Badfellas: Crime, Tradition and New Masculinities, Berg

[*] Lecturer in Criminology, School of Social Sciences and Psychology, University of Western Sydney, Locked Bag 1797 Penrith NSW 2751 Australia. Email: p.wadds@uws.edu.au.

[†] These search terms were selected to ensure maximum coverage on content relevant to this study. The term ‘pubs’ was preferred to ‘licensed venues’, ‘bars’ and ‘clubs’ as it was more frequently used in the two selected newspapers. The use of the search terms ‘police and alcohol’ was used to ensure that the collected content was not specifically focused on licensed premises, but also featured the policing of nightlife spaces more broadly. All the collected articles were subjected to basic coding and sorted into themes that reflected the media depiction.

[‡] The ‘special constable’ refers to a government sanctioned officer who is employed to satisfy demand for security in times of emergency. Dating back over a century, the last time special constables were employed in Sydney was when a 10 000-strong riot threatened Circular Quay in the early 1900s (Lamont 1999).

[§] This conscious effort by the NSW Police to reinforce its public image and be seen as being ‘in control’ comes in the wake of significant public embarrassment surrounding a reported increase in numbers of ‘drive-by’ shootings and gun-related violence in Sydney (BOCSAR 2012). While these crimes are not necessarily recognised or debated as a form of after-dark violence, they are overwhelmingly forms of crime that occur at night, and their occurrence quite possibly reinforces a greater level of communal fear regarding night-time crime.

[**] Major legislative and regulatory amendments in other jurisdictions include: Security and Related Activities (Control) Amendment Act 2007 (WA); Security Providers (Crowd Controller Code of Practice) Regulation 2008 (Qld); Security Providers (Security Officer Licensed Premises Code of Practice) Regulation 2008 (Qld); Security Providers Regulation 2008 (Qld); and Security and Investigations Agents Regulations 2005 (Tas).

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/CICrimJust/2015/13.html